Visions of the Beginning and End: From Bruegel’s War in Heaven to the Bamberg Apocalypse

Another spooky post for the Eve of All Hallows

We might be more aware now, in the midst of what looks like a collapse of the modern industrialised civilisational proposal, that chaos is something always lurking behind a corner, waiting to pounce on mankind. The fragility of human achievements, the thin veneer of order separating society from upheaval, is an idea that has haunted humanity for centuries. Artists and writers have grappled with the spectre of this potential for anarchy, not just as a threat to daily life but as a spiritual and cosmic force; we fear a fundamental disorder at the heart of the created world opposed to divine creation and harmony.

This fear of and fascination with chaos find powerful expression in the apocalyptic art of the middle ages. In the bizarre and abstracted grotesqueries of painters like Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel the Elder we are confronted by this lurking disorder in ways that capture the darker corners of the human imagination and expresses the anxieties of their age and ours. Our continued fascination with Bosch’s surreal visions of hell and Bruegel’s grotesquely distorted chimeras of fallen angels show how deeply embedded this theme is in the collective psyche.

Their works remind us of the eternal struggle between order and chaos; not just a material battle to build sound flourishing societies, but an ancient spiritual and existential war in heaven, resonating deeply in periods of upheaval and uncertainty. It cuts to the core of our struggle; this is why our societies fail, why every civilisation descends into collapse eventually.

In today’s post for all subscribers for the Vigil of the Feast of All Saints, we’ll look at two great works of medieval art, the chaotic, strange and enigmatic painting, The Fall of the Rebel Angels, by Pieter Bruegel the Elder and one very early illuminated manuscript of the Book of Revelations, the Bamberg Apocalypse.

First, we turn to the unsettling and enigmatic The Fall of the Rebel Angels that channels the medieval fascination with the great cosmic battle between God’s order and Satan’s disorder, presenting a visual discordant cacophony of grotesquely distorted and fragmented forms that describe the fundamental wrongness of evil as a contradiction and denial of the order of the created universe.

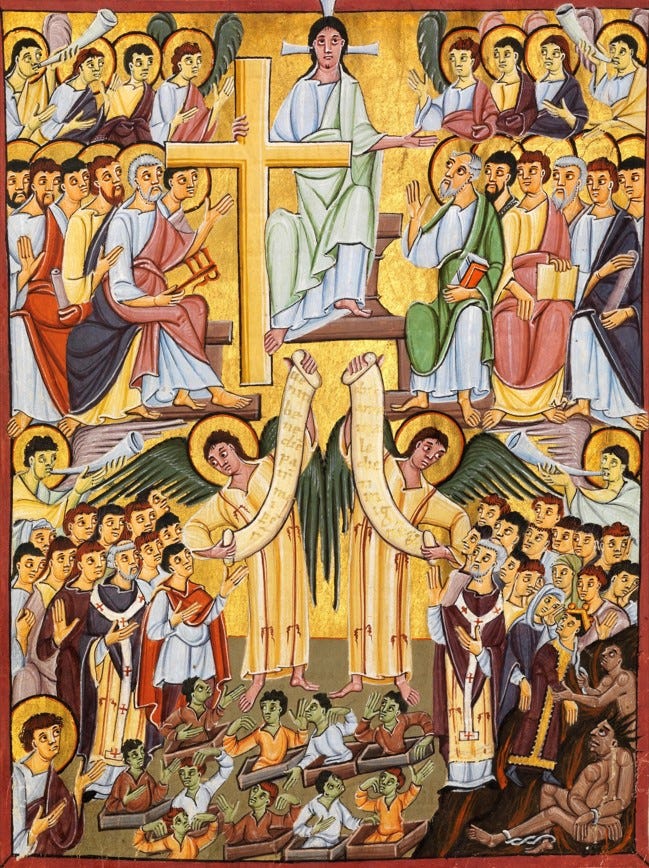

Contrasted with this vision of anti-order, the vivid and almost stark illuminations of the Bamberg Apocalypse, a masterpiece dating to the early 11th century, bring into sharply focused clarity the apocalyptic visions of St. John. These are images of deeply layered symbolism a profound description of God’s radical restoration of the cosmic order, broken first by Lucifer’s rebellion, and then by Adam’s fall.

By placing these works side by side, we can see how Christian art through the centuries has grappled with the profound themes of loss, evil, sin, judgment, restoration and the cosmic struggle between chaos and order, sin and redemption. These images offer a powerful contemplation for the Vigil of All Saints, inviting us to consider the ultimate promise of God’s restoration of creation.

The Sacred Images Project is a reader-supported publication where we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. It’s my full time job, but it’s still not bringing a full time income, so I can’t yet provide all the things I want to and am planning for. You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week.

For $9/month you also get the second half of the weekly Goodie Bag post, plus a weekly paywalled in-depth article on this great sacred patrimony, plus our Benedictine Book Club in the Substack Chat. There are also occasional extras like downloadable exclusive high resolution printable images, ebooks, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts.

If you would prefer to set up a monthly recurring donation in an amount of your choice, or make a one-off contribution, you can do that at my studio blog. Of course, anyone setting up a monthly patronage for US $9/month or more will get a complimentary subscription to the paid section here.

This helps me a lot because the patronages through the studio blog are not subject to the 10% Substack fee:

This is the site where I post photos of my own work as it develops. I have a shop there where some of my drawings and paintings are available for sale as prints, as well as some other items.

I’m stocking the Christmas shop and am happy to have found this lovely painting the other day by an unknown painter of the late Italian Gothic. It’s available in the shop as a printed standing panel, and just today as a porcelain Christmas tree ornament.

Browse the shop for more Christmas treasure here:

What does evil look like? A cosmic and interior conflict

For what I am doing, I do not understand. For what I will to do, that I do not practice; but what I hate, that I do. If, then, I do what I will not to do, I agree with the law that it is good. But now, it is no longer I who do it, but sin that dwells in me. For I know that in me (that is, in my flesh) nothing good dwells; for to will is present with me, but how to perform what is good I do not find. For the good that I will to do, I do not do; but the evil I will not to do, that I practice.

Romans 7:15-19

Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s The Fall of the Rebel Angels is a work of profound visual and symbolic complexity. It visually captures the discordant nature of evil in a way that is at once literal, with its bizarre, anti-natural figures, and maddeningly, reality-defyingly complex. Bruegel brings both the inner, personal and external, cosmic spiritual conflict to life in a chaotic and nightmarish scene.

The scene is a disconcerting chaotic mass, with multiple layers of creatures that defy gravity, upness and downness, and all taxonomic categorisation or reason, each one an unholy amalgamation of animal, insect, and human parts, reflecting the spiritual and moral chaos and anti-rationality of Lucifer’s followers.

The complexity draws the viewer in to try to make sense of it. And as we are drawn into the painting’s frenetic energy, we are forced to confront the uneasy reality that this cosmic battle between order and disorder is also an illustration of our own internal struggle, the human experience of temptation and the agony of moral conflict.

At first glance, the painting’s sheer tumult is overwhelming, a deliberate strategy that pulls the viewer into the frenzied struggle where divine and demonic forces - these grotesquely distorted and fragmented forms - collide. These creatures, neither wholly human nor entirely animal, evoke a sense of profound unease - in many cases their parts don’t fit to create a comprehensible whole - tails where heads should be - an apt visual description of interior moral conflict.

Their anatomically impossible and unnervingly hybrid shapes seem to writhe and twist in a discordant cacophony, that describes more than just physical deformity; they symbolise a deeper spiritual perversion - the anti-real, the anti-natural. Evil, in Bruegel’s vision, is not merely the absence of good but an active and force of chaos and anti-rationality, a willed denial of the harmonious order that God instilled in creation.

No quarter for or negotiation with evil: “What concord hath Christ with Belial?”

The angels, led by Archangel Michael, are an absolute contrast, serene and even smiling in the midst of all this, yet resolute and indomitable.

In their beauty and simplicity their forms are idealised and glowing with a sense of purity and purpose - the utter vanquishing of evil.

Clad in shimmering armour, laying about with sharp swords, and surrounded by an aura of light, they embody the celestial order and the unwavering strength of God’s will.

This stark opposition between the angelic hosts and the hellish abominations not only heightens the drama of the scene but also underscores the spiritual and moral gulf between the forces of good and evil.

The Bamberg Apocalypse: Illuminated Visions of Revelation

Created in the early 11th century, the illuminations of the Bamberg Apocalypse use a precise, simple and deliberate style to communicate the unshakeable order of God’s divine plan. The figures of angels and saints are rendered with an almost crystalline clarity, surrounded by radiant gold backgrounds that symbolise heavenly light and incorruptible eternal holiness.

This scene of divine order sharply contrasts with the grotesque, writhing chaos found in Bruegel’s The Fall of the Rebel Angels. At the top of the composition sits Christ enthroned, serene and authoritative, surrounded by the heavenly host of Angels, Apostles and saints. The figures are symmetrical, monumental organised in classically ideal proportions, emanating a sense of stability and divine justice. The golden background is a symbol of divine light, enveloping the entire heavenly scene in an otherworldly glow; Christ’s judgment is beyond earthly corruption and beyond all negotiation, eternally radiant and just.

Two angels hold a long scroll, the Book of Life, with the saved gathered on the right and the damned on the left. The saved are depicted with calm, composed postures, signifying their perfected natures, whole and at peace interiorly. The damned figures are turned away from the divine vision, and expressions of anguish are a subtle nod to the chaos of evil, but even here, the composition remains controlled and measured, reinforcing the ultimate supremacy of divine order over sin and disorder.

Symbolism and Theological Implications

The Bamberg Apocalypse uses this visual order to communicate theological truths: God’s plan is clear, purposeful, and unshakeable, unavoidable. The angels and saints form a harmonious celestial assembly. In this illumination, even the representation of the damned adheres to a precise visual hierarchy; God’s justice imposes order, even in judgment.

The stark clarity and divine light of the Bamberg Apocalypse provide a visual reassurance that, despite the ever-present threat of spiritual disorder, God’s order and justice are eternal.

Each scene is meticulously composed, evoking a sense of stability and spiritual assurance, even in the face of apocalyptic events. Unlike Bruegel’s writhing, grotesque demons, the Bamberg Apocalypse depicts the forces of evil in forms that are stark but controlled, serving as reminders of God’s ultimate authority over chaos. This clear, ordered imagery reflects a worldview where the triumph of divine justice is not questioned but proclaimed with unwavering conviction, offering a vision of hope and divine restoration amid the darkness of Revelation’s prophecies.

The full manuscript has been digitised and can be viewed here.

Diverging Theological Emphases

The contrast between the Bamberg Apocalypse and Bruegel’s War in Heaven reflects broader shifts in Christian theological perspectives over the centuries. The Bamberg Apocalypse situates the struggle in a cosmic order, portraying heaven’s armies as idealised, divine forces separated from earthly concerns. Its illuminations are intended to evoke awe, reminding the viewer of the grandeur and mystery of divine justice, with an emphasis on the ultimate triumph of good.

Bruegel’s work reflects a post-medieval world, entering the “early modern” period, preoccupied with human fallibility and the often violent conflict between spiritual and temporal power. His war in heaven brings the Apocalypse down to earth, depicting the battle not as a purely supernatural event but as something that touches upon humanity’s own struggles with pride, rebellion, and redemption. In an era marked by political strife and religious upheaval, Bruegel’s painting might be read as a meditation on the power of sin and the human need for divine grace.

What a post for All Hallows Eve! The Bruegel painting is amazing - and the explanation about the glow answered some questions for me. He had real artistic command and what he did was "beautiful" except for the hellish creatures. The huge question for me remains: How in the world did Bruegel sit with this painting and survive over the time he painted it? Did he sleep at night? I mean, it had to be created in his head (like the worst nightmares) and put onto whatever medium he used. I would be so depressed and scared of what I created. Do we know much about Bruegel himself? But I do appreciate what he did. It just shows the terrors of hell and that probably put a lot of fear of God in the minds of those who saw this painting!

I love Bruegel, have admired his paintings countless times. This is a very cool thing to know: "The glow comes from a very specific painterly technique: the whole painting starts with a warm yellow ochre underpainting, even under the blue sky."