Thy word is a lamp to my feet, and a light to my path.

(Psalm 119:105)

The early Christian desert was not empty. It was full of angels, demons, silence, and God - and hermit monks. Those who fled the noise of cities and the tumult of crowds sought not escape, but to wrestle against the Self and the demons with the power of the Word. The earliest monks, most of whom left no writings, became instead witnesses through the lives they lived and the images they inspired.

In the earliest days of monasticism, after the Roman persecutions had ceased, some Christian souls were stirred to seek what came to be called “white martyrdom,” a voluntary death to the world, pursued through solitude, ascetic labour, and unceasing prayer. In these earliest times, there were no written rules to follow, no orders to join and permission was not needed from any ecclesiastic in Rome or Constantinople. You simply decided to do it.

Lo, I have fled far away and dwelt in the wilderness. I waited for Him that saveth me from faintheartedness and tempest.

(Psalm 55:6–8)

In today’s post for all subscribers, we look at the beginnings of Egyptian monasticism, before the Rule of St. Benedict, before the great monasteries, before there were even formal communities to join. These were the days of caves, cells, and tombs on the edge of the desert, where the first Christian hermits sought a deeper union with God through solitude, fasting, prayer, and the recitation of the Psalms. We explore the early monastic settlements, the daily routines of the Desert Fathers, their spiritual struggles with the logismoi, and the path that led them not away from the world, but into a different kind of communion. From the monastic settlements of Egypt, this is a look at how silence became image, and prayer became flame.

At the Sacred Images Project we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. The publication is supported by subscriptions, so apart from plugging my shop, there is no advertising or pop-ups. It’s my full time job, and while it’s now providing me with a full time income, we are now looking at growing this into a multi-layered, multi-media project, so I can’t yet provide all the things I want to and am planning for.

You can subscribe for free to get one a week.

For $9/month you also get a second, weekly in-depth article tracing the history and meaning of our great sacred patrimony. For paid subscribers there are also extra posts with in-person explorations, exclusive photos and videos and materials like downloadable exclusive high resolution printable images. In the works are ebooks, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts.

More about the life of St. Anthony here:

Drawn by a hunger for intimacy with God, these first solitaries retreated into the deserts, mountains, caves and tombs outside the cities. Often they would find a hermit already living the life, and settle nearby, not to be taught in the modern sense, but to watch, to pray with and to imitate, to grow silently under the patient guidance of a more advanced soul.

The visual language that formed around early Christian eremitical desert solitude is tranquil but vivid. In wall paintings recovered from the remains of the monastery of Bawit, we see serene faces with wide, watching eyes.

What was this strange life?

The Desert Fathers were a diverse group of men (and women) who retreated from the structures of late Roman urban society beginning in the late third and early fourth centuries. Though they are often treated as a single movement, in reality they represented a variety of approaches to solitude, prayer, and ascetic life. Some lived alone in caves or abandoned tombs; others gathered into loose clusters of cells in remote areas, forming the earliest monastic communities. What united them was a deep, irresistible desire for intimate, un-distracted unity with God in intense prayer.

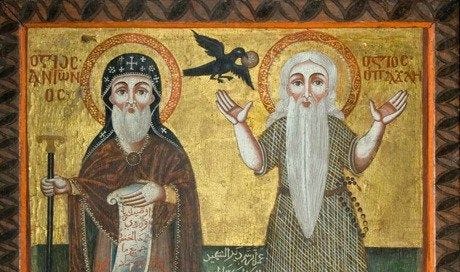

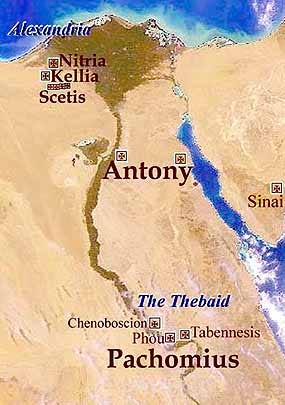

The first known desert hermit was St. Paul of Thebes, who fled to the Theban desert during the Decian persecution (249–251). Tradition holds that he was buried by his more famous disciple, St. Anthony the Great, the “father of all monks.” St. Anthony himself was to acquire disciples who would found the larger monastic communities.

These loose clusters of cells, gathered around a more experienced spiritual guide, is known to this day as a “laura” or “lavra,” from the Greek, meaning a narrow path or alley. In Egypt these cells would be caves or stone huts each housing a single monk, but connected by a trail. As a rule they were close enough together to be within earshot of a shout for assistance should the need arise. A central church would be near by for common liturgical services, often as well as rudimentary guest accommodation. Like the later Carthusians, the monks would work, pray, eat and sleep in their cells, but came together for certain regular liturgical or communal functions.

The laura of hermits, a semi-eremitic or semi-anchoritic model, a middle ground between total solitude and full communal (cenobitic) life, was the standard for monastic life for a very long time, and is still found in the Christian East. This form became especially influential in Egypt, Palestine and Syria in the 4th–6th centuries, and it was in this form that monasticism was first introduced into what would become Western Europe.

Among the most important figures were St. Anthony the Great (c. 251–356), regarded as the founder of Christian eremitic monasticism, and St. Pachomius (c. 292–348), who established the first structured cenobitic communities in Egypt. Their followers included Macarius of Egypt, Arsenius the Great and a number of lesser-known but deeply influential spiritual elders. The teachings and sayings of many of these figures were preserved in collections like the Apophthegmata Patrum (Sayings of the Desert Fathers), a patchwork of brief, powerful stories that shaped Eastern Christian spirituality for centuries.

"Lo, I have fled far away and dwelt in the wilderness. I waited for Him that saveth me from faintheartedness and tempest."

(Psalm 55:6–8)

The Combat of the Desert - becoming all flame

This is not escapism. It is spiritual warfare. The stylite, a madman by our standards, dwells on a pillar to wrestle with the devil and with his own thoughts. The anchorite’s body withers, but the eyes of his soul grow bright. And finally a hermit can become “all flame” - an expression the monastic sources certainly meant literally:

Abba Lot came to Abba Joseph and said, “Abba, as far as I can I say my little office, I fast a little, I pray and meditate, I live in peace, and as far as I can I purify my thoughts. What else can I do?”

Then the old man stood up and stretched his hands toward heaven. His fingers became like ten lamps of fire and he said: “If you will, you can become all flame.”

Though their outward lives seemed harsh and strange, the goal was never mere self-denial. The aim was purity of heart, a state in which prayer became a constantly lived state, the passions were stilled, and the presence of God could be perceived directly. Their solitude was not an escape from others, but a way of loving more perfectly.

This idea of the ascetic, monastic life as a great combat with evil, is often lost in popular depictions, which either romanticise it as a peaceful, worry-free escape from the world or dismiss it as a passive, unproductive withdrawal. But to the early monks, nothing could be more active or dangerous than entering the great desert silence. In the city, one could remain distracted. In the desert, one’s own heart cried out in the stillness.

The phrase “the combat of the desert” refers to the intense spiritual struggle that the Desert Fathers and Mothers voluntarily undertook. Their solitude was not a retreat from conflict, but the very battleground on which they confronted the deepest enemies of the soul: pride, anger, lust, despair, spiritual delusion, and above all, the logismoi, the ceaseless flow of distracting and disordered thoughts. Cut off from worldly distraction, they met these forces head-on. The desert, stark and silent, offered no place to hide from the self.

In that exposed space, they turned to the scriptures, especially the Psalms, unceasing prayer, and manual labour as weapons in the daily fight for purity of heart. In the earliest phase of the desert movement, prayer was primarily individual, personal with the goal of having it be “unceasing,” the recitation of Psalms, short memorised scriptural verses and spontaneous mental prayer woven into manual labour, all couched in silence.

But by the 5th and 6th centuries, especially in larger, more stable settlements like Nitria and Kellia, we begin to see the emergence of a more regular daily schedule. Written sources and archaeological evidence suggest a rhythm that included set hours of prayer, most notably Vespers in the evening either alone or with a neighbouring monk, periods of rest and work, and a central weekly synaxis for liturgy, comunity and instruction. Psalms continued to form the backbone of prayer, with some monks memorising all 150 and reciting them over the course of the week or more often.

In addition to psalmody, they engaged in manual labour, fasting, vigil at night, and long periods of silent meditation. The goal was not just to say prayers, but to become prayer, to enter into an ongoing state of watchfulness (nepsis), in which the monk remained present to God at every conscious moment.

It was there, precisely in the absence of noise and comfort, that the demons came, not always in visible forms, but according to all the records, as inner torments, temptations, and illusions. The Desert Fathers were clear-eyed about this. Their goal was not comfort, but transformation: to let the ego die, to be burned clean by divine fire.

Beware the Logismoi

The eight logismoi are the eight fundamental thoughts or temptations that the Desert Fathers, particularly Evagrius Ponticus (c. 345–399), identified as the root causes of all sinful behaviour and spiritual unrest. They are not sins themselves but disordered inner impulses, obsessive or recurring, habitual thoughts or temptations, that must be recognised, confronted, and purified.

Later, these were condensed and adapted by St. John Cassian and eventually became the Seven Deadly Sins in Western tradition, with vainglory folded into pride, and sadness and acedia merged into sloth.

Here they are:

Gluttony (gastrimargia): Obsession with food and physical pleasures; not just overeating but disordered attachment to comfort, timing, or quantity.

Lust (porneia): Sexual temptation in thought or fantasy; disordered desire for physical intimacy.

Avarice (Greed) (philargyria): Anxiety about material possessions; the hoarding impulse; fear of not having enough.

Anger (orge): Resentment, rage, inner indignation; a refusal to let go of perceived wrongs.

Sadness (Despondency) (lypē): Spiritual sorrow that drags the soul down; distinct from holy grief or repentance. This is often linked with regret, self-pity, or paralysis of the will.

Acedia (Sloth or Listlessness) (akēdia): Apathy, boredom, or spiritual torpor; a kind of restlessness or disgust with spiritual effort. Often called “the noonday demon.”

Vainglory (kenodoxia): Desire for praise, attention, or reputation; performing good actions to be seen.

Pride (hyperēphania): The root of all others: an inflated self-image, contempt for others, and resistance to grace.

Apophthegmata - wise sayings

A few samples of the stories of wisdom from the ancient desert monks.

~

One of the fathers told a story of an elder at Kellia, of extremely ascetic habit, whose clothing was a mat. He went to Abba Ammon and as the latter saw that this garment was matting and said to him: “This is of no use to you at all.” He then asked him: “Three thoughts disturb me: going into the desert, going to a foreign country or locking myself in a cell, not seeing anyone and eating only every two days.” Ammon replied: “You may do none of these. Go back to your cell and eat a little each day. And keep the words of the tax collector in mind: ‘Have mercy on me, for I am a sinner,’ and you will be saved.”

~

Abba Ammon was asked, “What is the ‘narrow and hard way?’” He replied, “The ‘narrow and hard way’ is this, to control your thoughts, and to strip yourself of your own will, for the sake of God. This is also the meaning of the sentence, ‘Lo, we have left everything and followed you.’”

~

Abba Ammon one day went to visit Abba Anthony and lost his way. He sat down for some time and fell asleep. When he woke up, he arose and prayed to God: “My Lord, do not, I beg you, allow your creature to die.” He lifted up his eyes and saw something like a human hand hanging over him and pointing the way until he arrived and stood over the cave of Anthony.

~

Abba Anthony once went to visit Abba Ammon in Mount Nitria and when they met, Abba Ammon said, ‘By your prayers, the number of the brethren increases, and some of them want to build more cells where they may live in peace. How far away from here do you think we should build the cells?’ Abba Anthony said, ‘Let us eat at the ninth hour and then let us go out for a walk in the desert and explore the country.’ So they went out into the desert and they walked until sunset and then Abba Anthony said, ‘Let us pray and plant the cross here, so that those who wish to do so may build here. Then when those who remain there want to visit those who have come here, they can take a little food at the ninth hour and then come. If they do this, they will be able to keep in touch with each other without distraction of mind.’

The earliest days - Nitria and Kellia

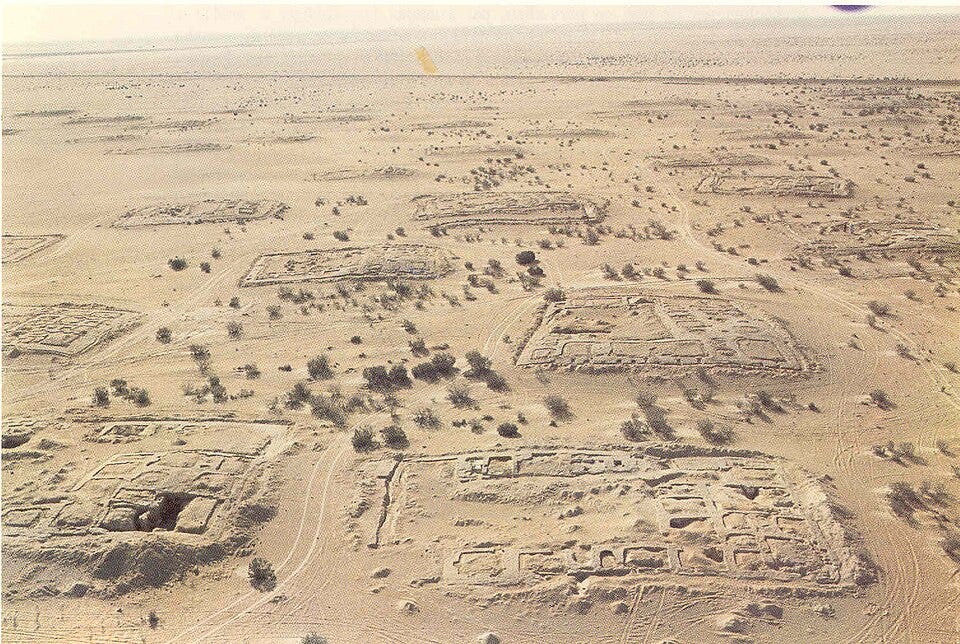

The earliest monastic settlements in Egypt were often extremely simple: scattered huts, caves, or repurposed tombs in the desert, loosely connected by narrow footpaths. Over time, some of these clusters developed more structure, forming permanent lauras with chapels, guesthouses, and cisterns. In a few cases, such as Nitria, Scetis, and Kellia, archaeological remains show large, solidly established communities with organised communal planning; buildings, painted chapels, and even rudimentary libraries. These early desert settlements were austere by design, but they eventually became spiritual centres that attracted pilgrims, copyists, and seekers.

Nitria is the earliest of the three major centres of Christian monastic activity in the Nitrian desert of the 4th century, the other two being Kellia and Scetis. Founded in 330 by St. Ammon, it quickly attracted thousands of monks and by 390 it had evolved from a loose collection of solitary monks to an enormous, busy and organised community with bankers, merchants and church services for the public. It was from here that Abba Ammon, after consulting with St. Anthony, removed with a group of advanced ascetics to Kellia.

It was believed in the 390s up to 600 monks were living the ascetic life at Kellia, founded as a place where those already well accustomed to the disciplined life could seek greater austerity. By the 6th century these again numbered in the thousands with over 1,500 hermitages that have been surveyed.

According to the Historia Monachorum in Aegypto by Flavius Rufinus who personally visited Kellia, the cells were arranged far enough apart that “no one can catch sight of another nor can a voice be heard.” They came together on Saturday and Sunday to share a meal together and celebrate the liturgy, some journeying 3 or 4 miles from their cell to the church. If a monk failed to appear they would know he was sick or had died and someone would bring food or help or collect the remains. Evagrius Ponticus was reported by Palladius in his Lausiac History to have retired to Kellia after spending two years in Nitria.

Decline began in the 7th and 8th centuries due to doctrinal disputes in the Coptic Church and under pressure from raids by nomadic tribesmen out of the Libyan desert. The site was abandoned in the 9th century.

Teaser: tomorrow, a visit to the Red Monastery

We’ll leave off here, with the first monks of Egypt scattered across the desert, praying in their cells, labouring in silence, and waging the great inner combat. Their lives were marked by simplicity, but also by an intensity that shows in the visual culture that slowly emerged around them.

In a short extra post tomorrow for paid subscribers, we’ll explore more deeply than we have so far the art of these early Coptic monastic communities, from the painted chapels of Bawit to the stunning frescoes of the Red Monastery, and consider how that visual language was to influence later developments in Rome and Constantinople.

Great post, I'm more and more drawn to the early church fathers, the psalms etc. I feel like in our time they are a sure value to fight against the world, the flesh and the Devil when there's so many errors spread all around!

Today I went back to Mother Cécile's book we had been reading together a few months back. As I was slowly going through the first chapter (such a great primer on the spiritual life, thanks again for the recommendation!) I stumbled there on that very same quotation from Psalm 119 which you put at the top of your essay (Thy word is a lamp to my feet, and a light to my path.) - it jumped at me as it were, and I used it for lectio Divina. Seeing the same inspired words here made me smile, as you can imagine...