A story of restoration: Pisa's lost treasures and recovered frescos

... and what they found underneath.

Given all the Bad that’s been going on in the Church, I thought we could do with a bit of uplift today, a story of recovery from disaster. Nearly everyone in the world has heard of the Leaning Tower of Pisa, but perhaps not so many know about the incredibly glorious cathedral it was built for, and the artistic treasures to be found there.

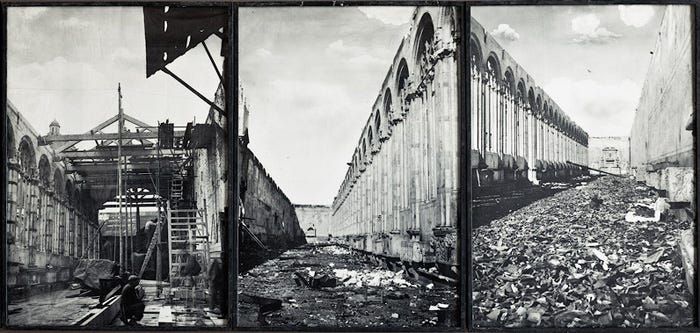

It’s also not widely known that this place, the Camposanto, was bombed in World War II. It looks irrecoverable, doesn’t it. But as the internet meme goes: you can just do things. You can decide not to let things fall apart, and pick up pieces and put them back together again. All it takes is work and the decision to do it.

We’re taking a break today from the Big Editorial Plan, to just take a stroll around the glorious Romanesque Duomo of Pisa and the Gothic Camposanto (“Holy Ground” cemetery), courtesy of a big parcel of excellent photos taken by a friend of mine who took his niece there to see it today. He was texting them to me to admire, and kindly agreed to let me share them here with all of you.

Everybody say, “Thank you, James.”

At the Sacred Images Project we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. The publication is supported by subscriptions, so apart from plugging my shop, there is no advertising or pop-ups. It’s my full time job, and while it’s now providing me with a full time income, we are now looking at growing this into a multi-layered, multi-media project, so I can’t yet provide all the things I want to and am planning for.

You can subscribe for free to get one a week.

For $9/month you also get a second, weekly paywalled in-depth article tracing the history and meaning of our great sacred patrimony. For paid subscribers there are also extra posts with in-person explorations, exclusive photos and videos and materials like downloadable exclusive high resolution printable images. In the works are ebooks, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts.

From the shop: since we’re going to be talking about the opening of the monastic tradition in Egypt soon, this might be a good time for a little print of St. Anthony of the Desert, the father of monks. This is a little egg tempera painting I did based on a 14th century fresco in one of Narni’s medieval churches. The original is sold, but you can have a high quality art print either on a wood panel, or museum quality paper.

I think it would make an elegant addition to a prayer corner or mantel.

You can order one, and browse around lots of other nice things, at the shop, here:

Pisa’s miraculous Gothic treasure house

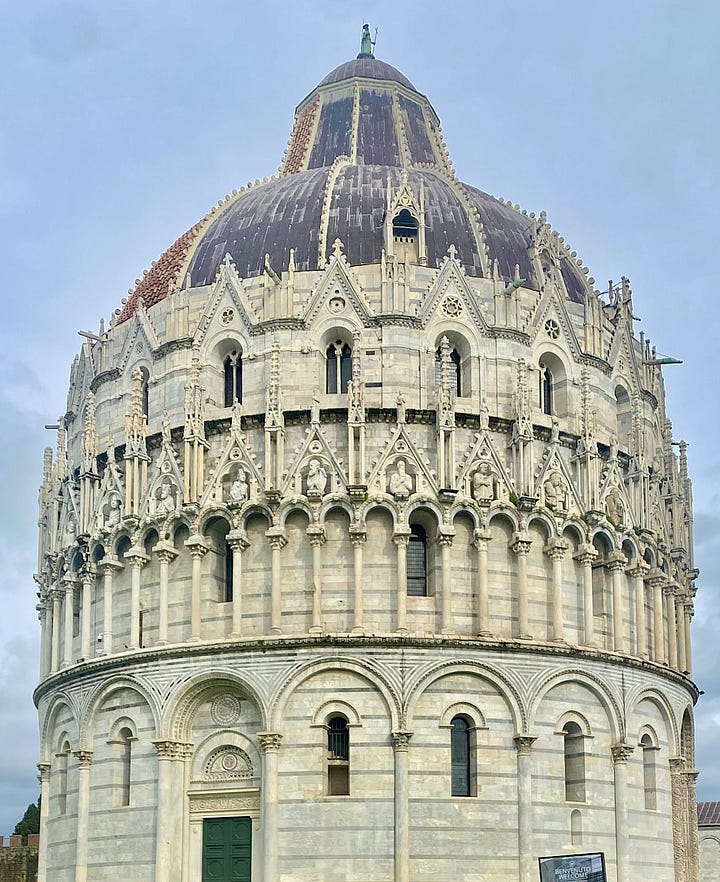

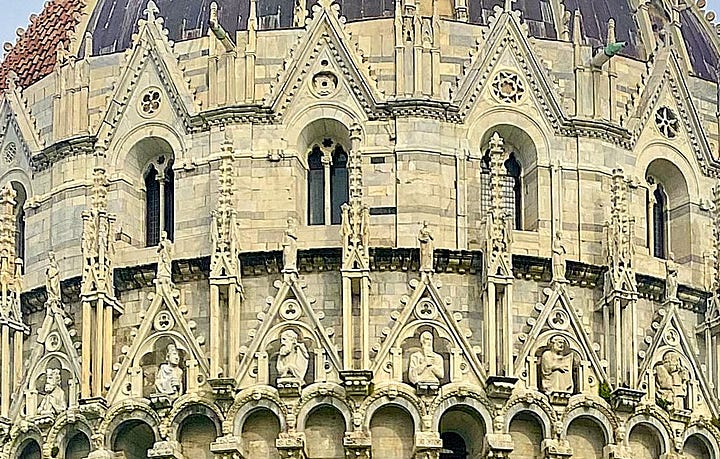

Pisa’s Piazza dei Miracoli (Square of Miracles) is one of the most remarkable architectural ensembles in Europe. It’s home to four extraordinary medieval structures, the Cathedral (Duomo), the Baptistery, the Leaning Tower, and the Camposanto Monumentale (constructed beginning in 1277), each a masterpiece in its own right. The complex reflects Pisa’s golden age as a powerful maritime republic, with its unique blend of Romanesque, Byzantine, and Islamic influences.

Duomo

At the heart of it all is the Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta, an 11th-century basilica that set the standard for the Pisan Romanesque style.

Its impressive marble façade, glittering mosaics, and richly decorated interior showcase the artistic ambitions of medieval Pisa.

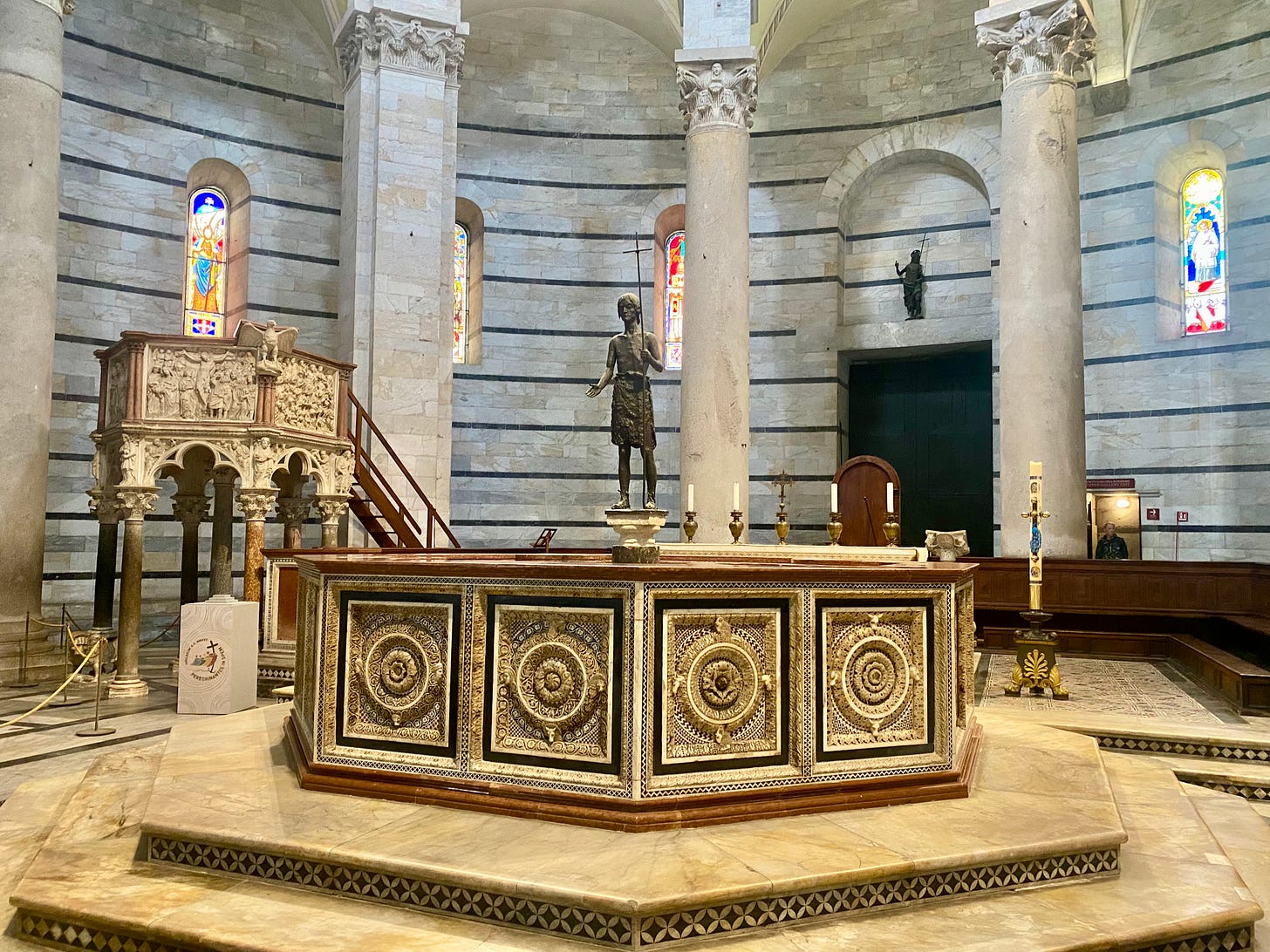

Baptistery

The Baptistery, the largest in Italy, is famous not only for its striking transition from Romanesque to Gothic architecture but also for its acoustics, which turn a single note into a symphonic echo.

Camposanto

Of course, the Leaning Tower of Pisa steals much of the attention. Originally designed as the cathedral’s bell tower, its unintended tilt, caused by unstable ground, made it an icon of architectural mishap and perseverance. The fact that it’s still standing, after centuries of engineering interventions, is almost as miraculous as its original construction.

The Camposanto Monumentale, however, holds a quieter, more haunting significance. This monumental cemetery, built in the 13th century, was once adorned with some of the most important frescoes of the medieval and early Renaissance periods.

Tragically, these artworks were heavily damaged during World War II. While much of Pisa’s monumental complex survived the war, the Camposanto’s frescoes were nearly lost forever. Their restoration is one of the great stories of post-war art conservation, a testament to the resilience of both the city and its cultural heritage.

During World War II, Pisa became a target of Allied bombing campaigns due to its strategic position along the Arno River. In 1943 and 1944, air raids devastated parts of the city, and one of the worst casualties was the Camposanto. Incendiary bombs struck the wooden roof, setting off a catastrophic fire that caused molten lead to drip onto the frescoes below, destroying much of the painted surface. These frescoes, some dating to the 14th century, had once been among the finest in Europe, illustrating biblical narratives, the Last Judgment, and complex theological themes.

The Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta also suffered damage, though not as extensively as the Camposanto. Sculptures, mosaics, and architectural elements were impacted, and urgent efforts were required to prevent further losses. Pisa’s medieval past was hanging by a thread, and saving what remained became an urgent post-war mission.

Bringing the Camposanto’s frescoes back to life

The restoration of the Camposanto frescoes was among the most complex conservation efforts in post-war Italy. The challenge wasn’t just in cleaning and stabilizing them, it was in deciding how to present their fragmented remains. Many frescoes were missing entire sections, and some had been reduced to little more than scattered pieces.

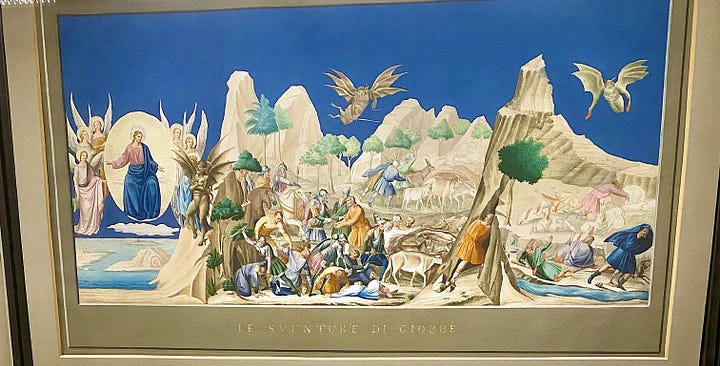

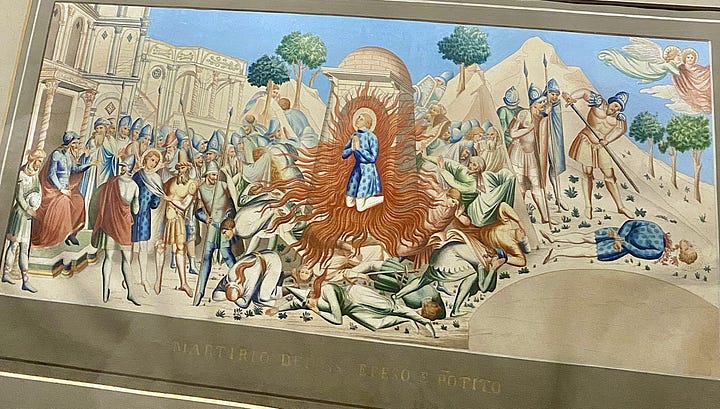

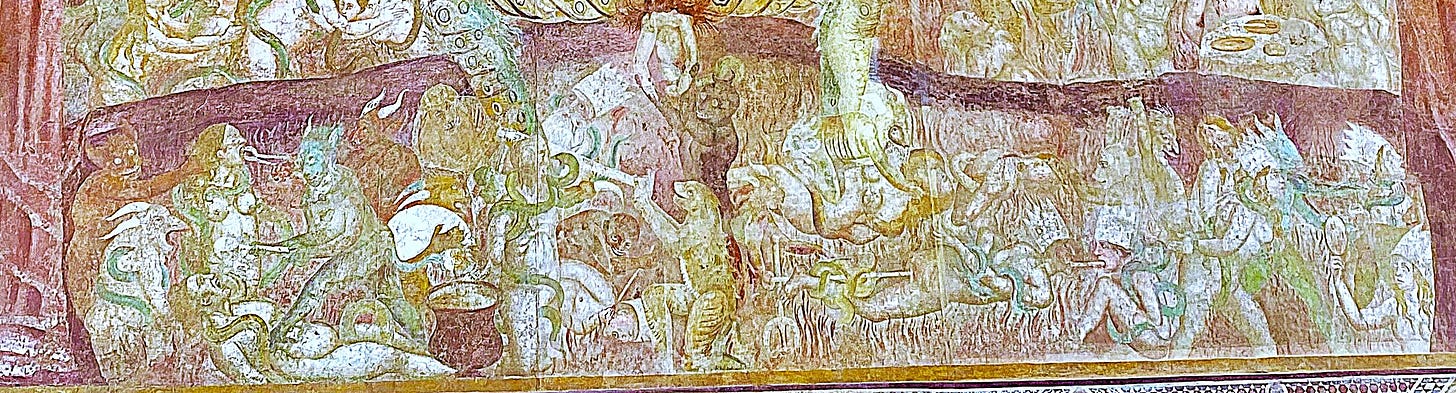

Among the most famous works was the Triumph of Death, attributed to Buonamico Buffalmacco, a stark and haunting vision of mortality. Another was The Last Judgment, a vivid depiction of heaven and hell.

Some had been reduced to fragments, while others had suffered severe charring. In the immediate aftermath of the war, preservation efforts focused on stabilizing what was left. Art historians and conservators, led by figures like the great art historian Deoclecio Redig de Campos, began the painstaking process of salvaging and preserving what remained.

The technique known as strappo (literally “tearing off”) was used to detach surviving layers of paint from the walls. This delicate process involved carefully peeling frescoes away from their original surfaces and mounting them onto new supports to prevent further degradation.

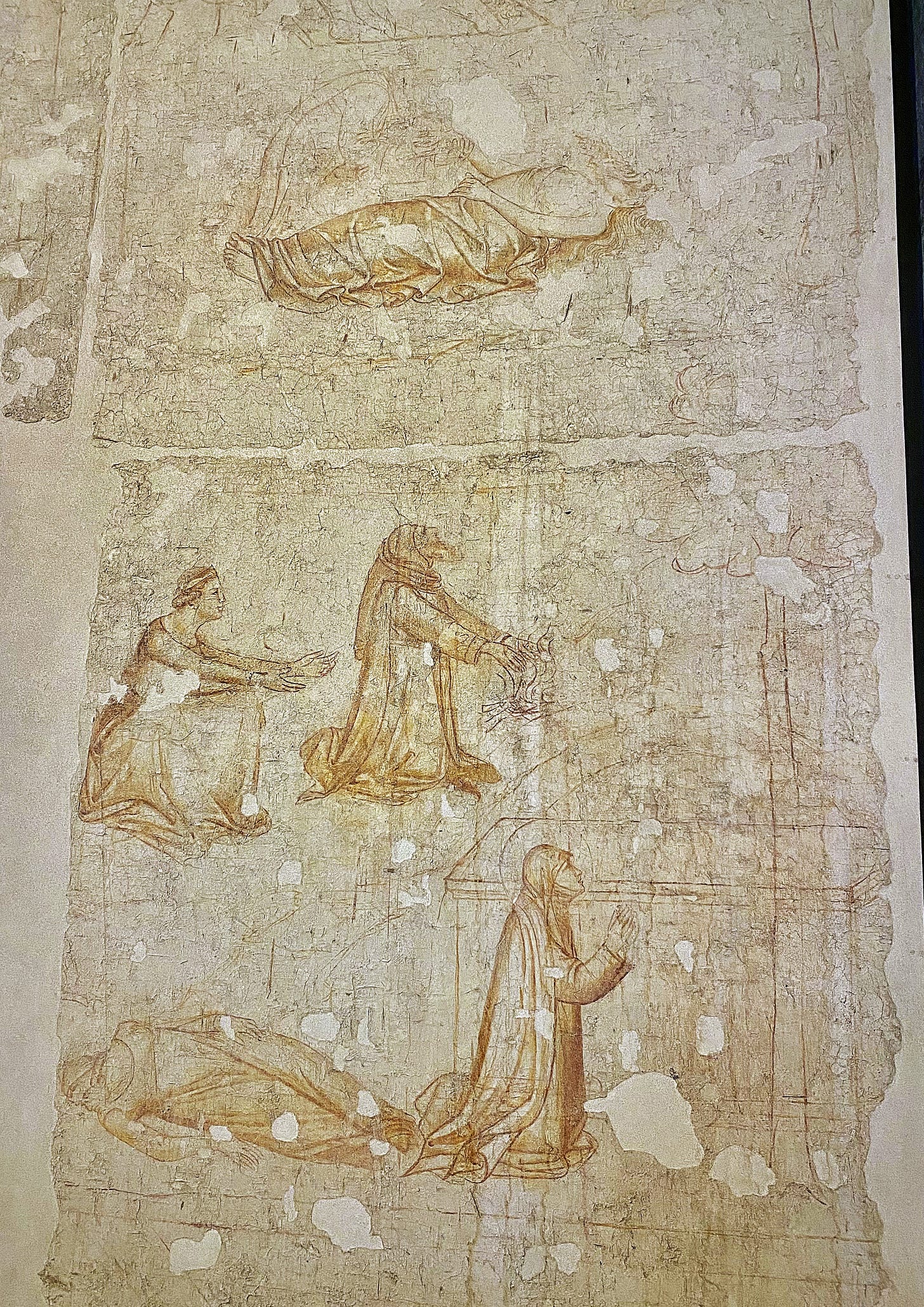

The discovery of forgotten treasures - the long lost drawings

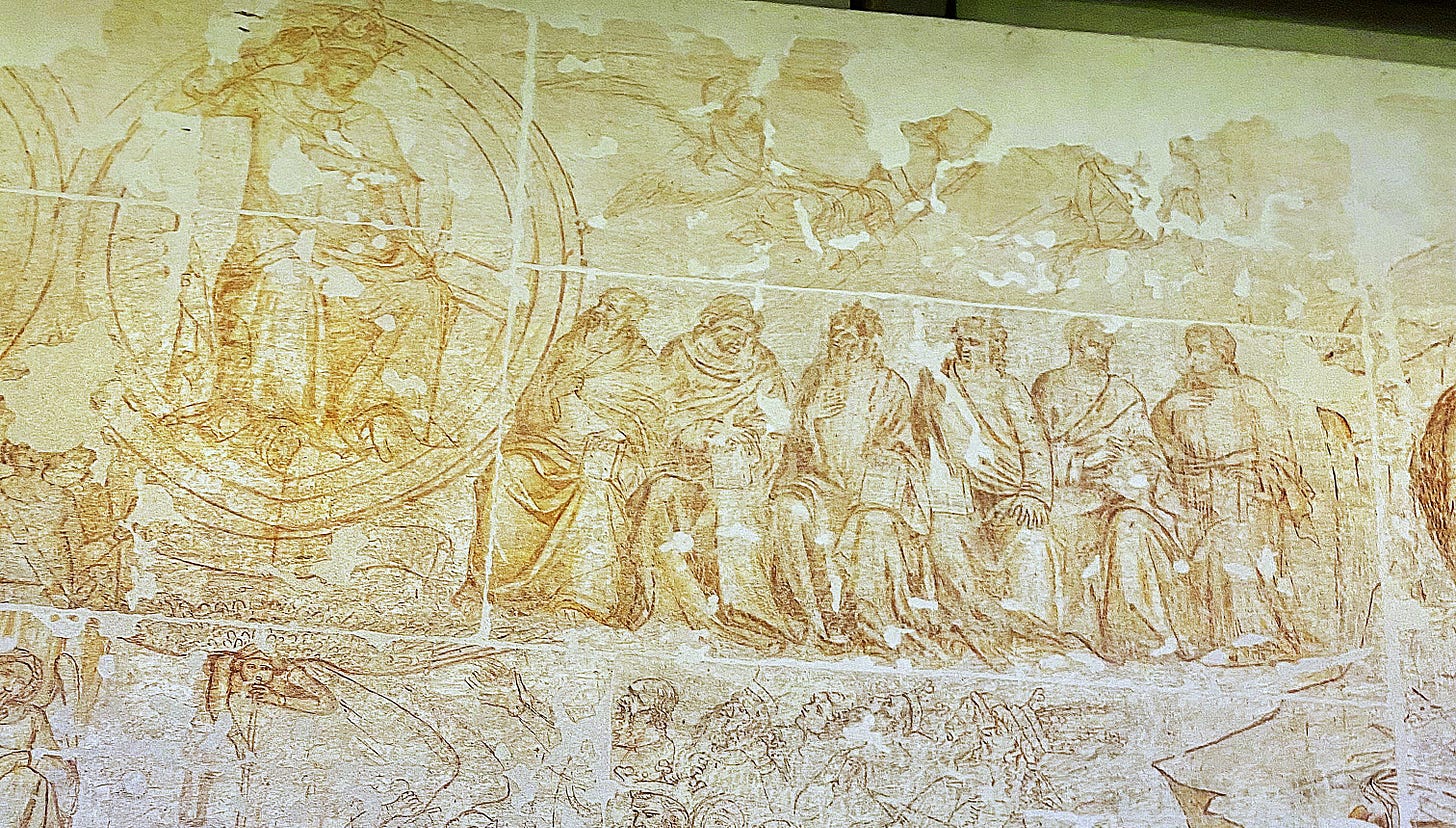

One of the most unexpected discoveries during the restoration of the Camposanto frescoes was the sinopie, or preparatory drawings, hidden beneath the painted layers. These underdrawings, sketched directly onto the wall before the frescoes were applied, revealed the raw artistic process of the medieval masters, something that had been invisible before the war.

As restorers used the strappo technique to remove the fresco fragments for preservation, they found that, in many cases, the original sketches remained intact on the wall. These sinopie were never meant to be seen by the public; they were rough, expressive outlines that guided the painters in their compositions. The lines were often more fluid and spontaneous than the final painted images, giving a rare glimpse into the artistic decisions and adjustments made along the way.

The discovery of these drawings was so significant that it led to the creation of the Museo delle Sinopie, a dedicated museum in Pisa where many of them are now displayed. There, visitors can see how artists like Buonamico Buffalmacco planned out complex scenes such as the Triumph of Death and The Last Judgment. In some cases, these preparatory sketches even included elements that were later modified or omitted in the final fresco, shedding light on the evolving vision of the painters.

These sinopie are more than just technical artifacts; they represent a bridge between the artist’s initial inspiration and the completed masterpiece. Their survival, an unexpected windfall after the wartime destruction, offers an extraordinary second layer of history, allowing us to appreciate not only the grandeur of the finished frescoes but also the creative process behind them.

The Theological Cosmography: mapping the medieval universe

One of the most intriguing frescoes in the Camposanto is the Theological Cosmography, by Pietro di Puccio in the late 14th century. This remarkable work presents a medieval vision of the universe, structured around a geocentric (Earth-centred) model that blends theology and pre-Copernican science.

At the centre of the fresco is a vast cosmic diagram held up by God the Father, depicted with Christ-like features. The concentric rings within the diagram represent different layers of existence. The outermost circles symbolize the nine Angelic Hierarchies, reflecting the celestial order described in Christian tradition. Moving inward, the three Heavens, Empyreal, Crystalline, and the Firmament, are depicted, with the Crystalline sphere marked by zodiac signs.

At the core of the fresco is Earth, shown with its three known continents, Europe, Asia, and Africa.

In the lower corners of the composition, two of the great medieval theologians, Saint Augustine and Saint Thomas Aquinas, appear with open books, reinforcing the idea that understanding the cosmos requires both divine revelation and intellectual inquiry.

This fresco is an extraordinary window into medieval thought, where faith and reason were not in conflict but part of a single quest for knowledge. Even in its damaged state, The Theological Cosmography remains one of the most fascinating representations of how people in the late Middle Ages understood the universe.

A legacy of survival

The scars of war remain visible in these masterpieces, serving as reminders of what was lost and what was saved. Today, ongoing conservation ensures that the wonders of the Piazza dei Miracoli remain for future generations. The Leaning Tower may get the most attention, but the real miracles in Pisa are the works of art that survived fire, war, and time, allowing us to stand in their presence and marvel at their endurance.

Fantastic post! I knew about the bombing but never realized that such extensive restoration was made. Good thing someone painted the gallery in 1858 as a reference . That stratto technique is amazing. I imagine that one would feel quite small speaking from The Great Pulpit. I too love those sketches. But that vision of hell is very frightening…