Empire of books: The role of manuscripts in the Ottonian Renaissance

Below the fold - An Emperor's Library: the books that shaped a civilisation

Books to rebuild a world

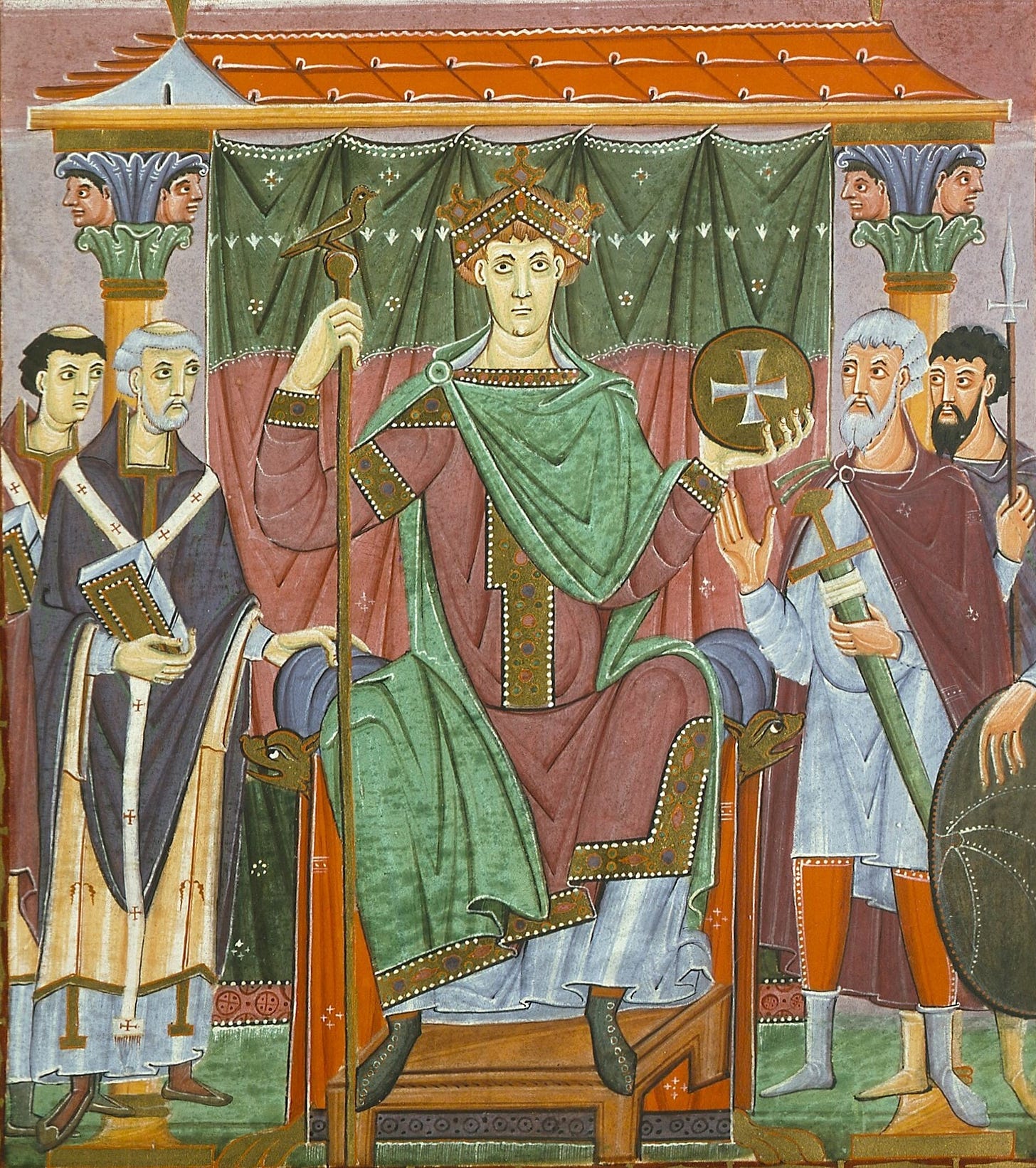

In the 21st century we know about the power of communication and dissemination of ideas that the written word can give. It’s been said many times; internet is the most important development of communication-by-word since the printing press. But in the 10th century, with the printing press still 600 years in the future, rulers understood that power quite well; book production was one of the most important works of the Ottonian emperors, who were consciously seeking to rejuvenate the Imperial idea from Rome and Charlemagne, to create a stable, peaceful and prosperous Christian world.

Making books by hand - it was hard

The achievement of the scribes of this period is all the more extraordinary when you consider what went into making a book. It wasn’t just folding paper and sewing the pages together and writing on them.

First, there was no paper, to speak of. The technique of breaking down cotton or linen fibres in a vat of water with some glue, swishing it about in a frame and letting the water pour out to leave a mat of fibres that dried into paper, wasn’t to come to Europe until the 13th century - another 300 years. For short and temporary written work, like accounting, record-keeping, and correspondence, there were wax tablets, or parchment scraps, but books meant to last had to be made out of parchment.

It’s difficult to calculate, but from the decision to make a book, to the making of the parchment, to making ink and pigments, writing, illustrating and binding, required a host of specialised skills and a colossal investment of time.

Who has this kind of time? Monks.

When we picture medieval monks, we might envision them doing quite a lot of things. But, after praying the Divine Office with the Chant, probably the most popular image of the monastic life of the middle ages involves the copying of manuscripts.

If you’re familiar with the way time seems to flow more slowly in monastic life, it’s not hard to understand how these incredibly time-consuming tasks would have been entrusted to monastics.

In later centuries books were produced by commercial shops peopled with highly trained professional scribes and craftsmen, but in these early times, when monastic life was being reformed and revived, monks were the ideal candidates for large scale book production.

How much time?

Creating a single medieval manuscript was an incredibly labour-intensive process that required thousands of man-hours, especially during the Ottonian period when high-quality, lavishly illuminated books were produced - often on royal commission.

Parchment: ~3,000 – 5,000 hours for parchment preparation alone.

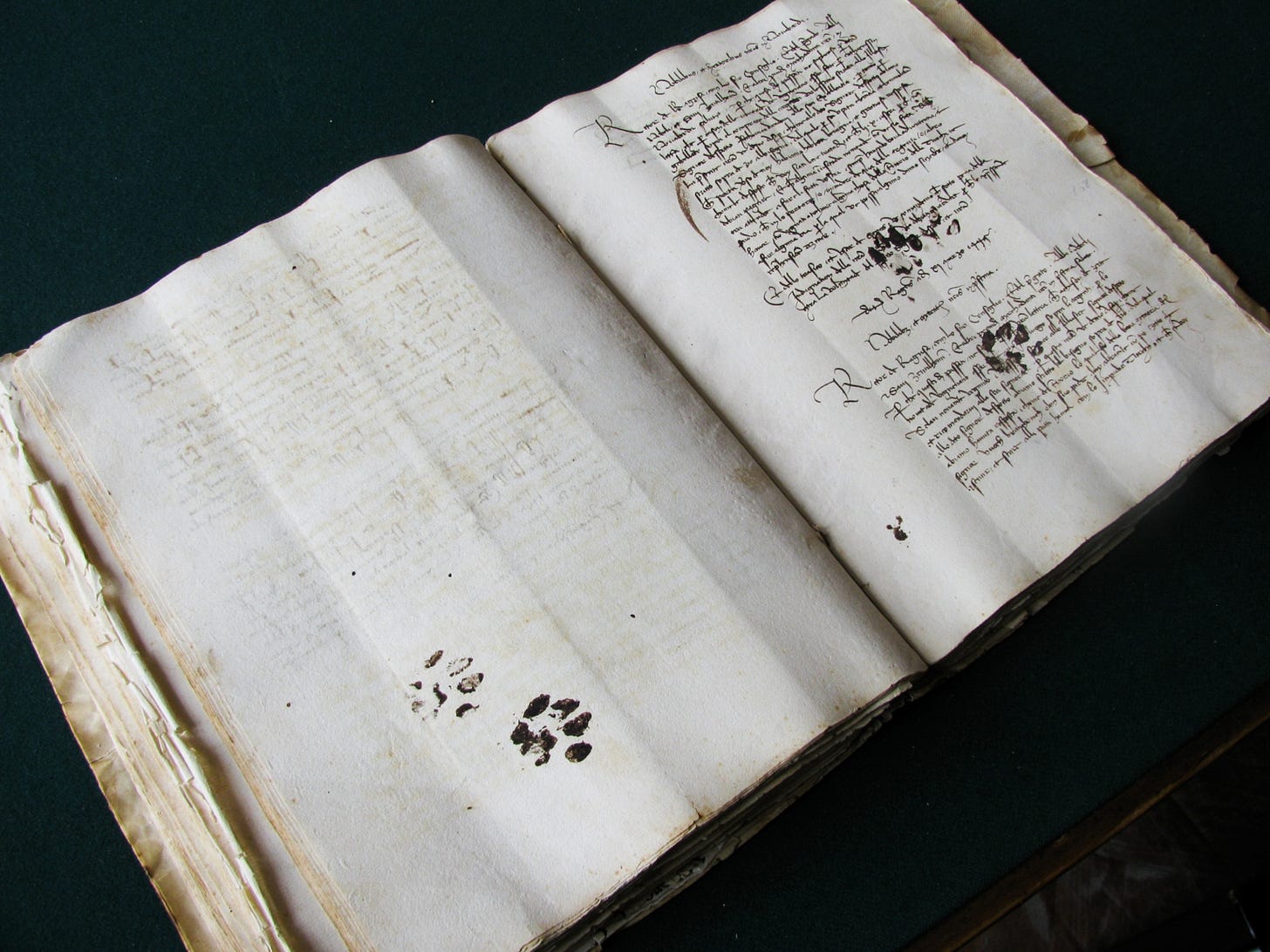

Animal hides (usually from calves, sheep, or goats) were soaked, stretched, scraped, and dried to make parchment. Preparing one hide could take 1–2 weeks. A single manuscript might require 100–300 sheets of parchment with 50–150 hides yielding about 2–3 sheets.

Ink and Pigment Preparation ~100–300 hours for making sufficient ink and pigments for a large illuminated manuscript.

Ink was made from oak galls, lamp soot, iron salts, and other materials, added to a solution of water and gum arabic.

Pigments for illuminations and gold leaf were even more labour-intensive - some extremely toxic - often required early “alchemical” (really just chemical) procedures in a specialist shop to produce.

Writing and Copying ~ 400–800 hours (assuming a scribe worked about 8 hours per day).

Scribes wrote by hand using quills (which of course he had to make himself), often requiring multiple drafts to avoid errors. A skilled scribe could write about 2–4 pages per day.

Total for a book: A medium-sized manuscript, 200 pages, would require 50–100 days of writing for one scribe.

Illumination and Decoration ~1,000–3,000 hours for a lavishly decorated manuscript.

Illuminators added gold leaf, painted miniatures, and decorated initials. This required extraordinary precision and artistry, often taking longer than the writing itself. A fully illuminated manuscript could require 2–4 weeks of work per page, depending on complexity.

Binding ~50–200 hours

The parchment was folded, sewn together, and bound between covers, often made of wood and decorated with leather, metalwork, or jewels.

Estimated total labour: Between 5,000 and 10,000 hours, depending on the size and complexity of the manuscript - a simply mindboggling amount of time and labour to us moderns, accustomed to the daily deadline and scheduled “work flow”. This means if a team of skilled craftsmen worked full-time (8 hours/day), it could take 2–4 years to complete a single high-quality illuminated manuscript.

Painstaking work

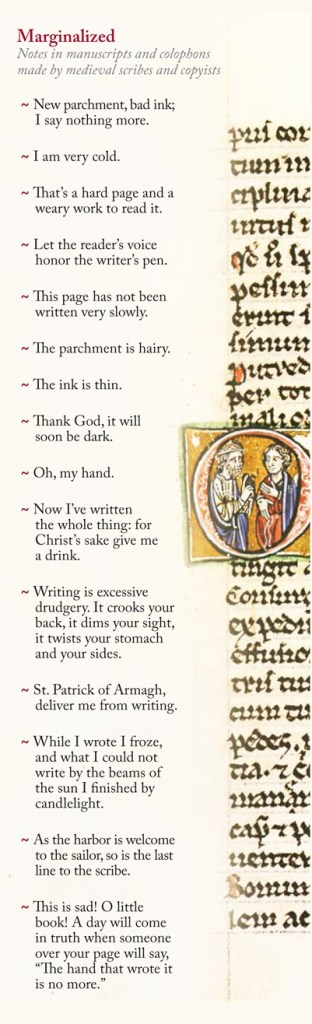

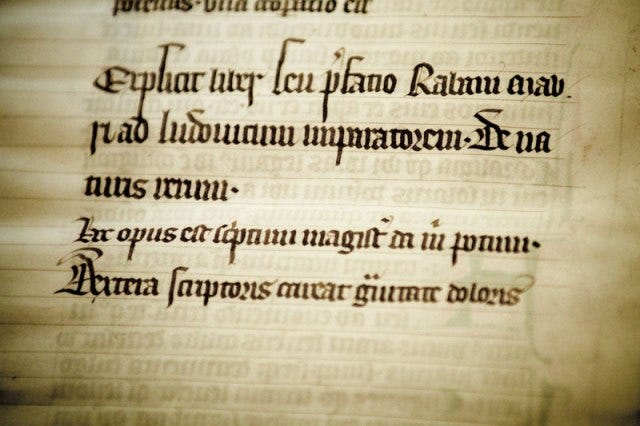

A scribal “colophon” was a short note often added by the writer at the completion of the manuscript, often just to note when the book was completed and by whom.

But occasionally a colophon included complaints about the difficulty of the scribe’s labour.

This one is from the late fourteenth century:

"Pena me fecit, tinta me vicit, plica me trivit, manus me scidit."

("The pen made me, the ink defeated me, the fold wore me out, the hand tore me.")

"Tres digiti scribunt, totum corpus laborat."

("Three fingers write, but the whole body labours.")

“Ardua scriptorum prae cunctis artibus ars est; difficilis labor est, durus quoque flectere colla, et membrana bis ternas sulcare per horas.”

(“The scribe has the toughest job of all; the work is drudgery, and you get a stiff neck from writing six hours day in and day out.”)

It reminds me of the quote from Hemmingway: “Writing is easy. Just sit in front of your typewriter and bleed.”

Without this labour, no civilisation

These books not only enriched the minds and souls of their readers but also played a vital role in reinforcing imperial authority and fostering cultural continuity. Below the fold, we’ll uncover how Otto the Great and his court used these texts to consolidate power and inspire a revival of learning across his empire.

Site update: a franchise reboot for 2025

Following along in our theme of the last few weeks of the year, we’ll be staying in the Ottonian period for both our paid and unpaid sections today, looking at the books that were popular, and how books in general formed the foundation of what we were later to call “medieval” civilisation.

This is the first real content post of our 2025 year, but we’re going to be making some changes starting next Wednesday. We’ll carry on with the same schedule, three posts a week - one in-depth dive into the details, one lighter, more fun and visual post for free subscribers and a double-barrelled post with shorter paid and unpaid sections.

On Monday, we’ll finally get to the “happy ending” I promised way back in the middle of the 9th century, during the “Saeculum obscurum.” Next week, we’ll close out our 2024 work with a post for paid subscribers about the great flowering of monasticism that happened when the Abbey of Cluny was freed from control by secular rulers - and how that allowed the great flowering of medieval sacred art and music that was to culminate in the “12th Century Renaissance”.

After that, on Wednesday, we’re starting a complete “reboot” of the whole site. When we started all this, there were about 1600 subscribers (and zero paid) but now we’re close to 5000, and I feel I kind of owe it to readers to start organising things better. In December 2023, I didn’t have a comprehensive, organised editorial plan.

So far, in approaching “Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of Christian sacred art,” the organising principle was pretty much just, “Oo! Shiny thing!”

So, we’re getting together an editorial plan for the whole year that will present material that a lot of people missed, in a somewhat more orderly way, and help us all get a broader, more comprehensible sweeping view of the whole story. The material will break down roughly chronologically, and topics can be more easily grouped together into ebooks and mini or micro courses, and these can then - finally! - be compiled into proper home school courses.

But at the same time we’re not going to just be strictly chronological (boring!). Of course we’re going to keep looking deeply - especially in the paid member posts - at the overlapping cultural and historical complexities and of course the underlying spiritual meaning of our sacred art patrimony.

So, thanks again to everyone who has been along all this time, and a very warm welcome to everyone who has recently signed up (21 more just yesterday!) Thanks for sticking with me through all my disorganisation and occasional down periods. We’re going to keep going. More on this - and other exciting developments - on Wednesday.

OK, enough backstage stuff. Back to Ottonian books!

At the Sacred Images Project we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. The publication is how I make my living, supported by subscriptions, so apart from plugging my shop, there is no advertising or pop-ups. It’s my full time job, but it’s still not bringing a full time income, so I can’t yet provide all the things I want to and am planning for.

You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week.

For $9/month you also get the second half of the third post, plus a weekly paywalled in-depth article on our great sacred patrimony. There are also occasional extras like downloadable exclusive high resolution printable images, ebooks, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts.

Subscribe to join us below the fold, for more discussion of medieval books, and what they meant to the building of an empire and a civilisation. We’ve got some beautiful high resolution images from some manuscripts of this period.