The complexities of the connections between the Iconoclastic Crisis of the 8th century in the Byzantine Empire, the rise of Islam and the coronation of Charlemagne in Rome - as Emperor of Rome - by Pope Leo III can be intimidating to dive into. So, we’re taking it in stages.

Looking at it closely can show us how medieval western European history developed in its own direction, bringing us to where we are now. As western Christians, 500 years separate us from the enormous change in conceptual framework for sacred art, and 250 years into “Enlightenment” Materialist rationalism. We find it incomprehensible now that Christians in the deep past would be willing to die rather than give up icons in worship. But die, and endure other kinds of persecution, they emphatically did.

Reading about the Iconoclastic crisis, and the courage of the iconophiles was one of the things that made me rethink a lot of the assumptions I hadn’t realised I had about Christian sacred art. It raised questions.

A quick word about sparse posting this week. As I said in the paid member chat this morning, I’ve just had a bit of a turn-down and had to take a couple of days off. I still deal with a pretty severe endocrine imbalance left over from chemo/surgery 12 years ago. I've mostly got it under control with a passel of vitamins and herbal supplements and by being very careful about sleep patterns. But if I let any of that slide, or spend a couple of nights with poor or short sleep or get over-tired, I get a cumulative effect and a crash.

I spent nearly all of Wednesday asleep, and this morning have come blinking owlishly, a bit stunned and slightly wobbly, back into the real world, feeling better. It’s annoying to be such a delicate little snowflake - when I was younger I was a bullet-proof ninja - but I guess it’s better than the alternative, right?

Anyway… I really don’t like breaking my routine and rhythms or messing up my work schedule, but sometimes I can’t work, and I’m grateful for your forbearance.

Today’s post for all subscribers is our third part of the series looking at the impact of Iconoclasm, we’re going to take a broad look at this absolutely crucial moment for western Europe and Christendom. We’ve already taken a brief look at how Charlemagne’s reforms and rebuilding of western European political unity laid the foundation for Medieval Christian Europe. Today we’ll see how this pivotal event was connected to the twin pressures of the terrible Iconoclastic crisis and the growing threat to Christian civilisation of an aggressive new heresy that had taken up the sword: Islam.

The Sacred Images Project is a reader-supported publication where we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. It’s my full time job, but it’s still not bringing a full time income, so I can’t yet provide all the things I want to and am planning for. You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week.

For $9/month you also get the second half of the weekly Friday Goodie Bag post, plus a weekly paywalled in-depth article on this great sacred patrimony, plus our Benedictine Book Club in the Substack Chat. There are also occasional extras like downloadable exclusive high resolution printable images, ebooks, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts.

If you would prefer to set up a recurring donation in an amount of your choice, or make a one-off contribution, you can do that at my studio blog:

Iconoclasm; the ageless pursuit of conquerors and revolutionaries

The urge to destroy visual representations of ideas that have been anathematised goes pretty far back in human cultural history. The pharaoh Akhenaten, who ruled Egypt in the 14th century BC, adopted a form of monotheism centred on the worship of the sun disc Aten. This religious revolution led to destruction of images of Egypt’s old pantheon of gods and the promotion of a new, “Amarna” artistic style. After the pharaoh’s death, his reforms were immediately reversed, and his artistic legacy was systematically erased, his temples, monuments, and artwork destroyed.

And iconoclasm runs as a bit of a theme in the ancient world where conquerors knew a thing or two about subduing a people. The Assyrian kings Sennacherib and Ashurbanipal engaged in iconoclasm as part of their military campaigns, destroying idols and temples of conquered peoples. Darius I of the Achaemenid Persian empire is known to have destroyed the idols of Babylon and other conquered cities.

In the 2nd century BC, Antiochus IV Epiphanes, King of Syria, attempted to impose Greek culture and religion on the Jewish people. This included the desecration of the Second Temple in Jerusalem and the prohibition of Jewish religious practices. The point was to obliterate symbols of cultural identity that is always inextricably connected to religious identity.

In short, the destruction of images and desecration of religious objects was a popular method of cultural genocide throughout the ancient world, and carries on into our own time.

In our immensely visually oriented culture today, no one disputes the importance of man-made images to disseminate cultural, political and religious ideas. And the periodic frenzies of destruction and vandalism of public monuments over the last few years tells us that the iconoclastic impulse has never died out.

People know that images are important as symbols; and that the destruction of those images is itself a symbolic act. These were always calculated, not “senseless,” destructions, in every age.

Byzantine Iconoclasm

Basic terms:

Icons: two-dimensional images of Christ, the Virgin Mary, angels, saints, biblical events, or theological concepts. They are not merely representations but are believed to be an interface between this world and the spiritual realm. Icons are an integral part of the Byzantine liturgy, are venerated as sacred objects and are used in worship, prayer, and meditation.

Iconoclasm: The belief that religious images (icons) should be destroyed because their veneration was considered idolatrous.

Iconophiles/ Iconodules: Supporters of the veneration of icons, arguing they were essential for Christian devotion.

Timeline of Iconoclasm

Islamic conquest of Damascus (634): The city was a major centre in the Byzantine Empire and its capture marked a key victory in the early Muslim campaigns in the Levant, which eventually led to the complete control of the region by Muslim forces and the beginning of the Islamic presence in Syria, which would soon expand further into the Byzantine heartlands, finally leading to its complete overthrow in 1453.

First Iconoclasm (726-787): Initiated by Emperor Leo III, who issued edicts against the veneration of icons, in part due to pressure from Islam, leading to widespread destruction of religious images and persecution of iconodules.

Christmas Day in 800: Pope Leo III crowned Charles, King of the Franks and Lombards, in Rome as Emperor of the Romans, symbolically reviving the Western Roman Empire.

Second Iconoclasm (814-842): After a period of restoration of icons under Empress Irene, Emperor Leo V reinstated iconoclasm.

Second Council of Nicaea (787): The final defeat of Iconoclasm came with its condemnation as a heresy by the Second Council of Nicaea. Since then, this event is celebrated in the Eastern Churches as “The Sunday of the Triumph of Orthodoxy,” on the first Sunday of Great Lent.

Iconoclasm is a Christological heresy

While Iconoclasm manifested with the destruction of images, its true significance lies in its enmity with the Christian doctrine on the fundamental nature of Christ, the Incarnation of the Logos. Iconoclasm is an offshoot and consequence of Christological heresies, the long arguments about the dual nature of Christ as both human and divine. These heresies, when combined with political factors, particularly the Byzantine conflict with Islam, led to the iconoclastic movement.

The defenders of icons believe icons furnish visual reminders of the Incarnation and the life, death, and resurrection of Christ, and all of salvation history. Further, and crucially, they hold that the veneration of icons by the faithful is transferred to the person depicted. As the Second Council of Nicaea defined: “Indeed, the honour paid to an image traverses it, reaching the model, and he who venerates the image, venerates the person represented in that image.”

Iconoclasts argued that the veneration of icons was idolatrous, a violation of the Commandment against the creation of “graven images”. They claimed Christians were worshiping created objects rather than the Creator himself, holding that the Second Commandment, which forbids the worship of idols, applied to any form of religious imagery. Iconoclasts claimed that because of the spiritual nature of God that material representations were inadequate to capture His divine essence.

Christian orthodoxy, however, maintains that iconoclasm is specifically a Christological heresy. It implicitly denies or undermines the full implications of the doctrine of the Incarnation, the teaching that Jesus Christ is both fully divine and fully human. Iconoclasm denies that Christ may be depicted in material form.

By denying the depictability of Christ’s material, human nature, “Iconoclasm implicitly denies the goodness and potential of material things to convey divine grace and participate in the mystery of the Incarnation.”

The Hypostatic Union and the sanctification of matter

In the Incarnation, the Word (Logos) of God became flesh (John 1:14). This means that the second person of the Trinity, while remaining fully divine, also assumed a full and complete human nature, including a physical body that could be seen, touched, and depicted. Iconoclasm, by opposing the veneration or creation of images of Christ, effectively denies that the material world - including Christ's human body - is a legitimate vehicle for representing and expressing the divine.

The doctrine of the hypostatic union affirms that in Christ, the divine and human natures are united in one person without confusion, change, division, or separation. Iconoclasm effectively denies this union by suggesting that Christ’s humanity (which can be depicted) and His divinity (which cannot be depicted) are so distinct that it is inappropriate to use material images to represent Him.

This could lead to a subtle form of Nestorianism, where Christ’s natures are treated as separate to the point where His human nature is almost unrelated to His divine nature, which the Church condemned as heresy.

Orthodox theology, moreover, teaches that through the Incarnation, Christ sanctified material creation. This sanctification includes the use of physical objects (like bread, wine, water, and oil) in the sacraments, and by extension, icons (wood, paint, gold and stone for mosaics) as windows to the divine. By rejecting the veneration of icons, iconoclasm implicitly denies the goodness and potential of material things to convey divine grace and participate in the mystery of the Incarnation.

There is a further implied denial of the sacraments, which always have a material component. If matter cannot convey the divine, this implies doubts about the validity of the sacraments themselves. This can lead to an implied dualism that separates the spiritual and material worlds in a way that is inconsistent with Christ's redemptive work.

Iconoclasm’s rejection of religious images can be seen as a suspicion or devaluation of the material world. By denying that material objects (like icons) can convey or represent the divine, iconoclasm echoes the Manichaean belief in the inherent evil of the material world.

The Second Council of Nicaea, 787

They were those of whom God calls out by prophecy, “Many pastors have destroyed my vine, they have defiled my portion.” For they followed unholy men and trusting to their own frenzies they calumniated the holy church, which Christ our God has espoused to Himself, and they failed to distinguish the holy from the profane, asserting that the icons of our Lord and of his saints were no different from the wooden images of satanic idols.

…We declare that we defend free from any innovations all the written and unwritten ecclesiastical traditions that have been entrusted to us. Council formulates for the first time what the Church has always believed regarding icons. One of these is the production of representational art; this is quite in harmony with the history of the spread of the gospel, as it provides confirmation that the becoming man of the Word of God was real and not just imaginary, and as it brings us a similar benefit. For, things that mutually illustrate one another undoubtedly possess one another’s message.

…we recognize that this tradition comes from the Holy Spirit who dwells in her [the Church] we decree with full precision and care that, like the figure of the honoured and life-giving cross, the revered and holy images… are to be exposed in the holy churches of God, on sacred instruments and vestments, on walls and panels, in houses and by public ways, these are the images of our Lord, God and saviour, Jesus Christ, and of our Lady without blemish, the holy God-bearer, and of the revered angels and of any of the saintly holy men.

…

Certainly this is not the full adoration {latria} in accordance with our faith, which is properly paid only to the divine nature, but it resembles that given to the figure of the honoured and life-giving cross, and also to the holy books of the gospels and to other sacred cult objects. Further, people are drawn to honour these images with the offering of incense and lights, as was piously established by ancient custom. Indeed, the honour paid to an image traverses it, reaching the model, and he who venerates the image, venerates the person represented in that image.

So it is that the teaching of our holy fathers is strengthened, namely, the tradition of the catholic church which has received the gospel from one end of the earth to the other.

Iconoclasm and Empire

Initiated officially in 726 by Emperor Leo III (c. 685 – 18 June 741), iconoclasm led to the destruction of countless religious images and the persecution of iconophiles. The controversy persisted, with intermittent bursts of destruction and restoration of icons - including with an ecumenical council - until Empress Theodora finally definitively restored the veneration of icons in Christian liturgy in 843.

The turmoil weakened the Byzantine Empire, creating internal divisions and reducing its ability to project power both internally and externally. The destruction of icons and other religious artifacts had a significant economic and social impact. The iconoclastic policies had alienated many wealthy and influential individuals, who had previously supported the empire financially and sat in important social and political positions.

An empire is always weakened that suddenly reverses ancient tradition, and begins persecution of those who hold to them, especially with a loss of public trust in elite institutions. This period not only divided the Byzantine Church but weakened the empire’s political unity at a crucial and dangerous time.

The destruction of icons represented a significant cultural loss for the empire. These images were not only religious symbols but also important works of public art that reflected the empire’s rich cultural heritage and connection to its past. Their loss weakened the Byzantine sense of identity and made it more difficult to resist the influence of foreign cultures, an especially pressing concern with the threat of Islam on its doorstep.

Finally, Iconoclasm damaged the Byzantine Empire's relationship with the West. The western half of the Church strongly opposed iconoclasm and eventually the pope excommunicated the Byzantine Emperor Leo III. This schism contributed to the growing divide between eastern and western Christianity, which ultimately culminated in the Great Schism of 1054.

As the Byzantine Empire grappled with this internal strife and its conflicts with the Islamic world, the Western Church, particularly the papacy, took a firm stance against the iconoclast policies. The papacy, seeking to maintain its doctrinal authority and independence, distanced itself from the officially promoted iconoclast position of the Byzantine state, and found a new ally in the Frankish Kingdom, the same increasingly successful political reality whose king was later to be called Charles the Great by history.

Signalling weakness to the empire’s great enemy

Leo had ended a long period of dynastic struggle and political chaos, and established the Isaurian dynasty. He also led successful campaigns against the Umayyad Caliphate, but not without heavy loss of territory, including the fall of such ancient Christian centres as Jerusalem, Antioch, Alexandria and Christian Egypt. His divisive and socially and economically destructive policies on icons weakened his rule at a crucial moment in the history of Christendom’s struggle against Islam.

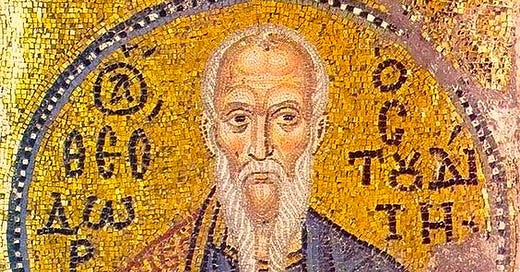

These key losses of Christendom to Islam opened the Christian world to Islamic teaching against images, and plunged Christian thinkers into an ongoing theological debate. St. Theophanes the Confessor - a monk and historian of the Byzantine court who attended the Council in 787 - summarised Leo’s intellectual susceptibility to Islamic criticisms of icons by calling the emperor “the Saracen-minded.”

Leo was accused - mostly posthumously - of being either unduly influenced by Islamic ideas or attempting to appease Islamic rulers by aligning Byzantine religious practices more closely with those of the Muslim world.

Patriarch Nikephoros I of Constantinople (c. 758–828) was a key defender of icons. In his writings, such as the Antirrhetici (Refutations), he argued that the iconoclasts were adopting positions that were more akin to heretical and non-Christian practices.

Much stronger and more direct opposition, during Leo’s lifetime, from Rome was a different matter and reflects the already growing divide between the Byzantine Empire and the western Church.

Pope Gregory II (715–731) was the first Latin Pope to directly oppose Leo’s iconoclastic policies. He wrote letters to the emperor, condemning the actions and defending the traditional use of icons in Christian worship. The pope argued that the veneration of icons was a longstanding practice rooted in the Incarnation of Christ, and he refused to comply with Leo's orders to remove images from churches in the West.

Pope Gregory III (731–741) continued the opposition to iconoclasm. In 731, Gregory III convened a synod in Rome that formally condemned iconoclasm and excommunicated anyone - including by implication, if not by name, a Byzantine emperor - who would destroy or desecrate religious images. This excommunication was directed at the iconoclasts in general, and though it was not a formal excommunication of Emperor Leo III himself, the message was clear.

The mutual opposition to Byzantine policies of the papacy and the Franks helped strengthen the relationship between the Pope and the Frankish rulers, culminating in the coronation of Charlemagne as Emperor by Pope Leo III in 800. This act symbolized a clear and final break from Byzantine influence of the papacy, the Italian peninsula and other western kingdoms, and finally the establishment of a separate western Christian empire.

But the west paid a spiritual price

The political and cultural revival during Charlemagne’s reign, known as the Carolingian Renaissance, contrasted sharply with the internal conflicts of Byzantium, highlighting the diverging paths of Eastern and Western Christendom. The legacy of the iconoclastic controversy extended beyond theological debates, reshaping the political and religious contours of medieval Europe.

The division between east and west went a lot deeper than just politics. Western philosophy and theology, particularly as influenced by St. Augustine, tended to emphasise the physicality of Christ and the importance of the sacraments, and de-emphasise the mystical theology of personal encounter with the divine, which icons facilitated. Even in the early centuries, images didn’t have in the west the transcendent spiritual meaning they did in the east where they were seen as literal manifestations of sacred realities.

Eastern Christian theology tends to emphasize the transcendence of God, His absolute separation from the material world and the pursuit of “theosis” or our transforming union with Him in this life, sanctification. This emphasis on divine transcendence is reflected in the icon’s role as a meeting point between this world and the heavenly realm. This contrasts sharply with the western, Latin Church’s concept of sacred art as a mere representation of a physical, historical reality - events and people in the past with no immediate relationship with the viewer, and decidedly not sacred objects for veneration.

The western Catholic tradition has been heavily influenced by Aristotelian philosophy, which emphasizes the importance of reason and logic in understanding the world, making of Christianity a more cerebral exercise in logic and “development of doctrine,” a trend to which Orthodox Christians still strongly object. This has led to a greater emphasis on rational and systematic theology, which has in turn influenced the later directions of the development of western Christian art.

"An empire is always weakened that suddenly reverses ancient tradition, and begins persecution of those who hold to them, especially with a loss of public trust in elite institutions. This period not only divided the Byzantine Church but weakened the empire’s political unity at a crucial and dangerous time." This is certainly reminiscent of the current situation in Church and State.

BTW An excellent summary. Well done @HILARYWHITE