How do you paint the Invisible God?

It’s Trinity Sunday, and I thought some might enjoy a little rundown that I found in my hand missal of the history of how the Blessed Trinity was depicted in Christian art.

Up to the 12th century God the Father is represented by a hand emerging from the clouds in blessing and often surrounded by a nimbus containing a cross. By this hand is symbolised divine omnipotence. In 13th and 15th century works one sees the face and then figure of the Father. From the 15th Century the Father is represented as an old man in the garb of a pontiff.

Up to the 12th century God the Son was at first represented by a cross, by a lamb or again by a gracious youth, in the same way that Apollo was represented in the pagan world. From the 11th to the 16th century Christ appeared bearded in the prime of life. From the 13th century He is seen carrying the cross and often he is depicted as the lamb.

The Holy Ghost was at first represented under the form of a dove, whose outspread wings often touched the mouths of both Father and Son to show that He proceeds from both. For the same reason from the 11th century He is depicted as a little child and in the 13th century as a youth. In the 15th century He is a man of ripe age, like the Father and the Son but with a dove above His head or in His hand to distinguish Him from the other two persons. Since the 16th century the dove and the fiery tongues are the only two representations of the Holy Ghost. Quite recently it was expressly forbidden to represent Him under a human form.

Since 1628 was also forbidden the monstrous picture of three faces on one body.

Though after the incarnation it became possible to depict God-Made-Man, the problem still remained how to represent the Trinity as a whole. God the Father and God the Holy Ghost are still unseeable with human eyes. So how? This is where things start getting symbolic.

Byzantine or Eastern Christian iconography traditionally never depicted God the Father at all, except as my Missal said, for a symbolic hand, representing divine omnipotence. The hand is the main “interface” we have with the material world, so it is the symbol for the ability to do and create things. The use of the dove to represent the Holy Spirit is even more obviously symbolic. No one thinks the Third Person of the Holy Trinity is really a bird.

The problem with depicting the un-depictable

Most visual representations of the ineffable mystery of the Trinity don’t hit the mark, theologically, and nearly all of them could, if one were trying to be difficult, be accused of some heretical idea. Through the centuries the symbolic Christian art of a given time usually would have been created to respond to and often to correct a popular divergence from the orthodox belief. What was well understood in one time and place will be incomprehensible in another.

As we know, even very precise wording, meticulously argued and refined, can be mis-represented. It’s just a consequence of the Fall. So despite the best efforts of theologically literate artists - or artists commissioned by theologians - misunderstandings are almost impossible to avoid. Looking at the painting above, if one were not very well versed in trinitarian doctrine, could well be a source of confusion, or even scandal for some.

By the 18th century, trifacial or tricephalous Trinity depictions had been around a long time, and at one time did a pretty good job of getting the “three persons in one God” idea across. No one in Perugia attending Mass at St. Agatha’s in the 13th century would have thought that God was literally a man with three heads. And if someone, say a child, did, he would quickly be corrected.

But I’ll admit that for devotional purposes, maybe it was better for these to have died out.

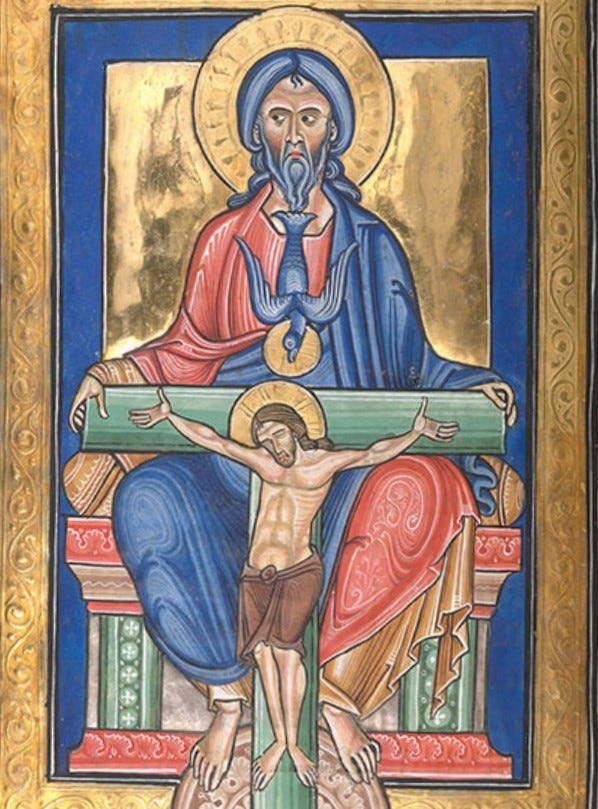

By the period we know as the “Trecento” - the 14th century in Italy, this was the kind of depiction that was the most common in the West, and that we’ve all been used to ever since. It’s called a “Throne of Mercy,” an iconographic type in which the Father presents the Son to the viewer, while a dove representing the Holy Spirit perches atop the crucifix and a symbol of mortal mankind, in this case Adam's skull, sits below.

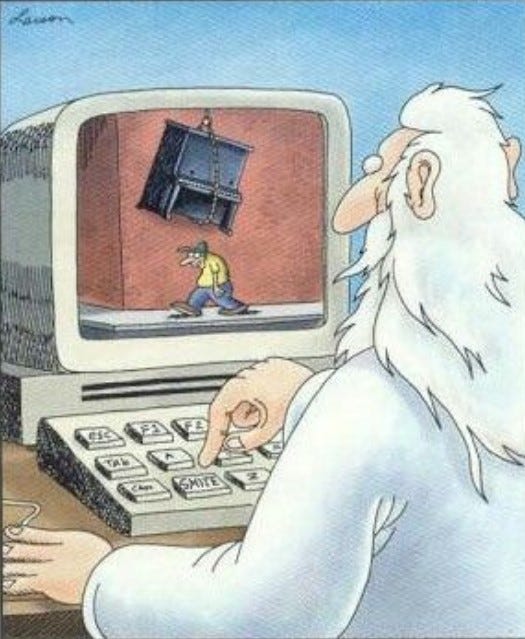

The problem with every one of these is that it can and often does give the wrong impression, particularly in ages like our own when even basic Christian teaching is not commonly known. The great Baroque masterwork by Guido Reni has more or less come to be the standard mental image most of us have of God the Father, and of heaven in general.

We are regularly chastised by good priests for imagining the Father to be an over-dressed old guy with a beard surrounded by flying infants, sitting on a cloud. It’s a cliche. And of course the devout among us consciously reject it, but it’s there and it won’t go away. We have absorbed the visual language that we have seen all our lives.

It’s where this idea comes from:

And indeed, this kind of image has created a culturally ingrained wrong idea about God. It is, in effect, a visual heresy.

Things are very different in the East

All these problems came to the West after the Church was divided irrevocably into Greek/Byzantine East and Latin West. Before that disaster, the visual language of Christian sacred art was understood and agreed upon by all. And as the Western Empire sank slowly into chaos and further division, governed by unlettered barbarians, the East was taken up with the Iconoclastic Crisis, from which - in the end after nearly 200 years of conflict - the language of Christian sacred art was agreed upon.

Iconography is by its nature a deeply incarnational art form. Which means depicting the Holy Trinity is tricky, since sacred iconography has always been extremely careful never to cross the line of idolatry. A fundamental premise of traditional sacred iconography is that the godhead could not be depicted in art, except perhaps in the most abstract symbols, until the Incarnation, until there was a flesh and blood human body to depict.

Given the excruciating difficulty the Christian Church went through in the first four centuries over the definitions of the Persons of the Trinity - even the most minute differences in language sparking violent conflicts - it makes depicting the Trinity a bit of a theological minefield. Do it wrong, and you’re creating a heretical icon. Since the traditional teaching of the Church on icons holds these visual representations as of equal dignity and importance as Scripture itself, that would be a pretty big deal.

The Second Council of Nicea (787) - called to resolve the Iconoclastic Crisis - approved the depiction of the Son of God because "it provides confirmation that the becoming man of the Word of God was real and not just imaginary." But that still leaves us with the difficulty of what to do about the Trinity. Because theology and iconography are not merely closely related but essentially the same thing, the difficulties of explaining the Trinity in words crossed over into difficulties accurately depicting the Trinity in images.

Two sources: Old and New Testaments

In the end the world of canonical iconography decided that the Trinity be divided into two kinds of icons, Old Testament and New Testament, and that these would continue to be very strictly using symbolic, not literal, language.

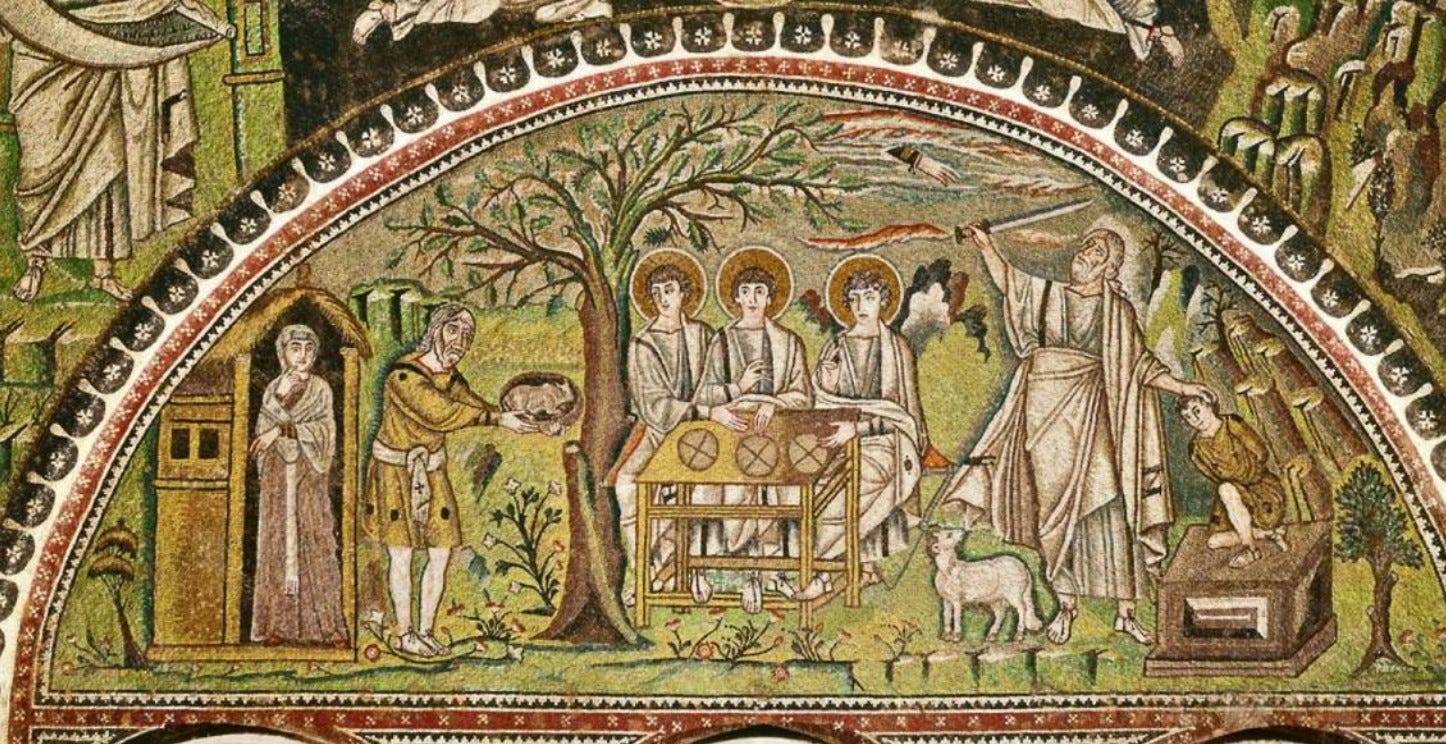

The passage of Genesis in which Abraham is approached at the Oak of Mamre by three mysterious persons has been understood as a description in the earliest part of the Old Testament of an encounter with the Trinity, before the Incarnation of the Logos.

Genesis 18:1–8:

Then the Lord appeared to him by the terebinth trees of Mamre, as he was sitting in the tent door in the heat of the day. So he lifted his eyes and looked, and behold, three men were standing by him; and when he saw them, he ran from the tent door to meet them, and bowed himself to the ground, and said, “My Lord, if I have now found favour in Your sight, do not pass on by Your servant. Please let a little water be brought, and wash your feet, and rest yourselves under the tree. And I will bring a morsel of bread, that you may refresh your hearts. After that you may pass by, inasmuch as you have come to your servant.”

They said, “Do as you have said.”

So Abraham hurried into the tent to Sarah and said, “Quickly, make ready three measures of fine meal; knead it and make cakes.” And Abraham ran to the herd, took a tender and good calf, gave it to a young man, and he hastened to prepare it. So he took butter and milk and the calf which he had prepared, and set it before them; and he stood by them under the tree as they ate.

It’s a very mysterious passage. Note at first how it is clearly “the Lord” that appeared to Abraham. But he looked and “behold, three men were standing by him”. But then when Abraham greets them, he addresses all three in the singular, “My Lord.”

That this has always been understood as the Old Testament acknowledging the Trinity by Christianity can be in no doubt, and part of why we know this, apart from the writings of Church Fathers, is the depictions in images.

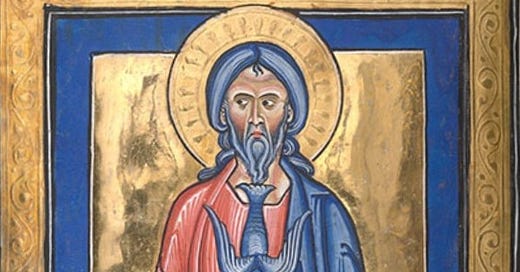

The New Testament manner of depicting the Trinity is more in keeping with what we in the West are used to, with the three Persons depicted separately in symbolic forms, as described above.

This is not a wholly Western Christian custom as we can see from this image from Mount Athos in Greece.

The Holy Ghost is here as a dove that is described in Matthew’s baptism of Christ, which is held as another Scriptural confirmation of the dogma of the Trinity - a “theophany” or manifestation of God: “As soon as Jesus was baptized, he went up out of the water. At that moment heaven was opened, and he saw the Spirit of God descending like a dove and alighting on him. And a voice from heaven said, ‘This is my Son, whom I love; with him I am well pleased.’”

The scriptural reference for this image of God the Father comes from the Book of the Prophet Daniel: “As I looked, thrones were set in place, and the Ancient of Days took his seat. His clothing was as white as snow; the hair of his head was white like wool.”

~

I hope you enjoyed this exploration of traditions in iconography and Christian sacred art of how to depict the Trinity. Please subscribe for more. If you would like to support my work, click on my Ko-fi page, Hilary White; Sacred Art to donate and see my own paintings. Have a blessed and happy Trinity Sunday.

~

Fascinating, thank you!