“What the word communicates through hearing, the painter shows silently.”

St. Basil the Great.

A couple of weeks ago, we started talking about how Italo-Byzantine art came to be, as a mix of Byzantine mysticism, Roman heritage, and emerging Italian styles.

Italo-Byzantine art is what happens when East meets West - when the splendour, mysticism and theological depths of Byzantine icons and mosaics blends with the emerging artistic spirit of Italy. Its roots go back to late antique and early Byzantine artistic traditions as early as the 6th century. It flourished in Italy under Byzantine rule, particularly in Ravenna and Sicily.

It merged with the lingering Roman artistic heritage, particularly in monumental mosaics and church decoration and adopted the Byzantine system of repeatable and recognisable prototypes. At the same time, it interacted with regional Italian styles, which were already developing distinct sculptural and fresco traditions, particularly in the north under the influence of the Germanic “barbarian” tribes. It also coexisted in time with the emerging Romanesque movement.

In today’s post for all subscribers, we can dig a bit deeper into the historical origins and stylistic marks of early Italo-Byzantine art, and see how this artistic blend evolved, setting the stage for what came next.

The other day I published an extra post, asking free subscribers to consider taking out a paid membership if they’d enjoyed the material so far, and asking monthly subscribers to upgrade to annual. And I’m very grateful for the response so far.

The Sacred Images Project has been growing fast, about ten new readers every day which is amazing. But while free subscriptions help the community expand, it’s the paid subscribers who make the deep dives, travel-based research, and exclusive content possible. Over the past month, I’ve published in-depth explorations of San Vitale, Torcello, and the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, plus studies on early Christian art, Italo-Byzantine traditions, and sacred symbolism. And I want to do even more.

I’m working on an end-of-quarter eBook for paid subscribers, packed with summaries, pull-out sections, photos, and maps, ideal for homeschoolers and those looking for a structured deep dive into sacred art. I’m also laying the groundwork for real-world expansion: lectures, seminars, and educational resources beyond just blog posts. But to make that possible, I need more stable support.

If you’ve been enjoying the free posts, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Your support is what allows this work to continue, and to grow into something even bigger.

At the Sacred Images Project we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. The publication is supported by subscriptions, so apart from plugging my shop, there is no advertising or pop-ups. It’s my full time job, but it’s still not bringing a full time income, so I can’t yet provide all the things I want to and am planning for.

You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week.

For $9/month you also get the second half of the third post, plus a weekly paywalled in-depth article on our great sacred patrimony. There are also occasional extras like downloadable exclusive high resolution printable images, ebooks, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts.

I’m happy to offer as a print this little painting I did, in the Byzantine style, for a commission last year; the supplicant figure raising his arms in humble prayer, a visual meditation on the Psalm, Quam dilecta.

It’s in my shop as a wood panel print, but if you prefer we can have it done on different surfaces like museum-quality cotton paper, or canvas.

You can find it in my shop here:

Byzantine tradition to Italian innovation

The Byzantine Backbone

Early Italo-Byzantine art followed the Byzantine tradition of repeatable, sacred prototypes. These icons and mosaics weren’t about personal expression, they were about preserving spiritual truths.

Artists stuck to tried-and-true methods: egg tempera on wooden panels, mosaic, wall frescos, gold backgrounds, and monumental forms in churches.

Early Italo-Byzantine art - we’re talking today about the 6th century to about the turn of the Millennium - wasn’t about individual creativity in the way we think of art today. Instead, it was about continuity, preserving sacred images that had been passed down for centuries. Innovation was simply not valued, and artists were expected to faithfully reproduce holy images using established forms that would be instantly recognised and understood by the faithful. This wasn’t a limitation but a way to ensure that the sacred remained unchanged and recognizable, reinforcing the connection between heaven and earth.

A quick summary of the Byzantine artistic “language”

frontality – figures are depicted facing directly forward, engaging the viewer with a solemn gaze.

hieratic composition – figures are arranged in a way that emphasizes spiritual hierarchy rather than natural movement or perspective.

canonicity – artists followed established iconographic traditions, with fixed poses and compositions that reinforced theological meaning.

lack of naturalism – byzantine art prioritized symbolic representation over realism, avoiding perspective and lifelike proportions.

elongated figures – saints and religious figures appear tall and stylized, emphasizing their otherworldly nature.

gold backgrounds – used in mosaics and panel paintings to symbolize the eternal, heavenly realm.

minimal depth – figures and architectural elements are stacked rather than shown in perspective, keeping the focus on spiritual presence over physical space.

symbolic colour use – colours hold theological meaning; for example, blue for divinity, red for sacrifice, and gold for divine light.

stylized drapery – clothing is depicted with thin, flowing lines rather than realistic folds, enhancing the ethereal quality of figures.

fixed iconographic types – Christ Pantocrator, the Theotokos Hodegetria, and the Deësis composition are repeated with little variation across centuries.

eternal stillness – figures and gestures are restrained, reinforcing the idea of timeless spiritual truth.

large, expressive eyes – eyes are often oversized and almond-shaped, symbolizing wisdom and spiritual vision.

As we’ve discussed many times, Byzantine art, whether in mosaics or painted icons, worked within a strict visual, theological language - they are understood within the eastern tradition as visual theology, in the way that Scripture and doctrine are verbal theology. Certain poses, gestures, and colours had theological meanings. Christ, for example, was often shown as the Pantocrator, with a solemn expression, a blessing hand, and a Gospel book. The Virgin Mary was nearly always depicted as the Theotokos seated on a throne with the Christ Child on her lap, a motif that became the foundation of many Italian Madonna paintings. The reason for this “rigidity” in the visual vocabulary is the same as in a verbal language: so the receiver can understand it.

These images were meant to guide devotion, not just to decorate churches. They were more than images of past events or persons according to the imagination of the painter, but a kind of interface with the divine realm, a place where heaven and earth became one. Gold backgrounds weren’t just an aesthetic choice for example; they were meant to suggest the timeless, heavenly realm, where saints and angels existed beyond the physical world.

Mosaics covered the walls and domes of Byzantine-style churches in Italy, turning entire interiors into shimmering, sacred spaces. The famous mosaics of San Vitale in Ravenna (6th century) are among the best surviving examples, showing Justinian and Theodora, the Byzantine emperor and empress, with an otherworldly stillness that signals their divine authority.

Even though Italy was geographically separate from the Byzantine Empire, the spiritual and artistic connection was undeniable. For centuries, Byzantine art was the “gold standard” of religious imagery in Italy. But things were about to change.

How the Italian touch changed everything

More human figures: Instead of the stiff, distant figures of traditional Byzantine art, Italian artists started making saints and Madonnas look more natural and relatable.

Deeper space and realism: While Byzantine icons were flat and symbolic, Italian painters began experimenting with volume and depth, creating a more three-dimensional feel.

Stories and local flavour: Rather than just repeating the same old sacred images, artists started putting religious figures in recognizable Italian settings, making them feel closer to home.

Even as Byzantine influence remained strong in Italy, small but significant shifts in artistic expression began to take root. Italian artists, while still working within the framework of Byzantine sacred prototypes, gradually introduced subtle variations that reflected their own artistic sensibilities. These changes were not a rejection of Byzantine tradition but rather a natural evolution as Italian artists engaged more deeply with their own cultural and artistic heritage.

Distinctions between Greek Byzantine and Italo-Byzantine art

Regional Influence & Adaptation: began to integrate local Italian influences, particularly in fresco painting and architectural decoration.

Use of Materials & Techniques: while Constantinopolitan Byzantine art emphasized mosaics, icons in egg tempera, and encaustic techniques on wooden panels, Italo-Byzantine art embraced fresco painting alongside these other forms, a distinctly western Roman tradition.

Stylistic Features: Greek Byzantine figures were more rigid, hieratic, and elongated, with minimal expression to emphasize divine transcendence. Italo-Byzantine figures, while still hieratic, often had softer facial features and more expressive gestures, showing a gradual shift toward naturalism.

Spatial Composition & Perspective: Greek Byzantine art maintained flat, two-dimensional spaces, with no emphasis on naturalistic depth or perspective. Italo-Byzantine compositions experimented slightly with volume and spatial depth, particularly in the later stages, foreshadowing early Italian Gothic painting.

Colour & Ornamentation: Constantinopolitan mosaics relied heavily on rich gold backgrounds, deep blues, and reds, creating a sense of celestial grandeur. Italo-Byzantine works often retained gold backgrounds, but began incorporating more regional Italian colour palettes and shading techniques.

Narrative & Iconography: Greek Byzantine art followed strict iconographic conventions, focusing on static, sacred prototypes that were repeated with little deviation. Italo-Byzantine art introduced more narrative elements, especially in later works, leading to an increased emphasis on storytelling through visual sequences.

One of the most noticeable changes was a growing interest in making religious figures appear slightly more natural and humanly expressive. Where Byzantine icons presented saints and the Virgin Mary with a remote, otherworldly detachment, some Italian artists began softening facial features and body language, making figures seem more engaged with their surroundings. The rigid frontality of Byzantine icons remained the norm, but in certain works, there was a hint of movement, a slight turn of the shoulders and head, toward the later 3/4 view, a suggestion of a movement forward toward the viewer and beyond the separate, interior divine space of the icon panel.

At the same time, Italian artists started experimenting with ways to suggest volume and depth, even while still adhering to the Byzantine preference for a flattened, canonical and symbolic space. In mosaics, subtle shading techniques made figures stand out with more three-dimensionality, against their golden backgrounds. While linear perspective as we think of it today - to create the illusion of a space inside the picture frame - would not emerge until much later, there was already a sense that these sacred figures were becoming slightly more physically present, as if they occupied a world just a little closer to the viewer’s own.

The techniques also began to reflect regional preferences and materials regional availability. The Byzantines had perfected the art of mosaic, and their influence ensured that Italy remained one of the great centres of glass and mosaic production. But alongside mosaics, Italian artists were also refining their own fresco traditions, especially in the north, where wall painting had long been a dominant form of artistic expression under the Roman Empire. Sculptural elements in church decoration also bore the marks of local Italian stonework, incorporating details that gave them a distinctly Western feel, even within a Byzantine framework.

These changes were gradual and uneven. In some places, Byzantine influence remained almost untouched, particularly in Venice, which maintained close political and artistic ties to Constantinople. In other regions, however, particularly in Ravenna and Sicily, the interaction between Byzantine and local Italian styles was more dynamic, producing a fusion that, while still recognisably Byzantine, carried the first hints of an emerging Italian artistic identity.

The disaster of the Fourth Crusade (1204) - Venetian Byzantine

The Sack of Constantinople: 1204, a catastrophe for the Byzantine Empire.

Suddenly, Italy was flooded with Byzantine treasures; icons, mosaics, illuminated manuscripts, and sacred relics.

Venice, always a bit of a cultural melting pot, became the epicentre of Italo-Byzantine fusion. Artists there absorbed the Byzantine influence but gave it a distinctly Italian spin.

The Sack of Constantinople in 1204 wasn’t just another episode in the long and turbulent history of medieval warfare, and while it was a political and economic catastrophe for the Byzantine Empire the art looted from the ancient eastern Roman imperial capital constituted an unprecedented artistic windfall for the West, particularly for Venice. You can still go to the treasury of San Marco, and see the incredible objects that were taken.

The Fourth Crusade, originally meant to reclaim the Holy Land, took an unexpected detour when Crusaders, largely financed by the Venetians, ended up attacking and pillaging Constantinople, the heart of Eastern Christianity.

For the first time, the riches of Byzantium flooded into the West in unprecedented quantities. Entire treasures; golden reliquaries, sacred icons, illuminated manuscripts, and the finest mosaics, were seized from churches and palaces and carried off to Venice, France, and beyond. The looting of the imperial capital meant that objects once reserved for Orthodox liturgy and veneration were now placed in Latin churches, where they were often copied and imitated by local artists.

Venice was now overflowing with Byzantine artwork, not just as plunder but as cultural inspiration. Byzantine influence became an even more prominent part of Venetian artistic identity. The mosaics in St. Mark’s Basilica, which had already been decorated in the Byzantine style, were expanded and enriched with direct reference to the plundered masterpieces. Venetian painters, working in panel painting and fresco, continued using Byzantine gold backgrounds, elongated canonical figures, and stylised drapery, but over time, they adapted these elements into something uniquely their own.

This infusion of Byzantine artistic heritage didn’t just affect Venice. Throughout Italy, the sudden influx of icons and manuscripts provided a new model of sacred art, influencing artists in regions like Tuscany and Umbria. While some regions held tightly to traditional Italo-Byzantine forms, others began experimenting, leading to the gradual shift toward a more expressive, naturalistic style that would continue evolving over the next centuries.

The sack of Constantinople in 1204 was both a tragedy and a turning point. It marked the beginning of the decline of Byzantine power but also ensured that Byzantine artistic traditions would be preserved and transformed in Italy, rather than fading away entirely.

Early Byzantine Icons (6th-7th centuries)

Early Byzantine Icons (6th-7th centuries)

Some of the earliest Italo-Byzantine works were encaustic (wax-based) paintings on wood, with solemn, frontal figures meant for deep spiritual contemplation.

These icons, mainly passed down through Byzantine monasteries, set the foundation for later Italian religious painting.

Iconoclasm in the Byzantine Empire meant that the Christian iconographic visual language was preserved in Italy where it came close to being destroyed in the east.

Some of the earliest surviving Byzantine works were encaustic icons, painted using a technique where pigments were mixed with heated beeswax and applied to wooden panels. This method, known for its durability and brilliance of colour, was widely used in the Eastern Roman Empire and carried over into Italy, where it influenced later sacred painting traditions. These icons, created primarily in monastic contexts, were never seen as mere decorative or didactic artworks but as sacred objects - the equivalent of our western holy relics - to convey the prayers and veneration of the faithful to their heavenly prototypes.

These early icons followed the strict theological framework of Byzantine sacred art. Figures were depicted frontally, their large, solemn eyes creating a direct, almost penetrating gaze that reinforced their spiritual presence. The stylised forms, serious and serene expressions and rigid postures weren’t meant to reflect natural movement but rather a timeless, unchanging reality that existed outside of the physical world.

Because icons were such an integral part of Eastern Christian worship, they became a lightning rod for controversy during the period of Byzantine Iconoclasm (8th-9th centuries). The debate over whether sacred images should be venerated or destroyed shook the Eastern Church to its core, leading to the destruction of countless works of religious art in the Byzantine world. However, some of the earliest surviving examples of Byzantine icons remain today precisely because they were kept outside of Byzantium, often in Italy, where they were sheltered from the iconoclastic purges. This ensured that early Byzantine sacred imagery left a lasting imprint on Italian religious art, helping to lay the foundation for Italo-Byzantine painting.

Though we’ll explore Iconoclasm in more depth later, it’s important to note that Italy became an unlikely refuge for these sacred images, preserving traditions that might otherwise have been lost. These early works would go on to shape the development of panel painting in Italy for centuries to come.

Some famous examples:

Mosaic of Christ Pantocrator, Cefalù Cathedral (c. 1130s-1140s)

While slightly outside our time range, this Sicilian mosaic exemplifies the continuity of Byzantine tradition in Italy. The large, imposing figure of Christ Pantocrator, with His solemn expression and golden halo, is a direct inheritance of Byzantine iconography. The careful use of gold backgrounds, elongated proportions, and stylized drapery all reflect the enduring impact of Byzantine models on Italian sacred art.

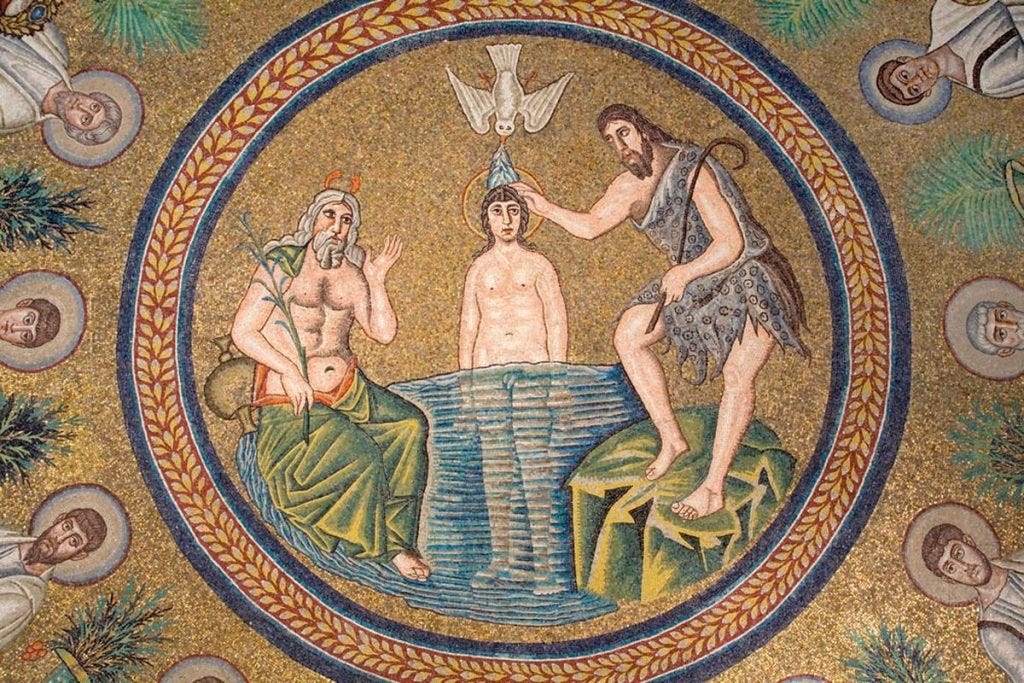

The Arian Baptistery Mosaics, Ravenna (6th century)

Dating back to the reign of Theodoric the Great, these mosaics are an early example of Byzantine influence in Italy. The central dome features a depiction of Christ’s baptism, surrounded by dynamic, stylized figures of the apostles. Unlike later medieval mosaics, these retain a sense of Byzantine symmetry and hierarchy, reinforcing the visual language that would dominate Italian church decoration for centuries. The mosaics of Ravenna in general are marked as very early Italo-Byzantine, not because of any particular naturalism, though that’s present, but because they are so very, very Roman.

The Madonna and Child from Santa Maria in Trastevere, Rome (late 8th-9th century)

This Roman fresco or panel icon, though fragmentary, shows how Byzantine iconographic traditions were maintained in Italy even through the Iconoclast period.

Madonna Advocata (6th century, Rome)

An early version of a type of icon known as the Agiosoritissa or the Maria Advocata, in which Mary is depicted without the Christ Child, with both hands raised in intercessory prayer. One of the few pre-iconoclasm icons that survive that was not held at St. Catherine’s in Sinai. Pious tradition even ascribes the painting to St. Luke the Evangelist, one of several Marian images in Rome that medieval legend attributed to Luke’s hand. According to ancient accounts, the icon was brought to Rome from the East (either Jerusalem or Constantinople) by a pilgrim or refugee before the outbreak of Byzantine iconoclasm in the 8th century.

Christian art is still Byzantine

The Italo-Byzantine tradition was a crucial bridge between Byzantine sacred art and the early Renaissance, but it wasn’t the only piece of the puzzle. Romanesque and Gothic movements extended its lifespan, bringing in new artistic elements that laid the groundwork for the Renaissance boom.

Even as naturalism became the dominant mode of painting, Byzantine-inspired gold backgrounds, structured prototypical compositions, and religious themes endured in Italian religious art for centuries.

Byzantine artistic influence in Italy never fully disappeared. While the naturalistic trends of the Renaissance ultimately overtook the formalist hieratic forms of Italo-Byzantine painting, elements of the Byzantine tradition remained embedded in Italian sacred art for centuries. In Venice, Sicily, and parts of central Italy, gold-ground panel painting, mosaic traditions, and the use of iconic imagery persisted well beyond the medieval period.

Even as Western artists embraced perspective, anatomy, and emotional realism, they continued to reference the structured compositions, stylised drapery, and theological symbolism inherited from Byzantium. Echoes of Italo-Byzantine forms can still be seen in later religious works, demonstrating that this fusion of East and West left an enduring mark on Christian art.

I just want to say that I became a paid subscriber because the history of the church and it’s reflection in art that is portrayed in this Substack is wonderful. I am also using some of the photographs here for meditation during Lent.

Very interesting. Did not know of encaustic iconography or the techniques. The rationale behind iconography was also something I did not know enough about. Really appreciate the work you do.