We’re going to take a very close look at one of the great master works of the 15th century Northern Gothic (or “early Renaissance”), the Portinari Triptych, an altarpiece of the Nativity currently held by the Uffizi Gallery in Florence.

A Philosophical Difference Illustrated: Northern Gothic Naturalism Meets Florentine Renaissance Naturalism

This completely magnificent thing was painted in the city of Bruges, (in modern day Belgium), one of the wealthiest in Europe in the mid 15th century, and the centre of the Northern Gothic and Early Renaissance painting styles - essentially the Florence of the north. It was transported to Florence where it was above the main altar in the Church of Sant'Egidio, a chapel of a hospital, both founded by the Portinari family in the 13th century.

It was commissioned by the Florentine banker Tommaso Portinari who lived 40 years in Bruges. It caused quite the stir in Florence at the time. That city was was already deeply into the Renaissance of Naturalism, that had rejected symbolic, theological interpretations of Biblical scenes in favour of what I call the “time-traveller’s holiday snaps” approach. This is where we are presented with a scene as the painter imagined it might be seen if we were looking through a window into the past - mere naturalism.

To the sophisticated Florentines, this painting would have seemed a reversion to previous styles, but at the same time an almost incredible advancement of technique, with a richness of colour and depth of value (contrasts between dark shadows and highlights) that they would not have seen before. This was made possible by the use of oil instead of egg yolk as a medium for the pigments that substantially changed painting techniques forever.

In the Northern Gothic the theologically-motivated abstractions and symbolism were more successfully blended with stylistic naturalism, using observation of nature and natural perspective, but in service of conveying theological and mystical truths to the viewer.

Florentine Renaissance naturalism, therefore, used sacred subjects to, in effect, subtextually illustrate and promote secular humanist philosophy.

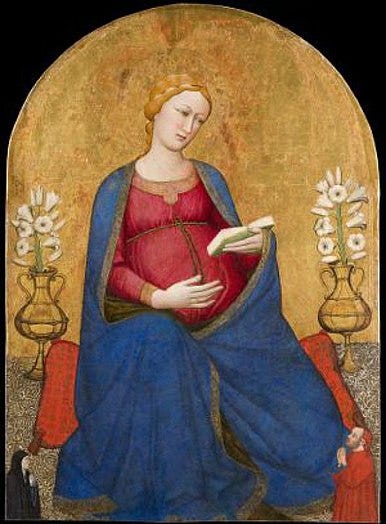

This is also a departure both philosophically and stylistically to previous Italian, more symbolic, paintings like this Trecento Madonna del Parto, by Antonio Veneziano.

Northern Gothic and Northern Renaissance was about something else.

.

A Natural World Minutely Observed

On a small screen the complexity of this image almost drowns itself, so it’s useful to remember that it is a really big painting. The central panel is ten feet wide, so each bit of the fine details would be seen easily if you were in the room with it, either in the church or the gallery. But even at this distance, every child will recognise the scene, because the canons of depicting the Nativity have been faithfully followed. This is the old, traditional concept of Christian sacred art; visual theology rendered symbolically.

The details really are extraordinary when you get a chance to get your nose right up to these paintings - very few of them are roped off, and I actually touched one accidentally once, and set off no alarms. Fortunately these days you can get something of the experience looking very closely at the high resolution digital photographs that many museums are making available.

So we’ll go over it inch by inch.

.

We Know All These People

One of the most striking features of this style of painting are the depths and intensity of its jewel-like colours. This was achieved by the transition from egg tempera to oil paint that was pioneered in the north by Jan Van Eyck. If this were an Italian Trecento painting, the cloth of the angels’ robes would have been done by painting over a ground of gold leaf, and the patterns pulled out by “sgraffito” where the paint is delicately scraped away. In this, the gold is all an illusion.

Though the rendering of the figures is highly naturalistic - exquisitely so - it nevertheless adheres to the ancient “canonical” forms of Christian sacred art - the same that date back all the way to the Christianity of the Roman Empire. We still don’t get the feeling from it that we are looking at a simple depiction of a past event. And we recognise everything in this painting, every person and element that is present here is what we expect to find in every depiction of the Nativity Cycle.

One aspect worth noting is the use of sharp focus in every scene. In later naturalistic works the painter uses the technique of selectively keeping less important elements in soft, fuzzy focus, a subtle way of drawing the attention of the viewer to what he wants you to see. So background landscapes, for instance, would be left out of focus or only implied with indeterminate shapes, rather than rendered in detail.

But in painting of this period, we are drawn further and further in by the sharp, crisp focus in every element, including objects and figures in the distant background. So we can “zoom in” our attention to see the firm reality of everything so meticulously presented.

And there’s no question that we’re supposed to look closely at the background, and recognise there the full story.

Nature As Symbol

To the medieval Christian, the universe, including every animal, bird, fish and blade of grass, was put there for him, by a loving God who wanted us to have life and that more abundantly. To the medieval viewer, everything in his world is a symbol, a sign that pointed to a higher and much more real reality.

Medieval Christians would not have been hampered by 100 years of sentimental secular imagery about Christmas - no cute pictures of snow-covered trees or kittens wearing bows, or coloured glass bobbles. These were spiritually and biblically literate people, and they would have followed the full liturgical drama that firmly connects the joy of the birth of Christ to His coming suffering, death and resurrection. This is why all medieval depictions of the Nativity include subtle, and often unsubtle, references to the Passion.

One of the things that strikes you right away when face to face with these works is the incredible detail, and lifelike accuracy of each part. In every case, the rendering of flowers and other botanical “background” elements is accurate and meticulous enough to clearly identify species of plants and animals. These are obviously not rendered symbolically, but from observation of the real things. And yet, they are not stripped of their symbolic significance; they are not mere background elements in a naturalistic image, as though the painter imagines he is standing observing the scene. Despite the meticulously natural rendering, it’s not being implied that a jar of these particular flowers just happened to have been placed in the stable by the inkeeper’s wife to freshen the place up.

According to Christian artistic symbolic language, each of these meticulously rendered flower species “means” a different thing. The red lilies are for the incarnate humanity of Christ (or the humanity of his mother) and His Passion to come. White iris stands for purity and virginity. The purple iris is for royalty. Columbine, or Aquilegia as they would have been known, is a symbol of the Seven Sorrows of Mary, an immensely popular devotion in Medieval Europe. The name columbine is for “columba,” a dove - the Holy Ghost - that the flower resembles. Violets are for humility and, as the first to appear in the spring, the rebirth of grace at the Nativity. Red carnations are symbols of the Incarnation of the Logos and the Blood of Christ spilled for the redemption of sinners.

The grape decorations on the vase hearken to the wine that is turned into the blood of Christ at Mass. The golden sheaf of ripe wheat (which would not have been found in any stable in December) is an obvious reference to the Eucharist, and this is emphasised from its position mirroring the Christ Child who lies near by.

One aspect is the differences in scale of the figures, showing their relative stature in the cosmic realms of heaven. Again, this is not supposed to be a historical snapshot. The painter doesn’t want us to believe that a lot of very well dressed giants were standing around reading or chatting at the birth of Christ, while hobbit-sized donors knelt and watched. Donors were placed in the scenes to prompt the faithful to pray for their souls, that they could achieve the heights of holiness of the setting. The saints on all sides would have had devotional significance for the church, convent or hospital for which the work was commissioned.

The saints are identifiable by the usual hagiographical symbols. On the left panel behind Signore Portinari and sons are St. Anthony the Abbot with his hermit’s beard, prayer beads and bell, and the Apostle St. Thomas who holds the spear with which he was martyred.

The right hand panel show us St. Mary Magdalen, with her jar of costly perfumed ointment, and St. Margaret of Antioch who is holding a book while standing on a dragon. Margaret was a 3rd century martyr under Diocletian who was cast into prison. She was visited there by the devil who appeared in the form of a dragon and swallowed her.

Margaret the heroic Christian virgin tore her way out of the beast armed only with a cross - a presumably symbolic story representing her triumph over the temptation to apostatise. Magdalen is depicted here, as was customary, dressed to the nines in the most fashionable style for 15th century Flemish noblewomen, with the brocade patterns of the cloth meticulously rendered.

So packed with multiple layers of meaning and significance is every figure, every flower, in this painting it would take many more pages to convey them all. But we can at least see that there is more going on than a mere depiction of a single event in history.

Even when for stylistic or theological reasons some parts remain somewhat abstracted, whether they’re Florentine bankers, saints, angels or the Christ Child Himself, these are all completely believable figures. This was a time before we thought of mystical reality as somehow equivalent to fairy tales or imagination - the realm of heaven was real. In fact the sacred realm was more real to them than the mere material world we inhabit from day to day.

This very great painting uses a stylised, abstracted and idealised naturalism to successfully convey a higher mystical reality. This is naturalism but in service to mystical symbolism. So in the end we have an elevated nature, one drawn up into mystical heights, a natural world “re-enchanted” as we say today, in which every object, every blade of grass, flower and bird is suffused with higher divine meaning.

Beautifully described, thanks Hilary this is a wonderful post. Wishing you a blessed and Holy Christmas. With prayers for you.

I tell my students that they can have this painting to themselves if they visit the Uffizi. It sits opposite Botticelli's Birth of Venus in the gallery. Everyone is huddled around Venus, ignoring a giant masterpiece 30' behind them.