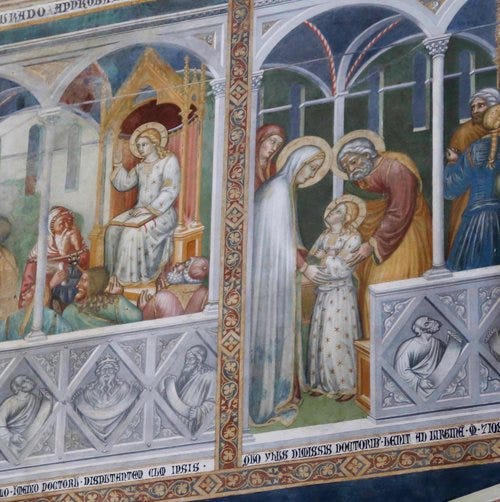

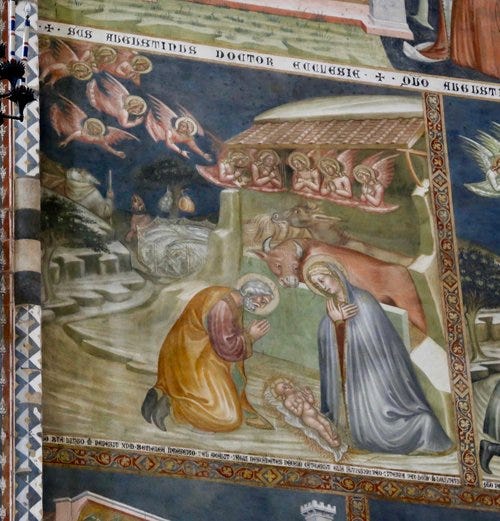

We’ve lost the sense, in the last 500 years or so, that paintings are supposed to mean things. So we look at a medieval or late Gothic painting and usually fail to ask the right kind of questions about it. But for many centuries every single element in a work of sacred art would have a very specific symbolic meaning; a language, that nearly everyone could read.

First, apologies again for my late post. Today is my first day upright and more or less mentally coherent since a bad chest cold descended last week. I’ve been alarming my roommate by coughing like a 90 year-old smoker. But it seems to be letting go today. Back to work.

I’d like especially to welcome the amazing flood of new readers! We still haven’t really stopped growing, and are now a great crowd of 1224 people! And I’d really like to thank those who signed up to become monthly patrons. I look forward to lots of interesting backing-and-forthing in the comments.

I’ve decided to do a big push, planning out what to write about next and stockpiling articles. I’ve found it’s almost impossible to combine writing and painting in the same day, and I often find I can’t finish a whole in-depth piece in a single day on “writing days” and this creates unacceptable gaps in publishing. So my idea is to go hard for a few days and get some posts ready to go, to give myself a good uninterrupted block of concentrated time free for painting. I guess there are some people who could do both, but my brain just doesn’t work that way.

This green button will take you to my studio blog, Hilary White; Sacred Art, where you can see a gallery showing my progress learning how to paint in the traditional Byzantine and Italian Gothic styles. It includes a link to my PayPal where you can make a donation or set up a monthly support to become a patron. Many thanks to those who have already contributed. At the moment, patronages, one-off donations and occasional sales of paintings are my sole source of income.

Upcoming posts on file and in progress will include:

“Canadian mystic: the sacred art of William Kurelek,”

“The Sacred Music of George Harrison,”

“The transgressive arts: what Marko Rupnik’s faux Byzantine mosaics tell us about the modern Church,”

“The Great Western Confidence Trick: how bad philosophy is destroying our civilisation,”

“A post-Soviet contemporary iconography revival: how to get real sacred art,”

“Why Van Eyck, not Leonardo, is the most important name in western sacred art.”

“Techne and Telos: why art means craft, and AI doesn’t scare me.”

“The Virgin of the Dry Tree” - a transitional painting

It very much follows the movement toward naturalism of the late Flemish Gothic, exemplified by the great master Rogier van der Weyden, with softly rounded faces and elaborate drapery folds that imitate life. But at the same time it retains much symbolic language. This is a quintessentially Northern Gothic painting that has left behind the more 2-dimensional, linear and stylised medieval look of its artistic forebears.

We are up north in Flanders now, far from sunny Florence where Fra Angelico is producing the highest order of symbolic, formal, devotional work of his career:

It’s very significant that this little mid-15th century painting is in oils and not egg tempera that had been the standard for centuries, and importantly, remained the standard for Byzantine iconography. Petrus Christus is a follower of the Flemish master Jan van Eyck, the first to start using oil, not egg medium, as the basis of his paintings. This is an important shift; it’s not too far off to call it a revolution. The new medium, in which more opaque and vibrant colours and dramatic values (darks and lights) were possible, allowed a complete change in approach to what sacred art is for and about.

Through the millennia humans have used all sorts of things as media to stick dry pigment particles to a surface, including wax, collagen glue made from boiled animal skins and egg yolk. Paint made from drying oils - those that would dry and harden on contact with oxygen - had been used for decorative work for centuries. But the change in panel painting, particularly for churches, from egg tempera to oils marks the turning point of western art, off in a direction of its own, away from its symbolic Byzantine roots.

The ability of oil paint to give deep, opaque, vibrant colours, without the painstaking layering and translucence of egg tempera, was the basis of the Renaissance’s revolution in rendering “lifelike” illusionistic realism. The goal started to change from creating a mystical meeting place - the church decorated from top to bottom with icons - where the denizens of heaven would come and mingle with worshippers - to making a kind of illusionistic doorway or window into another time and place.

Ultimately illusionistic naturalism of the Renaissance would leave theology behind to focus entirely on the technical aspects of creating the appearance of looking through the picture frame as though through a window, peering at real people in other times and places - the function that photography would later take up. And we have retained this standard of realism for “good art” ever since, until the 20th century backlash against academic painting.

Naturalism and symbolism in harmony - Northern Gothic

Though the typical Byzantine identifiers of the Theotokos and her divine Son - the halos, the stars of royalty on the Virgin’s shoulders and veil, etc.- are almost entirely gone the pair are still recognisable instantly; no one will think this painting depicts just some random woman holding her baby. Importantly, with these delicate gestures and expressions, this is not materialist naturalism but idealised naturalism.

The Virgin of the Dry Tree was obviously a devotional object itself, in the medieval sense of it being used to aid in prayer and contemplation. Its allegorical subject is clearly intended to point to its scriptural and doctrinal sources. Even if they were not improbably standing on a tree, these figures with their symbolic formalism could not be mistaken for ordinary people.

The sumptuous, heavy folds of cloth - in the traditional colours of deep red and blue, depicting the Virgin’s humanity and heavenly royalty - indicate a person of the highest rank, a queen. Her uncovered hair, a major departure from Byzantine canons, indicate that though she is married and a mother, she remains in perpetual virginity. The Child holds a gold orb topped with a cross, the symbol of His kingship over the world.

She stands on a “dry tree” that forms a crown of thorns around her and her Child, an obvious prefigurement of the Passion. The dry tree itself is a reference back to the prophecy in the Book of Ezekiel (17:22-24) where the establishment of the Church is foretold. Mary herself is the “tender” young branch of cedar, cut from the old tree and set high and eminent to take root upon the mountain of Israel, exalted by God from a lowly condition:

“Thus saith the Lord God: I will also take of the highest branch of the high cedar, and will set it; I will crop off from the top of his young twigs a tender one, and will plant it upon a high mountain and eminent.

“In the mountain of the height of Israel will I plant it; and it shall bring forth boughs and bear fruit and be a goodly cedar, and under it shall dwell all fowl of every wing; in the shadow of the branches thereof shall they dwell.

“And all the trees of the field shall know that I, the Lord, have brought down the high tree, have exalted the low tree, have dried up the green tree, and have made the dry tree to flourish. I, the Lord, have spoken and have done it.’”

The thorns of the crown - symbolising the pains caused by human sin - are hung with golden depictions of the letter A, standing for Ave, the first word in Latin of the Hail Mary. This transforms the symbol of suffering to one of intercession - every thorn, that is, every sin, is hung about with Mary's own intercession for mankind who turn to her "sinful and sorrowful". There are 15 of them, representing the Mysteries of the Rosary, often described as Mary's Crown.

The tree in Christian symbolism hearkens to the link between the Fall of Man in the Garden of Eden - the Man and Woman eating of the fruit of the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, breaking the only prohibitive commandment they were given, and causing the fall of all creation. This fall is solved by the "tree" of the Cross, the atoning Passion and Death of God Himself. God has a habit throughout scripture of bringing dead things - in which most people have lost hope - back to life.

Over 20 years ago I found this image of the Virgin of the dry tree and downloaded it. I have always been fasinated by its deep mystical meaning and beauty. Your analysis of it however, has opened fresh depths of meaning for me. Thank you very much for this Hilary . God bless you work.

From the Carmelite Nuns of the Holy Face in Ireland.

Fantastic analysis, will be subscribing! Is there any link to the Theotokos as the burning bush in Exodus? That was my first thought when seeing it. Jonathan Pageau has talked a fair bit about the tradition of it being a thorn-bush, linking to the thorns of Genesis and the crown of thorns in the Gospels. Obviously there are no flames though - although the gold As give it a reflective/illuminated/fiery effect.