When most western Christians think of sacred art, they will usually think of something like this. Leonardo da Vinci’s name enjoys a semi-deified connotation in our minds, associated with the very pinnacle of mastery in the High Renaissance. It almost seems like a blasphemy to us to speak a word of critique, let alone criticism. (So, here goes…)

I’ve been mulling over how to explain to western Christians (“Latins”) what sacred art was before the Renaissance, and why it was a fundamentally different idea from the one we have now. Why “realism” isn’t what they think it is, and that Byzantine icons look like that on purpose and not because they are “primitive” forms. Byzantine painting, with its flat, linear almost cartoon-like symbolic forms and its lack of mathematical “3D” perspective, seems “stiff” and lifeless, remote and unrelatable to us.

But here’s a fun-fact: Eastern Christians don’t think of them that way at all. In the early days of the Byzantine empire, the art was praised for being astonishingly lifelike and lively. This was said especially of the mosaic icons of the great cathedral of Constantinople, Hagia Sophia.

So how did the perspective of our spiritual ancestors change so radically?

At the Sacred Images Project we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. The publication is supported by subscriptions, so apart from plugging my shop, there is no advertising or pop-ups. It’s my full time job, but it’s still not bringing a full time income, so I can’t yet provide all the things I want to and am planning for.

You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week.

For $9/month you also get the second half of the third post, plus a weekly paywalled in-depth article on our great sacred patrimony. There are also occasional extras like downloadable exclusive high resolution printable images, ebooks, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts.

If you would prefer to set up a recurring donation in an amount of your choice, or make a one-off contribution, you can do that at my studio blog.

This helps me a lot because the patronages through the studio blog are not subject to the 10% Substack fee.

I’ve been restocking the online shop with some of the printed items for this year’s Sacred Images Project Christmas market. Like this little Sienese Gothic angel tree ornament:

People tell me all the time - and I’ve found this myself - how difficult it can be to find really nice religious cards and decorations for Christmas. So I’m focusing this year on cards and tree ornaments that will bring some medieval imagery into your holidays.

Enjoy a browse:

Why don’t we like Byzantine icons?

Most western Christians - those from the Latin or Roman branch of Christianity - often say they don’t like or can’t really relate to (what we call for shorthand) Byzantine iconography. I felt much the same when I started my icon painting class three years ago. I only signed up for it because I wanted some formal training in the technique of egg tempera painting - just how to handle the materials. I didn’t care much about Byzantine style sacred art; I felt like it was flat and lifeless and too stylised to really “speak” to me.

But that class started to break down my difficulties, and I have had a full turn-around since then as I learned more and allowed the new (ancient) aesthetic sink into my brain. And I’ve heard other people say the same thing happened to them. What we didn’t understand we couldn’t appreciate.

Renaissance naturalistic humanism deformed our ideas about sacred art

There’s more to this than mere cultural differences in aesthetics between East and West. In a sense with the Renaissance, its “rebirth” of Greek aesthetics and deep dive into naturalism, the relationship between Christianity and art was permanently deformed. And this deformation of the purpose and nature of sacred art ultimately deformed our religious minds as well. We can thank the Renaissance for the abandonment in the West of the canons of traditional sacred art, and the elevation of Naturalism and Humanism above Christian spirituality in art.

Catholics often say that we do not have adequate, canonical iconographic depictions of the Sacred Heart. But there’s a good reason: it’s a devotion that gained currency centuries after the decline of authentic sacred iconography in the West, the take-over of the western Christian mind by naturalism and humanism, almost unnoticed.

So now we only have modern, naturalistic depictions, often heavily sentimentalised.

And this repellent style of art is more or less where we’ve got stuck. Since the division of the Church into two warring camps in the mid-20th century, the “conservatives” have championed this appalling stuff because it represents the “traditional” art of the moment just before the collapse of unity of doctrinal orthodoxy, and the takeover by theological and aesthetic Modernism. But… really? Is this drizzling, effeminate French 19th century sentimentalism - called “Art de Saint-Sulpice” - really what we have to like if we want to be traditional?

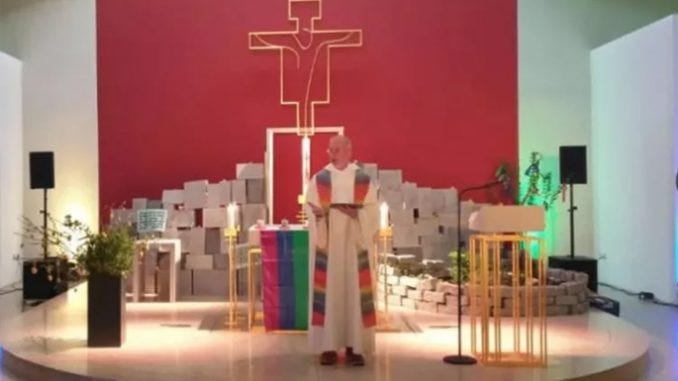

How did we get to the point where our only choices are between late-stage humanistic naturalism and …

… whatever all this is?

Why don't Orthodox Christians like Western sacred art?

One way to learn the reason western Christians don’t like eastern icons, is to learn why eastern Christians don’t like our naturalistic Renaissance-derived art.

Here is a blog post by Stephane Rene, an iconographer who works in the traditional Coptic (Egyptian/Ethiopian) style, who sums it up : "Orthodox iconography vs. Renaissance art." The issue he says, in a nutshell, is naturalism vs. symbolism, a dichotomy that western Christians have all but forgotten exists.

He writes that the Renaissance artists’…

…fascination for realism and the natural world, the introduction of receding perspective in painting engendered a new kind of art, fundamentally different, and at the opposite pole of iconography… [The innovation of linear perspective allowed them to] create an optical illusion of three dimensionality, 3D in modern terms. Hence Renaissance artists became masters at creating optical illusions of the temporal world.

It is noteworthy that many contemporary Byzantine iconographers refer to western naturalism as “illusionism” because the attempt is to create an illusion that the painting is a kind of window showing past events in the world, as photographs do.

Western illusionistic naturalism, they maintain, focuses on the external appearance of earthly, temporal reality, not on supernatural, spiritual reality that can only be rendered visible through symbolic visual language. That symbolic language is what the “canons” of Byzantine art are, and what the west abandoned in the 15th century.

This shift, Rene says, “engendered a new kind of art, fundamentally different, and at the opposite pole of iconography. This radically changed the previously sacred and symbolic character of Western Christian art.”

This is the true enormity of the change from Byzantine and Byzantine-influenced medieval sacred painting to the naturalism and neoclassicism of the Renaissance - not merely a development of painting techniques and styles, but a genuine civilisational shift. And it is why the Byzantine Christian world today continues to reject it for specifically religious, theological reasons.

Rene follows the thought of the Eastern Orthodox world when he says this…

potent mix of perspective and realism with the newly discovered oil medium as a replacement for the traditional egg tempera, accelerated the demise of sacred iconography in the Christian West.

Strong stuff.

One of my cousins is an iconographer. She receives a blessing from her priest and must have all her materials blessed before she even starts making an icon.

Iconography is Scripture and Tradition in color. Every color as well as every symbol has a meaning. That's why there are so many rules governing iconography. It would be like taking the Douay-Rheims Bible and mutilating it into a "teen" bible.

Now how do I get back to "That other time the Church hit rock bottom: the "Saeculum Obscurum""?