I am planning on getting started for-real posting regularly every Wednesday and Saturday, to start with. I realise today is not Wednesday. But I thought I’d add a post - I guess this isn’t an “official” post - explaining a bit more about the project to all the nice people who signed up yesterday. (Creative “momentum” is a concept that writers and painters will recognise; when it comes, get on that train!)

Yesterday’s launch was quite a success, and I’d really like to thank all you who signed up for the emails. I was reading on the Substack “How to” pages that to develop a project like this the first hurdle is the first hundred email sign-ups, after that there seems to be a sort of critical mass that creates momentum. We are a group now of 102, in just under 24 hours.

Technical issues aside, was the encouragement it gave me to hear from you the repeated refrain, “Oh, I’m so glad you’re writing again. We missed you.” After four years (as of two days ago) of social isolation and effective lockdown, I can’t tell you how nice it was to hear. So, I thought I’d add a post welcoming everyone to the little club of World of Hilarity, thanking you all for signing up - it really cheered me up! - and setting down the general gist of the project.

I just updated the “About” page, here, and thought it worth expanding a bit.

[I thought I’d add as a housekeeping note that the reason I’m not set up for paid subscriptions is technical. My bank account is still in Toronto, and my address and phone number are Italian. This is more complexity than the Stripe pay-gateway system is set up to handle. The only way to solve it is for me to actually finally go and set up a new bank account in an Italian bank. If you have ever lived in Italy you will understand the cold clench of dread such a proposal creates in the bottom of your gut. When I came here in 2008 I hadn’t really thought I would stay. Until Brexit I didn’t really have a reason to decide, and before a few months ago it would have been actually impossible. But now I am formally legally resident in Italy - a step toward citizenship - which makes it barely theoretically possible, but that’s all. Handling Italian bureaucracy is a bit of an epic undertaking, not to be approached lightly. Getting an Italian bank account is set in order of difficulty somewhere between Capturing the Cerynaean Hind and Destroying the Stymphalian Birds.

So, until I work up my nerve to start the undoubtedly monstrously stressful process, I can’t use Stripe and therefore can’t set up the paid subscriptions. But if you would like to donate, my Paypal button is here, and I certainly appreciate any help thrown into the tip jar.]

If you think someone else would like these posts, you can send a link:

Choose the world you want, and live in it

When I was a kid growing up in what was then authentically an English colonial town, it was quite normal for families to carry on the old tradition of the “open house”. You’d just let it be known among your general acquaintance that tea would be “put on” for anyone who cared to drop by. There would be biscuits; if you arrived promptly you might get a Bourbon Cream. It was understood that your friends and general acquaintances were welcome to bring along suitable New People who needed introducing to society.

My best friend in elementary school (everyone I grew up around had parents with native English accents) lived in a huge Edwardian manse in Oak Bay, crammed with art and books - writers, artists and assorted oddballs - busy and slightly chaotic, where one could always just stop by for tea at 3 pm and expect a welcome. Very often, if you made a regular habit of it, and were interesting and clubbable enough, the invitation would be extended to lunches and parties. A whole world would open up. (If you were a homeless, parentless but sometimes-useful waif of a teenager, you might even get taken in full time, since there was always a spare back bedroom… But that’s a story for another day.)

I didn’t leave The Island and discover the Big World Outside until I was 19, and I had grown up, despite everything, in a pretty culturally sheltered world. From the time I was old enough to be trusted not to drop the crockery, I had been dressed up in my little frock and pinny and given the task of taking the cake tray around to the ladies at Grandma’s weekly tea parties. It seems like a life out of a fairy tale, looking back on it from the sad perspective of our wrongfully altered contemporary world. But I remember some time in my late 20s and early 30s consciously coming to the decision to go internally back to that world, to embrace the civilised way I was raised and reject the chaotic Modernian existence - the hole - I had fallen into from my teens. I deliberately climbed out, tidied myself up as best I could, and tried to live as best I could as though All That had never happened. It seems as though most of the rest of the world made the other choice.

And I think quite a lot of other people have found themselves looking around and realising they have - some time between about 1998 and 2011 - slipped into the Alice in Wonderland, Spock-with-a-beard Mirrorverse, and are wondering how on earth it came to this. We are stuck now, it seems, in a world in which the old “social contract” of civil society is rapidly disintegrating, replaced with a Hobbesian, Darwinian, Nietzschean dystopic nightmare, where the weak are simply discarded - or worse, are thought to be the lawful prey of the strong. (Hint: we’re all “the weak”.) And we’re wondering how we can fix it.

I’ve been thinking quite a lot about how to fix things, having long ago come to understand that most of civil life is generated from the bottom rungs of the social world, not created by elites and granted like a feudal fief. The larger societal currents are in fact the result of each person individually deciding to live in a particular way, with a particular outlook, particular goals and methods. If I decide to live a chaotic life, untethered to family or community, I make the world more chaotic and less tethered to the concrete realities of family and community. In a rather Petersonian expression; I create a little bit of hell.

This makes me think that it could as easily work the other way. If we decide individually to live in a way that embraces order, family, community, culture, tradition, industry, self-control, self-giving… We make a kind of pocket of heavenly reality come to live on earth. Every one of our decisions creates one or the other, even if we live alone in a farm house in the middle of nowhere in Umbria. If more and more people do that, perhaps the bubbles could expand and maybe join up, and create bigger bubbles. Maybe if enough people do it, these bubbles of recovered civilisation could eventually colonise and crowd out the dystopia.

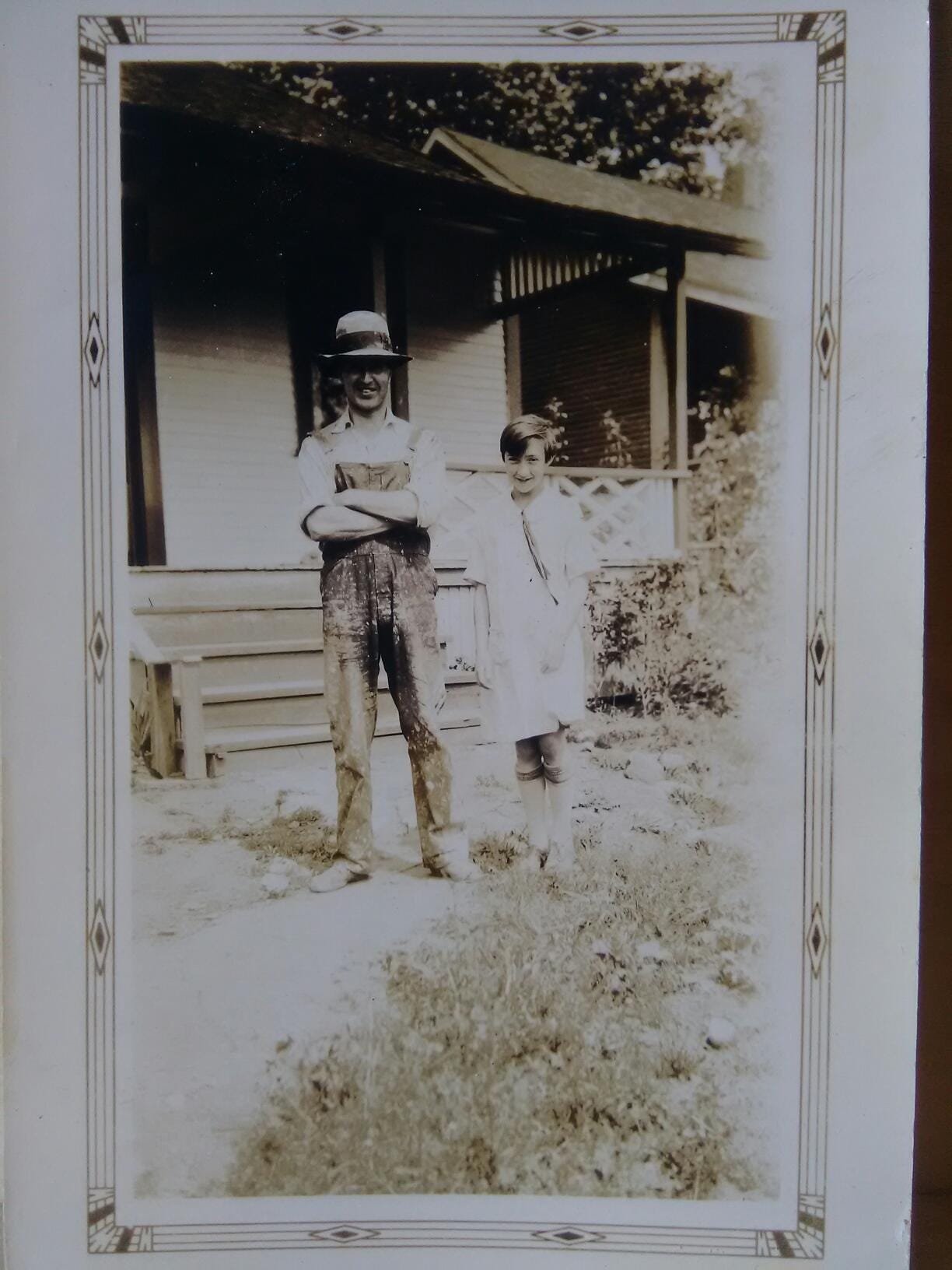

My grandparents (my father’s parents) who were born at the very end of the Victorian era, came to Vancouver Island in the 1920s to be pioneers. It was at that time the very end of the Empire, the absolute fringes. Vancouver Island was barely populated. They came from the centre of the world - Plymouth, Portsmouth and London, leaving behind a Europe that had almost destroyed itself a few years ago, to try to create something civilised, something lasting and good, solid and reliable in a completely new place. In those days you could buy a quarter acre of land - completely raw, barely a road leading to it - for next to nothing (or even actual nothing if you got the government to grant it to you for settling). And then you got to work. In a real sense, they picked up the old civilisation of England, before it went extinct, and transplanted it half a world away.

In the early 1960s, my grandparents built their own retirement house on a little plot of land on the edge of a sea cliff about a 1/2 hour drive into the woods from Parksville, with a group of other English and Scottish pioneers who had come to the edge of the world too. This was after they had helped to build the town, establish arts societies, taught classes, built a high school and a public library, and created a community.

I can find the old neighbourhood now on Google Earth, and what a strange feeling it is! There is our house, still enveloped in the trees; there is the boathouse “Uncle Albert” (my grandparents’ great friend next door) built on the beach; there is Uncle Albert’s big house for his big family; next to that is the twin little houses of Mrs. MacDonald - a teacher from Scotland who came there in the 1930s with her husband Murdough - and Miss Black, Uncle Albert’s spinster sister, also a retired Scottish teacher. Down the road is still Mrs. Toews’ house where I was often brought to play scrabble and take tea with the ladies. Mrs. Toews was a little mad after her husband died, and everyone was careful to help her and make sure she was alright. At The Jib down the road is the big house of Auntie Mickey and Uncle Frank. These properties are now listed as being worth millions, an idea that seems mind-boggling to me now.

The whole place has been built up from the nearly empty woods it was when I was a child and it looks like a suburb. But I remember all these people, their names, their characters, how the ladies used to feed chopped walnuts to the birds on their verandas, how Miss Black collected the porcelain Red Rose Tea figurines and would let me play with them, how Uncle Albert used to take his little boat out fishing in the early mornings in the summer and would often bring us a salmon for dinner, how Uncle Frank had always wanted to be a farmer and grew the most glorious raspberries, and didn’t mind that I would eat more than I put in the bucket.

It was the wilderness, and if you wanted to make a civilisation you had to be pretty tough-minded and determined. You were probably not going to get back to the Old Country more than a few times at most for the rest of your days. So you had to create a world to live in that would benefit you but also create connections, community, just to be able to survive that far away. Parksville was a 2 hour drive Up Island in the 1970s, after they’d built the Island Highway. One didn’t make the trip casually even then. In the ‘20s I can only imagine the level of commitment required to go live there.

The creation of that life required a kind of radical decision for the good; a determination to commit to something that was going to be hard for a long time, but would have echoes down the corridor of time forever. No turning back. No half-hearted measures. (And now that I think about it a bit, creating a little online newsletter for a hundred people seems a bit… Well, one step at a time, I guess.)

But they did, and they built a kind of Anglo paradise, where the best of Edwardian English culture and mindset - the very one now being ridiculed and disdained all over the world - was preserved in a kind of time capsule, well past the time it had died out in the Mother Country. I was raised in the 1960s and ‘70s in an atmosphere in which the Wind in the Willows was a kind of cultural template. People have asked me sometimes why I seem like a person out of time, and the answer is that I saw in my mother - who embraced the chaos of Modernia in the ‘60s and never left it - a stark alternative to the other life, my other upbringing in the world my grandparents had created, and it didn’t require too much thinking to see which one was the better way.

We’re in such a state now that most of the old ways even of thinking about the world seem obsolete. But I think those were good ways, and worth keeping. Worth reviving, and adapting. The Modernia that the world seems to be hurtling toward seems like one I don’t want to live in. But I think too that the idea we must go that way is an illusion. I think it’s been created for us as a kind of assumption; so we won’t try to start imagining other ways and directions.

We are out here on the edge of the old Empire again, it seems, and I think if we want the whole world to be better, the way to do it is not lobbying or activism; I think it’s to create it where we find ourselves right now. And I think we’re obligated to do this by the duty imposed on us by the future. I won’t have children, but I am still part of the human family and have obligations to the future to do whatever I can.

~

For the time being, until I can wade through the Italian banking system, those who want to support me can make a direct PayPal donation here. (If you’re already a subscriber at Hilary White: Sacred Art, deffo consider yourself done. And thanks again.)

"(And now that I think about it a bit, creating a little online newsletter for a hundred people seems a bit… Well, one step at a time, I guess.)." I smiled.

You got it right. Our forebears had something special that we could glimpse for a time. We never could've known, then, how precious it was, it was so ordinary. But to regain it—that little community, that hospitality, that companionship, those open houses (we had those growing up)—especially now that so much of it has practically evaporated, will require all kinds of efforts, not the least of which, this newsletter.

I applaud this effort, and you too, Hilary. And I'm happy to hear I'm one of the first one hundred who do.

What a lovely post. I, for one, completely agree that it's an illusion that we must take the "other road". My family has always lived a bit on the fringes, so I'm no stranger to going about things in completely different ways than most people. It's not always easy, but it can be done, and the result is enormously better. I'm delighted to be one of the first 100 subscribers. I'm very much looking forward to where all this leads.