On Living as a Narnian in Exile

Our desire for goodness, truth, and beauty is not escapism but homesickness.

“One word, Ma’am,” he said, coming back from the fire; limping, because of the pain. “One word. All you’ve been saying is quite right, I shouldn’t wonder. I’m a chap who always liked to know the worst and then put the best face I can on it. So I won’t deny any of what you said. But there’s one more thing to be said, even so. Suppose we have only dreamed, or made up, all those things, trees and grass and sun and moon and stars and Aslan himself. Suppose we have. Then all I can say is that, in that case, the made-up things seem a good deal more important than the real ones.

“Suppose this black pit of a kingdom of yours is the only world. Well, it strikes me as a pretty poor one. And that’s a funny thing, when you come to think of it. We’re just babies making up a game, if you’re right. But four babies playing a game can make a play world which licks your real world hollow. That’s why I’m going to stand by the play world.

“I’m on Aslan’s side even if there isn’t any Aslan to lead it. I’m going to live as like a Narnian as I can even if there isn’t any Narnia.”

In today’s post for all subscribers, we’re going “Off Topic” a bit. I keep seeing people unsure of what to do, caught between awareness of the world’s increasing disorder and the sense that everything happening is far beyond our reach, controlled by forces far above our heads. The weight of it can be paralysing. So, I’d like to suggest something we can do: live in the Real, no matter what spell the world is trying to cast.

I was talking with a friend about that pivotal moment in The Silver Chair. The Green Witch doesn’t simply lie, she does something worse, that lives at the heart of the Modernian proposal: she tries to reshape reality, to lull her victims into accepting a smaller, duller, and false version of the world - but one that seems safe, easy and comforting. She offers them comfort in exchange for surrender.

Puddleglum’s defiance is a heroic refusal to accept the world on false terms, however tempting.

Keeping The Sacred Images Project alive: why your support matters

I just wrapped up the San Vitale post, and my brain’s kind of melting, …

A few weeks ago, I did this plea for free subscribers to consider upgrading to paid. Since then a great many have, and I’m tremendously grateful. This work keeps expanding and none of it would have happened if it hadn’t been for you guys. This isn’t just how I make my living, but I think it can be a path forward for many people who are suffering the uncertainties and strangeness of our time. Thanks for coming along with us.

At the Sacred Images Project we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. The publication is supported by subscriptions, so apart from plugging my shop, there is no advertising or pop-ups. It’s my full time job, and while it’s now providing me with a full time income, we are now looking at growing this into a multi-layered, multi-media project, so I can’t yet provide all the things I want to and am planning for.

You can subscribe for free to get one a week.

For $9/month you also get a second, weekly paywalled in-depth article tracing the history and meaning of our great sacred patrimony. For paid subscribers there are also extra posts with in-person explorations, exclusive photos and videos and materials like downloadable exclusive high resolution printable images. In the works are ebooks, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts.

Greater than which…

Puddleglum’s declaration to the Lady of the Green Kirtle in the climax of The Silver Chair has been called by Lewis scholars one of the most profound statements of faith in all of Narnia; indeed, one of the most memorable in all popular literature. It is not simply an argument against a lie, but an affirmation of truth itself, reality, in the absence of proof. His words articulate the essence of real faith: not mere sentimentality or optimism, but a deliberate act of the will, choosing to live according to what is true, regardless of the world’s denial.

C.S. Lewis wasn’t merely spinning a fairy tale; he was illustrating a reality we all face. The world around us often works in the same way as the Green Witch, not by outright denial, but by making faith, truth, and meaning seem irrelevant, childish, or unnecessary.

Once you start to grow up and out of Narnia, and graduate to Lewis’s essays, mature novels and literary criticism, you start to learn that the insights you gained in childhood from your immersion in Narnia are based on solid philosophical and theological principles.

Lewis was not merely telling stories; he was training imaginations at their most malleable time of life to perceive reality rightly. The convictions that shape Narnia’s world are not mere fantasy but reflect a deeply rooted philosophical reality that stands in opposition to modern scepticism and relativism.

Lewis himself, in an October 1963 letter to Nancy Warner, acknowledged the philosophical weight of this passage. Warner had mentioned that her son had recognised the essence of Anselm’s ontological argument in The Silver Chair.

To which Lewis replied:

I suppose your philosopher son . . . means the chapter in which Puddleglum puts out the fire with his foot. He must thank Anselm and Descartes for it, not me. I have simply put the ‘Ontological Proof’ in a form suitable for children. And even that is not so remarkable a feat as you might think. You can get into children’s heads a good deal which is quite beyond the Bishop of Woolwich.

Anselm’s greatest reality

The Ontological Argument of St. Anselm of Canterbury is a philosophical proof for the existence of God, formulated in the Proslogion (1078).

God, by definition, is the greatest conceivable being, and that a being that exists both in the mind and in reality is greater than one that exists only in the mind. Therefore, if we can conceive of God, He must necessarily exist, because a God who does not exist would not be the greatest conceivable being.

In brief:

God is defined as the greatest being conceivable.

It is greater to exist in reality than merely in the mind.

If God exists only in the mind, then a greater being - one that really exists in objective reality - could be conceived.

This contradicts the definition of God as the greatest conceivable being.

Therefore, God must exist in reality.

This argument has been debated for centuries, with thinkers like Descartes refining it and Kant critiquing it, arguing that existence is not a property that can be attributed to a concept in the way Anselm suggests. Secular philosophers dismiss it out of hand, mostly because most of them don’t believe the existence of God can be proved (or that He exists at all).

Most Catholics - and practically all Thomists - reject it because of the leap from thought to existence. But there have always been supporters in the Church, and it was popular throughout the middle ages. Thomas’ influence meant that it gradually fell out of favour, but it still has its advocates among Catholic thinkers.

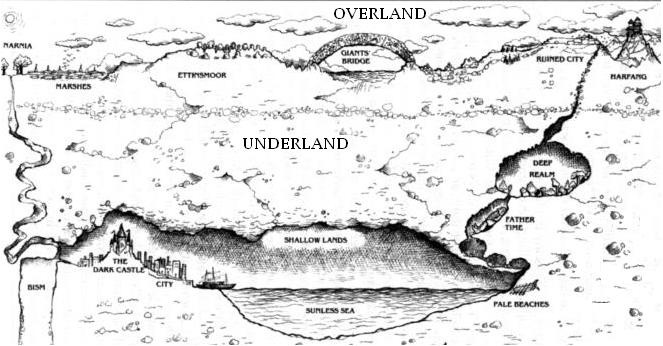

In the context of Puddleglum’s speech, Lewis’s reference to the Ontological Proof suggests that Puddleglum’s defiance is not just an assertion of blind and childish faith but a solid philosophical stance. The reality of Narnia, Aslan, and the Overland is not dependent on whether they can be empirically verified or even “believed” in, but on their necessity within a coherent, meaningful world. It doesn’t matter what we think about them; they exist outside those thoughts and preferences. It’s a very medieval idea that we poor Modernians would dismiss out of hand.

Puddleglum is, in a sense, affirming that if the Witch’s materialist world is all that exists, rocky, dark and empty of meaning, it is an impoverished and false one, because something far greater can be conceived. His speech is not merely an emotional assertion but a distilled version of a long philosophical tradition: the conviction that truth and reality are not contingent upon human perception, but exist independently - a radical idea since the 18th century introduced existential doubt as the guiding principle of modern life.

It is not simply an argument against a lie, but an affirmation of the realness of truth in the absence of mere proof. His words articulate the essence of real faith: not mere sentimentality or optimism, but a deliberate act of the will, choosing to live according to what is true, regardless of the world’s denial.

The Hollow World

It is the moment we find out that the Lady of the Green Kirtle is really one of the “northern witches” of the same sort as Jadis. The Green Witch is a master gaslighter. She does not conquer through open violence but through psychological control. From the beginning, she captured Prince Rilian without force, manipulating him with an enchanted seduction. She appeared to him not as a terrifying enemy, the green serpent, but as a beguiling woman, enchanting him with beauty, charm, and carefully crafted words. She did not force him into submission, she made him want to stay. She became the centre of his world, leading him to forget his past, his duty, and even his father, all while believing he was acting of his own free will. By the time he was bound in the silver chair, he no longer recognised that he was a prisoner at all.

She does what narcissistic gaslighters do: isolates her victims in an environment where she dictates the terms of reality, slowly eroding their confidence in their own perceptions. When confronted with a dis-enchanted Rilian at the end of the book, her strategy is not to physically attack Puddleglum and the children outright, but to convince them that Narnia never existed at all. She does not say, “There is no Aslan,” she says, “You only imagined him, made him something greater than the cat. The cat is real, but Aslan is your wishful thinking,” and “The sun is only a larger lamp.” She recasts truth as fantasy and illusion as reality, making her victims doubt not only what they have seen but the very faculties by which they perceive reality - she makes them doubt themselves to create radical dependence on her and her world.

The Green Witch can be understood in modern philosophical terms as a materialist and reductionist, though her methods are far more insidious than outright denial. She does not argue directly that there is no higher reality, rather, she redefines it, reducing all that is noble, beautiful, and transcendent to something mundane and material. This is the essence of reductionism, the tendency to explain away higher truths by boiling them down to their lowest, simplest components.

She systematically dismantles meaning itself by casting Narnia, Overland, the Sun, and Aslan as mere mental constructs, projections of smaller, material things, just as modern materialists reduce love to chemical reactions, consciousness to neural impulses, and virtue to social conditioning. She does not engage in philosophical debate about reality; she diminishes it. The sun is not an actual sun, she says, merely an exaggerated idea of a lamp. Aslan is not a real lion but a glorified housecat. This is not a rational argument but a psychological assault on perception itself.

But her true power lies not merely in deception, but in offering comfort, making her lie seem preferable. Life in the Real is often difficult, even painful. The children and Puddleglum had suffered greatly to reach the Witch’s kingdom, and more suffering and danger almost certainly lay ahead in the moment of Rilian’s freedom.

When she comes in and discovers the prince free of the chair and his enchantment, she does not rage, she soothes. She offers an alternative to struggle, a world in which there are no dangers to face, no battles to fight, no cause to defend. She lulls them into submission with warmth and quiet, playing on the deepest human temptation: to lay down the burden and accept a world that asks nothing of them. She does not force; she invites.

She makes the real world, the one full of duty, hardship, and sacrifice - but also the only one that contains Aslan - seem distant and unnecessary. She turns courage into foolishness and longing into a child’s dream to be forgotten.

Modernian gaslighting

We live in a time of darkness, deception, confusion and we consequently suffer from a profound distrust in institutions, in authority, in tradition. This scepticism has not arisen without cause; corruption, incompetence, and moral failure have hollowed out once-great pillars of our formerly Christian civilisation. But into this void steps something far more dangerous than broken institutions: a pervasive relativism, a world that does not even acknowledge the existence of truth.

I think the comparison is apt; the Silver Chair always struck me as one of the most difficult and almost bleak of the Narnia series. We feel the children struggle through a harsh and unforgiving landscape, full of unknown dangers; and Aslan himself is absent for nearly the whole book. The Silver Chair mirrors our experience as lovers of Christ lost in this dangerous wilderness. Many of us live isolated except through the connection on the internet; far from the safety and support of the Narnian castle of Cair Paravel. When I was a child, I often wondered why they didn’t simply ask Trumpkin for help; it seemed a hard task.

In our world, Modernia casts very much the same kind of spell the Green Witch does: it doesn’t bother to argue against transcendence, meaning, or moral order, it simply dismisses them as unthinkable, fantasies for children that don’t matter in the hard reality of life.

This is the essence of gaslighting, not merely deception but the manipulation of perception itself. The victim is not just lied to; they are made to question their own capacity to discern truth. The Witch’s enchantment is slow, gentle, even pleasing and entertaining, hypnotic. She does not demand obedience; she makes resistance seem unnecessary. She offers an alternative reality that seems easier, more comfortable, free from struggle. She makes surrender seem rational.

What is the Real?

It was many years after starting to read Lewis as a child that I learned I have a representative philosophical category, even if I will probably never have a political party to call home; I’m an Aristotelian Realist - a very old fashioned thing to be. When I was in my late 20s I was coming back to the practice of the Faith and wanted explanations. I found them in some very old philosophies, that had been out of fashion for centuries.

Aristotelian Realism stands in direct opposition to this form of manipulation. Aristotle held that reality is not something we construct but something that exists independently of us; things have natures that define what they are, regardless of how we feel about them. The Green Witch and the modern world, both deny this and try to sever the link between the mind and reality, making perception itself suspect.

In Aristotelian thought, the sun is real because it exists as a substantial form, not because someone believes in it. Narnia, Aslan, and all that is good and true exist outside the mere perceptions of the characters. Puddleglum’s defiance, then, is Aristotelian in spirit: he chooses to live according to what is, rather than what is convenient or comfortable. He does not create reality; he acknowledges it in humility.

This is why Puddleglum’s response is so crucial to understand for us here in the real world. He does not engage in a battle of logic, nor does he attempt to prove Narnia’s existence on the Witch’s terms. He recognises the deeper game at play: this is not about evidence but about submission. His resistance is an act of defiance - in fact, a violent one, as he stamps out the witch’s fire with his bare foot, extinguishing the sickly sweet spell - against a reality being forcibly imposed upon him.

He refuses to surrender his convictions, even when the world around him conspires to make those convictions seem foolish; he knows who he is and where he is from.

Live in the Real anyway

And that is what it means to live as a Narnian in exile.

We live in an age that erodes faith and virtue by a thousand daily whispers of doubt and distraction. It tells us that truth is relative, beauty subjectively “in the eye of the beholder”, and faith naïve. It pushes us to surrender to a dull, dark, hollowed-out, materialist world where nothing is deeply meaningful and reality only dead matter, where the sacred is ridiculed, and where meaning must be self-constructed from moment to moment rather than revealed. Like the Witch, the world works not by force, but by exhaustion, by making resistance seem futile.

And yet, deep down, we recognise the longing we feel for a world of meaning is not a mirage but a memory, not an illusion but an inheritance. Our desire for goodness, truth, and beauty is not escapism but homesickness. We are not merely people who admire a children’s story about Narnia; we are its citizens, even if we have been displaced.

To be a Narnian in exile is to live in open defiance of the world’s enchantment. It is to refuse to bow to the tyranny of falsehood. It is to hold fast to the truth that there is a real Aslan, a real King and a real Heavenly Kingdom, and a real final victory, no matter how much the world insists otherwise.

This is not a passive stance. It is to reject the seductive ease of cynicism and despair and instead choose fidelity, courage, and hope. Exile is not an excuse for retreat. We are not called to nostalgia, nor to waiting in resignation. We are called to embrace the Real, with all that implies; to suffer courageously, to build, even in exile; to cultivate beauty, to uphold truth, to guard the sacred, to form communities that refuse to fall under the spell. Like the Pevensies in war-torn England, like Jill and Eustace in their grey school days, we are called to prepare. The signs are all around us, and we must keep our eyes open.

One day, the door will open again.

Dear Hilary, this is one of the best things Ive read in a long time. Thanks so much for sharing it on the free side for those of us that can't be a paid subscriber just yet.

Thank you so much for this essay. It is my favorite passage from the Narnia books.