Medieval man focused his hopes in life on the next one. The medieval worldview was saturated with an awareness of mortality and the mysteries of the hereafter. Life’s hardships - from the daily toil, to plagues and famines - imbued people with a keen sense of earthly impermanence. This awareness was not rooted in despair but in the conviction that earthly existence was a mere prelude to the final, eternal state of the soul. This is why medieval artists and theologians alike filled their work with imagery and teachings meant to keep the end of days, as well as individual mortality, in view.

Eschatology became a central theme in sacred art, particularly in the illuminated manuscripts and architectural carvings that depicted apocalyptic scenes. Works like the illuminated Apocalypse manuscripts and frescos vividly expressed this emphasis on the end times, transforming biblical prophecy into visual narratives that captivated medieval viewers. Far from being mere illustrations, these works invited viewers into a contemplative space, where the vision of a world transfigured by judgment and renewal was a constant reminder of imminent divine justice and the possibility of mercy.

In these images, the ultimate mysteries - the nature of salvation, the reality of judgment, and especially the eternal consequences of earthly choices - were presented with an immediacy and frank literalism that we hardly ever hear from the modern Church. Such art served as an ever-present call to be ready, to live morally vigilant lives, guided by the awareness that, at any moment, the apocalyptic scenes depicted could become an immediate personal reality.

In this post for paid subscribers, we’re going to look at some depictions of the Four Last Things. Since it’s the end of October, and our culture still retains a predilection to think about the bigger issues of mortality at this time of year, I thought we could explore the contrast between the medieval and modern worldviews and their impact on both the individual psyche and society as a whole.

The Sacred Images Project is a reader-supported publication where we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. It’s my full time job, but it’s still not bringing a full time income, so I can’t yet provide all the things I want to and am planning for. You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week.

For $9/month you also get the second half of the weekly Goodie Bag post, plus a weekly paywalled in-depth article on this great sacred patrimony, plus our Benedictine Book Club in the Substack Chat. There are also occasional extras like downloadable exclusive high resolution printable images, ebooks, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts.

If you would prefer to set up a recurring donation in an amount of your choice, or make a one-off contribution, you can do that at my studio blog. Of course, anyone setting up a monthly patronage for US $9/month or more will get a complimentary subscription to the paid section here.

This helps me a lot because the patronages through the studio blog are not subject to the 10% Substack fee:

This is the site where I post photos of my own work as it develops. I have a shop there where some of my drawings and paintings are available for sale as prints, as well as some other items.

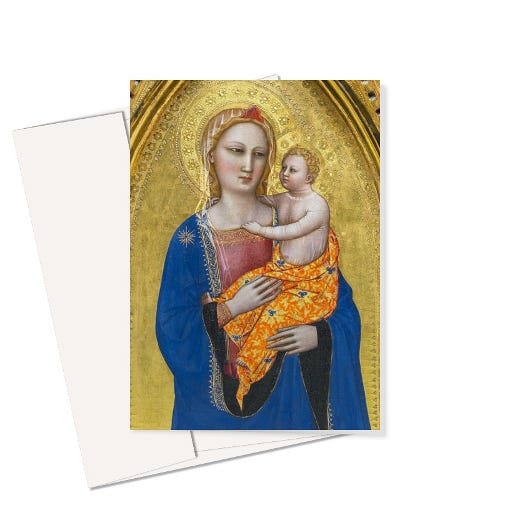

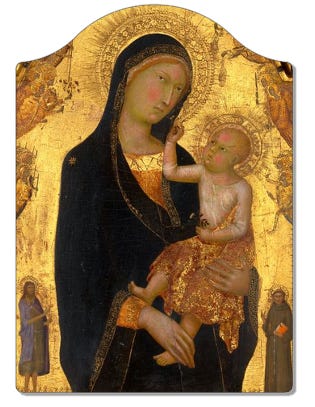

I’ve been doing a lot of shop work recently. This is code for, “Procrastinating on writing by scrolling around the internet looking at the websites of big museums.” It’s a fun internet hobby, but it has also resulted in my finding a bunch of really gorgeous high res images to make available and better known. I’ve turned some of my discoveries into products in the shop that you can have at home.

Explore, browse, daydream, and do a little procrastinating of your own here:

Subscribe to join us below: