The Gothic garden paradise

"A garden enclosed is my sister, my spouse; a garden enclosed, a fountain sealed up."

Despite the multiple woes of Europe between the 14th and mid-15th centuries - including the devastation of the Black Death (~1347-1352) - the period produced some of the most charming and cheerful sacred art of our history.

We all know the symbolic image of a walled garden; it’s a deeply embedded cultural archetype of perfect bliss: an enclosed paradise of flowers, fruit trees, and birds and soft grass, perhaps a tinkling fountain and a few graceful statues. It is populated by delicately beautiful tame birds and beasts - both real and fantastic - and courtly ladies and gentlemen - or angels, as the occasion permits - sitting on soft, herb-fragrant grass, enjoying each other’s gaily dressed company; lutes and harps well represented.

The details are wonderful. As is common in Gothic painting, the plants are carefully and accurately rendered. Violets and wild strawberries imply that it is always both March and May in Heaven. The roses in full bloom tell us that it is also June and July and the golden fruits that it is mellow and fruitful autumn.

This green button will take you to my studio blog, Hilary White; Sacred Art, where you can see a gallery showing my progress learning how to paint in the traditional Byzantine and Italian Gothic styles. It includes a link to my PayPal where you can make a donation or set up a monthly support to become a patron. Many thanks to those who have already contributed. At the moment, patronages, one-off donations and occasional sales of paintings are my sole source of income. If you’ve enjoyed this site, I hope you’ll consider donating so I can keep doing it.

The Hortus Conclusus: a garden enclosed

Some years ago I wrote a piece for 1Peter5 about my gardening efforts, that I undertook as a form of mental therapy after the shock of losing my home in the 2016 Norcia earthquakes. I set about transforming the large garden that came with my tiny rented country flat into a little personal paradise retreat.

Nearly all medieval depictions of the Annunciation – and of Paradise itself – are set in a fragrant and lovely garden of this kind, symbolising the cloistered, contemplative immaculate soul of the Blessed Virgin, miraculously set aside for this one great purpose. This seamless combining of symbolic, mystical and pragmatic elements was something typically medieval, a culture that knew nothing of the harsh compartmentalising that so plagues the thinking of us Moderns. This multilayered concept of the Hortus Conclusus has become a sort of guiding light for me here.

The presence of these walled gardens in much northern medieval Christian art depicting the Virgin and the delights of heaven indicates that it is a central theme of medieval thought. The idea that heaven is like a perfect garden is now deeply embedded in our cultural imagination. The word we use in English, “paradise,” is derived through Latin from the Greek “paradeisos,” meaning an enclosed or walled royal park.

The perfectly beautiful garden where the fruit drops into your hand without work, where everything is living in perfect accord comes of course from Genesis, the paradise from which fallen man was expelled. And the longing for the return to that state of utter peace and accord is deep in every human soul.

Such depictions of the Virgin and Child, and friends, in their lovely medieval gardens show a new idea in Christian art of Europe; the Virgin at home in heaven. This is the Gothic ideal of the home as a place of informality, easy-going intimacy of family life. The exalted company above, famous saints and angels as well as the Child Himself, amuse each other with conversation, music and picking flowers. This is the holy and heavenly population taking their ease.

Gone is the stiff, hieratic, Byzantine formalism of the “court” scenes that are still popular down in Italy, the Virgin and child enthroned, surrounded by a stately, courtly entourage of apostles and saints.

Albertus Magnus of Cologne, philosopher and father of the church wrote about the Hortus Conclusus as, "a representation of the Virgin and Child in a fenced garden, sometimes accompanied by a group of female saints. The garden is a symbolic allusion to a phrase in the Song of Songs (4:12): 'A garden enclosed is my sister, my spouse,'“ the Blessed Virgin herself, whose perpetual virginity is symbolised:

My sister, my spouse, is a garden enclosed, a garden enclosed, a fountain sealed up.

Thy plants are a paradise of pomegranates with the fruits of the orchard. Cypress with spikenard.

Spikenard and saffron, sweet cane and cinnamon, with all the trees of Libanus, myrrh and aloes with all the chief perfumes.

The fountain of gardens: the well of living waters, which run with a strong stream from Libanus.

Arise, O north wind, and come, O south wind, blow through my garden, and let the aromatical spices thereof flow.

But this is not the paradise made by man - utopianism has no place in the divine economy. The scriptures are full of warnings against the folly of human efforts to turn the fallen world, untransformed by God, into an earthly repeat of this perfect bliss. The writer of Ecclesiastes (possibly Solomon himself) decried all such efforts:

I undertook great projects: I built houses for myself and planted vineyards. I made gardens and parks and planted all kinds of fruit trees in them. I made reservoirs to water groves of flourishing trees. I bought male and female slaves and had other slaves who were born in my house. I also owned more herds and flocks than anyone in Jerusalem before me. I amassed silver and gold for myself, and the treasure of kings and provinces. I acquired male and female singers, and a harem as well—the delights of a man’s heart. I became greater by far than anyone in Jerusalem before me. In all this my wisdom stayed with me.

I denied myself nothing my eyes desired;

I refused my heart no pleasure.

My heart took delight in all my labour,

and this was the reward for all my toil.

Yet when I surveyed all that my hands had done

and what I had toiled to achieve,

everything was meaningless, a chasing after the wind;

nothing was gained under the sun.

From Tashbaan to the Hermit of the Southern March

We find this archetype, including the impossibility of creating a genuine paradise on earth, appearing again and again in our literature to this day, right up to the two great Christian fantasy writers of the 20th century. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis both drew from medieval poetry and art, and the Hortus Conclusus appears again and again.

What are the elvish strongholds of Rivendell, the Woodland Realm, and especially Lothlorien, if not examples of the guarded paradise, under constant threat from the evils of the fallen world. Or further back in Middle Earth’s history, the same is found in Gondolin and Doriath, both enclosed elvish paradises, carefully guarded but ultimately lost. And Valinor, the home of the “gods” itself, is a type of the New Jerusalem, the quasi-divine homeland of the earthly but deathless elves, to which they are all in the end drawn by their nature.

.

In Narnia, the true paradise and the false

In Lewis the analogies are more explicitly Christian and drawn from medieval art and poetry. From its first moments, the world of Narnia itself was intended by its creator, Aslan, to be a pristine garden paradise for the sentient “talking animals” and mythical creatures for whom it was made. Later, the boy from our fallen world, who had inadvertently allowed the evil witch-queen Jadis into this immaculate creation, is sent on a salvific quest. Digory must find a mysterious, mystical walled garden on the top of a mountain far to the north, a sacred place, and bring back a silver apple that will be used to protect Narnia for a time from the witch’s designs.

Later we see that Tashbaan, the great pagan city of Calormene, the city of the Tisroc (who certainly won’t live forever), where the demonic Tash is worshipped with human sacrifices, is also a kind of walled garden. But it is reminiscent of the efforts of Solomon above to use raw power and wealth to build an earthly paradise. It fails precisely because it is created by power for only earthly pleasure; its gardens are beautiful but restricted to the use of a proud and corrupt aristocratic and bureaucratic elite.

Tashbaan’s lower classes, who live in squalor, heat and misery, can only catch the occasional breath of a scent of flowers and glimpse of branches wafting over the high walls of their brutal rulers. The visiting Narnian lords, including Queen Susan, quickly realise that even for those privileged to enjoy the material, man-made delights of the city’s gardens and palaces; they can be a fragrant and breezy trap.

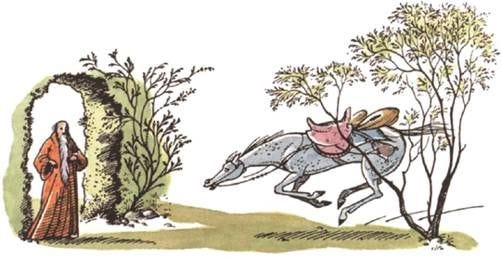

Contrasted with this city of earthly pleasures is the tranquil home of the mysterious Hermit of the Southern March. His little enclosure isn’t a paradise of pleasure, but a refuge of peace and harmony, safety and rest, a hidden place that stands outside the strifes of the world. The Hermit - who is never seen or heard of again in any of the books - lives there within his high green walls in a state of intimate friendship with the Lion Aslan, as well as with his “cousins,” the goats he milks daily. “It was a very peaceful place, lonely and quiet,” and could not be more different from Tashbaan.

It is a remarkable thing that Lewis, the Ulster Protestant and low-church Anglican, would have included a monastic figure like the Hermit in his world. This is a character who lived as one of the ancient saints of the Egyptian and Syrian deserts; pursuing the transforming union with God in solitude and prayer, the divine intimacy sought in the secret enclosed garden of the soul. Maybe the medieval Catholic poetic and artistic mysticism Lewis was drawing from was rubbing off.

The saintly Hermit’s solitude and union with God had granted him the sort of gifts often associated with such figures. He knew all about the greedy Calormene prince Rabadash and his “two hundred horse,” could see them by his “art” of looking into a magical pool crossing the river and invading the northern kingdoms. By this gift he also knew that Shasta must keep running to find the king if the nation would be saved. He is not a sorcerer but an instrument of the divine will, Providence, and shows the signs of it. And he has no greed, even for knowledge. To Aravis he says, “I have now lived a hundred and nine winters in this world and have never yet met any such thing as luck. There is something about all this that I do not understand; but if ever we need to know it, you may be sure we will.”

.

Choose wisely; do the will of God or the will of self.

Later in the series we are also shown the ultimate conclusion of a world governed by power alone for earthly rewards, the fate of Tashbaan if the Tisrocs’ evil designs had been allowed to be fulfilled. We are shown Charn, the great dead ancient city of the sorcerer kings, and given a warning about the final conclusions of that pursuit of power. Lewis, writing the Magician’s Nephew in the mid-1950s, wanted to place before us the potential outcome of using the Deplorable Word in this world.

“The wind that blew in their faces was cold, yet somehow stale. They were looking from a high terrace and there was a great landscape out below them.

“Low down and near the horizon hung a great, red sun, far bigger than our sun…And on the earth, in every direction, as far as the eye could reach, there spread a vast city in which there was no living thing to be seen. And all the temples, towers, palaces, pyramids and bridges cast long, disastrous-looking shadows in the light of that withered sun. Once a great river had flowed through the city, but the water had long since vanished, and it was now only wide ditch of grey dust.”

“‘Look well on that which no eyes will ever see again,” said the Queen. “Such was Charn, that great city, the city of the Kings of Kings, the wonder of the world, perhaps of all worlds.”

The terrible fate of Charn is contrasted with the ending in Aslan’s own country. The stable door has been shut on the dreadful, icy end of the Narnia they knew, but the Friends look around and see something familiar. The blessed realm is remade, but better yet, leads to something greater.

The series ends in a literal paradise; a walled garden enclosing a royal park:

“…They saw a smooth green hill. Its sides were as steep as the sides of a pyramid and round the very top of it ran a green wall: but above the wall rose the branches of trees whose leaves looked like silver and their fruit like gold…Only when they had reached the very top did they slow up; that was because they found themselves facing great golden gates…But while they were standing thus a great horn, wonderfully loud and sweet, blew from somewhere inside that walled garden and the gates swung open…

“So all of them passed in through the golden gates, into the delicious smell that blew towards them out of that garden and into the cool mixture of sunlight and shadow under the trees, walking on springy turf that was all dotted with white flowers. The very first thing that struck everyone was that the place was far larger than it had seemed from the outside…”

Mr. Tumnus the Faun says, “The further up and the further in you go, the bigger everything gets. The inside is larger than the outside.”

This is a very good exploration of an under recognized aspect of Marian art. I have probably read about 100 papers on various paintings of the annunciation in my time studying art, many of which obviously take place in a hortus conclusus, yet it is almost never mentioned, and when it is mentioned it’s as an after thought and not explained.

I think it would be interesting to your readers to comment on the high foreheads of the ladies in

the paintings. Memling's especially, always seem so exaggerated.