The greatest story ever told in pictures; iconographic programmes

Why did churches have a standard ordering of frescos and icons?

The idea of an iconographic programme - a cycle of images telling a sacred story - has a deep history, long predating Christianity. As we saw when we looked at the incredible 40,000 year old paintings of the Chauvet Cavern, human beings have always used ordered visual schemes to express spiritual and cosmological beliefs, hierarchy, power, and transcendence.

The Egyptians filled tombs and temples with scenes structured to guide the soul in the afterlife, recount mythic cycles and reinforce divine order. The Assyrians covered palace walls with narrative reliefs showing the king’s military triumphs, framed by protective spirits and gods, all meticulously arranged to affirm his sacred authority. In the East, Buddhist art developed highly sophisticated iconographic programmes in cave temples and monastic complexes from India to China.

What Christianity did, especially in its formalised Byzantine and monastic forms, was to baptise this ancient instinct, taking that ancient human impulse and reorienting it around Christ, the Incarnation and the sacramental vision of reality. And from that came the rich, layered programmes we see in the apses, domes, and chapels of the Christian world in the west as much as the east.

Well, as Sam said, I’m back.

What a weird couple of months it’s been. Easter came and I was in Santa Marinella having a seaside holiday weekend with friends, helping get ready for the annual Pasquetta party, when the pope died. There was a conclave and the entire Catholic internet went into a kind of frenzy. I found myself dragged into it like it was the accretion disk of a black hole, and ended up mentally exhausted - stretched thin, like butter over too much bread - overstimulated, mentally overwhelmed, over-caffeinated and unable to sleep, think or organise myself. I couldn’t focus long enough to stick to my usual schedule, and I know the programming here got pretty sparse through May.

So, thank you, most sincerely, to readers and friends who checked in, hung out and were patient while things went off course a bit. I needed the time and I’m grateful for the grace to ease back in without pressure. I think the correct ordering of my personal universe has re-asserted itself. So, let’s get back to work.

This week, we’re picking up right where we left off; just starting our dive into Italo-Byzantine art, what it is, how long it lasted, how and why it emerged as a distinctive style from the various crises of the Byzantine empire at the end of the 8th century. And we’ll look ultimately at how it led into the great pantheon of Western Christian artistic styles.

What does it look like? Read more here:

Italo-Byzantine art is what happens when a monastic theology of the image is carried westward by foot and ship and begins to graft itself onto new places and new patrons.

In last week’s paid post, we began to look at what makes Italo-Byzantine art so distinctive, the visual style, mood and the focus on transcendence over realism in the same way as Constantinopolitan work, but adding a distinctive western flavour. We touched on the influence of monasticism, and this week we’ll dig a little deeper into one of the ways theology and sacred purpose shaped it.

In today’s post for all readers, we’ll look at the concept of the iconographic programme; what gets shown, where, and why. This is the deliberate, structured way multiple sacred images are arranged in churches, panels, and fresco cycles to tell a story or send a specific theological message. These weren’t just decorative schemes or storytelling devices. The programmes were carefully composed visual theologies, planned with precision and intended to shape the minds and souls of those who saw them.

At The Sacred Images Project, we explore Christian life, thought, history, and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. This publication is entirely supported by readers — no ads, pop-ups or distractions — just thoughtful work, funded by your subscriptions.

While The Sacred Images Project has grown into my full-time work, we're now building toward an even richer, multi-layered platform, with plans for e-books, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts and more. Your support helps make this expansion possible.

If you’d like to follow along, you can subscribe for free and receive a weekly article exploring the treasures of Christian history, culture, and sacred art..

Paid subscribers ($9/month) receive a second, in-depth article each week, plus additional exclusive posts featuring in-person explorations, high-resolution downloadable images and more.

If you believe in the importance of preserving and deepening our sacred patrimony, I hope you’ll consider becoming a subscriber today.

From the shop: I’m happy to offer this drawing of the Crucified Christ, “Christus Patiens” that I did in the style of the 14th century Umbrian Gothic panel crucifixes. It’s printed on the same museum quality 100% cotton, acid-free paper I drew it on.

You can browse the shop here:

If you’d prefer to set up a monthly contribution in an amount of your choice, you can also do that at the studio blog, or make a one-off donation to help keep this work going. If you subscribe through my personal page, I’ll add you as a complimentary subscriber here. And thank you.

Like a visual parable; a story with a purpose

Far from being our modern simplistic idea of “teaching bible stories” to “illiterate medievals” these churches, painted from top to bottom with whole walls and ceilings of frescos, were intended to pick up and sweep the worshipper into a great cosmic drama.

The closest modern secular analogy to an iconographic programme would probably be the comic book, or comics’ successor, the graphic novel. A well-structured comic doesn’t just string images together; it tells a story through deliberate sequencing, framing and visual emphasis. Every element contributes to the mood and meaning of the story. In a sense, an iconographic programme is like a sacred graphic novel, in which the message isn’t entertainment, but eternal truth.

Of course, the analogy only goes so far. The sacred artist isn’t just telling a story. He’s arranging theological truths in a visual order that reflects the nature of reality as the Church conveys it: ordered, hierarchical, sacramental.

This was especially true in the Byzantine and early medieval world, where sacred art was understood not simply as a devotional aid or visual catechism, but as a kind of theology in image form, shaped by the same principles that governed the liturgy that was understood as an expression of the ordering of the cosmos.

The Sistine Chapel

Probably the most famous iconographic programme in the western world isn’t Byzantine, Romanesque, or Gothic at all, it’s the Sistine Chapel ceiling. A High Renaissance work in style that still draws deeply on the ancient idea that sacred art must be arranged with intention, hierarchy and theological depth.

When you walk into the Sistine Chapel and look up, you are seeing a depiction of a tightly structured cosmos: the Creation, the Fall, the promise of Redemption and the most famous Last Judgment of all. The whole is framed by Old Testament prophets and pagan sibyls, all understood in Christian theology to be leading history, step by step, toward the coming of Christ and the final consummation of the world.

Every element is part of a unified visual and sequential theological programme, designed not just to impress but to call to conversion and make invisible truths visible.

An iconographic programme is a spatial theology, a kind of visual architecture of meaning.

Byzantine programmes - it’s about cosmology

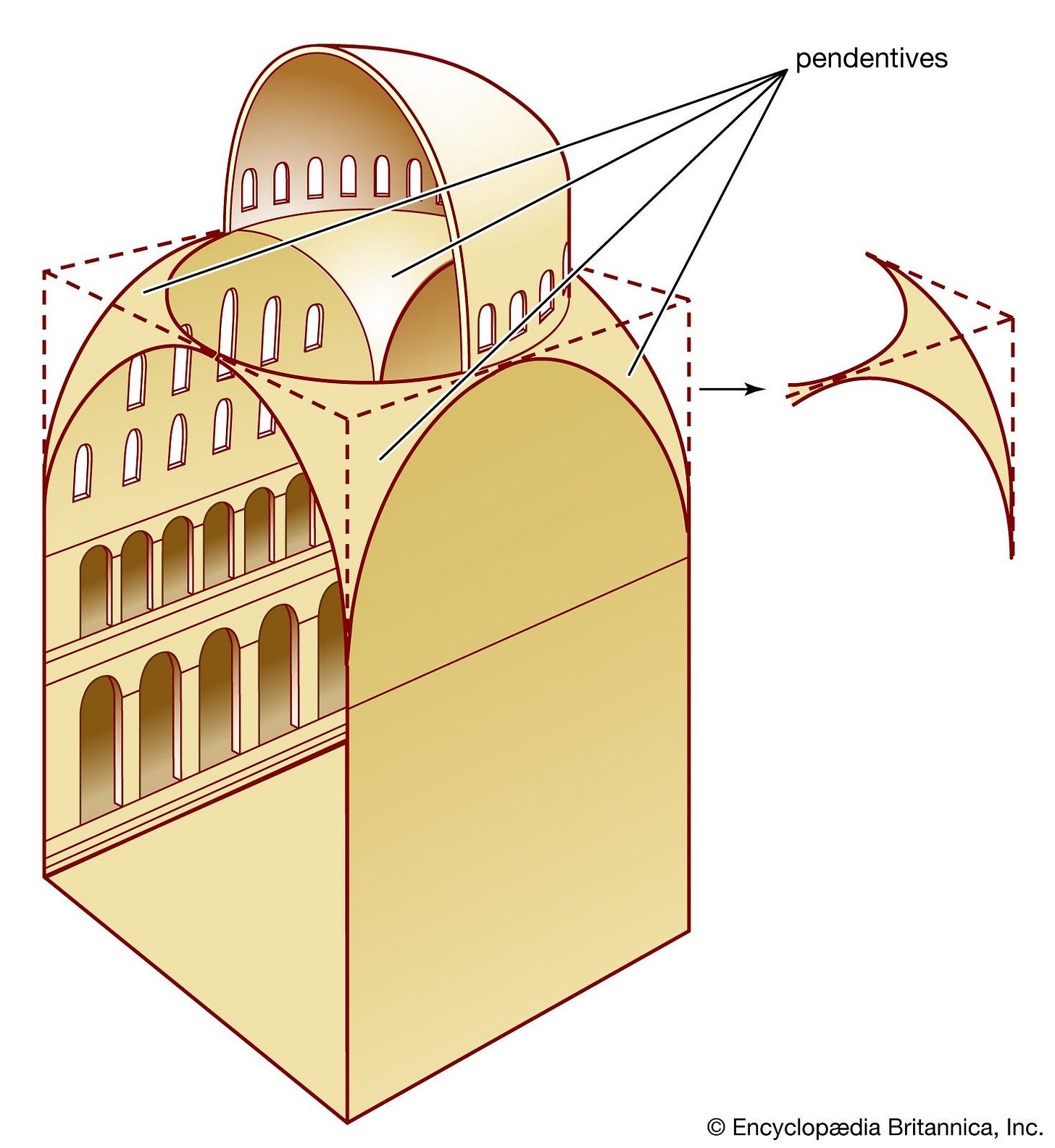

A “standard” Byzantine programme, especially in domed, cross-in-square churches, followed a vertical logic from cosmos to Incarnation, from transcendence to immanence. The whole interior is structured not randomly, but hierarchically, like a liturgical mountain, with Christ at the summit and the faithful below being drawn upward by means of the Church, the saints, and the sacraments.

A Byzantine/Orthodox church is understood as complete when its interior surfaces are properly embellished. Architecture and iconography work together to create a unified entity. The holy images placed in their specified architectural settings create the sacred space for worship and private prayer, a liminal space where the heavenly and the earthly meet.

Bishop Joachim of Amissos, PhD. Director of the Archbishop Iakovos Library at Hellenic College/Holy Cross.

In the Byzantine world, the iconographic programme reached its most systematic and theologically coherent form in churches shaped by monastic influence. These weren’t just pretty interiors, they were whole cosmologies in paint, mosaic and fresco, structured to reflect the spiritual hierarchy of heaven, the liturgical function of the building, and the journey of the soul.

In an article about the decoration of a new church at Saint Gregory of Sinai Monastery, we read: “Before designs for individual wall paintings can be drawn, the overall iconographic plan for the church must be made. A detailed discussion of this plan lies outside the scope of this essay. In very broad outline, however, the plan is developed in 3 cycles”:

(1) the Dogmatic Cycle: a large, central icon of Christ in the dome (if there is one), then a large icon of the Virgin and Child (or Virgin in Prayer) in the apse;

(2) the cycle of the Church Festivals at the top of the walls or on the ceiling; and

(3) the cycle of the Saints at the ground level, surrounding the congregation.

At the highest point, in the central dome, you typically find Christ Pantokrator, the “Ruler of All”, gazing down and blessing from the heavenly realm. This isn’t Christ embedded in any narrative; this is Christ enthroned in eternity, holding the cosmos together with His will.

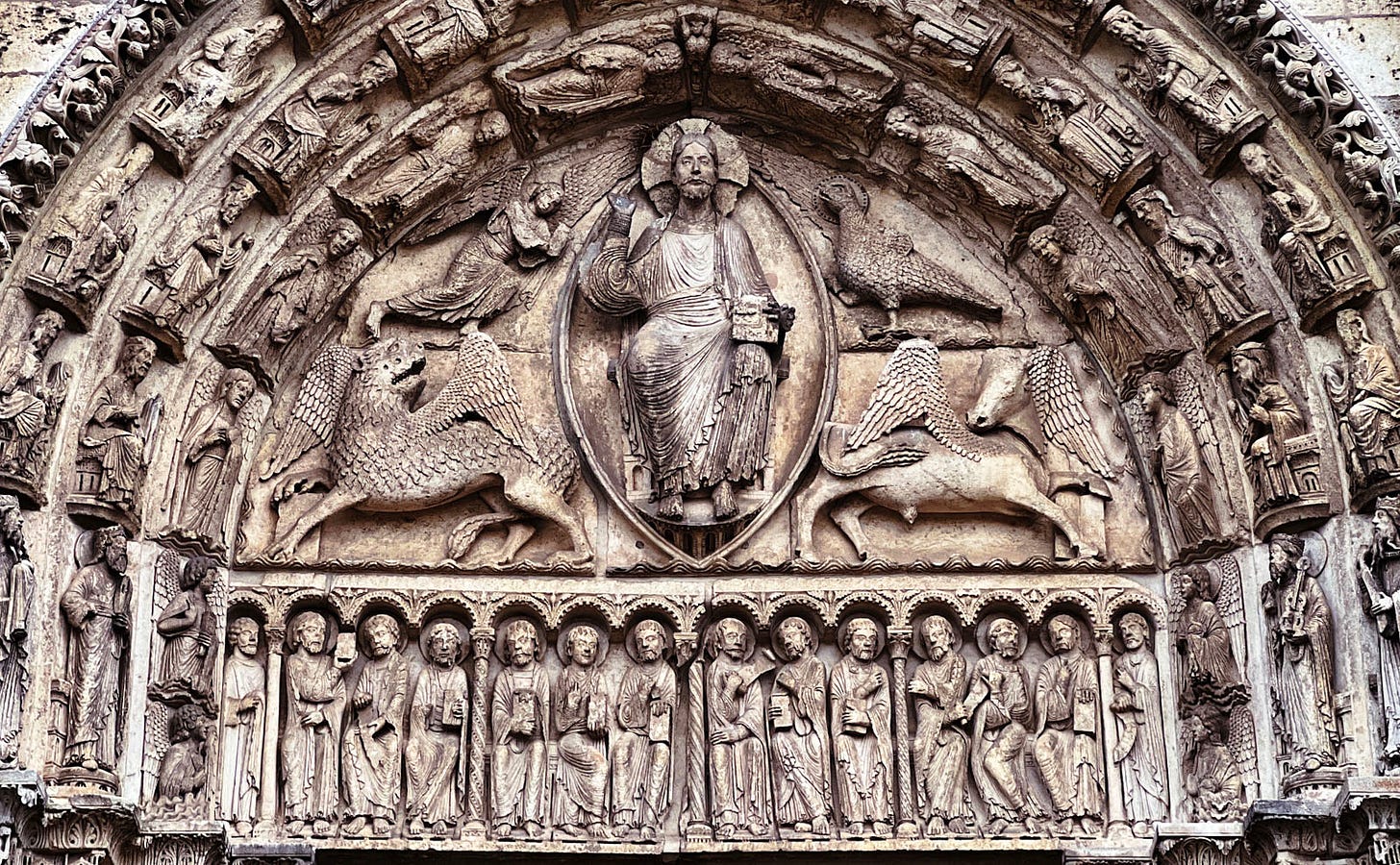

Below Him, in the pendentives or drum of the dome, are often the Four Evangelists, supporting the proclamation of the Word. They are often depicted as their symbols of the winged bull, lion and man and the eagle.

In the apse, above the altar, is usually the Theotokos, the Mother of God, often shown in the Orans posture, supplicating on our behalf, or with Christ Child, emphasizing the Incarnation and her role as intercessor.

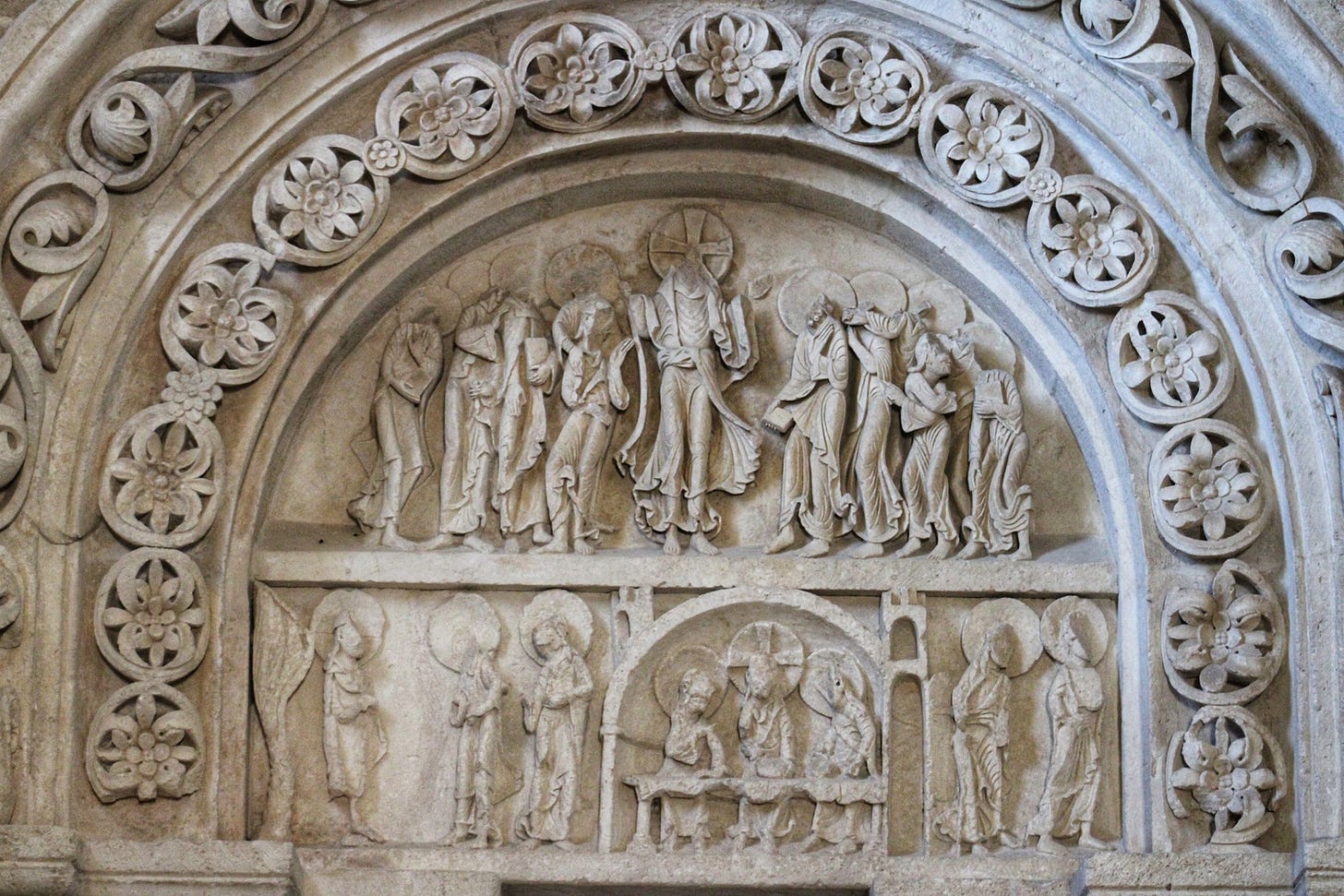

Lower down on the walls, you move into narrative space: scenes from the Life of Christ, feasts, miracles, Passion, and Resurrection. Even lower still, nearer the eye level of the congregation, are images of saints, monks, and martyrs, the Church militant and triumphant, drawing the viewer into communion with God in heaven.

Romanesque and Gothic programmes

So, as we’ve seen, Michelangelo didn’t come up on his own with the idea of depicting the Last Judgment surrounded by the Biblical narrative of salvation. In the West, especially in the Romanesque and Gothic periods, the structure remained theological, but the emphasis shifted from a depiction of cosmic hierarchy to narrative drama. Medieval western churches were decorated more often with sequential story cycles.

And, while the external walls of Byzantine churches were usually quite plain, we moved on to decorating the outside as well. Symbolic theological programmes were now seen on façades and tympana (e.g. Last Judgment at Autun or Chartres), along nave walls as fresco or stained-glass cycles of the life of Christ or Mary or a saint to whom the church was dedicated.

In an essay on understanding iconographic type art, the Kahn Academy points out that you have to already know the story to understand icons. It “involves understanding the specific culturally constructed symbols and motifs in a work of art that can help us to identify the subject matter. To understand the symbols, you have to be familiar with their culturally specific meaning - as in, you need to be ‘in the know’ about agreed-upon conventions.”

So no, these programmes weren’t “medieval picture books” for the unlettered. They were intricate and sophisticated visual theologies for a people who already knew the stories and came to see them made manifest. The iconographic programme was contemplative, participatory and above all, liturgical. It wasn’t there to teach in the ignorant in the modern sense, but to draw the viewer upward into the mystery being depicted.

In this week’s post for paid subscribers, we’ll stick with our Italo-Byzantine thread and discuss how such images were especially integrated into monastic life, and how the iconoclastic crisis of Byzantium brought monasticism more firmly into the west.

So glad you are back and giving us great material, as usual!.

Some other notes about the locations of icons:

The Dormition (Assumption in the West) of Mary is usually on the western wall of the church so you see it as you depart. It is the coda to the biblical narrative of the other icons. Certain other icons are nearly always facing each other. Fr. Hopko (of blessed memory) explains a bit more here: https://www.ancientfaith.com/podcasts/hopko/icons_and_their_placement/