Join us below the fold today as we explore the remarkably long-lived Greek Colony of southern Italy, originally established in the Archaic Greek era, that gave rise to the Greco-Italian culture of modern day Puglia, Sicily and Calabria, including still-existing Byzantine Christian communities.

Magna Graecia

We are so accustomed to look on Italy as one land that perhaps we forget what any map of Europe will show – namely, how near the south of Italy is to Greek lands across the water. The cities of the east coast of Italy, at any rate, are much nearer to Macedonia and Epirus than they are to Rome.

Adrian Fortescue

Especially in our time, when European history seems simply no longer to be taught, it’s easy to forget that “Italy” used to refer only to the geographic landmass of the peninsula. Until 1870 there was no Italian “nation state” in the modern sense at all. There was a patchwork of kingdoms, duchies, republics, city-states and papal territories, each with its own customs, rulers and often languages. The idea of Italy as a unified political and cultural entity is a modern invention, and was brought about by violent conquest.

Long before Rome, the Greeks were here as colonists. In fact, much of southern Italy and Sicily was once known as Magna Graecia, “Greater Greece.” Taranto was founded by settlers from Sparta, Crotone and Sybaris by Achaeans, and Syracuse by Corinthians. These cities were Greek in language, religion, architecture and art, but they were never politically unified, either with one another or with the cities of the Greek mainland.

Of course, a salubrious climate, abundant coastline and fertile soil will always attract human settlement. But the Greek city-states of the 8th to 6th centuries BC had more specific reasons for looking west. Much of the Greek mainland was becoming overpopulated, with agricultural land no longer sufficient for the numbers. Establishing colonies in places like southern Italy and Sicily offered access to fertile land, metals and maritime trade networks, while also relieving political and demographic pressure at home.

But these colonies were not outposts of a unified empire. They became independent city-states in their own right, maintaining strong cultural ties to their mother cities but governing themselves and flourishing on local terms.

After the conquest of the entire Italian peninsula by the Romans, Greek language and culture were allowed to continue in the area under Roman imperial administration.

In this week’s post for paid subscribers, we’re filling in the historical gap between the establishment of the so-called barbarian kingdom of the Ostrogoths in Italy in 476 and the 6th century reassertion of Byzantine rule in Italy that would give rise to the great imperial mosaics at Ravenna.

We’ll stay in the south for now, and look at how the reintroduction of Eastern Roman authority helped shape the sacred art and monastic culture of Byzantine and later medieval Italy. We’ll look at some of these works of art, and talk about how the long survival of a coherent Byzantine culture in the south contributed to a greater visual and perhaps theological coherence in sacred art over the centuries than can be found in the other, Latin parts of Italy.

At The Sacred Images Project, we explore Christian life, thought, history, and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. This work is entirely reader-supported. No ads, no algorithms, just careful research and thoughtful analysis, made possible by your subscriptions.

Free subscribers receive a weekly article uncovering the treasures of Christian tradition. Paid subscribers ($9/month) receive a second weekly piece, plus bonus posts with high-resolution images, video explorations and more.

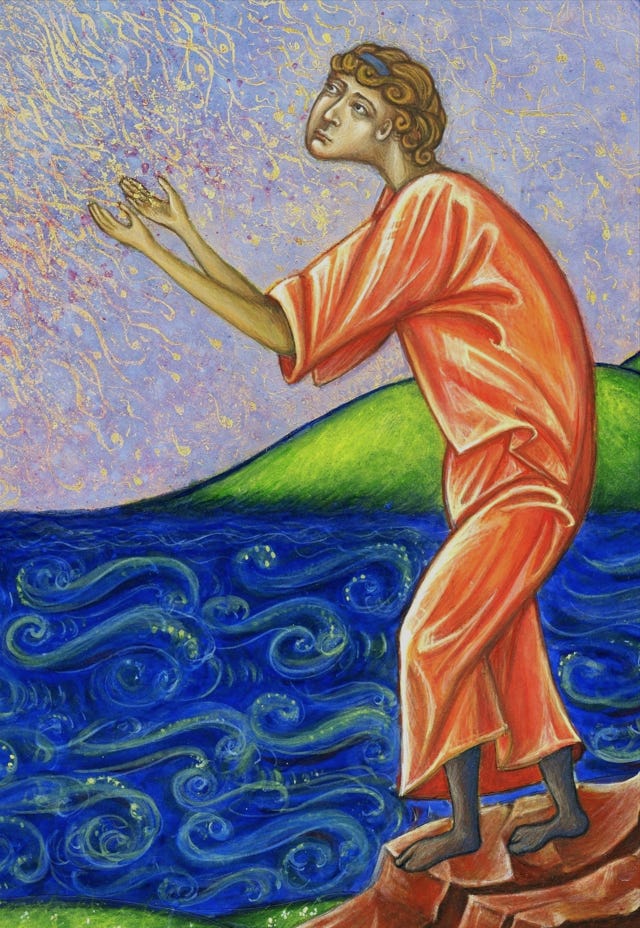

I’m happy to offer prints of this little figure, part of a painting - egg tempera and gold leaf - I did for a client in the contemporary Byzantine iconographic style. He is the speaker in Psalm 84, Quam Dilecta: “My soul longeth, yea, even fainteth for the courts of the Lord: my heart and my flesh crieth out for the living God.”

If you’d prefer to set up a monthly contribution in an amount of your choice, you can also do that at the studio blog, or make a one-off donation to help keep this work going. If you subscribe through my personal page, I’ll add you as a complimentary subscriber here. And thank you.

I hope you’ll join us: