The Only Way Out Is Through: Two Early Medieval Last Judgments

Torcello and Formis: Walking inside Christian Eschatology

Why is it that in some ancient European churches, the most terrifying images in Christian doctrine are the last thing you see on your way out?

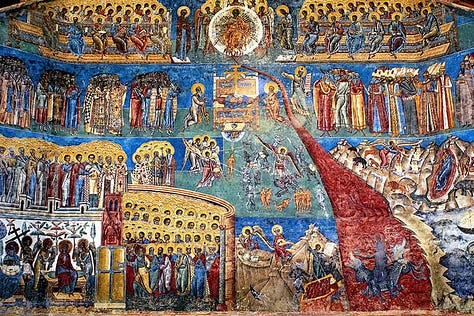

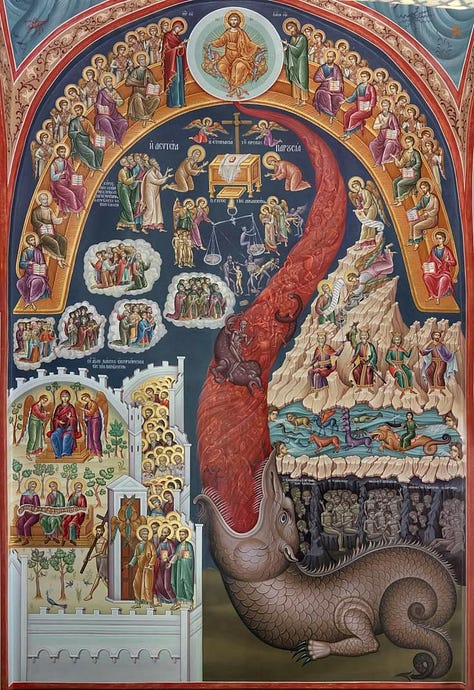

After the Mass has ended, after Communion, after the final blessing, you’re leaving and you are confronted with the most fearsome images in all Christian art. Not Christ in the manger or the Good Shepherd or the Child in the arms of His mother. But Christ in judgment, seated in glory, flanked by angels, weighing souls, separating the sheep from the goats, with a river of fire descending from the throne of heaven straight down to hell.

In last week’s post for all subscribers, we talked about the iconographic programmes; the carefully planned cycles of images in fresco or mosaic, that covered all the surfaces of the interiors of Byzantine and western early medieval churches. These cycles structured how sacred images were arranged to tell the story of salvation, that would have been understood by worshippers, transforming the space inside the church into an elevated, sanctified place where those realities were made present.

In many churches, all the way up to the late Gothic (or “proto-Renaissance”), a typical feature of these programmes was the back wall of the church - the opposite end of the nave from the sanctuary, or the west wall - being decorated with often shocking and arresting images of the Last Judgment. This was an innovation that came to Western Christendom during the 11th and 12th centuries.

In today’s post for all subscribers, we’ll look closely at three examples of these commanding scenes, starting in the period when Italo-Byzantine was established throughout the Italian peninsula and was beginning to merge into the Romanesque style. We’ll look at Torcello’s Basilica of Santa Maria Assunta, a mid-11th century grand, multi-tier mosaic cycle and Sant’Angelo in Formis (Capua) early 12th c. where Romanesque style first appeared. We’ll briefly compare these antecedents to the great fresco of the Arena Chapel in Padua, where Giotto took the motif and translated it into his more naturalistic style.

Today I’m also adding a short paywalled section at the end, where members who want to do a much deeper dive, can find some free downloadable materials related to this post. Specifically, this includes the full text (504 pages) of a 2020 PhD thesis by University of Winchester researcher Patrick Martin, titled “Understanding the Last Judgement Mosaic at Torcello, Venice”. It’s been made freely available through the university’s public repository; with a table of contents that makes it possible to separate and print out sections of particular interest.

If you’re enjoying these deep dives into sacred art history and want to support this work, and receive extras like pdfs, high-resolution image downloads and upcoming course materials, I hope you’ll consider becoming a paid subscriber.

At The Sacred Images Project, we explore Christian life, thought, history, and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. This publication is entirely supported by readers — no ads, pop-ups or distractions — just thoughtful work, funded by your subscriptions.

While The Sacred Images Project has grown into my full-time work, we're now building toward an even richer, multi-layered platform, with plans for e-books, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts and more. Your support helps make this expansion possible.

If you’d like to follow along, you can subscribe for free and receive a weekly article exploring the treasures of Christian history, culture, and sacred art..

Paid subscribers ($9/month) receive a second, in-depth article each week, plus additional exclusive posts featuring in-person explorations, high-resolution downloadable images and more.

If you believe in the importance of preserving and deepening our sacred patrimony, I hope you’ll consider becoming a subscriber today.

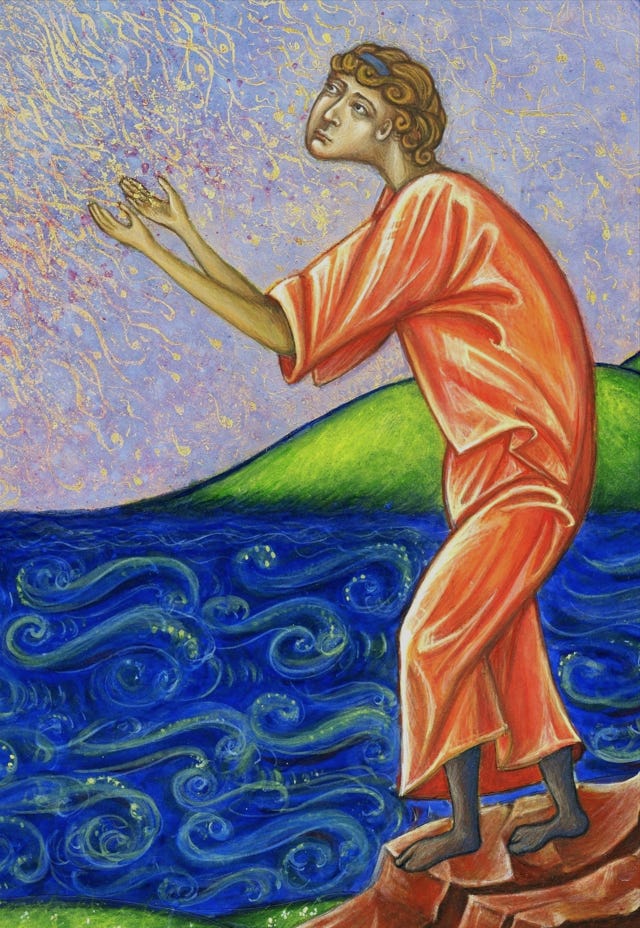

I’m happy to offer prints of this little figure, part of a painting - egg tempera and gold leaf - I did for a client in the contemporary Byzantine iconographic style. He is the speaker in Psalm 84, Quam Dilecta: “My soul longeth, yea, even fainteth for the courts of the Lord: my heart and my flesh crieth out for the living God.”

If you’d prefer to set up a monthly contribution in an amount of your choice, you can also do that at the studio blog, or make a one-off donation to help keep this work going. If you subscribe through my personal page, I’ll add you as a complimentary subscriber here. And thank you.

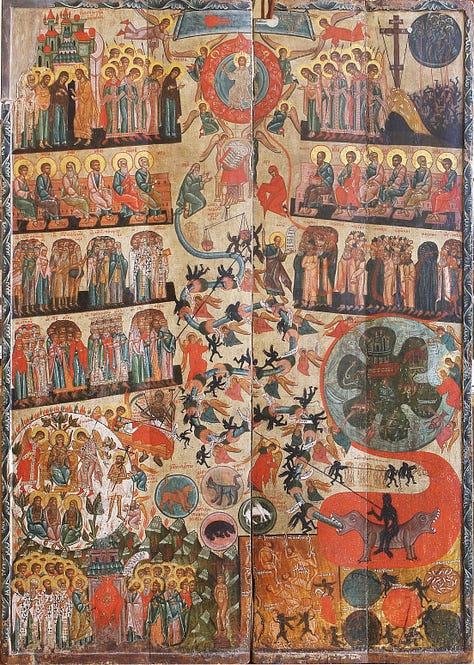

Torcello - a Byzantine vision of the End

Imagine yourself in the 11th century, and you are faced with a monumental and terrifying image: Christ in Judgment, the heavenly host blasting trumpets to call the dead from their graves, a river of fire coursing down from the heavenly throne and pouring into hell to torment the damned, demons and monsters dragging these betrayers of Christ to their unimaginably horrific eternity. What would all that mean to the medieval mind?

The dedication of the entire west wall to these immense mosaic and fresco images of the Last Judgment, appeared in the west in the 11th century, as a theological-artistic innovation and visual strategy of moral reform. In the Byzantine East, the Last Judgment appeared more commonly in funerary chapels, and in the narthex (the entry space or porch) of the church, that you would see before entering the sacred mysteries.

In the east it was more common to find the Dormition of the Virgin on the interior west wall as you go out, invoking a peaceful transition through death and the hope of resurrection. But in the Latin West, after standing at the foot of the altar where heaven and earth had mingled, the faithful were sent back into the world beneath the gaze of Christ the just judge.

The Torcello duomo, the basilica of Santa Maria Assunta, was dedicated in 1008. Though there is no direct record about the commissioning of the mosaic, stylistic and archaeological data suggest it was created in the second half of the eleventh century.

Scholars are divided over who exactly created it but opinions lean toward it being Byzantine, with the artisans directly brought up from Constantinople. Analysis of the Torcello tesserae indicates the raw glass was probably imported from Syria.

This fits with the political and economic priorities of Venice at the time, trying to create stronger ties with Constantinople (soon to be burst asunder forever by the Sack of Constantinople by western Crusaders.)

Patrick Martin, in his PhD thesis on the Torcello mosaics, wrote that this Last Judgment mosaic is significant as a work of visual theology, for its reconciling of “apparently inconsistent” Christian doctrines on the fate of souls. Using an eastern concept of time, he says, the mosaic cycle depicts the unity of the concepts of the Last Judgment and the individual’s Particular Judgment, showing Christ being outside the constraints of natural time.

“While the Western iconography sets the Last Judgment in the future and ignores the Immediate [‘particular’] Judgement, the Byzantine format unites both within a continuous present. The analysis shows how the mosaicists at Torcello combined this concept of time with strong visual guidance to deliver a clear structure and a single, complete, and coherent eschatological vision.”

Martin argues that the Torcello mosaic was intended to provoke spiritual reflection and moral responsibility in viewers, not just to awe them visually. It’s a liturgical and theological statement that functions as an integral part of the liturgical actions, in the Byzantine manner.

We’ve had a brief introductory look at the Torcello mosaics from my trip up there last February, which you can read here (with a subscription.)

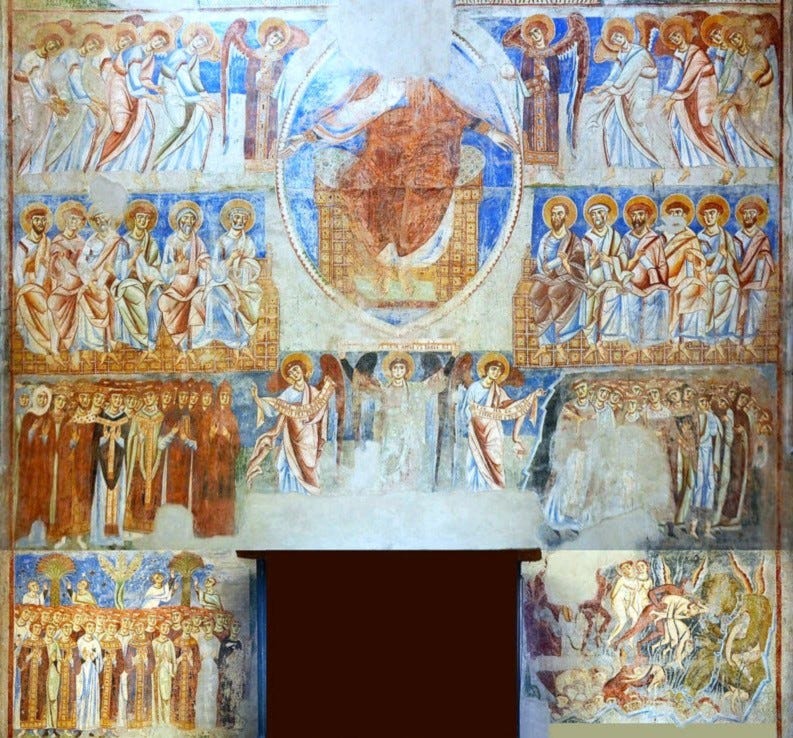

Sant’Angelo in Formis - when Italo-Byzantine became Romanesque

If there is one church in Italy that can be said to be the birthplace of the formal Romanesque painting style, it might be the abbey of Sant’Angelo in Formis, on Monte Tifata near Capua in southern Italy. It was rebuilt in the mid-11th century under the direction of Abbot Desiderius of Monte Cassino, who later became Pope Victor III. The abbot commissioned artisans from Constantinople to create a cycle of frescos in a style showing a marked movement away from strict Byzantine forms and into something new.

The church was part of the broader Benedictine revival linked to Cluniac reform, and its wall paintings reflect this renewed emphasis on liturgical clarity, theological instruction, and monastic culture.

Read more about the rescue of western Christendom by the Cluniac revival of monasticism, here:

The frescoes fuse Constantinopolitan stylistic and iconographic models with Latin pastoral and doctrinal aims.

The most striking of these paintings, though not well preserved, is the full-wall fresco of the Last Judgement on the church’s west wall, directly opposite the sanctuary. This vast and commanding composition is the earliest surviving instance of the Romanesque Last Judgement scheme in monumental wall form. At the top sits Christ in Majesty, enthroned on a rainbow within a radiant mandorla - images from the Book of Revelation and the vision of Ezekiel.

He is flanked by the court of angels and the Apostles reigning in glory.

The next levels below this heavenly court are in registers: angels with trumpets summon the dead, souls rise from their tombs, and the dread words of the just Judge are announced on scrolls by His angels, either a glorious welcome or terrible condemnation. The blessed are led toward Paradise, while the damned are dragged toward a vividly depicted Hell.

This west-wall fresco at Formis set the visual template for what would become standard forms across Romanesque Europe. Though the iconographic roots lie in Byzantine apocalyptic art, the scale, placement and didactic force of the images reflect a distinctively Western concern with moral accountability.

Sant’Angelo in Formis marks the threshold of a new visual era: a bridge between Eastern theological tradition and the emerging Latin Christian world of the 11th and 12th centuries.

Christ in Majesty

The central and defining element of nearly all Last Judgement scenes in both Byzantine and Western medieval art is the image of Christ in Majesty, a variation on the Pantocrator. Seated on a throne, often a rainbow in Last Judgment scenes, within an almond-shaped mandorla that shows the breaking-through of Christ from heaven into this world. Christ appears in His full divine authority as Judge and ruler of the living and the dead, all of heaven, earth and hell.

This is not the sympathetic suffering Christ of the Passion or the humble infant of the Nativity, or the teacher and miracle worker of the Gospels. This is the exalted Lord, in absolute glory at the end of time as seen in the ecstatic visions of the prophets Daniel and Ezekiel, and the Apocalypse of St. John.

His right hand is typically raised in blessing, while his left often holds a scroll or closed book representing the divine law, the Book of Life or the Gospels. He is often surrounded by the Tetramorphs, the symbolic figures of the four Evangelists. The pose is symmetrical, frontal, monumental and hieratic, illustrating His unchallengeable authority.

The visual type of Christ in Majesty developed early in Christian art, with strong roots in Roman imperial portraiture.

A River of Fire - divine love an unbearable torment for the damned

Every man's work shall be manifest; for the day of the Lord shall declare it, because it shall be revealed in fire; and the fire shall try every man's work, of what sort it is. If any man's work abide, which he hath built thereupon, he shall receive a reward. If any man's work burn, he shall suffer loss; but he himself shall be saved, yet so as by fire.

1 Corinthians 3:13–15

In one of the strangest Christian teachings commonly translated into visual language, a river of divine love flows like a river of fire from Christ’s throne, ending in hell where it is the principal source of torment for the damned.

This motif is found in Scripture, elucidated by the Church Fathers, and is repeated in most Byzantine and western medieval depictions of this kind.

The same divine love that fills the hearts of the blessed with joy, fills the damned with despair and hatred.

Love will enrobe everything with its sacred Fire which will flow like a river from the throne of God and will irrigate paradise. But this same river of Love - for those who have hate in their hearts - will suffocate and burn.

“For our God is a consuming fire”, (Heb. 12:29). The very fire which purifies gold, also consumes wood. Precious metals shine in it like the sun, rubbish burns with black smoke. All are in the same fire of Love. Some shine and others become black and dark. In the same furnace steel shines like the sun, whereas clay turns dark and is hardened like stone. The difference is in man, not in God. - Dr. Alexander Kalomiros

“We all receive God’s blessings equally. But some of us, receiving God’s fire, that is, His word, become soft like beeswax, while the others like clay become hard as stone. And if we do not want Him, He does not force any of us, but like the sun He sends His rays and illuminates the whole world, and he who wants to see Him, sees Him, whereas the one who does not want to see Him, is not forced by Him.” St. Peter Damascene. Philokalia, vol. 3, p. 8.

These standardised forms of depicting the Last Judgment were never meant to be a matter for mere natural curiosity, still less a piece of horror for frightening people into unwilling obedience. This is a visual immersion into eternal truths, and a call for honest self-examination, placed at the threshold between the sacred world of the liturgy and our return to secular life. The people who made it and who saw it every day, believed that our choices in life have eternal consequences.

In the mosaic at Torcello, the iconographic language is not only grand and terrifying but ordered, structured and liturgical, offering the viewer a vision of justice that is ultimately rooted in the mystery of divine love. The fire that pours from the throne of Christ is not wrath but glory; the same love sanctifies the saints and burns the damned. What distinguishes their fate is not the nature of God, but their own readiness to receive Him.

These monumental images, then, are expressions of a culture embedded in faith, that took the fate of souls seriously.

I hope you enjoyed this deep visual dive into the meaning of these grand and timeless spiritual images.

Below this paywall, paid subscribers will find some downloadable high resolution images and the full text of Dr. Patrick Martin’s book on the deeper meanings of Torcello’s mosaics.

I hope you’ll join us: