To venerate is to draw near: monastic art and the desire for communion

Seeing "with the nous," the eyes of the soul

Drawn into a larger world

People are drawn to honour these images with the offering of incense and lights, as was piously established by ancient custom. Indeed, the honour paid to an image traverses it, reaching the model, and he who venerates the image, venerates the person represented in that image.

Second Council of Nicaea, 787

This short statement from the Seventh Ecumenical Council, Nicaea II, cuts to the heart of why Christian sacred art matters and why so many of us feel instinctively drawn to it. It’s not about sentiment or personal aesthetic preference. And it's definitely not any superficial nostalgia for a lost style. It’s about a theological and spiritual reality: when we venerate a sacred image, we are not admiring a picture, we are reaching toward a Person, and a whole perfected, joyous universe of reality beyond our ordinary perceptions.

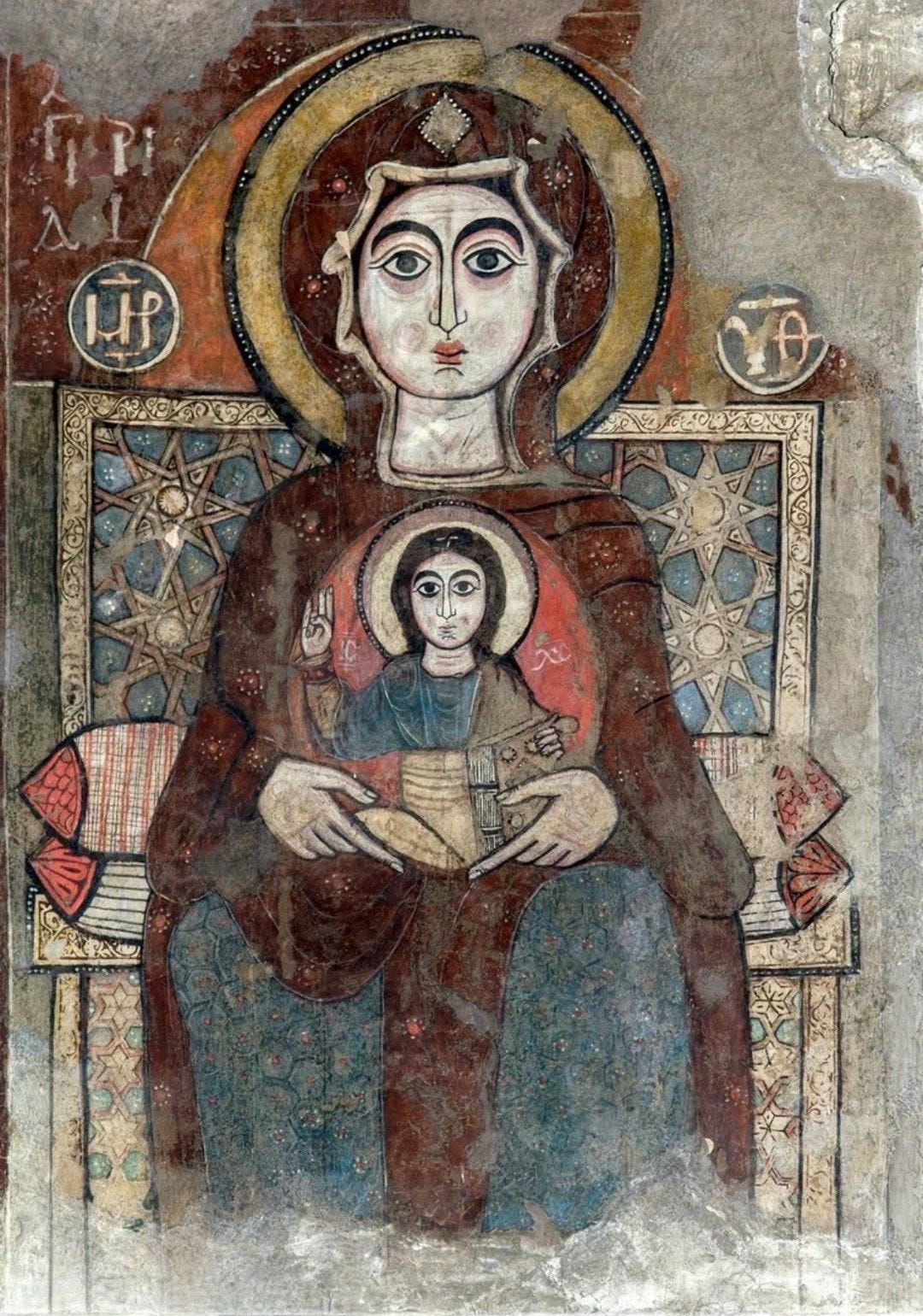

It’s not always easy to explain why ancient Christian art moves me so deeply, especially the kind of art that looks at first glance rough or strange. Visually, these works are often difficult: the eyes are too big, the hands too long, the proportions are weird, the colours are faded, the forms abstracted and obscure and the visual language has often become indecipherable over the great expanses of time. But I am compelled nonetheless; the more I look, the more I find I want to keep looking.

For many of us, especially those who feel spiritually out of sync with the modern world, there can be something irresistible in the sacred images of the early centuries of Christianity.

In today’s post for paid subscribers, we explore why ancient Christian sacred art, especially the stark, powerful images of early Coptic and European Romanesque monasticism, still draws so many of us so deeply. Rooted in the theology of the Second Council of Nicaea and the writings of St. John of Damascus, these icons were never meant to illustrate ideas or decorate spaces, still less to imitate mere nature as seen by the physical eye. They were created for something far more intimate and transformative: spiritual communion with the Prototype, through the sanctified perception of the nous, the “eye of the soul” - a spiritual faculty we in the west have largely forgotten. If you’ve ever found yourself gazing into an ancient icon and feeling, somehow, seen, this is for you.

I hope you’ll subscribe to join this conversation.