A Christian Kingdom No One Talks About

People interested in history will have heard the name “Visigoths,” but probably associate it mostly with the “barbarian invasions” that wrecked the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century. But who were they, really, and what happened to them?

In the standard classroom version of history in which the Visigoths tend to appear, they helped Alaric sack Rome in 410 and then faded from the story like a storm that passed through. But in reality, they didn’t vanish. They converted to orthodox Nicene Christianity (eventually), settled, governed and for over a century and a half built a Christian kingdom in Spain, one that developed its own liturgy, theology and sacred aesthetic.

That kingdom, once powerful enough to host ecumenical councils and produce some of the finest goldsmithing in post-Roman Europe, collapsed almost overnight in 711, when Muslim armies crossed the Strait of Gibraltar and defeated the last Visigothic king. The Christian kingdom of Spain disappeared, and its remnants and refugees fled.

In today’s post for all subscribers, we’re turning west - far west - to explore what happened to Christian sacred art in Visigothic Spain.

This often-overlooked kingdom, briefly powerful, deeply Christian and artistically distinct, was building its own sacred culture when it was suddenly extinguished.

Before that moment, Spain had its own councils, its own churches, its own treasures offered in gold and stone. It even had a court and legal culture shaped by theology. And then, in the space of a few years, it was all gone.

At the Sacred Images Project we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. The publication is supported by subscriptions, so apart from plugging my shop, there is no advertising or pop-ups. It’s my full time job, and while it’s now providing me with a full time income, we are now looking at growing this into a multi-layered, multi-media project, so I can’t yet provide all the things I want to and am planning for.

You can subscribe for free to get one a week.

For $9/month you also get a second, weekly paywalled in-depth article tracing the history and meaning of our great sacred patrimony. For paid subscribers there are also extra posts with in-person explorations, exclusive photos and videos and materials like downloadable exclusive high resolution printable images. In the works are ebooks, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts.

From the shop: I’m happy to offer this drawing of the Crucified Christ, “Christus Patiens” that I did in the style of the 14th century Umbrian panel crucifixes. It’s printed on the same museum quality 100% cotton, acid-free paper I drew it on.

Browse the shop here:

If you’d prefer to set up a monthly contribution in an amount of your choice, you can also do that at the studio blog, or make a one-off donation to help keep this work going. And thank you.

Something to listen to while you read

Mozarabic chant of Islamic-occupied Christian Spain

By the end of the 7th century, Imperial Rome was a distant memory and Western Europe had splintered into a mosaic of kingdoms. We’ve talked about the Lombards in Italy, the Merovingians in Gaul, and the continuing Eastern influence in Rome and southern Italy, but what about the furthest Mediterranean edge of the old empire? What about Spain?

We might forget that before the coming of Islam, Spain was the centre of a Christian kingdom, ruled not by Romans but by Visigoths who had arrived from eastern Europe in the 4th and 5th centuries. And for a brief time, this Visigothic kingdom had begun to forge a sacred culture of its own: Christian, Latin, and increasingly orthodox (that is, Nicene) Christians.

Then one day, across the narrow strait of Gibraltar came a Muslim force led by Tariq ibn Ziyad, under orders from the Umayyad caliph in Damascus. The Visigoths, fractured by internal rivalries and recent civil war, were unprepared. Five of the 25 kings who ruled between 470 and 710 were assassinated, five were dethroned and five had to face a conspiracy. King Roderic of Spain, last of the Visigothic kings, whose legitimacy was contested even before the invasion, met the army in battle near the Guadalete River.

The exact numbers are unclear, but the result is not. Roderic was defeated and likely killed, his army scattered. In the wake of that loss, the entire kingdom collapsed with breathtaking speed. Within three years, nearly the whole of the Iberian Peninsula was under Muslim rule.

Some cities capitulated, some were taken by force. Many bishops and monastic communities fled north, into the mountains of Asturias or across the Pyrenees into Frankish territory. Others stayed and negotiated new terms, accepting dhimmi status and continuing to worship - under surveillance and constraint - in what would become known as Mozarabic communities.

Visigothic churches were converted into mosques. Others were abandoned or destroyed. Much of the kingdom’s sacred art vanished, either repurposed or lost. Even the famous Guarrazar crowns were likely buried during this time to protect them from looting. They were never recovered by their owners.

The Visigoths Convert

The Visigoths entered Spain as Arian Christians, followers of one of the early Christological heresies that denied the full divinity of Christ, conquering the existing Hispano-Roman population and finally creating a new lawcode that treated Roman and Gothic citizens equally. In 589 AD, at the Third Council of Toledo, King Reccared I publicly renounced Arianism and embraced Nicene orthodoxy. This was more than a political move, it brought the kingdom into full communion with the wider Church and opened the door for a flourishing of Christian life and sacred art.

Under Visigothic rule, bishops wielded enormous social and legal influence, and councils of Toledo met regularly to debate both theological and civic questions. It was under the Visigothic kings that Europeans were first introduced to the notion of a sacred monarchy, under the doctrine of bishop St. Isidore of Seville, the leader of the fourth council of Toledo and the most significant writer of the kingdom.

The political importance for the rest of early medieval Europe of the consolidation and sacralization of the Visigothic royalty persisted even after the fall of the Iberian Peninsula. Rulers of the Christian kingdoms would trace their ancestry back to the Visigothic kings in order to legitimate their power during the political instability from the 8th to the 10th century.

It was a time of tightening unity between Church and state - a Christian kingdom trying to find its voice in a larger Christian world.

Visigothic Art and Architecture

Visigothic art is often overlooked, partly because so little of it survives. But what remains gives us tantalising glimpses of a distinct sacred aesthetic that blended late Roman forms and Germanic motifs, and began to develop something new.

Churches like San Juan de Baños (founded c. 661) feature horseshoe arches, a form that would later become a hallmark of Islamic architecture in Spain. The Treasure of Guarrazar, a set of votive crowns offered by Visigothic kings, shows a fusion of courtly luxury and Christian devotion. In stonework and carving, we see a preference for interlace patterns, inscribed crosses, and bold symbolic forms, not yet figural, but deeply charged.

This wasn’t a culture of icons yet, but it was one that understood sacred space, sacred offering and the power of symbols.

What is “Mozarabic” Christianity?

Then, in 711 AD, everything changed. Tariq ibn Ziyad’s army, on the orders of the Caliph in Damascus, crossed the Strait of Gibraltar and within a few years, almost the entire Iberian peninsula was under Islamic control.

The Visigothic elite vanished. Churches were converted or destroyed. Artisans, many monastics, adapted or fled. For the Christians who remained, their faith survived under new terms: they became Mozarabs, Latin-speaking Christians under Muslim rule, a word derived from the Arabic mustaʿrib, meaning “those who became Arabised.” Their culture filtered through Arabic aesthetics and restrictions on figural art. Christian Europe was shocked that an entire Christian kingdom was swept away almost overnight.

As dhimmis, non-Muslims under Islamic governance, Mozarabs were legally protected but clearly second-class citizens. They were required to pay a special tax, the “jizya,” excluded from public office and their legal rights were limited, especially in disputes involving Muslims. They could not build new churches or openly repair old ones without special permission and public expressions of Christian faith such as processions, bell ringing, or visible crosses were often forbidden. Christians were sometimes made to wear distinctive clothing, keep their churches lower than mosques and yield the way in public as a sign of deference.

Despite these humiliations, Mozarabs endured. They worshipped quietly, preserved their ancient liturgy and continued to create. The churches they built in exile and the chants they sang bear witness to a Christianity that survived not by hiding, but by adapting and remembering.

Northern Kingdom of Christian Refugees - Asturias

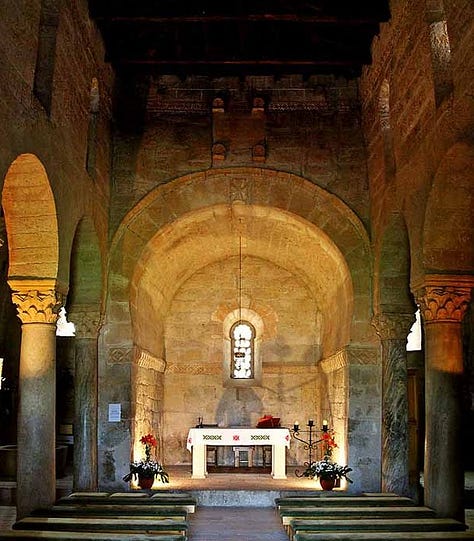

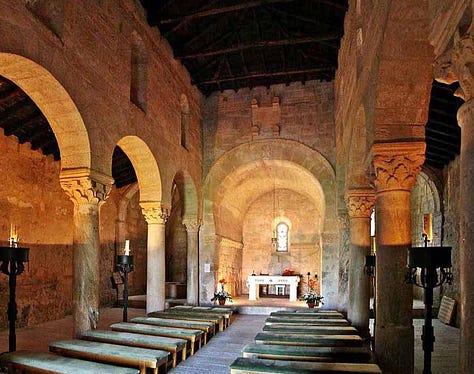

Some Mozarabic Christians fled to the Christian-controlled territories of the north, bringing with them memories of their former cities and sacred traditions. There, in the new frontier kingdoms of León and Asturias, they began to build churches again that retained the distinctive forms of Visigothic sacred architecture.

The monastery of San Miguel de Escalada, constructed in 913 by monks who had migrated from “al-Andalus,” is a particularly striking example. The horseshoe arch, often wrongly attributed to Islamic architecture as an original innovation, has deep pre-Islamic roots in Christian Spain.

The Beatus Manuscripts

It was in this monastery that the Mozarabic imagination found one of its most striking outlets in the person of the monk Beatus of Liébana (c. 730 – c. 785) who compiled a commentary on the Apocalypse in the late 8th century, produced some of the most visually arresting Christian manuscripts of the early Middle Ages, launching a whole genre of early medieval manuscript illustration.

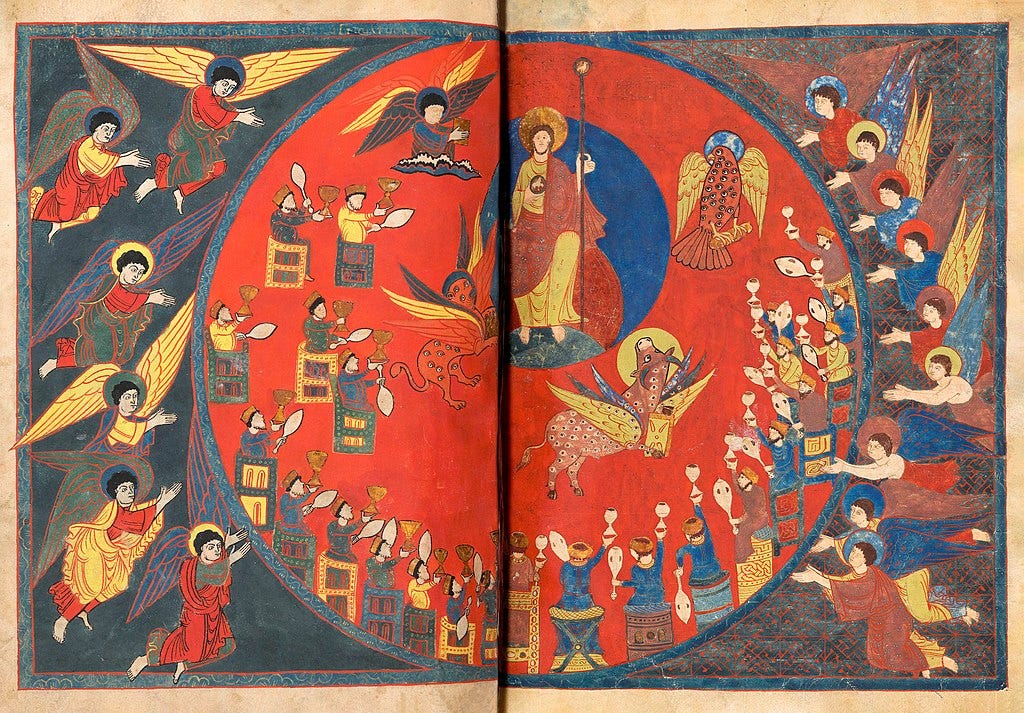

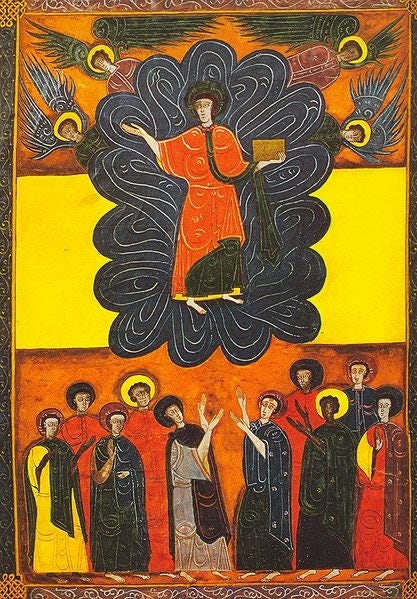

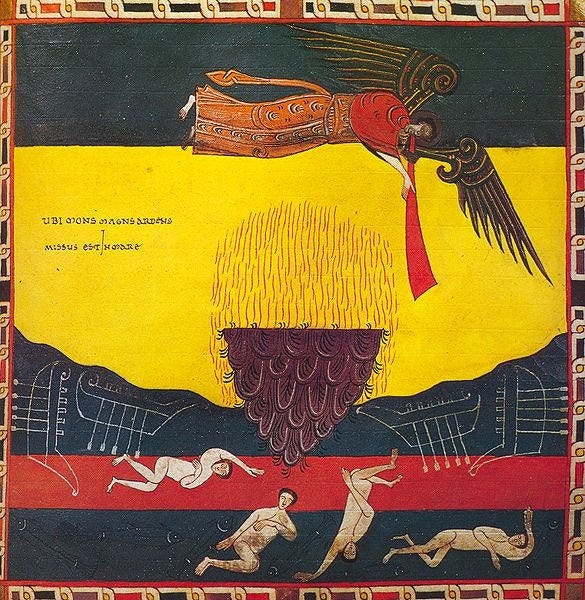

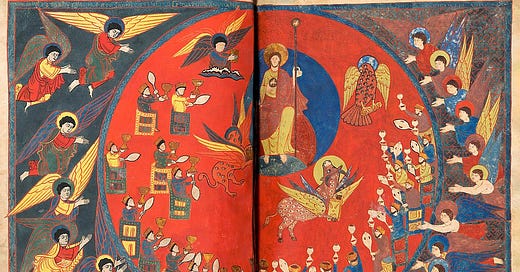

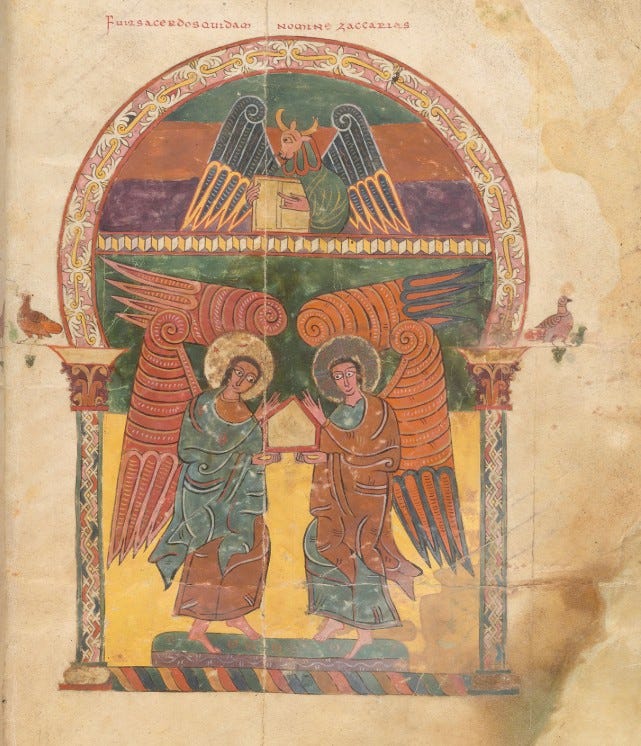

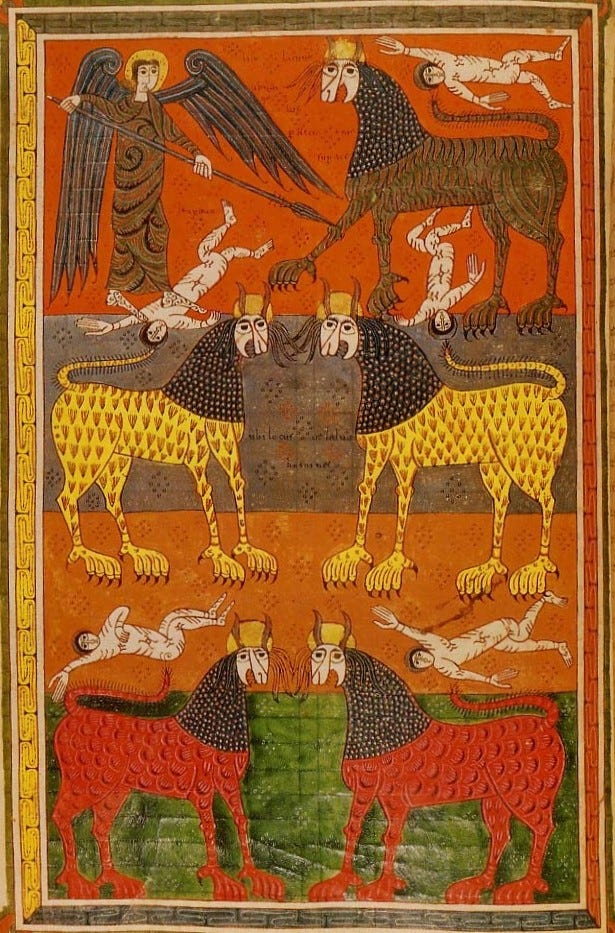

Over the next three centuries, illuminated copies of the Beatus text were produced in monastic scriptoria across northern Spain, in Mozarabic, post-Visigothic communities. These manuscripts, now known collectively as the Beatus manuscripts, became a distinctive visual tradition: bold, symbolic, and apocalyptic, expressing the cosmic drama of Revelation in vivid colour and stylised forms.

Characterised by flattened perspective, saturated reds, blues and golds laid down in flat fields with no attempt at shading or naturalism, and figures with wide staring eyes and dramatic gestures. Human figures are elongated and stylised; Angels, fantastic chimeric beasts, cities and saints are rendered in dense, almost surreal compositions that blend Christian iconography with repeating geometric decorative motifs typical of pre-Islamic Visigothic art.

The tradition spread beyond Spain, into France; dozens of surviving examples from the 10th and 11th centuries survive, preserve a vibrant, symbol-rich style. Together, these manuscripts preserve a deeply theological and intensely imaginative form of sacred art, born in exile, shaped by liturgy and sustained by a Christian culture under siege.

There is an arresting sense of urgency in these images, as if the artists, perched on the edge of a collapsing world, were trying to make visible the truths that history was threatening to erase. And perhaps they were. The Beatus manuscripts were not just biblical commentary; they were visual expressions of eschatological hope.

Mozarabic culture matters not only because it represents continuity, but because it reveals something deeper about the nature of sacred art: its ability to persist, to adapt and to express the faith even under pressure. In the architecture of exiled monks, in the strange and vivid pages of apocalyptic manuscripts and in the rhythms of a liturgy shaped by centuries of devotion, we find a Christianity that did not collapse in the face of conquest.

Fun fact: in the war against the muslim taifas, once It was over and the whole peninsula got rechristianised, the liturgy of Córdoba, as mozarabic as you could get, was snuffed like a candle, and nothing remains. It was even in the 1970s that majority of bishops in the south weren't locals too. Much was lost, as it always is in war, and the Victors did do whatever changes they wanted.

This is thrilling to read, Hilary! I knew nothing of these illuminated manuscripts at all!