What is the Most Ancient of All Illuminated Bible Manuscripts?

Royal Pages: the Mystery and Meaning of the Purple Gospels

The book itself as a treasure

When we think about ancient manuscripts, a whole set of ideas and images and feelings come with them. I don’t remember how old I was when I started wanting one, but it might have been when I read the chapter in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader where Lucy steals into the magician Coriakin’s library and opens his great book of spells. The pages glow and shimmer and come alive, a living book, hand-lettered, ornamented, strange, full of wonders that can’t be found on ordinary paper.

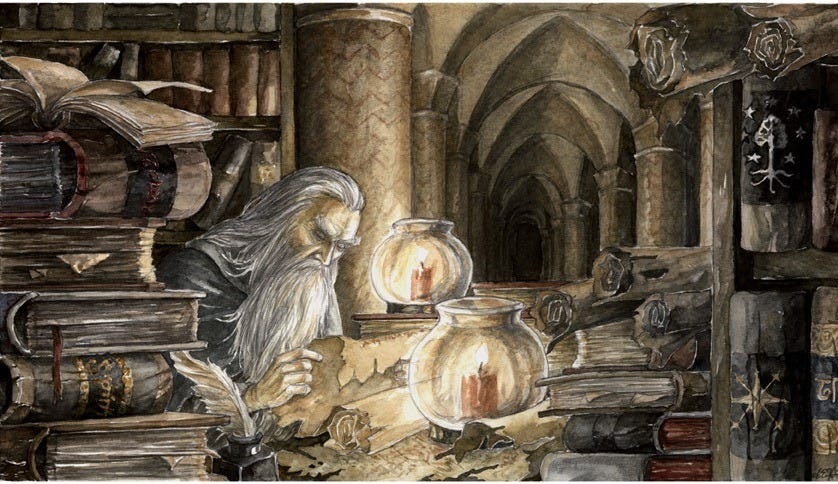

Or maybe it was that brief moment of Gandalf digging through the archives of White City looking for evidence that Isildur had taken and kept the One Ring.

That idea of a manuscript, as an object of wonder itself, has always stuck with me. These wondrous things, made through painstaking and slow processes, hand made ink flowing from a quill pen held in a skilled scribe’s hand. Even the scent of parchment, if you’ve ever handled it, contributes to the effect: this is not anything like our modern, disposable print books on cheap cellulose paper, destined to yellow and finally disintegrate, or to be pulped or tossed into a landfill. These books were made to be treasures, to last a thousand years, to bring the knowledge of our ancient betters into our time, and to be kept with reverence for generations.

There are many different kinds of manuscripts, a whole taxonomy. One type is closely linked to the southern Italian Greek colonies, and takes this sense of the sacred substance of the object and amplifies it to something almost liturgical in itself. These are the purple codices, manuscripts written on parchment pages dyed a deep violet, the colour of the emperors. The writing is done not in black ink, but in silver and gold. They are examples of the book as a relic, a sacred ritual object in itself.

These purple manuscripts, mainly created in the 6th century in the Byzantine world, were never common, even in their own time. They weren’t made for study or reference, or to be copied and passed around. They were rare, precious ceremonial objects made to honour the Word of God itself by clothing it in imperial colours and precious metals.

In today’s post for paid subscribers, we’ll explore these strange and beautiful books that spoke the Gospels in words and through the language of precious metals, colours and sacred craft. They were created in the 6th century in places that are far-flung today, but in their time were just provinces of the empire: Calabria, Syria and Constantinople itself.

We’ll look closely at the few surviving purple codices, who made them and why, what they meant and how they fit into the wider world of early Christian sacred art. If you’ve ever wanted to understand how a book could become an icon, or why early Christians believed the Gospel deserved to be written in gold, subscribe to join us.