When the World Changed: Sacred Art and the coming of Islam

From Byzantium to Britain and the rising shadow

It is the early 7th century, and the old world of the Mediterranean stood on a precipice.

In the East, Byzantium was still reeling from the exhausting and brutal wars against Persia. Great cities had burned. Jerusalem had fallen and been reclaimed. The True Cross had been taken as a trophy of war. Emperors rose and fell with alarming speed. Though the Eastern Roman Empire had survived the onslaught, barely, it was battered, bleeding and brittle.

And yet, despite the chaos, the sacred arts flourished. In Constantinople, the domes of Hagia Sophia shimmered with gold and glass mosaics that captured the uncreated light of heaven. In Ravenna, Christ gazed out from apse and arch with the serene confidence of divine kingship. Processions of saints in jewel-toned robes crossed the walls of sanctuaries like heavenly courtiers. The image of God made visible, incarnate, and triumphant had become the cornerstone of Christian art.

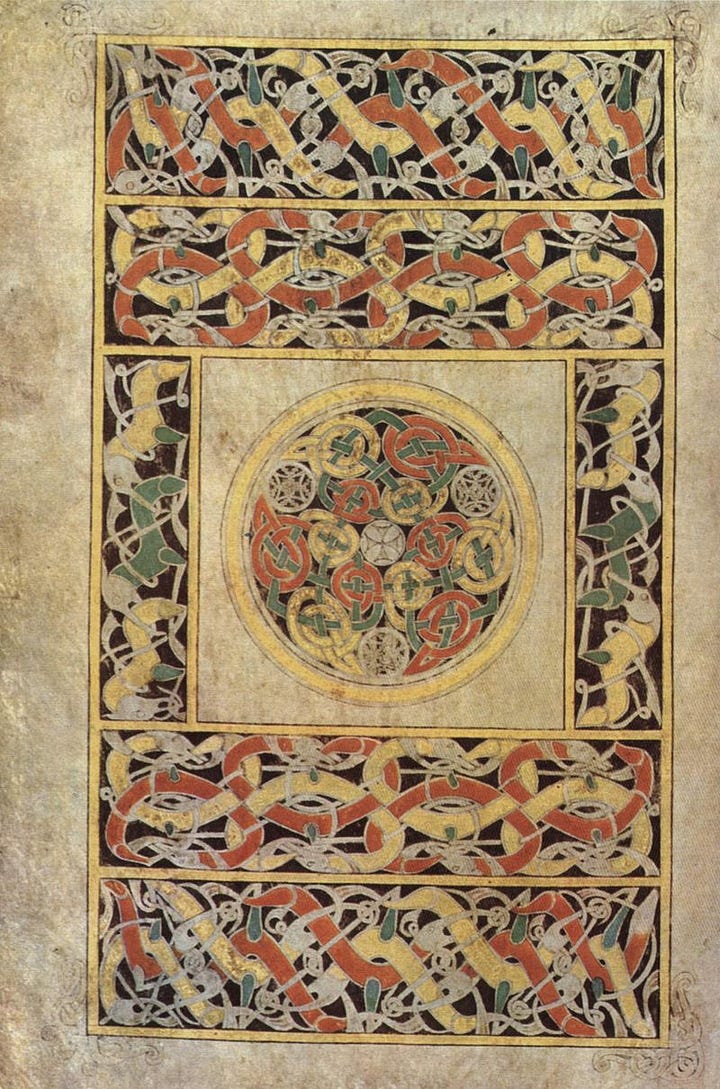

To the west, Britain and Ireland, far from the imperial centres, were stirring with new creative energy. Missionaries and monks were carving a fresh Christian identity into the raw material of a post-Roman world. The Book of Durrow, the Lindisfarne Gospels, and the carved stone crosses of Iona emerged from this wild frontier of the faith, filled with patterns and symbols that spoke of eternity in knots and spirals.

But across the deserts of Arabia, something was stirring, something that would soon cast a long and complex shadow over the entire Christian world.

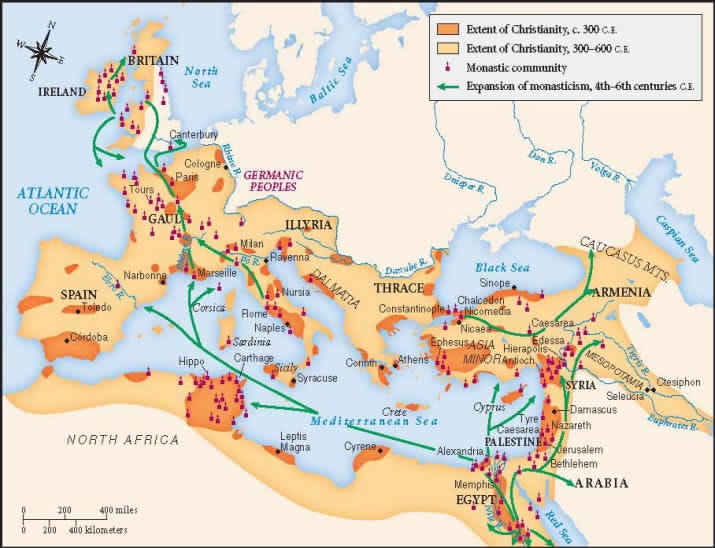

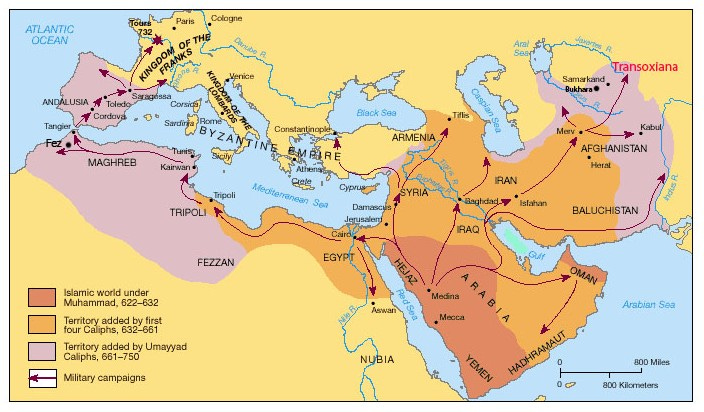

Within a single lifetime, Islam would rise from obscurity and sweep across the old heartlands of Eastern Christianity. Antioch, Damascus, Jerusalem, and Alexandria, centres of theology, pilgrimage, monasticism, and sacred art, would fall under a new religious power. The sea that had been a Christian sea, ringed by basilicas and monastic foundations, would become the heart of an Islamic empire.

The world had changed, and Christian culture would never be the same.

In today’s post for all subscribers, we introduce the second quarter of the year’s Big Editorial Plan, by taking a wide-angle look at the overall situation with the Church and sacred art in the early 7th century. The world of ancient Christianity is coming apart at the seams: Byzantium, still reeling with its war with Persia, is now under siege from a rising Islam that exploded out of the Arabian peninsula, and the old centres of Christian culture are about to fall.

Yet even in this moment of crisis, the art of Christianity does not vanish, it adapts. From the icons of Sinai to the manuscripts of Ireland, from mosaics in Rome to stone crosses in Armenia, the visual language of Christian faith continues to grow. This post sets the stage for what’s to come on the blog this quarter, with a glimpse into the art, architecture, and imagery that emerged when the world changed.

At the Sacred Images Project we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. The publication is supported by subscriptions, so apart from plugging my shop, there is no advertising or pop-ups. It’s my full time job, and while it’s now providing me with a full time income, we are now looking at growing this into a multi-layered, multi-media project, so I can’t yet provide all the things I want to and am planning for.

You can subscribe for free to get one a week.

For $9/month you also get a second, weekly paywalled in-depth article tracing the history and meaning of our great sacred patrimony. For paid subscribers there are also extra posts with in-person explorations, exclusive photos and videos and materials like downloadable exclusive high resolution printable images. In the works are ebooks, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts.

From the shop:

You can click here to order one, or browse the shop:

Christendom in 632: A World on the Edge

It is the middle of the year 632. Muhammad has just died in Arabia, but the Christian world does not yet know that its horizon is about to shift forever.

The Byzantine Empire, battered but proud, stands as the last great heir of Roman imperial power. Her emperor, Heraclius, has just emerged victorious from a long and brutal war with the Sassanid Empire, the last great pre-Islamic Persian dynasty. After years of back-and-forth devastation, he has reclaimed Jerusalem for Christianity and returned the relic of the True Cross in triumph.

There is jubilation in Constantinople, with processions and hymns of thanksgiving. It feels like a new beginning, a miraculous restoration of Christian order. But it is an illusion. The empire is exhausted. The treasury is empty. The army is stretched thin. The people are weary.

Who were the Sassanid Persians?

But that map above of the spread of Christianity doesn’t tell you the whole picture; it was certainly a cross-border religion, but the Christian Roman empire of Constantinople had serious political difficulties. One of the major threats to Imperial Rome in the old days before 313 and Constantine, was still there.

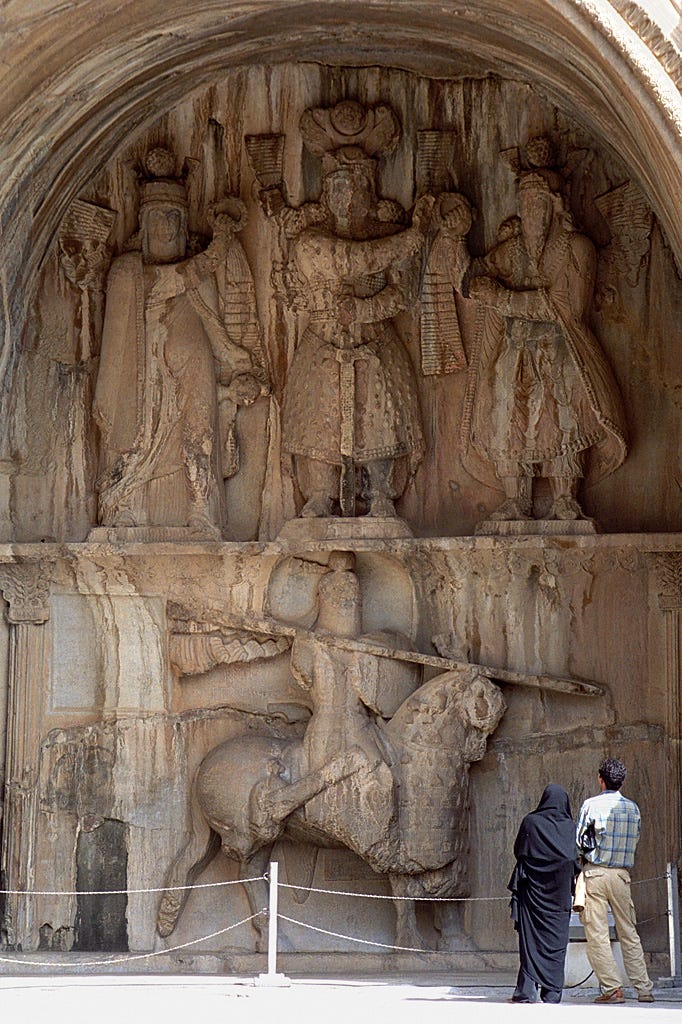

The Persians who battered the Byzantine frontiers in the early 7th century were heirs to one of the most ancient and enduring civilisations in the world. Known as the Sassanid Empire, they ruled from their capital at Ctesiphon, near modern-day Baghdad, and saw themselves not merely as kings, but as custodians of the sacred order, defenders of Zoroastrian beliefs against the chaos of the outside world.

Their empire, stretching from the Euphrates to the Indus, was a rival to Rome in both splendour and ambition. Theirs was a court of fire temples, silk-robed nobles, and monumental reliefs carved into cliffsides, celebrating cosmic kingship and divine favour. Where Rome had emperors, Persia had shahanshahs, “Kings of Kings.”

By the late 6th and early 7th century, this ancient rivalry flared into one final, catastrophic war. Under the formidable King Khosrow II, the Sassanids seized huge swathes of Byzantine territory, including Syria, Palestine, and even Egypt. Jerusalem fell to Persian forces in 614, and with it, the relic of the True Cross was taken into exile, a blow that sent shockwaves throughout Christendom. For a time, it seemed the old empire might crumble entirely.

But then the Byzantines, under Heraclius, mounted a daring counteroffensive.

Between 622 and 628, Heraclius marched deep into Persian territory, even desecrating the great fire temple of Takht-e Soleymān, a city that was sacred to Zoroastrianism and contained one of their most important temples. The Persians, broken and humiliated, overthrew their king.

But the price of victory was exhaustion. Byzantium emerged victorious but weakened beyond measure, and into that vacuum, from the desert, came something neither empire had foreseen.

A new threat from an unsuspected source

In the early 7th century, neither the Byzantines nor the Persians anticipated that a new religious force would emerge from the deserts of Arabia. The inhospitable region had long been peripheral, important for trade and tribal alliances but not for empire-building.

Before Islam, the Arabian Peninsula was a politically fragmented and culturally diverse region, lying on the periphery of the great empires of Byzantium and Persia. There was no central authority or unified kingdom governing Arabia as a whole. Instead, the peninsula was dominated by independent tribes, often in conflict with one another, and loosely organised through kinship and clan structures.

That changed rapidly after 610, when Muhammad began preaching in Mecca. Within a generation, the Arab tribes were united under Islam and launched a swift and effective military expansion. Christians only held their homelands for a few years. Damascus fell in 635, Jerusalem in 638, and Alexandria in 642. The Islamic conquests swept across the Christian heartlands of the eastern Mediterranean, claiming much of Syria, Egypt, and North Africa, regions that had been major centres of Christian theology, monasticism, and sacred art.

To the Byzantines and Latins alike, it was a spiritual as well as political earthquake. They had always conceived of Christendom as the rightful heir to the world of the Caesars. The sea belonged to Christian sailors, the cities to Christian bishops and scholars, the deserts to Christian monks. Now, monasteries were silent. Pilgrimages ceased. Christian art in Egypt, Syria, and Mesopotamia entered a long twilight.

Christianity in 600 - heresies and divisions

Before Islam complicated things, Christianity was already facing deep internal divisions, particularly over the nature of Christ. The empire-wide faith that had once seemed united under Constantine and his successors was increasingly fractured along linguistic, theological, and political lines. The Council of Chalcedon in 451 had defined Christ as having two natures - fully divine and fully human - but not everyone accepted this formula. In Egypt, Syria, Armenia, and beyond, large Christian populations rejected Chalcedon and followed their own bishops, developing distinct liturgical and theological traditions.

These weren’t just abstract debates, they had real consequences.

Read about the glories of 4th - 6th century Egyptian monastic art here:

The mystical art of the desert; the iconography of Egyptian solitude

The Desert Transfigured: Coptic Monastic Art

Greek-speaking Chalcedonians dominated the cities of the eastern Mediterranean, especially in administrative and ecclesiastical roles. However, large populations of Copts in Egypt, Christians in Syria and Mesopotamia, and Armenians followed their own bishops and traditions. Many of these groups rejected the Council of Chalcedon’s definition of Christ’s two natures, holding instead to miaphysite or other theological positions in the Christological controversies. These divisions weaken local political and social loyalty to imperial rule, a vulnerability no one yet recognises.

In Rome, the popes maintain spiritual authority but wield little temporal power. Italy is fragmented between Byzantine provinces and Lombard dukes. The Western Empire is a dim memory. The rule of the Merovingian kings in Gaul is a mess of intrigue and is perpetually destabilised by violent rivalries.

Across the Channel, Anglo-Saxon kingdoms - perpetually at war - are slowly converting to Christianity. The missionaries sent from Rome are working alongside monks from Ireland, whose vibrant, ascetic faith and artistic genius are shaping the sacred culture of the far northwest.

In the deserts of Egypt, monastic life continues to flourish. The great cenobitic monasteries still ring with the chanting of psalms, and Coptic artisans paint frescoes of saints with almond eyes and stylised gestures. To the south, in Christian Ethiopia, churches are hewn from rock, and the Gospel is sung in Geʽez. The faith that once spread along Roman roads now travels by caravan, river, and oral tradition.

The Christian world is vast but is now no longer a well-ordered, interconnected unit. There is no single power holding it together, neither Rome nor Constantinople. Communication is slow, travel is dangerous and theology is often contentious. Yet despite the fractures and regional variations, there remains a shared sense of belonging to the one Body of Christ. Liturgies vary, but the Creed is chanted. Languages differ, but the icons speak wordlessly across divisions.

What no one yet sees is that this fragile and far-flung Christian world is about to be swept by a storm. Within just a few decades, the churches of Jerusalem, Antioch, and Alexandria will be under Islamic rule. Pilgrimage routes will be severed. The ancient Christian cultures of Syria and Egypt will be cut off from the imperial centre and from each other.

What Sacred Art Looked Like in This World

As the old world teetered and the new one rose, sacred art reflected the spiritual, political, and theological landscapes of its time. It did not merely survive this era of upheaval; it spoke it, shaped it, and in some cases, defied it. What follows is a brief survey of the major regional styles just before the world began to change.

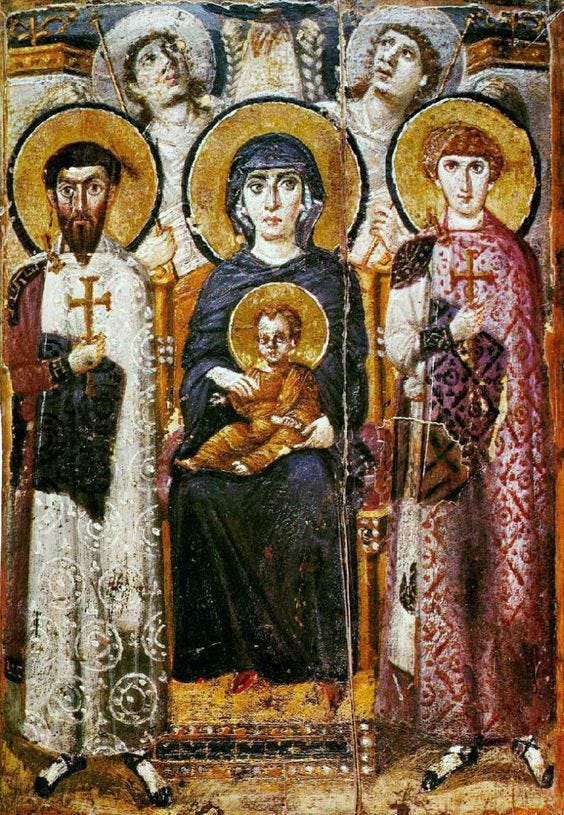

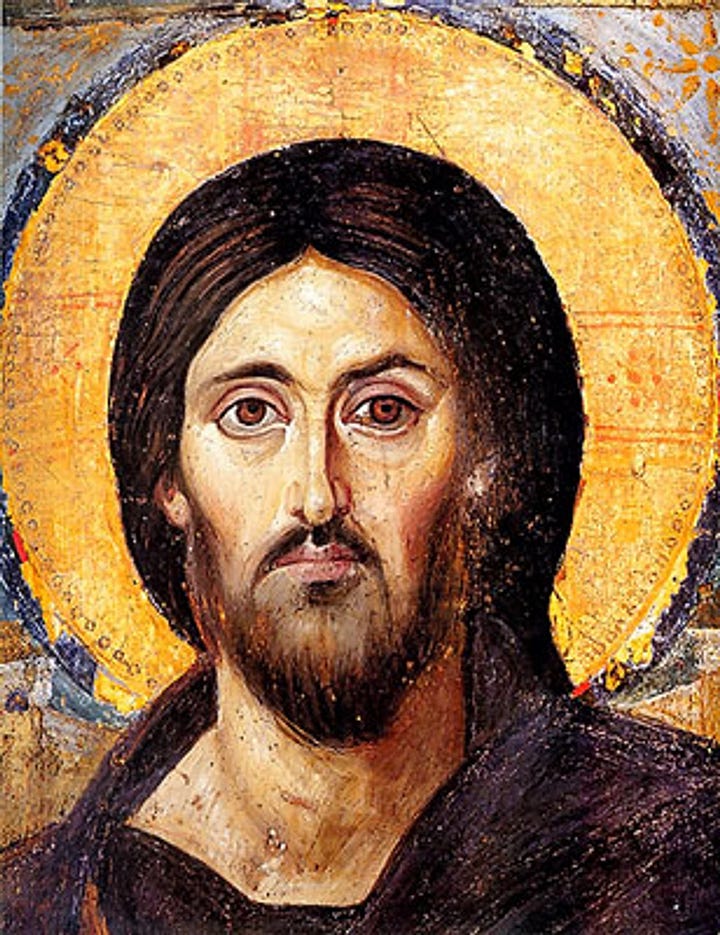

Byzantium: Icons Before the Storm

In the Byzantine East, the icon tradition had already become spiritually and liturgically central. These were not simply devotional images; they were theological statements in visual form, integrated into the liturgical and civic life, shaped by centuries of reflection on the Incarnation is one of the oldest surviving examples of this theology in paint. Stern yet merciful, frontal and commanding, the figure sets a prototype that would echo through Orthodox iconography for centuries.

Mosaics in churches such as those in Thessaloniki, including the Church of Saint Demetrios, reflect the serenity and balance of early Byzantine sacred art. Saints stand tall, golden backgrounds shimmer with unearthly light, and the human form is stylised yet dignified. This was a world where sacred images were integral to worship, where theology was expressed in pigment and tesserae. But this luminous tradition stood at the edge of a crisis: the theological and political turmoil that would erupt with Iconoclasm was just over the horizon.

Rome: East Meets West in the Churches

In Rome, sacred art remained vibrant, especially in the decoration of churches under papal patronage. Mosaics continued as a dominant medium into the seventh century, with popes like Honorius I commissioning extensive cycles. These mosaics combined Eastern compositional clarity with Latin theological emphases: Christ as Lawgiver, Mary as Theotokos and queen, saints as intercessors.

The frescoes of Santa Maria Antiqua, layered and eclectic, offer a unique glimpse into this transitional moment. The chapel served as a visual crossroads. Eastern icons, Western narrative cycles, and even hints of provincial and popular styles coexist on its walls. This is where the Italo-Byzantine aesthetic begins to take shape, neither purely Roman nor purely Eastern, but a synthesis that would define sacred art in Italy for centuries to come.

The British Isles: The Dawn of Insular Art

In the far West, Christianity had only recently taken root, but sacred art was already flourishing, thanks in large part to the monastic foundations, though it took a radically different form.

The Book of Durrow, produced in the late seventh century, is an early monument of Insular illumination. Abstract, geometric, and symbolic, its pages are filled with animal interlace, knotwork, and sacred geometry.

In the art of Celtic Christianity, the gospels were treated not only as texts but as sacred objects, and their decoration served to consecrate the Word through beauty.

Coptic Egypt and the Syriac East: Art in a Changing World

In the aftermath of the Islamic conquests, Christian communities in Egypt, Syria, and Mesopotamia retained a measure of autonomy, especially in religious and artistic matters. The Copts, already distinct in language and theology, continued their artistic traditions under Muslim rule. Coptic wall paintings and icons feature flat, stylised figures with wide eyes and formal gestures. This was art that prioritised spiritual clarity over classical form.

In the Syriac-speaking East, sacred art persisted in manuscripts. Biblical scenes, portraits of evangelists, and decorative frontispieces carried on earlier traditions even as political and social conditions changed. These communities, increasingly cut off from the Byzantine world, nonetheless remained devoted to their visual languages. This was an art of continuity, endurance, and memory in exile.

A new phase coming

By the middle of the 7th century, much of the Christian world had been permanently transformed. The Byzantine Empire retained control of Constantinople and parts of Anatolia and the Balkans, but its dominance over the eastern Mediterranean was gone. Egypt, Syria, Palestine, and North Africa were now under Islamic Arabic rule, a culture vastly foreign to the native Christian, Zoroastrian and Jewish populations, instantly reducing them to religious minorities within a new political and legal framework.

Despite these changes, sacred art did not disappear. In the East, iconography continued to develop, although it would soon face a shattering internal challenge during the period of Byzantine Iconoclasm. In the West, artistic traditions now largely cut off from their Byzantine and Mediterranean roots, adapted to shifting political structures, from the fragmented kingdoms of Italy and Gaul to the rising influence of monastic centres in Britain and Ireland.

In regions under Muslim rule, Christian communities, now “dhimmis” in their own lands, preserved their visual traditions within new constraints, often focusing on manuscript art, textiles, and local church decoration.

In the next post, we’ll be looking more closely at each of these new situations, how specific Christian communities responded artistically and theologically to life in the new political reality.

But WHY did Islam spread so quickly? What was its draw? I guess the question remains today. There is so much about it that is cruel and nonsensical. And the treatment of women so terrible.