Where Christian Art Begins; 3rd to 6th centuries

A fresh 2025 start for The Sacred Images Project

Back to the beginning and looking ahead

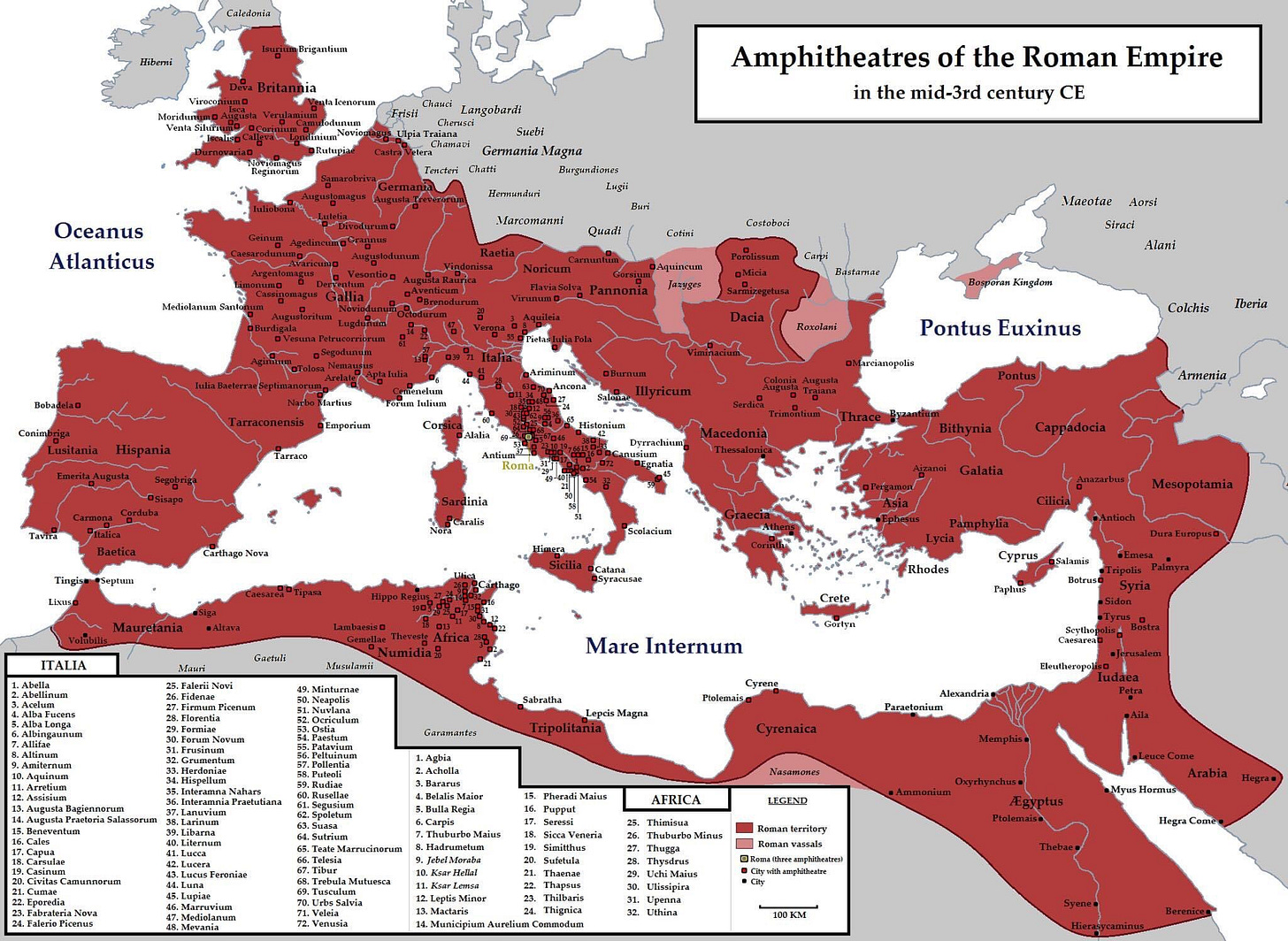

The year is AD 250. Across the sprawling Roman Empire, gilded statues of Jupiter and Mars glint in the midday sun, their watchful gazes presiding over cities, from Deva (Chester, UK) to Berenice, Egypt, that pulse with commerce, politics, and pagan rituals. At the empire’s heart, Rome has been transformed by the early emperors into a magnificent city of marble and supreme power. Yet beneath this grand façade lies a world of fear and uncertainty.

The empire is reeling. Plagues have swept through the population, famine threatens the provinces, and barbarian incursions press against the frontiers. Emperors rise and fall with dizzying speed, each claiming the favour of the gods to legitimize their rule. Amid this turmoil, a small but growing movement gathers in quiet corners: Christians, worshipping a crucified Jewish carpenter and itinerant preacher from Judea - who openly and bizarrely claimed, to the fury of his own religious leadership - to be the one and only God, through whom and for whom all things were made.

For these believers - increasingly from higher classes - faith is both a source of hope and a dangerous liability. Violent and bloody persecutions flare under rulers like Decius and Valerian, whose edicts demand public sacrifices to the Roman gods, a test of loyalty to the Romans’ deified state. Refusal marks Christians as traitors, exposing them to imprisonment, confiscation of property, torture and gruesome execution.

But for many, persecution is a test, and their resolve does not waver - it is the age of martyred saints. In secret, they celebrate the Sacraments, pray, preach, teach, share meals, and console one another, their gatherings lit not by the torches of Roman streets but by the dim, flickering light of hidden lamps.

Why We’re Back at the Beginning - Sacred Images Project Reboot

You may have noticed that we’ve suddenly shifted from the golden splendour of the Ottonian dynasty - the founding of the Holy Roman Empire and the monastic reform of Cluny Abbey in the 10th and 11th centuries - all the way back to the opening act of the show.

In today’s post for all subscribers, we’re back to the 3rd century, when the Christian faith was still a quiet rumble beneath the surface of the Roman world. Why? Because this is the opening of 2025, and this year, we’re pressing the reset button and starting the story over from the very beginning. We’ve covered a few posts on this period, but I think there are a lot of readers who missed all that. Today we’ll give a general overview of what we’re going to be covering in more detail this quarter.

We’re doing this to bring focus and clarity to The Sacred Images Project as a whole. Since I started all this, with about 1600 subscribers, we’ve kind of bounced around a lot. And that’s been great; I’ve had a blast just talking about whatever random amazing sparkly things have come to my attention. But in the last year, we’ve developed a lot too, including having just today, tipped over 5000 subscribers with a total following of over 6200.

With such a huge crowd, I thought something of a reboot was really warranted. I had no idea when I started that this subject would be of such broad appeal, so I treated it more like a hobby.

A reboot lets us bring fresh focus and structure and direction to what we’re building together. By starting at the beginning and working chronologically, we can explore the story of Christian art as it unfolds, laying a foundation that connects All The Dots between the early Church, the medieval world, and at least starts to explain how we got here.

Stay tuned for a separate “admin” post into everyone’s inbox giving the plans in greater detail. There’s still lots more in the works to talk about - thrilling stuff!

At the Sacred Images Project we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. The publication is supported by subscriptions, so apart from plugging my shop, there is no advertising or pop-ups. It’s my full time job, but it’s still not bringing a full time income, so I can’t yet provide all the things I want to and am planning for.

You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week.

For $9/month you also get the second half of the third post, plus a weekly paywalled in-depth article on our great sacred patrimony. There are also occasional extras like downloadable exclusive high resolution printable images, ebooks, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts.

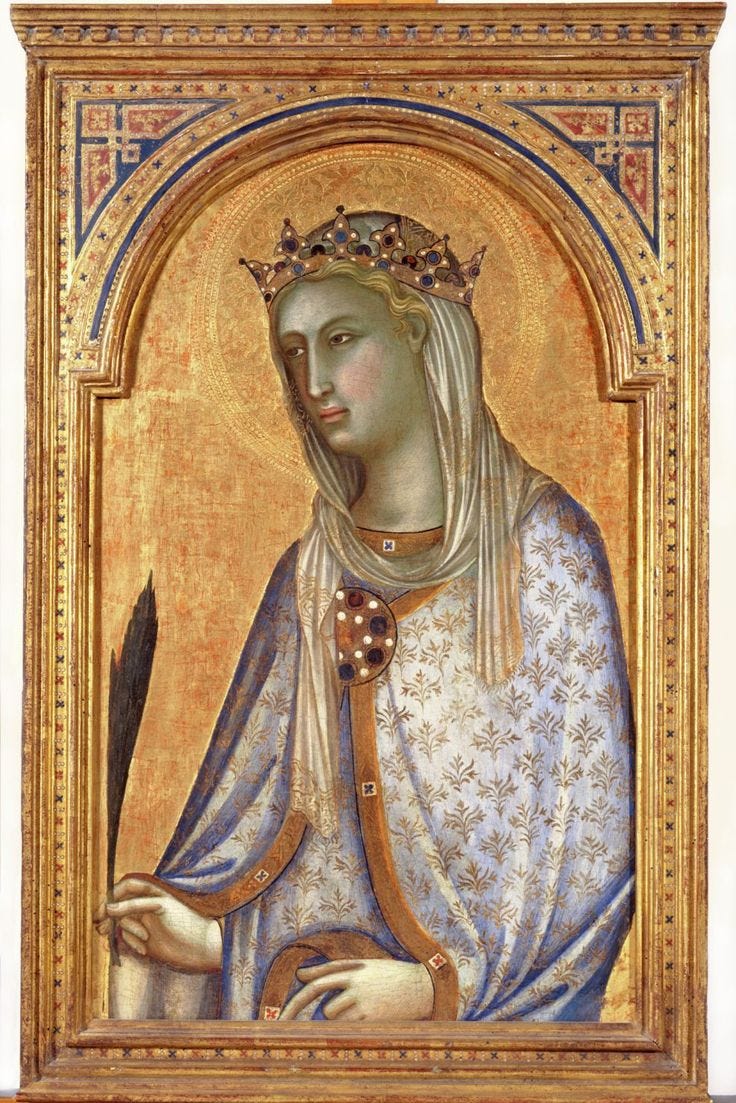

At the Met, I found this gorgeous painting by Bartolo di Fredi, a successor (after the Black Death) to the great Sienese masters Duccio di Buoninsegna and Simone Martini, and have created a standing masonite panel print from it.

I think it would make an elegant addition to a prayer corner or mantel.

You can order one here:

A quick overview: 1st Quarter, 2025 - the catacombs to the start of the Byzantine

This quarter, From January to the start of April, we’ll be covering the 3rd to 6th centuries, starting at the very roots of Christian sacred art in the Roman Empire. In the earliest days of persecutions, Christianity was a secret, quiet revolution simmering beneath the surface of the great super-state. Persecution periodically forced believers into hiding, but it also forged a unique artistic language of symbols and subtle messages, that could be hidden in plain sight, most of which is still known today.

We’ll descend into the catacombs, where early Christians buried their dead, gathered for worship, and left behind some of their most enduring artistic expressions. We’ll look at house churches, the private homes transformed into spaces for sacred gatherings, from the centre in Rome to the furthest edges of the empire.

And we’ll step outside the Italian and Greek heartlands of the empire to explore the diversity of Christian art in the provinces and its connections to the monastic movement. From Egypt to Palestine, we’ll see how local cultures shaped the artistic expressions of this growing faith. Finally, we’ll touch on the dramatic transformation that followed Constantine’s legalization of Christianity, setting the stage for the public and monumental art of the post-persecution era.

Through this journey, we’ll trace how the art of the early Church grew out of persecution, secrecy, and resilience, evolving into a tradition that would shape entire civilizations.

Symbols of a hidden faith

Our long journey to the glories of the Ottonian, Romanesque and Gothic begins in a time of shadows and furtive symbols, of quiet resistance and profound faith. It is here, in the margins of the empire, that the seeds of Christian art take root and will one day transform the very culture that sought to suppress it.

In this terrible, purifying fire of suffering and faith, the earliest expressions of Christian art begin to emerge. Unable to build grand temples or openly display their beliefs, these communities weave symbols of their hope into the fabric of their clandestine lives. We’re familiar still with some of them: the simple fish drawn in the dust, an anchor etched into a stone wall, or a shepherd carved on a tomb.

The anchor represented hope and steadfastness: Epistle to the Hebrews: “We have this hope as an anchor for the soul, firm and secure” (Hebrews 6:19). To the persecuted, the anchor symbolized both spiritual stability and the promise of salvation amidst the storms of life. Each image spoke volumes to those who understood this secret visual language.

There were others.

The peacock, less familiar today as a Christian symbol but still popular throughout the middle ages, carried a striking message of immortality from folk beliefs that the peacock’s flesh did not decay. St. Augustine wrote in The City of God:

For who but God the Creator of all things has given to the flesh of the peacock its antiseptic property? This property, when I first heard of it, seemed to me incredible; but it happened at Carthage that a bird of this kind was cooked and served up to me, and, taking a suitable slice of flesh from its breast, I ordered it to be kept, and when it had been kept as many days as make any other flesh stinking, it was produced and set before me, and emitted no offensive smell. And after it had been laid by for thirty days and more, it was still in the same state; and a year after, the same still, except that it was a little more shrivelled, and drier. - Book XXI, ch. 4

Another enduring image was the palm branch, drawn from both Jewish and Roman traditions. It symbolized victory and triumph, particularly over death, and was closely associated with martyrdom. Carvings of palms were often found on the graves of those who had given their lives for the faith, proclaiming their ultimate victory in Christ.

Since this time, the usual symbol in all Christian iconography for a martyr has been the palm branch.

Even the grapevine, a symbol borrowed from the Greco-Roman world, held profound Christian significance. Representing the Eucharist, it spoke of unity, spiritual nourishment, and the abiding presence of Christ. Its intertwining vines and clusters of grapes reminded believers of the words of Jesus: “I am the vine; you are the branches” (John 15:5).

These simple images were later to be combined in infinite variations as the more familiar, public forms and canons began to develop, and continued to be used for centuries.

The life of solitary prayer: Beginnings of the Monastic Movement

At this time and into the later 3rd century, as the Roman Empire grappled with political instability, and Christian persecution reached new heights, a quiet yet transformative movement began to take root on the fringes of society. Christian monasticism was born from a desire to live out the Gospel in radical simplicity and devotion, the early monastics sought the solitude of deserts and remote regions to escape the distractions and moral compromises of the world.

We’ll explore how the early monastic movement in Egypt influenced Christian art during its formative centuries. As the desert monastics established settled, orderly communities, their ascetic way of life fostered a distinct artistic sensibility, and monastic art started to develop that would further the purpose of union with God. Early monastic art took the form of encaustic paintings, wall frescoes, and mosaics, reflecting a blend of Greco-Roman/Byzantine and Egyptian/Syrian styles and techniques with Christian themes.

Constantinople and the Byzantine

By the late 4th to 6th centuries, after Constantine moved the imperial capital to Byzantium, Christian art had fully emerged from its early clandestine roots and entered a phase of monumental and triumphant expression. The legalization of Christianity, slowly leading to its establishment as the dominant religion of the Roman Empire, gave rise to grand basilicas adorned with intricate mosaics and elaborate frescoes.

This period marked the beginnings of a distinctly Byzantine style as we know it still today, as the eastern half of the Roman Empire solidified its cultural and political identity. In the cultural and political centres of Ravenna and Constantinople, Christian art began to embrace rich symbolism and shimmering gold mosaics that would define Byzantine aesthetics for centuries.

Fresco and mosaic were become a key medium, alongside the written and spoken word, for teaching theology, reinforcing both ecclesiastical and imperial authority, and celebrating the glory of God. Images of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and the saints began to take on more formalized, canonically iconographic styles.

Meanwhile, in the West, the collapse of Roman authority led to regional adaptations influenced by “barbarian” European cultures from which the Carolingian would emerge. These hybrid styles, blending Roman, Christian, and local artistic traditions, laid the groundwork for the vibrant art of the early medieval period. The 6th century thus serves as a bridge, connecting the classical traditions of the Roman world with the spiritual and stylistic innovations of the early medieval Christian era.

A new structure growing under the imperium

In one sense, the persecuting emperors were correct: the Christians were quietly building an alternative state, complete with its own administrative structure, but also quietly creating an entirely new culture. Beneath the veneer of Roman power, this growing network of believers organized itself with bishops, deacons, and presbyters who mirrored civic and imperial hierarchies in their roles.

Their gatherings, though hidden in homes or catacombs, fostered a sense of unity and purpose that transcended local communities. Like every other human culture, they expressed themselves visually, and their art, symbols, style and meaning, has carried down to our own time.

This state within a state posed a subtle yet profound challenge to the Roman order. It offered not just a new way of worshipping but a radically different vision of loyalty, belonging, and ultimate authority, one that centred on Christ rather than Caesar. Through their art, rituals, and shared symbols, early Christians were crafting a culture, a civilisation, that would outlast the empire itself.

Remarkable read. I have enjoyed spending my free moments with this post today, and I’m glad to be on board at the rebirth of the project. Looking forward to the journey.

Enjoyed reading about the earliest Christian art making in depth. Thank you for the returning to the beginning. It will help me understand how iconography took shape in later centuries.