Part II, The desert and the pursuit of holiness

We hear terms like "sanctification" and "holiness" a lot, but are we ever told what they actually mean? How do you get there from here?

Site update: the annual summer slow-down

I’m going to apologise ahead of time for the low level of output we’re going to have here for the next few weeks. We’re entering the hottest period of our year right now - as I’m sure so is everyone in the northern hemisphere. For me, the Big Hot is the time of year where I can’t really function. Since chemo wrecked my endocrine system 13 years ago, I’ve had considerable difficulty with the summer heat.

This is the weather that gives me the strange waves of nausea, racing heart and dizziness, a hormonal reaction I’m told, that makes it impossible to work. Nothing to be done about it but rest. I’ve got some herbal remedies that help, but it’s simply not going to be possible to keep up with the full writing schedule.

So, I missed our Wednesday paid post yesterday, and today we’re going to have a repost of a set of articles I wrote some time ago for One Peter Five on mysticism, asceticism, and the spiritual life in the ancient Christian tradition. I’m afraid this week has been a bit of a dud for writing. Or being able to concentrate on much of anything.

We have a portable AC unit, which runs in the workroom, but even with it chugging away at full blast, it isn’t much of a match for the great ravening yellow monster in the sky, especially with our three big south-west exposure windows. The view down the valley is always wonderful, but this time of year I’d gladly trade it for a cave in the mountains.

The house is so hot this time of year that we keep the front sitting room closed entirely, with the blinds down and the connecting doors shut, as well as the kitchen door, in hopes of keeping the beast at bay. But even so, all the denizens of the house are camping in the workroom at night with the AC running, and to heck with electric bills. Any cooking that gets done is in the electric slow-cooker, which sits out on the terrace with the long extension cord to keep it from heating the kitchen up any further and taxing the fridge and freezer chest compressors.

For some reason, I managed to choose nearly the hottest place in the country to live in. In Siena last week we met a young chap from Egypt working the counter in a gelato shop who said it is so hot in central Italy he would prefer to go home to Alexandria. I don’t blame him; it’s only 83F there today.

Narni is in every other way, and for the whole rest of the year, perfectly congenial. But for about 3 weeks every summer, I am obliged to simply hide indoors, and resign myself to being more or less non-functional except for about three hours early in the morning.

I’ll do my best to keep up with our regular schedule, and there’s loads of things on the calendar, and we’ll get to them one at a time. I’ve got a post half finished on the great Carolingian “Renaissance” - that time the pope crowned an emperor, and changed western European history forever. Tomorrow we’ll take a look at our quiz answers from two Friday Goodie-bag posts ago, and a little sneak peek for paid members of our glorious trip to Siena.

Benedictine book club

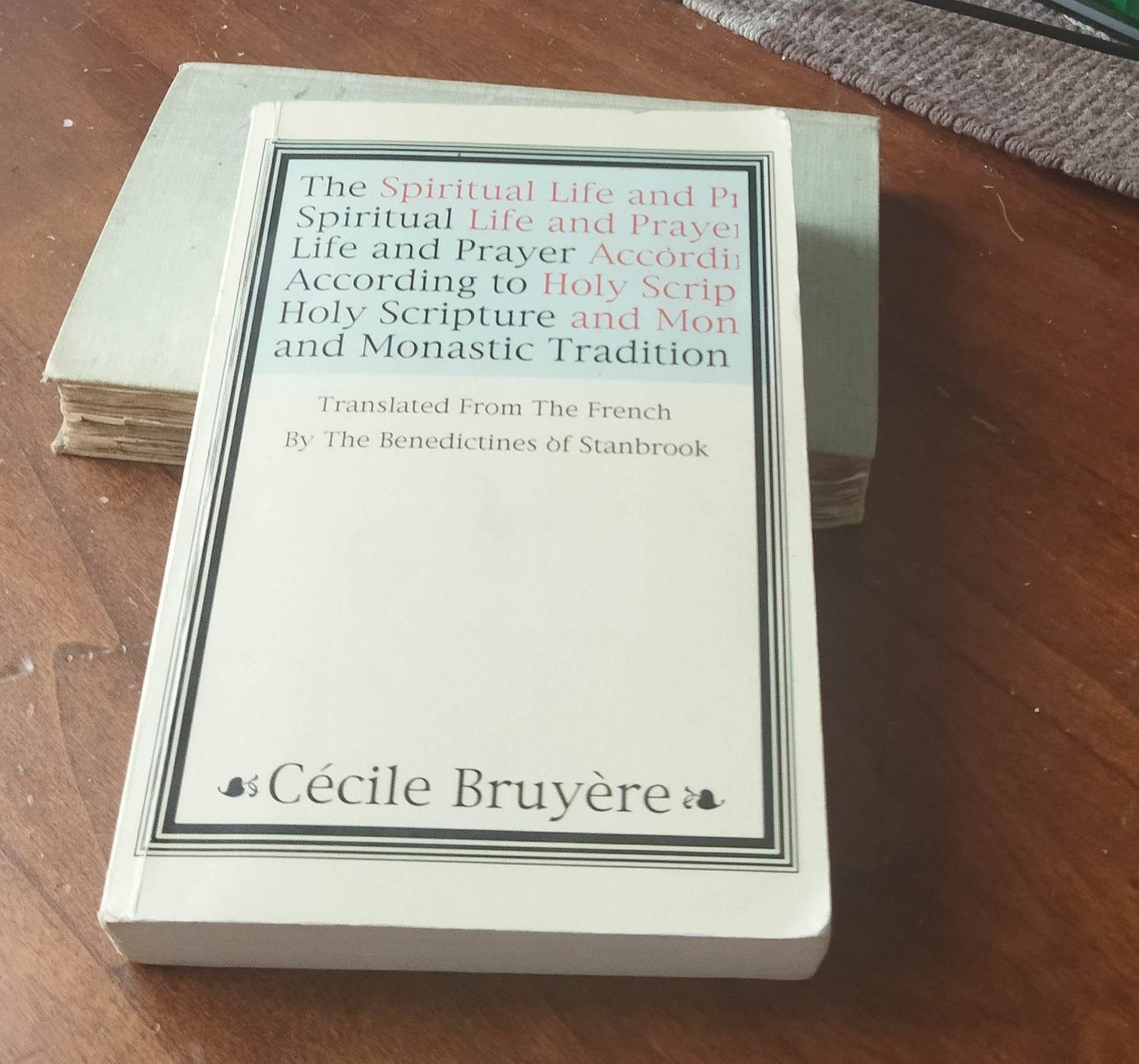

But I’m getting excited about our exploration of Benedictine monastic spirituality and prayer I mentioned in the paid section of Monday’s post. Quite a few of our members messaged that they’re interested in joining the book group. We’re going to be starting with the book, “The Spiritual Life and Prayer According to Holy Scripture and Monastic Tradition.” Quite a few said they already own it, (which speaks volumes about the quality of our members here, I have to say). If you’re interested and don’t have it yet, you can order a copy here and here.

I was able to spend about 1/2 an hour with her this morning, and even in the preface there are deeper insights than one usually gets from the average Sunday homily.

We’ll be starting the book group on Monday, and I hope it will just be a fun group talking about what we learn and think about from the readings. I suppose as the instigator I should set the assignment; I’m just reading the Preface at the moment, so that seems like enough to be getting on with.

Meanwhile, I thought if we were going to be starting a serious exploration of classical Christian mystical theology - which is what all the Benedictine stuff is - we might like to review some background…

The Sacred Images Project looks at art history and Christian culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of Christian sacred art.

A big thank you to all who have signed up as free subscribers, and hello to our new paid members. Your contributions not only make it financially possible for me to continue this work, but are a tremendous encouragement to me that other people out there take these subjects as seriously as I do.

This is my full time work, and I rely upon subscriptions and patronages from readers like yourself to pay bills and keep body and soul together.

You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week. For $9/month you also get a weekly in-depth article on this great sacred patrimony, plus extras like downloadable ebooks, high res images, photos, videos and podcasts (in the works).

I hope you will consider taking out a paid subscription to help me continue and develop this work.

(For those in straightened financial situations, fixed incomes and vowed religious etc., I’m happy to help. Drop me an email explaining and I can add you to the complimentary subscribers’ list.)

The other way you can help support the work is by signing up for a patronage through my studio site, where you can choose for yourself the amount you contribute. Anyone contributing $9/month or more there will (obviously) receive a complimentary paid membership here.

You can also take a scroll around my online shop where you can purchase prints of my drawings and paintings and other items.

I hope you’ll join us by subscribing: