Into the Desert Solitudes of the Fathers

Who were the Desert Fathers, and how can we follow them now?

An ordinary man became the “Father of All Monks”

In the heart of the great bustling metropolis - and centre of learning and culture - that was 3rd century Alexandria, the capital of the Roman province of Egypt, a young man lived who loved Christ, and wanted to know Him. Anthony1 was neither wealthy nor particularly well-educated, but he was perceptive, spiritually sensitive, and, above all, searching. He lived simply, carrying out his daily routines with little fuss. One day, while attending a local gathering of Christians, he heard a passage of Scripture that struck him like lightning: “If you want to be perfect, go, sell what you have and give to the poor, and you will have treasure in heaven.”

These words seemed to dismantle his attachment to the ordinary and worldly, pulling him toward a different, deeper existence. Not long afterward, Anthony sold his inheritance, gave away everything he owned, and left his comfortable life behind. With little more than the clothes on his back, he made his way out of the noise and distractions of the city and there, in the vast silence and privation of the Egyptian wilderness, he spent the rest of his life seeking God, often in complete solitude2.

St. Anthony’s journey from ordinary, devout Christian life in a normal urban setting, into the actual, literal desert was a deeply personal, voluntary response to a profound inner calling. In his time, the official, canonical ecclesiastical structures that we now call “religious life” did not exist. Unlike later monasticism, which became highly institutionalised, Anthony’s path was his alone, driven by a simple yet radical desire to seek God above all things.

He was not a priest, a scholar, or a man of influence, but an ordinary person who felt the divine invitation to a life of dedication and spiritual growth - the interior life. His story is not about the “founding of monasticism” but about a single person’s sincere search for union with God.

In today’s post for all subscribers, we’re taking a journey back to the Egyptian desert, where the story of monasticism, in the person of St. Anthony the Great begins. His story and the story of the movement he represents is an invitation to seek something beyond ourselves, even in the midst of our postmodern madness.

We’ll explore a history - the Desert Fathers - that is unfortunately not widely known among Latin Catholics, though it is preserved as a living tradition in the East. The story of the Desert Fathers is a remarkable tradition of wisdom, asceticism, and spiritual insight that is not well known among Latin Christians, but continues to thrive in the Eastern Church.

A quick note for print customers - how to get a nice finish on your wood panel prints

I made this little video for our friend Jeff - a great patron of the arts - who bought one of the Virgin of the Embroidered Foliage wood panel prints.

I got one of these prints for myself and am quite pleased with the quality and accuracy of the colours, but I found the plain finish of the wood wasn’t as nice as it could have been. So I’ve been suggesting to customers that a good way to improve its appearance is to give it a few coats of natural shellac varnish. This is the same substance commonly used to finish egg tempera and later early Gothic paintings in the period. It’s very inexpensive, easy to get and not difficult to apply.

Here’s the result when I did mine today. It’s now got three coats and the difference in depth of colour is magical. Three is about as many as you should do at one time, and I’ll let it sit overnight now to cure. The first couple of coats sink into the wood, so if you are looking for a nice shiny finish, at least three or four are best.

Always leave plenty of time between coats - at least half an hour for the first three, then overnight before doing more. Use long, even brush strokes and try not to go over the same spot too much. Don’t worry about the brush marks; we’ll sand them off when the shellac is fully cured. Then I’d suggest a final glaze with a commercial spray varnish, something like Windsor and Newton’s acrylic satin finish, since it’s got good coverage and UV protection.

You can order a print and lots of other nice things at the shop:

At the Sacred Images Project we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. The publication is supported by subscriptions, so apart from plugging my shop, there is no advertising or annoying pop-ups. It’s my full time job, but it’s still not bringing a full time income, so I can’t yet provide all the things I want to and am planning for.

You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week.

For $9/month you also get the second half of the weekly Friday Goodie Bag post, plus a weekly paywalled in-depth article on our great sacred patrimony. There are also occasional extras like downloadable exclusive high resolution printable images, ebooks, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts.

If you would prefer to set up a recurring donation in an amount of your choice, or make a one-off contribution, you can do that at my studio blog.

This helps me a lot because the patronages through the studio blog are not subject to the 10% Substack fee.

I’ve been restocking the online shop with some of the printed items for this year’s Sacred Images Project Christmas market. Like this little Sienese Gothic angel tree ornament:

People tell me all the time - and I’ve found this myself - how difficult it can be to find really nice religious cards and decorations for Christmas. So I’m focusing this year on cards and tree ornaments that will bring some medieval imagery into your holidays.

Enjoy a browse:

Who are the Desert Fathers?

Our main source of information about the life of St. Anthony the Great is the “Life of Anthony” (Vita Antonii), written by St. Athanasius, the bishop of Alexandria3, around AD 360. This biography is one of the earliest Christian hagiographies and was written shortly after Anthony’s death. Anthony’s example inspired a movement of men and women seeking God in solitude and contemplation that lasts into our own time, and laid the foundations of all Christian spiritual practice - the pursuit of “Theosis” or the “Transforming Union.”

We’ve talked a bit about the purpose of monastic asceticism, and touched briefly on the progression from Anthony to St. Benedict.

Part IV of the desert and the pursuit of holiness

I came to cast fire on the earth, and would that it were already kindled!

After Anthony’s fame as a holy example spread throughout the Roman Christian world, other Christians were inspired to renounce ordinary life and join him in the desert. Soon, caves, remote huts, and makeshift shelters dotted the barren landscapes of remote desert areas in Egypt, and abroad in Syria.

And so, from then on, there were monasteries in the mountains, and the desert was made a city by monks, who left their own people and registered themselves for the citizenship in the heavens.

St. Athanasius, Life of St. Anthony

What had been a barren, uninhabited landscape gradually filled with small communities and solitary ascetics, turning the desert into a thriving center of monastic life. This saying emphasizes how the spiritual commitment of the Desert Fathers and Mothers reshaped the wilderness into a new kind of “city” dedicated to prayer, discipline, and the pursuit of holiness.

Although these early hermits did not yet live under a single formal rule, a culture of mutual support emerged among them. They shared wisdom, aided each other in times of need and passed down “sayings” that would be recorded and eventually form a rich treasury, a core of monastic insight.

When the holy Abba Anthony lived in the desert he was beset by accidie and attacked by many sinful thoughts. He said to God, ‘Lord, I want to be saved but these thoughts do not leave me alone; what shall I do in my affliction? How can I be saved?’ A short while afterwards, when he got up to go out, Anthony saw a man like himself sitting at his work, getting up from his work to pray, then sitting down and plaiting a rope, then getting up again to pray. It was an angel of the Lord sent to correct and reassure him. He heard the angel saying to him, ‘Do this and you will be saved.’ At these words, Anthony was filled with joy and courage. He did this, and he was saved.

Sayings of the Desert Fathers

By the time of Anthony’s death, the “desert way” had established the foundations of Christian monasticism. These early pioneers offered a path of radical devotion that would influence generations of monastics across the Christian world, from Syria to Gaul, and leave an indelible mark on Christian spirituality.

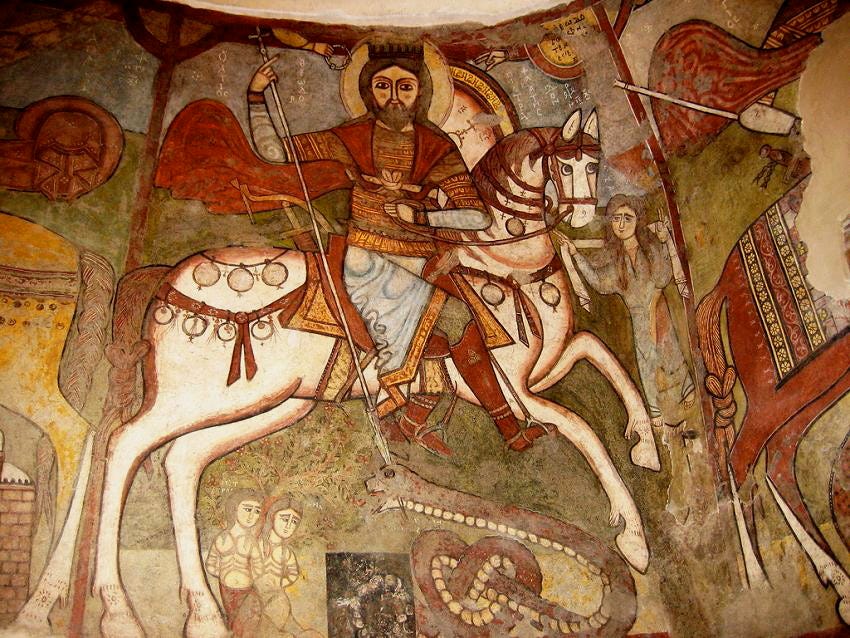

The Combat of the Desert

The desert was as much a place of testing as it was of spiritual growth, and people of that time knew it as a place where demons dwelt. In this stark and unforgiving environment, with every possible distraction removed, the monk discovers the intensity of temptation. He is assailed by visions and dreams that seemed to lure him back to the world, whispering of the pointlessness of the whole thing, and offering promises of wealth and security - a “normal” life.

Abba Anthony said to Abba Poemen, ‘This is the great work of a man: always to take the blame for his own sins before God and to expect temptation to his last breath.’

He also said, ‘Whoever has not experienced temptation cannot enter into the Kingdom of Heaven.’ He even added, ‘Without temptations no-one can be saved.’

Sayings of the Desert Fathers

For Anthony, whose temptations are detailed in Athanasius’ book, the visions transformed over time, becoming dark, ominous phantoms, as if something powerful was determined to pull him back to the world he had left behind.

But Anthony persisted, and eventually his reputation reached every Christian community in the region. People heard that in the far reaches of the desert lived a man who was facing down both the demons of this world and the inner struggles of the soul, and they came to him in crowds.

A hunter in the desert saw Abba Anthony enjoying himself with the brethren and he was shocked. Wanting to show him that it was necessary sometimes to meet the needs of the brethren, the old man said to him, ‘Put an arrow in your bow and shoot it.’ So he did. The old man then said, ‘Shoot another,’ and he did so. Then the old man said, ‘Shoot yet again and the hunter replied ‘If I bend my bow so much I will break it.’ Then the old man said to him, ‘It is the same with the work of God. If we stretch the brethren beyond measure they will soon break. Sometimes it is necessary to come down to meet their needs.’ When he heard these words the hunter was pierced by compunction and, greatly edified by the old man, he went away. As for the brethren, they went home strengthened.

Sayings of the Desert Fathers

The story of Anthony’s courage inspired others. Each came alone, one by one, and lived alone in his or her own solitude, yet bound together - the communities came to be called “lauras” - by a common desire to purify the heart and enter into God’s presence as much as was possible in this life.

By the time of Anthony’s death, he had become a legend, the “Father of All Monks.” His life had sparked a revolution in Christian spirituality, drawing others to abandon cities and comforts for lives of radical devotion. This movement of Desert Fathers and Mothers would spread far beyond Egypt, inspiring generations to come with their simple, profound wisdom and their powerful example of lives fully dedicated to God4.

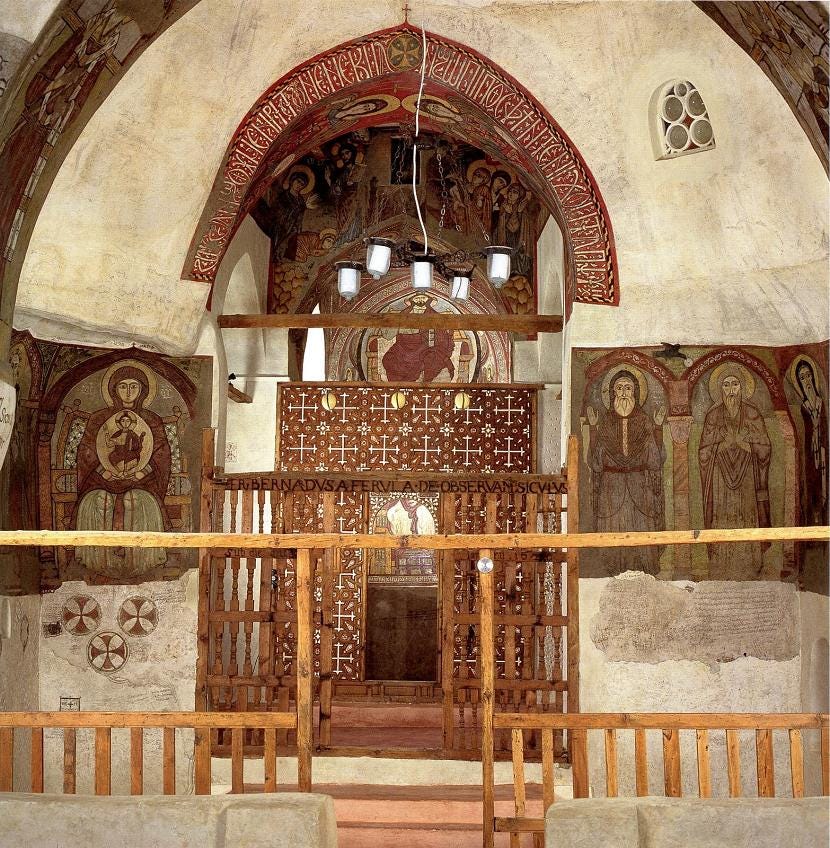

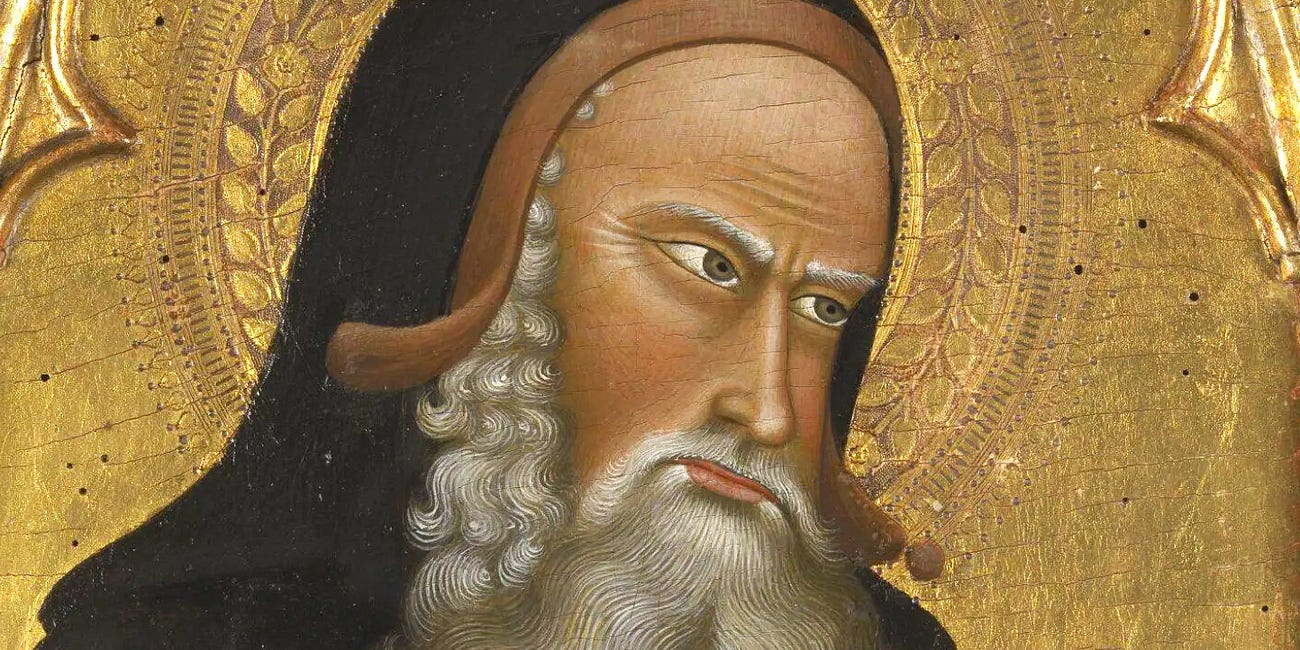

Coptic iconography; the art of fierce Egyptian desert asceticism

An eye and mind trained to love the sensuality of Gothic and Renaissance art, with its deep jewel-like colours and intricate naturalism, would be inclined to dismiss Coptic art as “primitive.” But to understand Coptic monastic art, we need to embrace its intentional starkness and intensity. Coptic art does not aim to please the senses, create visual illusions or capture the beauty of the world as it is. Instead, it is driven by a powerful spiritual purpose: to confront the viewer with the realities of the sacred, the unseen, and the eternal.

This is the art of desert asceticism visual. It strips away the decorative, drawing the viewer into a contemplative space. To stand before a Coptic icon is to hear at least a faint whisper of an invitation into the combat of the desert.

The figures in Coptic icons, rendered in bold, geometric austerity reflect the strength and single-minded dedication of the Desert Fathers. Their large round eyes, completely open and staring directly, unapologetically forward, capture your gaze, and arrest your mental fidgeting. Their solemn expressions allow no merely aesthetic or human admiration

These images are not concerned with naturalistic corporal beauty but with conveying a commanding, otherworldly presence from which we dare not flinch. The faces are stylized and unadorned, stripped of individualistic features that might connect them to the everyday. In their gaze and their gestures, there is a sense of timelessness and intense stillness, a visual embodiment of the monks’ unyielding focus on God and their separation from worldly distractions.

In Coptic frescos and icons, colours are often limited to earth tones of natural pigments: reds, yellow ochres, charcoal black, creating a visual language as stark and elemental as the desert they come out of. The art reflects the rejection by the desert monks of material excess and mirrors their ascetic ideals; every detail is carefully chosen, not to embellish, but to point beyond itself.

In this art, we don’t see the glamour of human achievement; we see an invitation to spiritual endurance, a call to forget the passing world, and look inward and upward, to the realms of God and eternity.

Coptic art doesn’t idealise or embellish but rather communicates a spiritual urgency, inviting us to see beyond the surface and sense the deep conviction and ferocious dedication of these extraordinary early ascetics.

c. 251 - 356

Though St. Anthony is famously known as the “Father of All Monks,” he was not entirely alone in pioneering the monastic life. He sought the guidance of an older ascetic, known to history as St. Paul of Thebes, who is sometimes called the “first hermit. This of course is disputed. The story of St. Paul of Thebes primarily comes to us from St. Jerome’s later account, The Life of St. Paul the First Hermit. Jerome wrote this biography in the 4th century, well after Paul’s life, and his work drew heavily on oral traditions and local legends. The ascetic, eremitical life was certainly already known in the places where Christianity took root, and has been practiced in some way by all cultures.

From 328 until his death in 373, though his tenure was interrupted multiple times by exile due to his staunch defence of Nicene Christianity against Arianism.

You can buy a copy of the Sayings of the Desert Fathers at Amazon.

Grateful always for your thorough well-written treatments!

Well, just when I thought this is something *only* would know, I see this on Substack. Thank you for highlighting the Desert Fathers. But have you also heard of the "Desert Mothers" as well?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Desert_Mothers