Wait… Did we forget the fall of Rome?

Errr… yes. Well. About that…

It’s what comes of trying to cover absolutely everything in this incredibly complex history, and in the theory and philosophy of sacred art, across the entire Christian world… Yeah…

Ok, I probably should have talked about the fall of the Western Empire. We were just merrily tripping along to Torcello and Asturias and back and forth to Constantinople and having a lovely time with Lombards and Visigoths and Egyptian monks, Italo-Byzantine and early Romanesque…

So here we are, late but circling back to the bit where the Western Roman Empire quietly collapses and the world doesn’t end. But it does change, including in its western iteration of Christian art. Power has shifted and the western Church becomes something new: no longer just a privileged religion within an empire - with the pope under the emperor - but the custodian of unaltered truth, memory, culture and beauty in a world becoming increasingly fractured politically and culturally.

Since this story is so well known and easy to research, I thought we’d just go through the ABCs of the Fall of Rome quickly, pointing out and correcting some of the many misapprehensions we might have picked up from Hollywood.

To start with… Rome wasn’t actually the capital, and hadn’t been for a while…

I honestly didn’t notice that we’d just skipped it until I was sitting down with the freelance book editor I’ve engaged to produce our first ebook and she said, “Wait… we’re in the 8th century already? What happened in Rome? Where did the Ostrogoths go?” Ah. Yes. Looks like we might have skipped a bit.

The good news is that I’ve engaged a freelance book editor (a good friend who’s read us from the start) and the first book is finally coming. It was just too much to get done for me alone with everything else. And the reason I’ve been able to engage help is the number of people who’ve subscribed in the last year and a half that we’ve been doing this. It’s really changed everything.

In today’s post for all subscribers, we’ll rewind and look at the end of the Western Empire, after centuries of weakening, and the start of the Ostrogothic Kingdom of Italy, and what happened next.

At The Sacred Images Project, we explore Christian life, thought, history, and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. This work is entirely reader-supported. No ads, no algorithms, just careful research and thoughtful analysis, made possible by your subscriptions.

Free subscribers receive a weekly article uncovering the treasures of Christian tradition. Paid subscribers ($9/month) receive a second weekly piece, plus bonus posts with high-resolution images, video explorations and more.

If you value this work and want to help it grow, I hope you’ll subscribe to join us below the fold today:

From the Shop

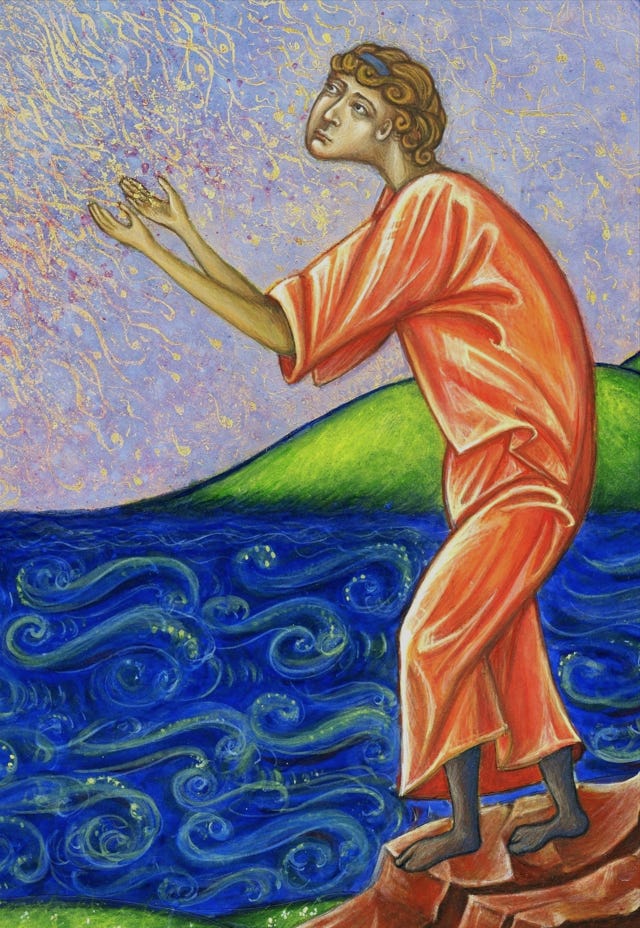

I’m happy to offer prints of this little figure, part of a painting - egg tempera and gold leaf - I did for a client in the contemporary Byzantine iconographic style. He is the speaker in Psalm 84, Quam Dilecta: “My soul longeth, yea, even fainteth for the courts of the Lord: my heart and my flesh crieth out for the living God.”

If you’d prefer to set up a monthly contribution in an amount of your choice, you can also do that at the studio blog, or make a one-off donation to help keep this work going. If you subscribe through my personal page, I’ll add you as a complimentary subscriber here. And thank you.

The nutshell version of what happened: Rome fell - but it was kind of time

I may have forgotten to cover it because in reality it was a bit of a non-event. Thomas Cole’s fanciful academic painting here shows a cataclysmic, all-consuming disaster: temples burning, mobs rioting, statues toppling, ships sinking, bodies strewn across a collapsing cityscape, which is more or less how we’ve been taught to think of it. But this is not what happened in Rome in 476. The last western emperor, Romulus Augustulus, was quietly deposed and sent off to retirement. There was no sack in 476, no flames, no tidal wave of chaotic destruction. Unfortunately for romantic painters, the historical reality was gradual, bureaucratic and anticlimactic.

In 476 AD, the boy-emperor Romulus Augustulus1 was deposed, after reigning only about ten months, by the barbarian general Odoacer, and that’s the conventional date for the “fall” of the Western Roman Empire. But what actually fell was the last remaining shred of imperial authority in the West. In the east, emperors carried on in Constantinople for another thousand years. In the West, daily life didn’t suddenly stop, though it certainly changed. The Church remained standing and bishops and clerics stepped into civic leadership roles as senatorial power faded. Many Roman churches from this period are still in use, and had already provided shelter to the city’s population during the sack of 410 by Alaric.

What really collapsed was centralised administration and senatorial power. It hardly needs saying that Odoacer didn’t overthrow the Roman Empire at its peak of peace, power, and prosperity. By 476, the Western Empire was already a shadow of its former self; militarily overstretched, economically broken, politically fragmented and increasingly reliant on barbarian generals to do the actual ruling.

Yes, there were sackings

The old city of Rome, of course, was sacked multiple times before 476, each time chipping away at the idea of Roman invincibility, even though the Western Empire as a civil entity technically survived them.

410 AD – Sack of Rome by the Visigoths

Visigoths under Alaric I

Rome was part of the crumbling Western Roman Empire.

The city was besieged multiple times; sacked in August 410.

Lasted three days, with looting but relatively little destruction.

First sack in over 800 years, a massive psychological blow to the Roman world2.

455 AD – Sack of Rome by the Vandals

Vandals under Genseric

Sacked at the invitation (or under the pressure) of Empress Licinia Eudoxia.

Lasted two weeks; more thorough looting than in 410.

Vandals took treasure, artworks, and captives, including the Empress and her daughters.

Pope Leo I reportedly negotiated to spare the city from wholesale burning.

472 AD – Sack of Rome by Ricimer’s Troops

Invaders: Troops loyal to the Germanic general Ricimer during a civil war.

Ricimer besieged and sacked the city in a struggle for control of the puppet emperors.

Less famous than 410 and 455, but still violent and destabilising.

Rome suffered starvation and unrest during the siege.

As far as overthrowing empires, that wasn’t really ever the job of sackings. And that would have been pointless anyway, since from the late 3rd century onwards, due to military and logistical pressures, the capital of the Western Roman Empire had moved. In the late 3rd–early 4th c., Milan (Mediolanum) had become the administrative capital under Diocletian and then Constantine. Then, around 402 AD, under the emperor Honorius3, and pressure from the Visigoths, the capital was moved again to Ravenna, which was easier to defend being marshy, coastal and well-positioned for communication with the East.

After the Visigoths sacked Rome in 410, a psychologically catastrophic event, the Western Empire steadily lost control of Britain4, much of Gaul, and parts of Spain and North Africa. Even after 476, Ravenna remained the seat of the Ostrogothic Kingdom under Theoderic and then of the Byzantine Exarchate, meaning it still had strong Eastern Roman/Byzantine political and artistic influence.

All of which explains why all the sackings of Rome itself were merely demoralising, rather than empire-ending.

But the pope stayed in Rome

All the shiftings of imperial civil power notwithstanding, the city of old Rome remained the spiritual and symbolic centre of Western Christendom, and of course the “Holy See” of the pope. It was the city of Saints Peter and Paul, and the site of their martyrdom. The bishop of Rome held a unique prestige among the patriarchs of the Christian world due to Rome’s apostolic foundation, even if his political power was limited. Over time, as the Western Roman state collapsed and the emperors faded from relevance, the popes began to take on more civic, diplomatic and cultural authority, always speaking from the old city.

A good pope and a steady hand: Pope Simplicius

During the reign of Odoacer (476–493 AD), the bishop of Rome was Pope (St.) Simplicius5, followed by Pope Felix III. Simplicius was already pope when Romulus Augustulus was deposed, and was a witness of the formal end of the Western Roman Empire. Simplicius took it in stride, accepting Odoacer’s rule (despite his Arianism) while also maintaining a strong relationship with the Byzantine emperor Zeno. He worked to protect the Church’s rights in Rome amid growing political instability, and was involved in defending orthodoxy against Christological heresies after the Council of Chalcedon.

Simplicius opposed Monophysitism, especially its extreme form, Eutychianism, which denied the full humanity of Christ by teaching that Christ had only one nature after the Incarnation. He supported efforts by Eastern Emperor Zeno and Chalcedonian bishops to uphold orthodoxy.

Rome itself had been Christianised through a long process since Constantine promulgated the Edict of Milan. Pagan temples began to lose state support, with some being repurposed, or simply neglected and closed. Experienced church visitors in Italy always know to look closely at the capitals of the columns in older churches. If they don’t match, or are different heights, they likely came from disused Roman pagan temples that were used as quarries of ready-made, finished building materials.

Laws were enacted against public pagan worship and sacrifice, the Altar of Victory6 - the symbol of the empire’s dedication to the civic pagan religion - was removed from the Senate House by Constantius II in 357. Pagan aristocrats slowly lost influence and many prominent Roman families converted during this period. In 380, the Emperor Theodosius I, issued the Edict of Thessalonica, making Christianity the official state religion of the Roman Empire.

As the western imperial power - and government’s bureaucratic apparatus - moved out of the city, the clergy, with their large administrative networks and charitable institutions, gradually filled the vacuum. The bishop of Rome, once just one among five apostolic patriarchs within the imperial system, began to take on civic as well as spiritual authority. Clergy were tasked with overseeing grain distribution, cared for the poor, managed endowments and estates, and even mediated with invading forces.

In a city no longer ruled by emperors, it was often the pope who acted as Rome’s de facto ruler.

What next? The Ostrogothic Kingdom - not that bad, actually

With the imperial system gone, there was no more tax-funded infrastructure, no more big imperial building projects like bridges, roads and aqueducts, and no more wealthy urban elite commissioning large-scale art in the name of the Roman imperium. Cities shrank, trade routes faltered and what remained of public life turned inward. The grand visual language of empire; the triumphal arch, the equestrian statue, the illusionistic mosaic, gave way to smaller, more symbolic and more portable forms of art.

The shift away from central power and money meant that regional styles began to emerge. Ecclesiastical and monastic patrons replaced imperial commissions, and the Church became the great cultural conservator, of the faith and of historical memory, literacy and artistic tradition. Sacred art in the West would never be quite the same again, but it never stopped growing and developing.

In Italy, the Ostrogothic Kingdom under Theoderic (493–526) preserved a degree of stability and even patronage, especially in Ravenna, which remained the capital. Theoderic, though an Arian Christian, maintained Roman institutions, employed Roman and Byzantine artisans and allowed the Catholic Church to function freely. His court sponsored significant architectural and artistic works in a classical-imperial style, blending Gothic authority with Roman forms, most famously seen in the mosaics of Ravenna’s Sant’Apollinare Nuovo.

Meanwhile, in Rome itself, papal patrons continued commissioning mosaics in basilicas like Santa Maria Maggiore and Santa Pudenziana, maintaining a visual continuity with late antique traditions even as political power shifted elsewhere.

This was not a rebirth of empire, but it was a kind of post-imperial continuity, in which sacred art still spoke the visual language of Rome, even as the world around it changed.

I was struck by the words: “And the pope stayed in Rome.”. Despite sackings and looting and chaos and imperial decline… The pope stayed in Rome. Thanks to the Sacred Arts Project for all that you do.

(Please forgive the typo: It's obviously The Sacred Images Project!!!)