AI images: Whatever it is, it's not "sacred art"

The "Robert Powell Problem" in iconography explained

Today someone I follow with interest on Twitter posted this image:

With the caption:

“2 Kings 19:22 Who is it you mocked and ridiculed? Against whom have you raised your voice and lifted your eyes in pride? Against the Holy One of Israel! Save us, Saviour of the world. Heal us, free us, break our chains.”

Someone on her feed said she liked it and asked who the artist is, and Julianne said she didn’t know, “I just steal stuff off of the Internet.” Fair enough. Don’t we all. The thing is, she must not have looked very closely at it, because close inspection would show there is no artist. In fact, it’s not a work of “art” at all.

I’ve been seeing this all over social media, especially in the art groups on Facebook. Almost every day someone will post an image purporting to be a Monet, for example, and there will be a long string of gushing praise for it in the comments: “Gorgeous!” “What a talent!”

Uh, yeah. Except, no.

AI programmes can make images, but not art

I don’t know why - maybe it’s to do with the 4 years of observational training I had in drawing classes - but I seem to be able to spot artificially AI-generated images without even trying. They get used a lot on social media as illustrations for posts, so they’re getting peppered all over our feeds these days. And I can always spot them, even if at first glance they look superficially convincing. I didn’t even have to pause long enough to count the fingers on the right hand in this one; it just has all the earmarks in its style, lighting, colour and general look, of an AI image.

This button will take you to my studio blog, Hilary White; Sacred Art, where you can see a gallery showing my progress learning how to paint in the traditional Byzantine and Italian Gothic styles. It includes a link to my PayPal where you can make a donation or set up a monthly support to become a patron. Many thanks to those who have already contributed. At the moment, patronages, one-off donations and occasional sales of paintings are my sole source of income. If you’ve enjoyed this site, I hope you’ll consider donating so I can keep doing it.

I wrote to Julianne saying, “There is no artist. It's an AI generated image. (Count the fingers.)”

A few moment’s inspection shows that this is not only not a work of sacred art; it’s not a work of art, strictly speaking, at all. To be art, it has to be made by a human mind and imagination and - at least remotely - by a human hand. AI isn’t that.

And these programmes famously struggle with facial symmetry, hands and other fine points of human anatomy. Apart from the general air of weird unreality about it, the rule is to count the fingers, and see if the eyes and nose match.

And these are the kinds of details professional training in observational drawing taught me to spot at a glance. (Not that six fingers is that hard, really.) From the point of view of the normal standards of religious painting, even abstract and “contemporary,” no one trying to produce a genuine sacred image would put a cross or crucifix where the Sacred Heart is supposed to be. This image doesn’t “speak the language” of Christian sacred art, even its late 19th and 20th century corrupted forms. In other words, it’s not a theological image.

What most people don’t realise is that these AI images aren’t the result of human work of any kind. These programmes allow the creation of images by writing a line of text into a space like a search window. You type a “prompt” like, “Jesus, dramatic low lighting, monochrome, dark heart background,” and click the button. A minute or so later, you’re given a choice of four automatically generated images to choose from. You pick one, click, “develop” and it generates more details on the chosen image. The programme “learns” what images are by scouring the internet. The algorithm creates an image that is an amalgam of thousands or millions of images posted online.

At no time is the user given an opportunity to do any editing or adding to the image himself. This isn’t photoshop where you’re altering an existing image, nor is it like any of the programmes that simulate painting to make “digital art”. AI images are entirely automatically created by the programme. Your input is only the typed commands.

Anyway, Julianne’s post made me think again about what sacred art is and isn’t, and how we got here. What follows is an edited version of the Twitter thread I wrote about it.

Who are we praying to?

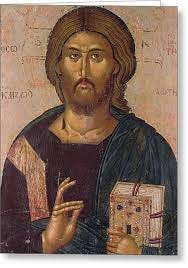

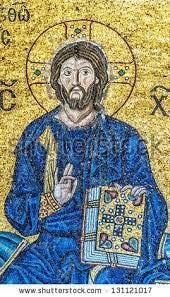

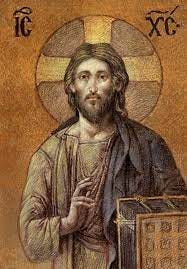

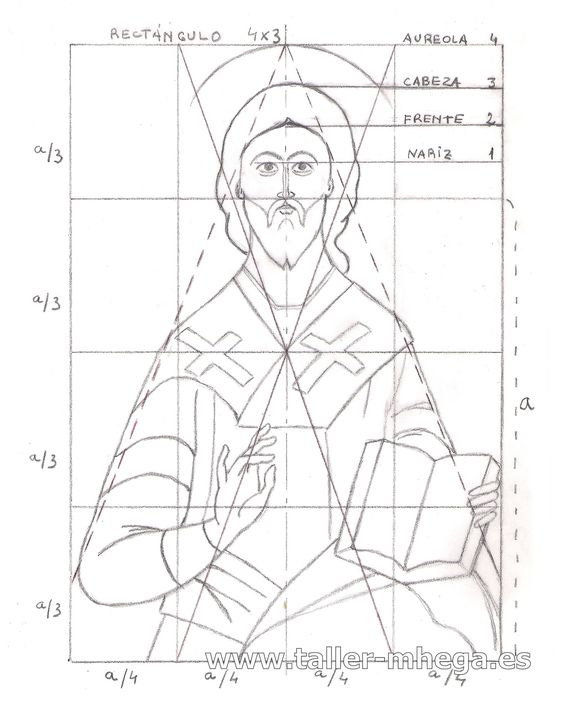

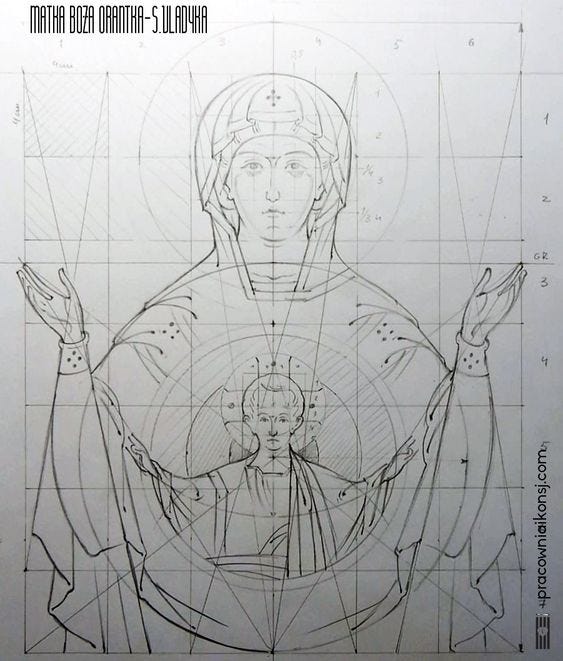

In the great tradition of Christian sacred art, icons intended for prayer, especially liturgical prayer, are created using a set of "canons", a kind of standardised mathematical map of the human face and figure.

This is why they look more or less the same. It's done like that intentionally so there's never any confusion about who or what is being depicted, and most importantly prayed to. The canonical icon cannot be mistaken for some random guy, like a movie actor or a model.

It is extremely important in Christian worship to be absolutely clear about who, precisely, is being depicted in an icon or painting intended for prayer and veneration: Christ; not an actor known for playing Him in a film; the Theotokos, not a model hired for a sitting.

Once we understand this it becomes more clear why, for example, Caravaggio’s depiction of the Death of the Virgin was rejected as unfit by the parish for whose altar it was intended. It was believed that the painter had used a well known Rome prostitute, his own mistress, as the model for the Virgin Mary.

The illusionistic realism so masterfully displayed by this painter1 - famous in his own time - would mean that a portrait of a prostitute, “cast” to “play” the Blessed Virgin and most pure mother of God, in the painting, would be offered for veneration by the ordinary faithful. It’s easy to see why such a thing would be rejected as a sickening prospect, almost a sick joke.

Robert Powell would like you to stop praying to him.

Take a look at the face again: recognise it?

You probably think it's a fairly standard image of the face of Christ. But it's actually a specific person who is still alive. The actor Robert Powell played Jesus in a movie, Jesus of Nazareth, in the 1970s. So definitively did he capture the role, and so successful was the film, that ever since, Robert Powell's face has become a kind of cultural western iconographic image of the face of Christ. If you looked at that automatically generated AI image and assumed without thinking that it was Jesus, then you've unconsciously assumed the face of that actor as a mental "icon" of Christ.

This is a publicity still from the film that has sunk into the collective public awareness and been labelled "Jesus". Now, I've nothing at all against the idea of actors playing Christ in movies. I think this Zeffirelli film was terrific, and recommend it, as well as the Mel Gibson Passion.

So captivating was his depiction of Christ that it is natural that people come away with the mostly-unconscious idea that they've seen the real Christ. Which was certainly the point of making the film in the first place. You're supposed to go to the movies and think you're there in the action. You're supposed to feel as though you've had an adventure with Captain America, or gone with Frodo and Sam to Mount Doom, or fought with Aragorn on Pelennor. That's the point.

But it's a psychological illusion, and you're expected to understand the difference between the onscreen images and reality. You're supposed to "suspend disbelief," willingly and to know the difference between the fantasy of the film and real life in the theatre lobby.

The problem comes in when you take a movie still like that, and use it to create works of art intended to depict Christ Himself, not the actor who played Him. And painters do this because in western Christendom, the concept of the iconographic canon was lost and forgotten about 1500. So if they want to depict Christ they have to turn to other “standard” images everyone will recognise.

This painter has fallen into that problem. It's a good painting (in the modern illusionistic style) based, as he has said, on the image of Powell from the Zeffirelli film. He's not trying to deceive anyone into worshipping Robert Powell. He's saying forthrightly that it's a portrait from the movie. But we end up confused anyway. Who is this? Is this painting supposed to depict Christ, or is it a painting of an actor? If you want a portrait of the actor, fine (though apart from this one role, Powell isn’t exactly an A-lister).

But if you're looking for an image of Christ Himself to venerate in your prayer life, using this image is deeply problematic, because it's not Christ. It's Robert Powell.

And brother, there's a LOT of them out there.

“Having travelled around certain parts of Europe and seen iconography, which is in churches and which is undoubtedly you, I think it's quite a remarkable thing…that you are now the perceived image of Jesus Christ…”

“…Behind the altar, the icon is you. They had found a magazine photograph blown it up and that was it you know…”

So deeply embedded in the cultural mind is this image of Powell as Jesus, that it’s not surprising the AI used him as a model. And of course, the equation of this face with Christ, with its very particular structure, comes out of the iconographic tradition. Zeffirelli likely cast Powell because his face was such a good “iconic” fit.

There’s a good reason we have the idea that we know what Christ looked like. This canonical depiction was standard since at least the 6th century.

People are obviously making and buying pictures of Robert-Powell-as-Jesus not out of any particular love of the actor, but because they remember being deeply moved by his performance and want that feeling again; they want an image of Jesus Christ for veneration, whether they understand what that means, in those terms, or not.

From the Renaissance Revolution to the movies: illusionistic realism vs Christian sacred art

“Creating an illusion to deceive the eye and mind isn’t what Christian worship is about.”

Ever since the Renaissance replaced canonical symbolism with realism over our altars, western Christians have been visually conditioned to think that "good art" = realism and the more “real” it looks, the better the art2. In other words, the more closely an image creates an illusion of the material world, as if you could step into the picture, the more we think it's a good picture. This in essence is exactly opposed to the purpose of Christian art, because creating an illusion to deceive the eye and mind isn’t what Christian worship is about.

Until AI came along, movies were the final expression of the Renaissance's shift from symbolic depictions to illusionistic "realism". In the Renaissance painters’ new and apparently miraculous ability to depict physical reality3, we learned the idea of the painting as an illusion of reality, perhaps more beautiful and desirable than the one we live in. Depictions of Biblical and other sacred people and events were now expected to seem like windows into the past, to allow us to “look at” these things as they appeared in history.

Modern people have taken that unconscious bias several steps forward by having their mental visual language almost entirely dictated by photography. So rarely do Modernians see paintings, and so ubiquitous have photographic images become, that we can't tell the difference any more between Photoshop, manipulated images, and reality. And this has led directly to the dominance of the Algorithm for our visual input.

But here's where it becomes a pretty big problem for religious imagery. You’re supposed to understand that the image is of the Real, a way of connecting in the here and now to the most Real thing there is. That’s what “venerating” images means in the pre-Renaissance sense.

And that is why it's not a good thing to use living models for Christian sacred art, taking that immediate and imperative confrontation with ultimate reality and mediating it through an actor, a third party who in reality has nothing to do with what the image proposes.

It’s exactly what the Second Council of Nicaea4 warned against, in fact:

“Concerning the charge of idolatry: Icons are not idols but symbols, therefore when an Orthodox venerates an icon, he is not guilty of idolatry. He is not worshipping the symbol, but merely venerating it. Such veneration is not directed toward wood, or paint or stone, but towards the person depicted. Therefore relative honor is shown to material objects, but worship is due to God alone.

St. John of Damascus

Simply, it’s bad to pray to people who aren’t saints or God. To venerate such an "icon" in the old sense of using it to communicate directly, face to face, with God, is shaving very close to idolatry.

But the Renaissance realist revolution came about because the people commissioning paintings from Leonardo, etc, were not themselves deeply spiritual men. The aim was the advance of the new Humanistic beliefs, to show off their intellectual or cultural superiority and wealth. It was no longer all about the visual preservation and promotion of Christian doctrine, Christian worship and mystical theosis.

In the end, the spiritual practice of authentic veneration of sacred images - the worship of God through the icon - died out in the western Church, and in its place was put an emotive - in other words, purely natural - admiration for the physical beauty and surprising illusion of real life presented in something like Leonardo’s Madonna of the Rocks.

All of a sudden the carefully constructed symbolic and theologically meticulous images that had been the standard visual language of all of Christendom were summarily jettisoned by this new movement of celebrity "artists”5. Faithful Christians went into their churches and no longer could be sure of who or what they were venerating. Attention was now paid to the painting as a painting, and not as a depiction of and physical connection to sacred realities.

I'm never going to argue that Leonardo's Madonna of the Rocks isn't an extraordinary and technically advanced work of art. But it's not sacred art as the term was understood across Christendom for a thousand years. We rightly put this painting in a museum, not above an altar because its value is in the natural, not the supernatural realm. It is properly valued as "priceless" because it is a Leonardo, and one of his greatest works. We have an emotional reaction of awe because of its worth as an interpretation of the beauty of natural creation.

We look at it and see an elevated, perfected and sublime material world, and wish the things and people we look at in real life looked as good as this. It elevates our natural senses to think about beauty in the natural world. All of that is to the good, for what it’s worth. And of course we marvel at the incredible technical superiority of its creator.

But none of this touches on the realm of supernatural veneration of God or sacred persons or events. None of these strictly natural goods can bridge the gulf between man and God, as true Christian sacred art is intended, and is still done in the East.

In a similar way, the Zeffirelli film was a surpassing masterpiece of the illusionistic cinematographic arts. But despite the subject, the film is not sacred art, and images made from it aren't either. This problem of illusionistic naturalism blurring the distinction between the sacred and profane art has brought us to the point where we are literally all but worshipping movie actors6.

The Renaissance frenzy for illusionistic realism and naturalistic beauty in the new "sacred art" has deeply skewed our collective cultural "mind". And this has metastasized to the point where we are losing the ability to make distinctions between fantasy and reality. And paradoxically this blurring has created the idea that the things we see aren't important. We think, Oh, what does it matter what sort of image we put above an altar, as long as we “like” it. As long as it is (naturally) beautiful. The reality, the nature of the thing itself has ceased to matter. So accustomed have we become to being, effectively, lied to by our art that we no longer think reality is important. We prefer the illusion.

Sacred images - icons - are intended for promoting the worship of God, not the idolising of the skill of a painter. Or his personality. Or his tastes. Or his ideas about God.

Thanks for reading down to the bottom, and sorry it’s been so long without a post. I suppose I was having a dry spell, and I was mainly focused on painting. A big commission is in the works.

If you would like to help me continue to do this work, you can click on my studio blog here: Hilary White; Sacred Art, where you can make a one-off donation or set up monthly support.

Many thanks to all who have contributed to make it possible to keep working - the “struggling artist” thing doesn’t last forever, but it is a struggle for a while. Stay tuned.

It is well known that Caravaggio never used the canons to create his figures and faces. He only used models, and painted them directly without preliminary drawings.

What’s forgotten of course is that actual realism has to include invisible, supernatural reality as well as the merely physical, material world seen with the eyes. The point of iconographic symbolism as a theological language is that it depicts all these aspects of reality at once.

Realism was certainly known and practiced by artists in pagan antiquity. The Fayoum mummy portraits and frescoes and mosaics of Pompei and Herculaneum showed that. It was not “lost” by an ignorant generation of Christians determined to bring about the Dark Ages. It was deliberately dropped for sacred purposes, and replaced with a different conception.

Nicaea II, AD 787, also called the Seventh Ecumenical Council, was convened to deal with the problem of iconoclasm; a movement supported by the Emperors that tried to ban the use of any sacred images in churches or homes as idolatrous. If you want to know what the undivided Church thought about icons, read about Nicaea II and St. John of Damascus (“Damascene”), the great defender of icons.

We can thank the Renaissance for the cult of “celebrity artists”. Prior to that painters were technicians hired as any other tradesmen to produce something needed for the serious work of worshipping God.

… and pop stars. cf: Paul McCartney's thoroughly creepy story of the time, at the height of Beatlemania, a mother handed him her small child. Paul ruffled the boy’s hair in friendly way and handed him back, saying he was “a lovely lad.” His mother asked, “Did you heal him?”

There is something creepy about this image of Jesus. It feels cold and manipulated. Ever since I started reading your posts about what IS sacred art and what it’s not, I have been more attentive to Byzantine icons. I live in Greece and I never paid that much attention to it, thinking that Byzantine iconography, unlike Latin Christian depictions of Christ, Our Lady and the saints, stagnated. Now I see it differently and when I go into an Orthodox Church to see icons, I find myself paying more attention to the symbolism. Icons draw you in, unlike a Caravaggio painting where you marvel more at the skill of the artist.

This was absolutely fascinating: thank you so much for sharing. I’ve always had a distaste for AI art in general, and now you’ve given me words to explain why.