Artist focus: Lorenzo Monaco - the glorious Italian Gothic

First in our series "Italian artists you've probably never heard of..."

In today’s post for our free subscribers, we will start a series looking at the various periods and schools of later Gothic sacred art by taking a close look at some of the painters who deserve to be better known. In this series we will try to put these figures into the larger context of what was going on in the rest of the art world, so to come to a more wholistic understanding as well as growing our familiarity with the various styles.

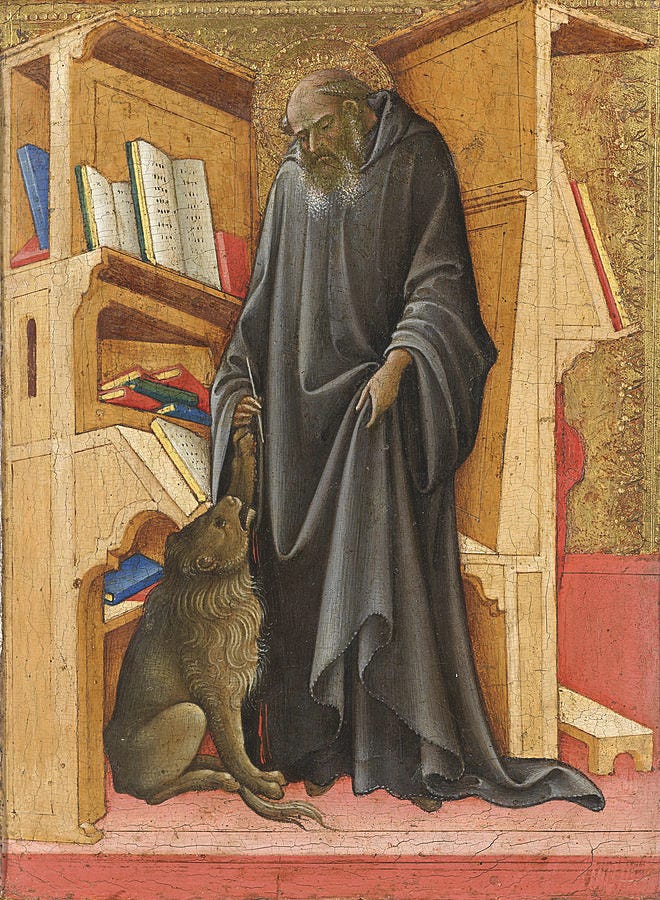

Today we’re looking at the Florentine Gothic painter, Lorenzo Monaco in the context of the movements and schools that were in a period of profound change during his time, with the later Gothic work growing north of the Alps, and early stirrings of the Florentine Renaissance in his own neighbourhood. Something remarkable is that Lorenzo Monaco’s work stands out against this background as a clear and conscious choice to turn away from Renaissance Humanism, and continue the spiritual traditions of the Gothic and Trecento1 painting.

One of the great “unknowns”

It’s terribly difficult to decide on a “favourite” of anything, isn’t it. Who’s your favourite Beatle2? What’s your favourite flavour of gelato? Painters often get asked what their favourite colour is, which is just silly. Deciding which Italian medieval painter is your favourite just seems impossible.

But if I had to answer, I’d say a contender on my personal short list would have to be Lorenzo Monaco, a monk and painter who rather defies easy categorising. Active in the late 14th and early 15th century, he followed and developed the style of the Sienese School of painters like Duccio di Buoninsegna and Simone Martini,3 while being influenced by Florentine naturalism. He was also likely influenced by the pivotal early Renaissance painter Giotto. In the end we can call Lorenzo Monaco the sub-alpine division of the International Gothic school.4

This post is free to all subscribers and readers, but I’ve prepared a little present, to make up for missing our Monday deadline. Monday’s post for paid subscribers is about the metaphysics of the Gothic, compared to the entirely different metaphysics of the Renaissance. As you might imagine that’s a complex subject so it’s taking longer than expected.

So later today, I’ll be sending out a second post only to paid members, a free downloadable PDF, a section of an upcoming ebook about the real reason the monastic life was destroyed in Europe. It didn’t happen when you think it happened (definitely not a post-Vatican II phenom) and involves some rather enthralling historical developments starting just before the French Revolution.

So, if you’re a paid member of this site you will be able to download the free PDF, which will be the text version of the first chapter of the upcoming book. The whole book will be available to purchase from my online shop soon.

Join us to begin to learn about this hidden - one might say “suppressed” - aspect of Catholic European history.

The Sacred Images Project looks at art history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of Christian sacred art.

If you would like to accompany us into a deep dive into these spiritually and culturally enriching issues, to grow in familiarity with these inestimably precious treasures, I hope you’ll consider taking out a paid membership, so I can continue doing the work and expanding it.

This is my full time work, but it is not yet generating a full time income. I rely upon subscriptions and patronages from readers like yourself to pay bills and keep body and soul together.

You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week. For $9/month you also get a weekly in-depth article on this great sacred patrimony, plus extras like downloadable high res images, photos, videos and podcasts (in the works), as well as voiceovers of the articles, so you can cut back on screen time.

We are significantly further ahead in the effort to raise the percentage of paid to free subscribers than we were a month ago, from barely 2% to just over 4.5%, but this is still well below the standard on Substack for a sustainable 5-10%.

The other way you can help support the work is by signing up for a patronage through my studio site, where you can choose for yourself the amount you contribute. Anyone contributing $9/month or more there will (obviously) receive a complimentary paid membership here.

You can also take a scroll around my online shop where you can purchase prints of my drawings and paintings and other items.

Like this painting I did last year illustrating the Psalm, “Quam dilecta” in the Greek iconographic style - egg tempera on a gilded ground.

How amiable are thy tabernacles, O Lord of hosts!

My soul longeth, yea, even fainteth for the courts of the Lord: my heart and my flesh crieth out for the living God.

And now, back to our show…

Piero di Giovanni (1370 - 1425)

Lorenzo Monaco, born Piero di Giovanni, was born around 1370 in Siena, Italy and, though he began his professional training in Florence, was strongly influenced in his work by the earlier Trecento Sienese school, particularly in terms of composition and colour. His style is now considered an example of the International Gothic style, characterized by elegant, flowing lines, delicate details, and vibrant colours.

Seeking a life of religious devotion, he entered the Camaldolese monastery of Santa Maria degli Angeli in Florence around 1390, adopting the name Lorenzo Monaco, “Lorenzo the Monk.” Though he did not remain in the monastery, his life and spiritual training there helped define his artistic journey, embedding his works with a deep sense of spirituality and devotion that would come to characterize his career.

Trained in Florence; a product of the Sienese genius

Lorenzo Monaco started his training in the workshop of Agnolo Gaddi, a prominent Florentine painter. Gaddi's influence is evident in Monaco's early works, which reflect a blend of the late Gothic style and the emerging naturalism of the period with more rounded figures and softer more realistically modelled draperies.

Rejecting Humanism and Naturalism

Despite his early association with Florence, Lorenzo Monaco’s work reflects his conscious choice to align with the spiritually oriented Gothic style that had developed in Siena, rather than embracing the Humanism and philosophical Naturalism that was fashionable in early Florentine Renaissance painting.5 He was part of a small movement that pushed back against these trends being sponsored and promoted by the unimaginably wealthy and powerful Medici family and other moneyed interests.

Many artists who, like Lorenzo Monaco, were associated with religious orders, particularly those with a contemplative and ascetic orientation such as the Camaldolese,6 remained focused on the spiritual and mystical aspects of art, emphasising divine themes and spiritual contemplation over human-centred subjects and naturalism.

While not often documented in written critiques, the commissioning preferences of monastic orders such as the Camaldolese, Franciscans, and Dominicans favoured more traditional Gothic styles and spiritual themes, implicitly opposing the naturalistic and human-centred approaches.

Notable Works

Lorenzo Monaco's oeuvre includes some of the most exquisite examples of late Gothic art. His altarpieces and panel paintings, such as the "Adoration of the Magi" (1422), are celebrated for their vibrant colours and intricate compositions. This particular piece showcases his ability to create depth and narrative richness within a single frame.

Another significant work, the "Coronation of the Virgin" (1414), demonstrates his skill in portraying divine figures with an ethereal grace and dignity, surrounded by angelic hosts in an opulent display of gold leaf and delicate detailing. These works are not merely religious depictions but are imbued with a spiritual intensity that invites contemplation and reverence.

Art for Christian spirituality

Lorenzo Monaco’s Camaldolese spirituality profoundly influenced his artistic output, (he was also a celebrated miniaturist for manuscript illumination), imbuing his work with a distinct sense of divine contemplation and monastic devotion. The Camaldolese order, a branch of the Benedictines who live in a community of small individual hermitages similar to the Carthusians, is known for their emphasis on solitude and prayer. This life shaped Lorenzo’s approach to both life and art. This spiritual framework is evident in the serene, meditative quality of his paintings, where the viewer can sense a deep, mystical devotion to the subjects depicted.

Lorenzo’s use of luminous colours and gold leaf is not merely decorative but serves to elevate the sacred nature of his work, reflecting, as it does in the Byzantine tradition, the transcendent light of the divine. This technique, coupled with his graceful, elongated figures, creates an atmosphere that is at the same time ethereal and deeply intimate, in keeping with eremitical, contemplative spirituality of the Camaldolese order.

The detailed and elaborate backgrounds in his works can be seen as symbolic of the intricate but harmonious inner life of monastic spirituality. The meticulous attention to detail mirrors the disciplined and focused nature of monastic prayer and meditation. Lorenzo’s art serves as a visual expression of the monk’s spiritual journey and yearning for heavenly perfections and glories. His paintings, therefore, are not only masterpieces of the International Gothic style but also profound meditations on faith and the divine, deeply rooted in the traditional spiritual practices of Christianity.

I hope you enjoyed this post about the great Italian Gothic painter Lorenzo Monaco.

If you are a paid member, stay tuned later today for a special post containing a gift of a PDF downloadable section of an upcoming book, “What happened to the Monasteries”.

How the Habsburg Emperor Joseph II, Voltaire, Napoleon and and 19th century European Freemasonry created a perfect storm, destroying an entire monastic Catholic civilisation.

If you’re not already a paid member, you can join us for just $9/month.

Trecento (“Tray-chent-oh”) is the Italian word for the 14th century. It’s an abbreviation of “milletrecento” or one thousand three hundred.

George, obviously.

We’re going to get to these great painters, and the Sienese school in general, in this series. We’ll get there.

You can learn more about these divisions and distinctions here: Gothic Devotion vs. Renaissance Humanism

Lorenzo and Fra Angelico lived in Florence at the same time.

Camaldolese monks are a branch of the Benedictine order, following the Rule of St. Benedict modified to allow some monks of the community to follow a more eremitical lifestyle in small single-person dwellings within the monastic enclosure. Founded around 1012 by Saint Romuald in Camaldoli, Italy, in the mountains near Arezzo. They wear a white version of the Benedictine habit.

Awesome post! Also, this is a moment of serendipity! Did you realize that today happens to be the feast of St. Romauld (founder of the Camaldolese order)? :O

I could look at those paintings All Day. 😍 The artistry is exquisite.

I think my favorite part were the multicolored angels' wings. Is there a particular reason why they painted wings in various colors instead of just in white?