Artist Focus: Pintoricchio the Gothic Storyteller of the Renaissance

Or, "Why Umbria is best"

During a time when the Florentine Renaissance was veering towards secular humanism and Naturalism in both art and philosophy, distancing itself from the deep traditions of Christian sacred symbolic imagery, one artist stood apart. Bernardino di Betto, known to us as Pintoricchio (“little painter” in Italian), carved out a unique space within this shifting cultural landscape.

Though the period’s A-listers, like Raphael and Michelangelo, pursued the natural human form and the ideals of classical antiquity, Pintoricchio remained committed to a richly decorated, narrative style that brought the earlier Gothic styles forward and preserved a sense of spiritual, symbolic storytelling.

In today’s post for all subscribers, I’m happy to present another Artist Focus on this extraordinary painter who bridged the symbolism, linearity and narrative styles descended from the Byzantine, and brought an unparalleled delicacy of touch in his human figures.

NB: To my great frustration, I’ve discovered that the photos I took of both the Perguia Altarpiece and the Baglioni Chapel in Spello have vanished somehow. I changed phones since then and I guess I didn’t save them. So, I’ll note where the photos are my originals, but I also have some pretty good books on Pintoricchio that I have scanned photos from for this piece. This is a good way of seeing some of the details that, because of their size and the difficulty of getting up close, could not really be available even if you’re in the room with them. Some of the images, therefore, will be a little grainy. Photos from other sources will be noted.

The Sacred Images Project is a reader-supported publication where we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. It’s my full time job, but it’s still not bringing a full time income. You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week.

For $9/month you also get the second half of the weekly Goodie Bag post, plus a weekly paywalled in-depth article on this great sacred patrimony, plus our Benedictine Book Club in the Substack Chat. There are also occasional extras like downloadable exclusive high resolution printable images, ebooks, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts.

If you would prefer to set up a recurring patronage in an amount of your choice, or make a one-off contribution, you can do that at my studio blog. Anyone who signs up for a patronage of $9/month or more will, of course, receive a complimentary subscription to the paid sections of The Sacred Images Project.

This helps me a lot because the patronages through the studio blog are not subject to the 10% Substack fee:

This is the site where I post photos of my own work as it develops. I have a shop there where some of my drawings and paintings are available for sale as prints, as well as some other items.

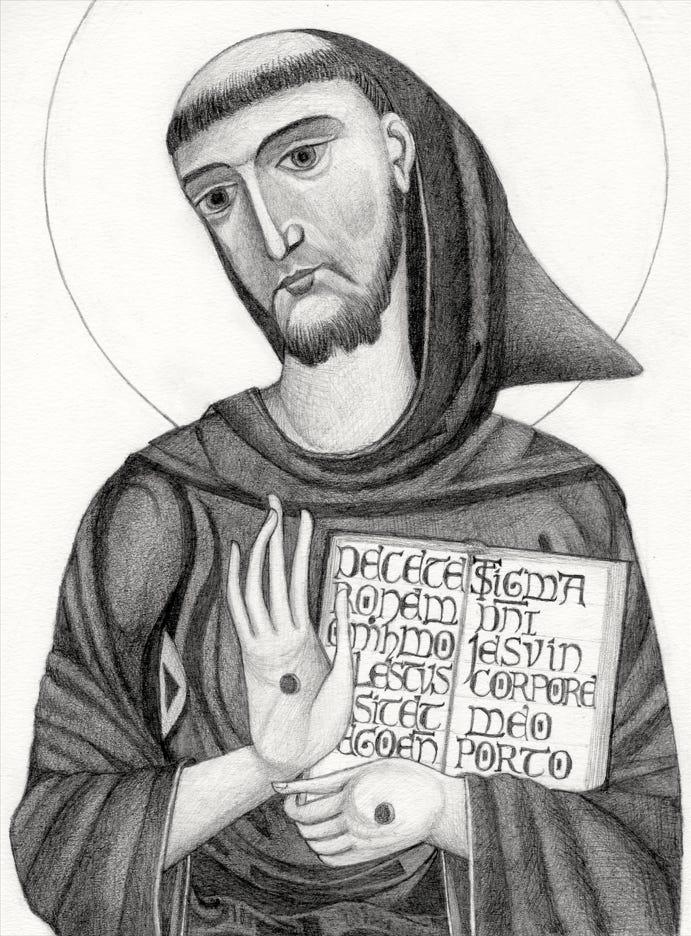

One of these that I rather like is this drawing in graphite on paper of St. Francis of Assisi in the Duecento or 13th century Umbrian style.

Pinturicchio and Leonardo were contemporaries, both active during the late 15th and early 16th centuries, yet their approaches to art couldn’t have been more different. Their careers, which overlapped during the height of the Renaissance, offer a fascinating comparison between tradition and innovation, illuminating the diverse paths that artists took during this period.

A Child of Umbria: Early Life and Training

Born around 1454 in the picturesque hills of Perugia, Pinturicchio trained within the Umbrian school, likely alongside Pietro Perugino. This region of Italy, known for its vibrant colours and harmonious compositions, deeply influenced his artistic vision. While artists in Florence, like Leonardo, embraced new perspectives and anatomical precision, Umbrian art clung to an older, more contemplative sensibility.

The influence of earlier Sienese masters, Duccio di Buoninsegna and Simone Martini, lingered in this tradition - blending jewel-like colours, refined linework, and a serene spiritual, otherworldly approach.

A Journey to Rome: Major Commissions

All these attributes were certainly known and appreciated by commissioners in his day, and Pintoricchio was renowned in Rome as well as his native Umbria. The journey from the tranquil hills of Perugia to the bustling heart of Rome marked a turning point in his career. By the 1480s, he was assisting in the decoration of the Sistine Chapel, a project steeped in political and artistic competition.

Though much of his work there was overshadowed by later additions, it positioned him for a major independent commission: the decoration of the Borgia Apartments in the Vatican. Here, amidst the rise of more humanistic themes, Pinturicchio’s love for rich decoration and spiritual storytelling shone through.

Both videos by me, July 12, 2024

In Siena, Pinturicchio took on perhaps his most enduring project: the Piccolomini Library frescoes in Siena Cathedral, commissioned by Pope Pius III.

These scenes celebrate the life of Enea Silvio Piccolomini (Pope Pius II), filled with elaborate costumes, vibrant colours, and beautifully rendered architectural details.

His work here demonstrates a balance between the Florentine fascination with classical forms and his own inclination towards the richly narrative tradition of Umbrian art.

Gothic Linearity vs. Renaissance Sfumato and Tenebrism

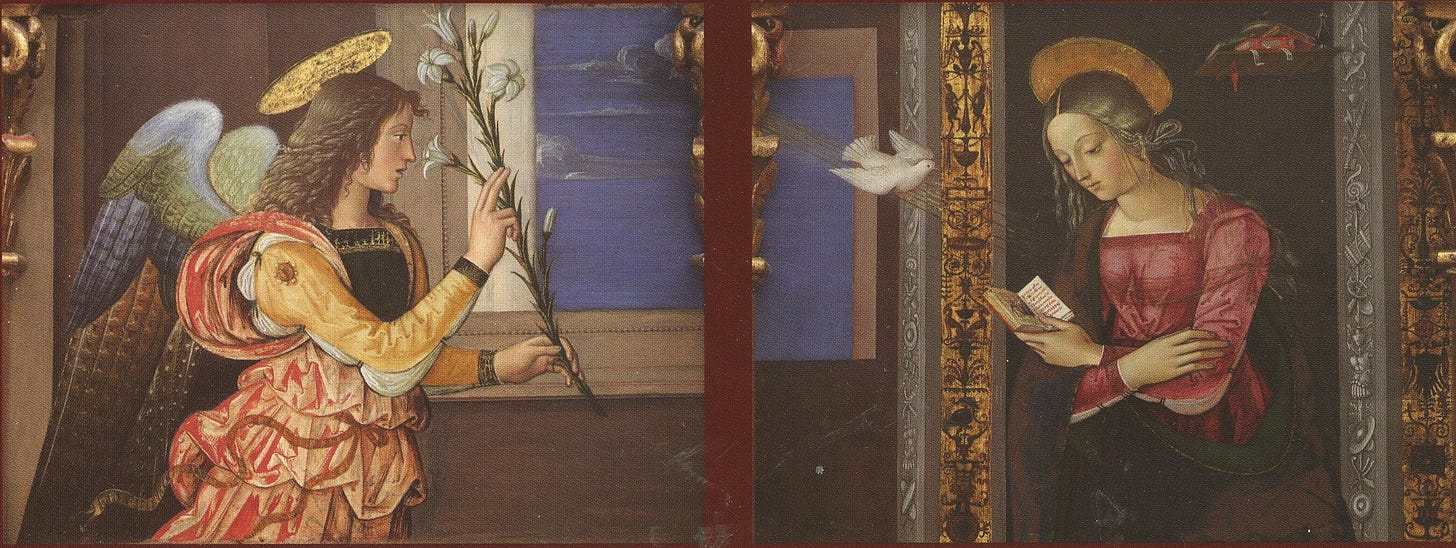

One of the key differences between Pinturicchio and Leonardo lies in their handling of light and form. Pinturicchio’s style retained the clear, defined linearity characteristic of the Gothic tradition, emphasizing structure and order in his compositions. His precisely rendered figures and architectural elements are often outlined with precision, giving them a sense of stability and rhythm that aligns with the narrative clarity of earlier sacred art.

Most importantly, the use of light in Pinturicchio’s paintings reflects an older, more symbolic understanding of illumination, which aligns with the Byzantine concept of a sacred world bathed in divine light, where shadows hold less significance. Pinturicchio’s approach to light is less about the play of light and shadow and more about creating a sense of clarity, purity, and spiritual radiance.

In Pinturicchio’s frescoes, light is often even and diffuse, filling the scene with a gentle glow that emphasizes the sacred nature of the subject matter. Rather than using shadows to create depth or to add drama, as seen in the works of later Renaissance artists

Leonardo, in contrast, developed sfumato, a technique that allowed him to create soft, blurred transitions between light and shadow, giving his figures a more atmospheric and naturalistic quality. This approach minimized the use of outlines, making the boundaries between light and dark almost imperceptible. Leonardo’s use of tenebrism - strong contrasts between light and shadow - added a dramatic intensity to his compositions, enhancing the emotional depth and mood of his scenes.

Egg Tempera vs. Oil Painting

The differences between Pinturicchio and Leonardo are further emphasized by their chosen mediums. Pinturicchio primarily used egg tempera, a traditional medium made by mixing pigments with egg yolk. Tempera dries quickly and allows for precise, smooth finishes, suiting the linear style of Gothic and early Renaissance art. Its use of thin, semi-translucent layers creates a subtle, inner luminosity, as light reflects through the layers to give a glowing effect - perfect for religious works that emphasise spiritual presence. However, tempera’s fast drying time made it difficult to blend colours as one does with oils. Colour blending in egg tempera paintings is achieved through many tiny hatch marks.

Leonardo, however, embraced the newer medium of oil paints popularised by the late Northern and Flemish Gothic painters like Jan Van Eyck. Oils dry slowly, making them ideal for what is called “direct” painting in which colours are applied and blended directly on the canvas. This technique enabled Leonardo to achieve his seamless “sfumato” transitions in tone. While oils can also be used in thin glazes for rich effects, Leonardo’s approach often focused on blending and layering directly, making his figures appear almost to emerge from the shadows, with a richness and depth difficult to achieve in tempera.

Decoration and Ornamentation

Pinturicchio’s work is especially known for his meticulous attention to decorative details. He fills his scenes with intricate patterns in fabrics, richly adorned robes, and beautifully rendered architectural elements. This focus on the ornamental recalls the Gothic tradition’s love of intricate design, yet he places these details within the more structured architectural spaces of Renaissance art. His use of detailed decoration - whether in the borders of a fresco or in the design of a saint’s garment - bridges the gap between the mystical atmosphere of Byzantine and Gothic art and the new emphasis on three-dimensional space.

Leonardo, on the other hand, focused on naturalistic detail rather than decorative embellishment. His backgrounds are often atmospheric and meticulously rendered, with a focus on realism rather than ornamentation. The rocky landscapes in works like The Virgin and St. Anne and the infant John the Baptist, pictured, serve as a natural setting, giving the impression of the viewer looking through a kind of window in time at a past event in this world.

Legacy: Two Paths Through the Renaissance

As the Renaissance’s ideals of classical perfection and secular humanism took centre stage, Pinturicchio’s reputation waned. Critics came to view his work as decorative rather than grand, preferring the anatomical precision and philosophical depth of artists like Leonardo.

Vasari’s Lives often reflects his preferences for certain ideals of the High Renaissance, and his assessment of Pinturicchio is no exception. While he acknowledges Pinturicchio’s contribution to the art of his time and his role in major projects, Vasari ultimately sees him as a less sophisticated artist - praised only for his “transitional” status - who failed to fully adapt to the innovations that defined the Renaissance. For Vasari, Pinturicchio’s emphasis on decorative detail and his reliance on older, more linear styles prevented him from achieving the level of technical mastery that Vasari celebrated in artists like Raphael, Michelangelo, and Leonardo.

However, recent re-evaluations have rekindled interest in Pinturicchio’s contributions, appreciating his ability to merge storytelling with a refined, spiritual sensibility.

A little more eye-candy

Magnificent. Bookmarked. So much here to marvel at,to revisit. What is name of painting in which the weeping angel appears? And where does one find it?

Thank you for this terrific essay.

Not exactly Gregorian Chant, I know, but the title of this song expresses what I feel every time I visit The Sacred Images Project:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fayL1WTR1Go