Benedictine Empire - how the Holy Rule conquered Europe

Part 1: Benedictinism 101 and the early days of Benedict's monastic life with my pics and vids from Subiaco

In today’s post for all subscribers, I thought we could take a closer look at the development of what came later to be known as Benedictine monastic life, the dominant form in Europe after it was greatly boosted by the Carolingian dynasty. Earlier this week in our post for paid members, we talked about how Benedictine monasteries took a crucial role in the development of the new western European Christian civilisation launched by the coronation of Charlemagne in 800.

How did this uniquely western form of the ancient monastic principles start, grow and develop, and ultimately become, for centuries, virtually the only expression of monastic life in western Europe? We’ll take a look over the next few free subscriber posts at this fascinating and immensely important history, with its threads going back all the way to the Egyptian deserts.

The Sacred Images Project is a reader-supported publication where we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. It’s my full time job, but it’s still not bringing a full time income, so I can’t yet provide all the things I want to and am planning for. You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week. Take out a paid membership to get all three.

For $9/month you also get the second half of the weekly Friday Goodie Bag post, plus a weekly paywalled in-depth article on this great sacred patrimony, plus our Benedictine Book Club in the Substack Chat. There are also occasional extras like downloadable exclusive high resolution printable images, ebooks, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts.

If you would prefer to set up a recurring donation in an amount of your choice, or make a one-off contribution, you can do that at my studio blog. In fact, this helps me a lot, since going through the studio blog (on a different platform) means I don’t pay the Substack fee of 10%.

This is the site where I post photos of my own work as it develops. I have a shop there where some of my drawings and paintings are available for sale as prints, as well as some other items, like this little painting of St. Anthony the Great, based on a 14th century fresco in one of our churches here in Narni.

Please enjoy a browse.

Where did it really start?

When discussing the origins of Benedictine monasticism, most people instinctively think of Montecassino as the starting point. And, in one sense, that’s correct; it’s often called the birthplace of Benedictine life. But St. Benedict’s journey began much earlier, in places less prominent but equally significant.

It all began really when Benedict, the young aristocratic Roman, abandoned his secular studies in Rome, and left the city with his servant to seek the will of God in a prayerful, holy life. This led him eventually to an eremitical ascetic life of deep prayer in one of the many caves of the Apennine mountains outside Rome. He was fed there, famously, by a monk named Romanus who was only able to lower down a basket of food on a long rope, so inaccessible was the young hermit’s cave1.

Eventually, after many spiritual experiences and miracles, Benedict left his cave and began his journey south that would end at Montecassino. But along the way he founded many little places and had many adventures.

A cleft in the rock to pray: where it started

Sacro Speco Monastery is a significant site in the history of Benedictine monasticism and is located near Subiaco, Italy. Its name, which means “holy cleft” in Italian, reflects its origins and spiritual significance.

The monastery is quite difficult to get to. It clings as a series of buildings stuck to the side of an enormous sheer rock face in a part of the Lazio countryside about an hour and a half on winding back country roads from Rome. There’s no train, but bus loads of pilgrims and tourists, eager to see one of the world’s great caches of medieval art, fill the monastery’s parking lot even in February, the very bottom of the low season.

It’s REALLy remote, even today.

Sacro Speco: where history and spirituality meet

Sacro Speco was established around the 5th century at the site where St. Benedict lived as a hermit in a cave. There were already Christian ascetics or monks living in this remote area, and it’s likely for that reason Benedict settled there. This tiny cave, or “speco,” was central to his early spiritual life and served as his place of solitude and contemplation, his first determined reaching out to God.

Over time, the site evolved into a more structured monastic cenobitic (communal) monastery that only adopted the Rule of St. Benedict later, since its existence predated the work’s publication. Sacro Speco was one of the first places where Benedict’s principles were practiced in a communal setting, making it a foundational site for Benedictine life.

The monastery is renowned for its architectural and artistic treasures. The site includes a series of chapels and cells built into the rocky cliffside, incorporating the raw rock along with stone masonry creating very narrow buildings that seem to hang off the great cliff like kitchen cupboards off a wall.

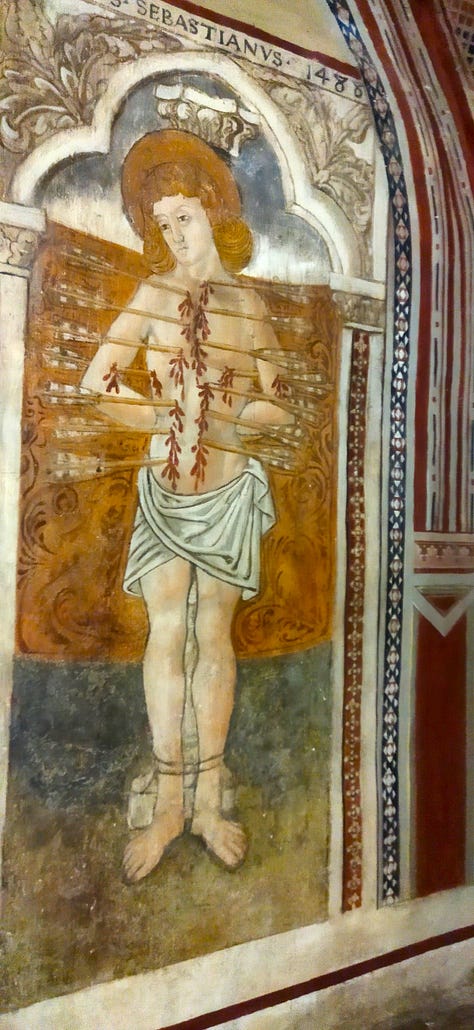

It features incredible and wonderfully preserved and maintained frescoes dating from the 13th to 15th centuries. These works serve as a kind of visual history of medieval monastic religious art and the development of western iconography.

Sacro Speco became an important pilgrimage site during the Middle Ages, attracting visitors from across Europe who sought to experience spiritual closeness to St. Benedict. It holds a special place in the history and hearts of Benedictines from its direct connection with St. Benedict’s early life and his spiritual development. Its very remoteness and rocky inaccessibility symbolises the ascetic way toward sanctification that the Benedictine life is about.

There isn’t really a “Benedictine Order”

When people refer to the Benedictine Order, they might imagine a centralized, hierarchical organization like the Franciscans or Jesuits, with a clear chain of command and a superior general overseeing all its members. But when it comes to Benedictines, that’s not quite the case. There is an Abbot Primate headquartered at the Abbey of Sant'Anselmo in Rome, but he’s more like a liaison with the papacy and curia than the head of an order. In fact, it’s more accurate to speak of monasteries that follow the Rule of St. Benedict because Benedictine monasteries are technically independent and self-governing.

The basic monastic principles expressed in the vows are consistent across Benedictine monasteries, but the way they are lived out can differ significantly from one place to another. That’s because Benedictine monasteries are autonomous, with each electing its own superiors, who govern the community without any external control. There are Benedictine “confederations” these are voluntary associations and have no canonical jurisdiction over individual houses. Nowhere in the Rule does the Rule say you have to do absolutely everything in the Rule exactly the same way. Quite the opposite.

This autonomy and adaptability allowed each foundation to address the needs of the various political and economic situations, and climatic and geographical challenges in place. Some monasteries focused on scholarship and intellectual work, some ran schools and universities, produced the stuff of the medieval theological debates, while others prioritised manual labour, hospitality, or agricultural work.

It’s all about The Rule

The core of Benedictine life, the key to the whole thing in all its diversity, is the Rule of St. Benedict, a spiritual guide written by St. Benedict of Nursia in the 6th century. This Rule has shaped the daily life of monks and nuns for over 1,500 years, outlining how they should balance prayer, work, and communal living. The Rule doesn’t envision a large, centrally managed organization; instead, it promotes self-sufficiency and local governance.

Any house of praying people, whether recognised by the hierarchy of the Catholic Church or not, can adopt the Rule and begin the life; but that’s only how you start to become a Benedictine2. In a very real sense, we should speak of Benedictinism, like monasticism more generally, as an oral tradition. One starts by deciding to start, but a beginner can only advance with instruction by masters of the life. Just doing it on your own and figuring it out as you go along is unanimously understood to be a terrible idea. You need monks, in effect, to make more monks.

Not the vows you’re used to

People are sometimes surprised to hear that the three vows of the ancient Benedictine way of monasticism aren’t “Poverty, Chastity and Obedience.”

Instead, the traditional three vows in Benedictine monastic life are stability, obedience, and conversion of life (conversatio morum3). These vows form the foundation of the Rule of St. Benedict and encapsulate the essence of monastic commitment.

Stability

Benedictine monks and nuns take a vow of stability, committing themselves to remain in the same community for life. This vow fosters a deep sense of permanence and rootedness within the monastic community, as well as a lifelong dedication to seeking God in a specific place and through a particular group of people. It allows the individual to grow spiritually through the ups and downs of daily communal life, forming a strong connection to both the monastery and its surrounding local community.

Obedience

The vow of obedience is central to the Benedictine way of life. It means listening attentively (“obedience” comes from the Latin ob-audire, “to listen”) most importantly to God, but it’s understood that the “voice” of God in the day to day life of a monk comes to him through his superiors. And he must “listen” to his brothers in the community. Benedictine obedience is not blind, as the idea later became under the Jesuit corruption, nor is it passive; it involves a prayerful responsiveness to God’s will as revealed in Scripture, the Rule of St. Benedict, and through one’s brothers or sisters in the monastery. Obedience teaches humility and aligns personal will with the greater good of the community.

Conversatio Morum (Conversion of Life)

The vow of conversatio morum, often translated as conversion of life or fidelity to monastic life, is the commitment to ongoing interior transformation. It’s a promise to constantly turn toward God and grow in holiness throughout one’s life. This vow encapsulates the continuous process of spiritual renewal, self-discipline, and openness to grace. It embraces the whole monastic way of life, prayer, work, study, and community.

The Early Years: St. Benedict’s Foundations at Subiaco

Before founding Monte Cassino, St. Benedict of Nursia spent several years establishing smaller monastic communities in and near Subiaco4. But this period of activity followed a time (we don’t know how long, but these things take a while so at least a few years) of a solitary contemplative life, where he sought God in silence and prayer living in the cave we saw above. As always happens, during this period, Benedict’s reputation for holiness spread, and many came seeking his guidance.

Careful what you ask for

In the Dialogues by Pope Gregory I, there is a notable incident from this period, involving an attempted poisoning. A group of monks from a neighbouring monastery had asked the saint to come and be their superior to help them reform their way of life. But as so often happens, the reforms weren’t to their liking and they plotted to poison him.

Having now taken on him the charge of the Abbey, he took order that regular life should be observed, so that none of them could, as before they used, through unlawful acts decline from the path of holy conversation, either on the one side or on the other: which the monks perceiving, they fell into a great rage, accusing themselves that ever they desired him to be their Abbot, seeing their crooked conditions could not endure his virtuous kind of government. Therefore, when they saw that under him they could not live in unlawful sort, and were loath to leave their former conversation, and found it hard to be enforced with old minds to meditate and think on new things: and because the life of virtuous men is always grievous to those that be of wicked conditions, some of them began to devise, how they might rid him out of the way.

They prepared a cup of poisoned wine and presented it to St. Benedict. Aware of their plot, Benedict made the sign of the cross over the cup, and miraculously, the cup shattered. Benedict remonstrated with the ungrateful monks, and left to go back to his cave.

But the incident, of course, spread his reputation far and wide.

Around 520, Benedict began organising his followers into twelve small monastic communities near Subiaco. Each of these early monasteries housed about twelve monks and was led by a prior. This number—twelve—was symbolic, reflecting the number of Christ's apostles and the communal nature of their life. These early communities adhered to a general monastic rule, one focused on prayer, asceticism, and communal living, but it wasn’t yet the fully developed Rule of St. Benedict we associate with him today.

While these early monasteries laid the groundwork for Benedictine life, they were not centralized. They operated more like independent satellite communities, united by a common desire to live out their faith in an intensely committed way, but not yet by the formalized monastic structure that Benedict would later create.

The Turning Point: The Founding of Montecassino

In 529 AD, after spending several years at Subiaco and encountering opposition from local clergy, St. Benedict moved south and founded Montecassino. This was the pivotal moment in Benedict’s monastic vision. Montecassino was not just another small community; it was the first large, centralized monastery where Benedict could fully realize his vision of monastic life.

Montecassino was to become the model for future monastic foundations. It was here that Benedict wrote his Rule, which was to be adopted nearly universally. It was popular for its rejection of the extreme asceticism of earlier forms of monasticism, advocating instead for stability, moderation, and hospitality values that could be lived out consistently over a lifetime by even the weakest.

Unlike the smaller and somewhat fragmented communities at Subiaco, Montecassino was a single, unified monastery, with a central authority and a formal rule that governed all aspects of monastic life. This was where Benedict's vision of monasticism took on a lasting form, one that would spread far beyond Italy and shape the spiritual landscape of Europe.

Montecassino continues to hold symbolic importance for Benedictines. It wasn’t just another isolated monastery but became a centre of learning, prayer, and hospitality, drawing people from all over the peninsula and served as a model for future monastic communities throughout Europe.

All the details we have of the life of St. Benedict come from the section on his life by Pope St. Gregory the Great in his Dialogues. Gregory wrote about other saints in his great book, including the first Christian bishop of Narni, St. Giovenale (Juvenal) who came here in the 4th century and founded a monastery. The full text can be found here.

The flip side being that any group calling themselves Benedictine who don’t follow and study the Rule aren’t.

Often incorrectly translated as “conversion of manners” - which doesn’t work well with modern vernacular English, sounding as though Benedictine life is about knowing which fork to use and to remember to write thank you notes.

Subiaco itself is the town that grew up near the monastery, something that nearly always happens, as the lay people gravitating to Clear Creek Oklahoma will know.

Very nice summary of Benedictine spirituality and the beginnings. So glad you got to go there and to share it with us!

Deo Gratias!