Myth of Modern Progress and the Rejection of Christian Roots in Art History

It comes down to post-Protestant, Enlightenment anti-Catholic bigotry

The Lens We Look Through

When we think about the history of Western art, we don’t often question the underlying story we’ve been taught. We have a kind of grand narrative about it, that we take for granted: art “evolved” from “primitive” 2-dimensional Byzantine and medieval forms into the elevated and technically sophisticated visual naturalism and exalted and enlightened humanism of the Renaissance, which we’re told was the absolute pinnacle of artistic achievement. Art is only “good” when it “looks real.”

But have you ever stopped to ask who wrote that story and why? Who decided that the Renaissance and humanistic Naturalism was the peak, and everything before it was just a prelude to that glory? What criteria did they use to make that judgment, and what might they have left out? This is the field of study called “historiography” in academia, and it’s important to understand it. We tend to take these narratives as though they were handed down to us from heaven when they are in fact simply ideas of individual human beings, working out of their specific historical and cultural backgrounds.

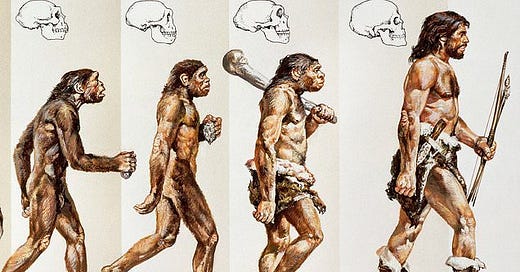

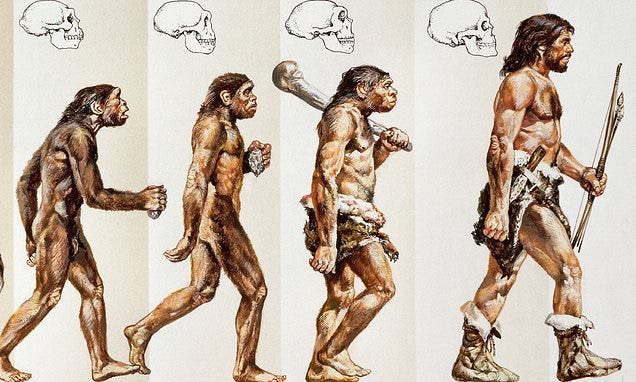

When we think about art history, we’re often presented with a linear historical progression of styles and movements. I know we all remember those illustrations of human evolution we used to get in school books: a series of figures march forward through ancient history, from Homo habilis, through Neanderthals, to finally become Homo sapiens. It’s a neat, tidy story that suggests everything was always progressing in an orderly, linear way toward a perfect endpoint. And it’s one that has been thoroughly debunked.

But this way of thinking about art history, often called the “Whig” narrative, comes from the same 18th and 19th century mindset that crafted the evolutionary narrative. It assumes that history is a steady march toward improvement, willed by the cosmos, toward something greater and more enlightened. As with the simplistic story of human evolution, this approach leaves a lot out, glossing over the multi-layered complexity, specific cultural developments and achievements, and most of all spiritual value of earlier forms of art, particularly Christian sacred art.

Looking at the characters who cooked up these ideas, one thing is striking: their deep-set, systematic and ideological anti-Catholicism.

In today’s post for paid subscribers we’re going to dive into the “historiography” - the philosophy of Christian art history, the ideas behind the broadly accepted narrative frame. Historiography is the study of how history is written and interpreted; the methods, and biases, that historians use to construct narrative frameworks. It’s essentially the history of history, examining the different ways that scholars have interpreted art and all its developments through particular interpretive lenses.

In this case, we’re going to look at how we arrived at the “Whig” narrative, who the key figures were, and what biases they introduced into their interpretations that have been absorbed by the culture as a whole.

Related posts:

How the West Betrayed Its Own Sacred Tradition

Lies the Renaissance told you P 1.

Lies the Renaissance told you P2.

Northern Gothic Devotion vs. Renaissance Humanism P 1.

Northern Gothic Devotion vs. Renaissance Humanism P2.

From Giotto to Lovecraft: the long, slow, inexorable slope of materialist metaphysics. Part 3 of our series Gothic Devotion vs. Renaissance Humanism

The Sacred Images Project is a reader-supported publication where we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. It’s my full time job, but it’s still not bringing a full time income, so I can’t yet provide all the things I want to and am planning for. You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week.

For $9/month you also get the second half of the weekly Goodie Bag post, plus a weekly paywalled in-depth article on this great sacred patrimony, plus our Benedictine Book Club in the Substack Chat. There are also occasional extras like downloadable exclusive high resolution printable images, ebooks, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts.

If you would prefer to set up a recurring donation in an amount of your choice, or make a one-off contribution, you can do that at my studio blog. Of course, anyone setting up a monthly patronage for US $9/month or more will get a complimentary subscription to the paid section here.

This helps me a lot because the patronages through the studio blog are not subject to the 10% Substack fee:

This is the site where I post photos of my own work as it develops. I have a shop there where some of my drawings and paintings are available for sale as prints, as well as some other items.

Like this little painting I did earlier this year of St. Anthony the Great, father of all monks, inspired by one of the 14th century frescoes in one of our churches here in Narni.

Subscribe to join us below.