Buried treasure: the golden hoard of Sutton Hoo

Anglo-Saxon society was wealthy and sophisticated

Treasure in the back garden

In the summer of 1938, as the world watched the dark clouds of war growing on the horizon, an English widow named Edith Pretty stood at the edge of her estate, gazing at the mysterious mounds that rose like silent sentinels across her land. Her home, a stately red-brick house in the rolling Suffolk countryside, overlooked the quiet bends of the River Deben. The estate, with its broad meadows and ancient oaks, had an air of timelessness, a place where the past still whispered its secrets in lost languages from beneath the soil.

Pretty, then 53 years old, was not just a landowner with a passing interest in history and archaeology; she had travelled extensively in her youth, visiting archaeological sites in Egypt and the Middle East. She was an independent and strong-willed woman, one of the first female magistrates1, and had an enduring fascination with history and the unknown - being interested in Spiritualism, a fashion of the time in her class. Following the death of her husband in 1934, she took charge of the estate and was raising her young son, Robert, when she decided to investigate the mounds further.

For years, she had felt an unshakable sense of curiosity about these mounds. Stories of ancient warriors, treasure, and lost kings swirled through local folklore, and she often found herself wondering, what if the stories were true?

Though she was a woman of her time, and living in a world that prized modernity and materialism over myth, something in her heart told her that the past still lingered beneath the rolling earth of her Suffolk home. Encouraged by her own intuition and the gentle urgings of local historians, she hired Basil Brown, an unassuming but brilliant self-taught archaeologist, to investigate.

What he uncovered would become one of the most astonishing archaeological finds of the 20th century, the English equivalent of the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun; the Sutton Hoo treasure, a burial fit for a king, dazzling in its artistry and mystery.

In todays post for all subscribers, we’ll continue looking at the art of the “Barbarian” western Europe after the fall of the Western Empire in 476. Specifically we’ll take a look at one of the most extraordinary and famous treasures of Anglo-Saxon art and craftsmanship, the Sutton Hoo Hoard. This astonishing ship burial, unearthed in 1939 in the rolling countryside of Suffolk, reveals a completely different Britain; world of ancient kings, warriors, and intricate artistry that reshapes our understanding of early medieval Britain.

At the Sacred Images Project we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. The publication is supported by subscriptions, so apart from plugging my shop, there is no advertising or pop-ups. It’s my full time job, but it’s still not bringing a full time income, so I can’t yet provide all the things I want to and am planning for.

You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week.

For $9/month you also get the second half of the third post, plus a weekly paywalled in-depth article on our great sacred patrimony. There are also occasional extras like downloadable exclusive high resolution printable images, ebooks, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts.

From the shop: since we’re going to be talking about the opening of the monastic tradition in Egypt in this section of the Big Editorial Plan, this might be a good time for a little print of St. Anthony of the Desert, the father of monks. This is a little egg tempera painting I did based on a 14th century fresco in one of Narni’s medieval churches. The original is sold, but you can have a high quality art print either on a wood panel, or museum quality paper.

I think it would make an elegant addition to a prayer corner or mantel.

You can order one, and lots of other nice things, at the shop, here:

What Was Discovered?

Sutton Hoo is the site of an Anglo-Saxon ship burial dating to the early 7th century, a time when Britain had long since transitioned from Roman rule and the future kingdoms of England were in their infancy. Though it is impossible to confirm, scholars have speculated that it might have been the burial of King Rædwald, the 7th Century Anglo-Saxon ruler of East Anglia.

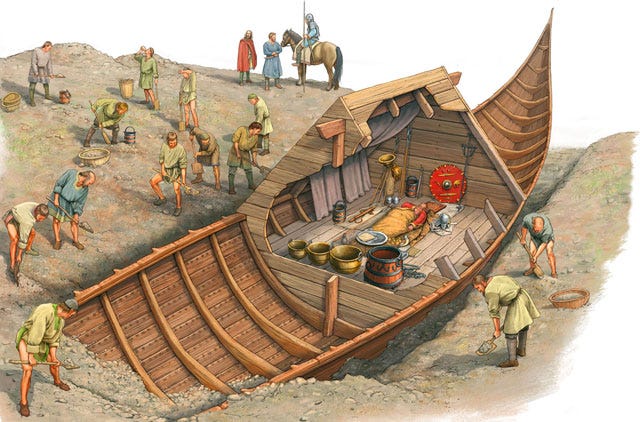

Mound 1 contained an entire Anglo-Saxon wooden ship, 27 metres (89 ft) long, which had seen use on the seas and been repaired. In the centre of the ship was a chamber containing the most extraordinary collection of jewellery, tools, clothing, drinking and feasting vessels, and richly decorated ceremonial weapons and armour, including the famous helmet.

The British Museum has a full catalogue of 8,347 objects found at the Sutton Hoo site, from fabulous golden jewellery to minute fragments of animal remains2.

Sutton Hoo Helmet – A masterpiece of early medieval craftsmanship, featuring a distinctive iron and bronze face mask with stylized eyebrows and a dragon-like nose.

Sword and Weapons – A finely decorated sword with gold and garnet fittings, along with a collection of spears and a shield boss, indicating the status of a high-ranking warrior or king.

Gold Belt Buckle – A large, intricately decorated gold buckle, demonstrating remarkable Anglo-Saxon metalworking skill.

Enamel belt buckles - rectangular gold and garnet cloisonné

Shoulder Clasps – Gold and garnet cloisonné shoulder clasps, likely part of ceremonial or battle attire.

Purse Lid – An elaborately decorated gold and enamel purse lid, originally containing gold coins from the Merovingian kingdom, suggesting trade or diplomatic ties.

Silverware – Byzantine silver bowls and spoons, possibly diplomatic gifts or imported luxuries.

Drinking horns, wood and ceramic bottles and feasting equipment – Items associated with elite banqueting, reflecting the warrior-aristocracy culture.

Lyre (Musical Instrument) – Fragments of a wooden lyre, hinting at the role of music in Anglo-Saxon courtly life.

Gold and Garnet Fittings – Various sword, scabbard, and horse harness fittings.

Ship Burial Structure – The remains of a 90-foot-long wooden ship, reinforcing links to Scandinavian burial traditions.

You can scroll through the full catalogue here.

Among the most famous finds was the Sutton Hoo helmet, a stunning iron and tinned-bronze mask with stylized eyebrows, a dragon-like nose, and cheek guards resembling wings. This iconic piece, now displayed in the British Museum, has become the very image of early medieval England, a warrior society blending pagan warrior ethos with emerging Christian influences.

The Cultural Background of an Anglo-Saxon Ship Burial

Ship burials were not common in Anglo-Saxon England, being more typical of Scandinavian societies. The practice of burying rulers or warriors in ships with grave goods symbolized their journey to the afterlife and their status as leaders even beyond death. The presence of such a burial at Sutton Hoo suggests strong cultural and trade links with the broader Germanic and Nordic world.

The Sutton Hoo burial shows us a transitional period in England’s religious landscape. Rædwald himself is thought to have maintained both Christian and pagan religious practices, and the burial follows a pagan tradition, though some of the grave goods hint at Christian influence, including a large number of Byzantine objects. The blending of these traditions speaks to a society in flux, balancing old beliefs with the encroaching tide of Christianity.

Furthermore, the craftsmanship of the grave goods reveals the sophistication of early medieval England. The goldsmithing, intricate cloisonné work, and the fine detailing of the metal artifacts suggest a highly developed artisan culture - with an economic base secure enough to spend time and resources on high-end luxury goods - connected through trade to far-reaching parts of Europe and beyond.

Many of the objects found at Sutton Hoo appear to have been traded from far beyond England’s shores. The presence of Byzantine silverware, luxurious gold-and-garnet ornaments, and even artifacts that may have originated in Egypt suggests that the Anglo-Saxon elite were connected to a vast and sophisticated trade network. These goods could have arrived through commerce, diplomacy, or tribute, demonstrating the wealth and political influence of East Anglia’s ruling class. Rather than existing in isolation, early medieval England was deeply entwined with the broader economic and cultural currents of Europe and the Mediterranean world.

Why Does Sutton Hoo Matter?

A close analysis of some Anglo-Saxon objects showed museum curators a previously unexpected level of sophistication of technical ability of the 7th century metalsmiths.

The discovery of Sutton Hoo shattered the old myth that the so-called Dark Ages were culturally stagnant, primitive or unsophisticated. Until the discovery of the Staffordshire Hoard in 2009, Sutton Hoo remained unparalleled in its insight into the wealth and craftsmanship of early medieval England. The Staffordshire Hoard, an immense collection of Anglo-Saxon gold and silver metalwork, reinforced the extraordinary artistry and power of the period, offering another astonishing glimpse into the so-called Dark Ages.

These finds have revealed a sophisticated, cosmopolitan, warrior-led society with vast trade networks stretching from Scandinavia to the Mediterranean. The goldwork rivals anything from Byzantium, and the ship burial itself echoes the grand funerary traditions of the Norse and Germanic peoples.

2020 film, The Dig, depicted the Sutton Hoo discovery.

The excavation itself has become the stuff of legends, and spawned a small subculture of hopeful metal detectorists and amateur archaeology enthusiasts who comb the British landscape hoping for another major discovery.

Many have regularly turned up interesting finds - coins, brooches, rings and the occasional fragment of ancient weaponry - but nothing approaching the scale of the Sutton Hoo hoard was discovered in the 20th century. The sheer magnitude of what Edith Pretty and Basil Brown uncovered in 1939 remains unparalleled in British archaeology.

The legend of Sutton Hoo has also inspired novelists, filmmakers, and scholars, each seeking to capture the moment when the past re-emerged from the soil. The burial’s striking resemblance to the heroic funeral traditions described in Beowulf only adds to its mystique.

More work to be done

Sutton Hoo might be appearing more often in the archaeology news in the next few years. The National Trust opened further excavations in January this year. Angus Wainwright, a National Trust archaeologist said there is still a great deal to learn about the site. A geophysical survey of the Garden Field had identified “mysterious geophysical anomalies” and questions have long been asked about the large cache of prehistoric flint knapped tools found at the site.

The Garden Field section of the site “has an extraordinary amount of archaeology in it, from prehistoric fields and possible burial mounds through to Roman settlements and an Anglo-Saxon cemetery, but who knows what else may be hidden there,” Wainwright said.

This doesn’t mean she was a judge in the formal legal sense. In England and Wales, magistrates are trained volunteers, selected from the local community but very often from the landowning class, who deal with a wide range of local criminal and civil proceedings.

The catalogue includes some much older objects, including early bronze age implements, and even some knapped flint objects like arrow heads that are dated to the Neolithic.

Sutton Hoo is truly fabulous. When I was teaching my students "Beowulf" last fall, I introduced them to Sutton Hoo. They were astounded, and rightly so in my opinion. The artistry and craftsmanship on some of those items is unparalleled.