Celtic crosses and Saxon monasteries: how island art and monks helped shape Christian Europe

Faith and art meet at Lindisfarne and Kells

The one we’ve all been waiting for…

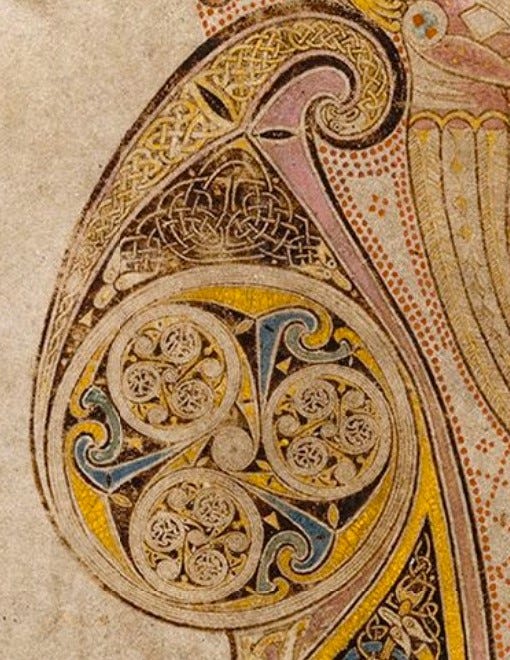

When we think of early Irish and British monks of the early period of Christianity in Britain and Ireland, we think of dimly lit scriptoria of ancient monasteries in a rainy, green and mist-covered landscape. And when we think of Celtic and Anglo-Saxon sacred art, the mind’s eye always goes to the intricate, mathematically precise knotwork, swirling and spirals patterns, and mystical symbols in manuscripts, metalwork and stone carving.

In today’s post for all subscribers, we’re going to start to look at these extraordinary images, their cultural and spiritual background and meaning, and how the style ended up incorporated into the flowering of continental art we call the Carolingian Renaissance.

Last week we talked about how the monasteries began to flourish under the protection and encouragement of the new western emperor, Charles the Great, and how that allowed the Rule of St. Benedict to become the standard text across western Europe to found monastic life, and consequently the secular edifices that grew up around it.

Today we’re going even further west…

The Sacred Images Project is a reader-supported publication where we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. It’s my full time job, but it’s still not bringing a full time income, so I can’t yet provide all the things I want to and am planning for. You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week. Take out a paid membership to get all three.

For $9/month you also get the second half of the weekly Friday Goodie Bag post, plus a weekly paywalled in-depth article on this great sacred patrimony, plus our Benedictine Book Club in the Substack Chat. There are also occasional extras like downloadable exclusive high resolution printable images, ebooks, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts.

If you would prefer to set up a recurring donation in an amount of your choice, or make a one-off contribution, you can do that at my studio blog. In fact, this helps me a lot, since going through the studio blog (on a different platform) means I don’t pay the Substack fee of 10%.

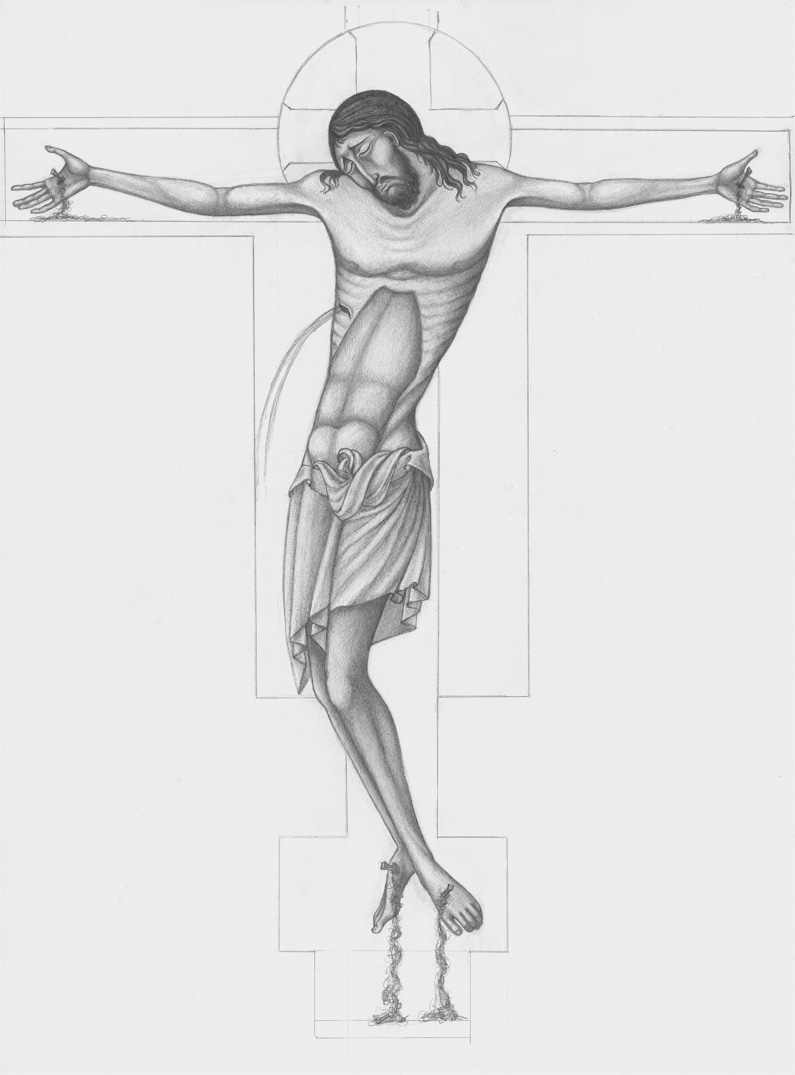

This is the site where I post photos of my own work as it develops. I also have a shop there where some of my drawings and paintings are available for sale as prints, as well as some other items. Like my graphite drawing of the crucified Christ, in the style of the 13th century Umbrian panel crucifixes.

Celtic and Pre-Christian Roots: who were the Celts?

The various peoples we commonly group together as “the Celts” were a diverse group of tribal societies that flourished across Europe from the late Bronze Age into the early Iron Age. Their origins can be traced back to the Hallstatt culture (around 1200-500 BC) in the region of modern-day Austria, Switzerland, and southern Germany. This area, rich in salt mines and metal ore, became a hub of trade and cultural exchange, allowing the development of what would become distinctively “Celtic” societies.

The La Tène culture (Iron Age, circa 500-1 BC-AD) is associated with the height of Celtic civilization, as the tribes spread widely across Northern Europe, from the British Isles to as far east as Galatia in modern Turkey. Celtic societies were organized into tribal groups led by chieftains and warrior elites, with a strong emphasis on kinship and honour. They were renowned for their skills in metalworking, particularly in iron and gold, and their distinctive art forms, including intricate knotwork and swirling designs that adorned everything from weapons and jewellery to monumental stone carvings.

Christian Influence: The Arrival of Christianity in the British Isles

Early Contacts and Roman Influence (1st-4th Centuries AD):

Christianity arrives during the Roman occupation. Roman soldiers, traders, slaves and settlers brought Mediterranean Christianity with them.

By the 4th century AD, evidence of Christian communities, such as churches and burial sites, began to appear, particularly in Romanised towns, even among the upper classes.

The Mission of St. Patrick (5th Century AD):

St. Patrick, originally from Roman Britain, spread of Christianity in Ireland after the Roman retreat in the 5th century. After escaping from slavery in Ireland, he returned as a missionary, establishing churches, converting local chieftains, and laying the foundations for Irish monasticism.

The Gregorian Mission (6th-7th Centuries AD):

In 597 AD, Pope Gregory the Great sent St. Augustine of Canterbury and a group of monks to convert the Anglo-Saxons - newly arrived pagan settlers - in southern England. This mission led to the establishment of the first Christian kingdom in Kent.

The mission's success prompted further conversions among Anglo-Saxon rulers and the foundation of important monastic centres, including Canterbury and York.

Celtic Monasticism and the Irish Missions:

Meanwhile, in Ireland, monasticism flourished independently of Rome, producing influential figures such as St. Columba, who established the monastery on Iona, and St. Aidan, who founded the monastery at Lindisfarne.

Irish monks were instrumental in re-Christianising parts of Britain and Europe, travelling as missionaries and founding monasteries that became centres of learning and art.

Synod of Whitby (664 AD):

The Synod of Whitby was a crucial meeting that resolved differences between Roman and Celtic Christian practices in England, aligning the English Church more closely with Roman customs. This unification helped consolidate Christianity across the British Isles.

The Book of Kells: the greatest Irish Christian national treasure

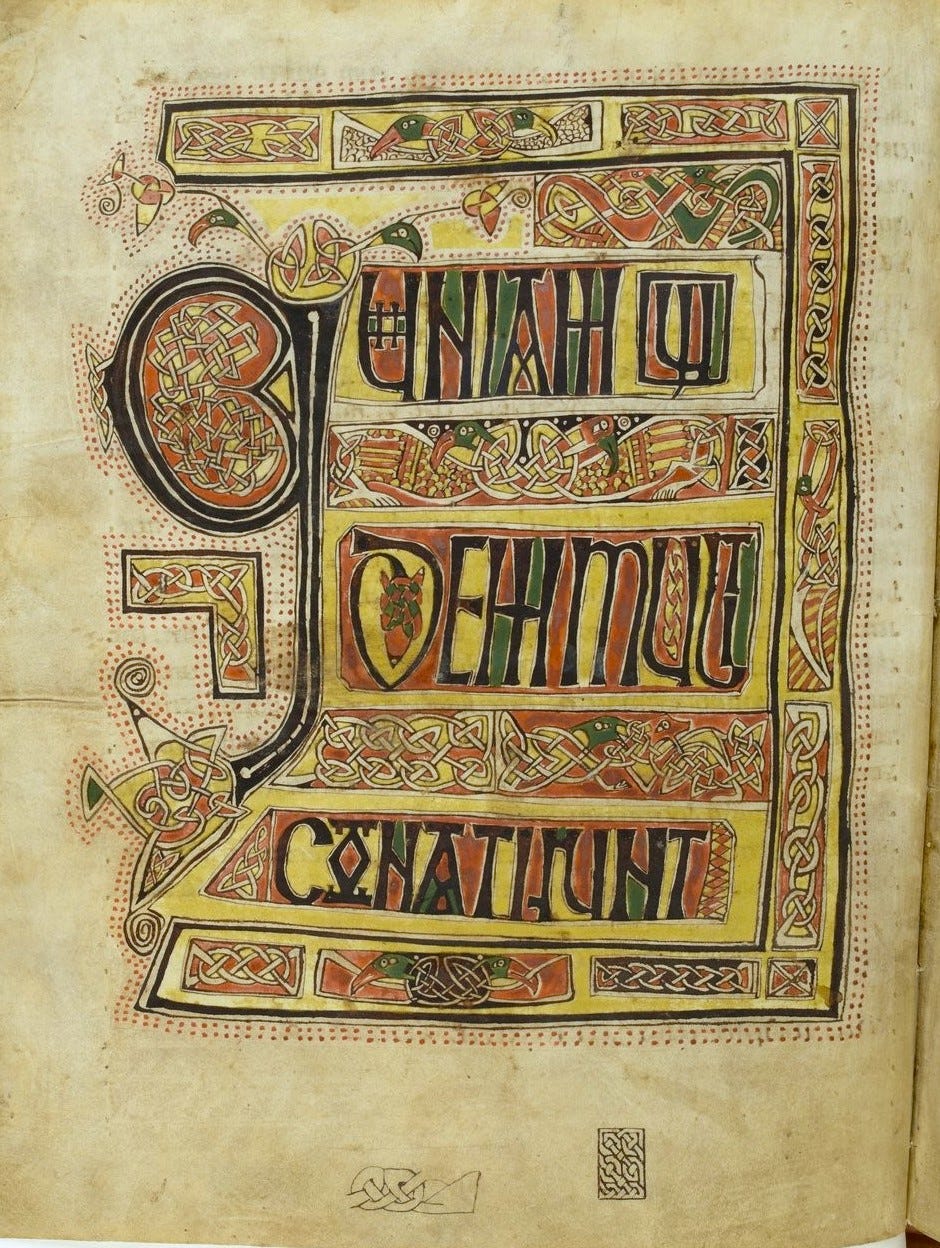

The Book of Kells (c. 800) is an illuminated manuscript Gospel book in Latin, containing the four Gospels of the New Testament together with various prefatory texts and tables.

There is some uncertainty about its origins. It is thought that the Book of Kells may have first worked on at the Columban monastery on the island of Iona off the west coast of Scotland, and was continued, after Viking raids, at the monastery of Kells. Kells Abbey was plundered and pillaged by Vikings many times in the 10th century so it is doubly surprising it survived.

The Book of Kells remained in Ireland throughout the Reformation period under Henry VIII, when many religious artefacts were at risk, but there are no records indicating that the it was removed from Ireland for safekeeping.

The Book of Kells was kept at the Abbey of Kells in County Meath until it was stolen in 1007 AD. It was later recovered, missing its gold cover and some pages. By the 12th century, it was restored to Kells.

In 1654, during the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland, the Book of Kells was moved to Dublin for safekeeping. It was eventually given to Trinity College Dublin in 1661, where it has been ever since, housed in the Trinity College Library.

Celtic sacred art; the intertwining of heavenly and earthly realities

From the fascinating and astonishing illuminations of the Book of Kells to the monumental stone crosses that dot the Irish countryside, these artworks are visual sermons, embodying the spiritual fervour and unique creative genius of this Christianised “barbarous” culture.

Celtic interlacing and knotwork, prominent in early Christian art from the British Isles, are more than decorative motifs; they carry deep symbolic meanings that reflect Christian theology. The endless, looping lines of these intricate designs are often interpreted as symbols of eternity, reflecting the Christian belief in eternal life and the infinite nature of God.

The unbroken paths of the knots represent the wholistic Celtic approach to the perpetual journey of the soul in which the divine presence and all creation are intimately connected within the plan of salvation. The cyclical nature of the designs reflects Christian beliefs in resurrection and the promise of life after death but at the same time a deep connectedness with the natural world.

Celtic and Saxon distinctions

Irish Celtic art and Anglo-Saxon art, though both part of the Insular art tradition, exhibit distinct differences. Irish Celtic art is deeply connected to the native Celtic traditions of Ireland, drawing heavily from earlier La Tène styles characterised by swirling, abstract patterns and zoomorphic designs. This artistic language was seamlessly integrated with Christian themes, resulting in highly ornamental works featuring intricate knotwork, spirals, and crosses.

In contrast, Anglo-Saxon art developed within the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms of England and blended Germanic traditions with Mediterranean Roman, and Byzantine influences.

In manuscript illumination, Irish and Anglo-Saxon differences are particularly pronounced. Irish manuscripts like the Book of Kells and the Book of Durrow are famed for their dense, decorative pages filled with elaborate knotwork, spirals, and vibrant colours that prioritise ornamental beauty over narrative clarity.

Anglo-Saxon manuscripts, such as the Lindisfarne Gospels and the Aethelstan Psalter pictured above, maintain similar intricate designs but place greater emphasis on the depiction of human figures and narrative scenes, with a clearer sense of organisation and framed panels that guide the viewer through the artwork. This reflects a balance between abstraction and narrative that is more pronounced in Anglo-Saxon works than in the intensely symbolic Celtic images.

Irish metalwork, seen in treasures like the Tara Brooch and the Ardagh Chalice, features complex filigree, inlaid enamels, and designs that weave animals and human figures into the knotwork, often with a strong monastic and religious focus.

Anglo-Saxon metalwork, exemplified by the treasures from Sutton Hoo and the Staffordshire Hoard, is marked by a more geometric patterns. While both traditions are deeply religious, Anglo-Saxon art also includes a significant number of secular items, indicating the broader cultural scope and transitional nature of Anglo-Saxon society as it moved from paganism to Christianity.

The Secret of Kells

I am never going to get tired of recommending this astonishing animated film, The Secret of Kells, which has been uploaded in its entirety to YouTube. I seriously don’t think I’ve ever seen a more beautiful piece of cinematic art.

There are some scary bits - it’s about the Vikings invading Ireland - so I’d review it first and be judicious about young children watching it.

Life in an Anglo-Saxon house

Not necessarily nasty, brutish and short - Anglo-Saxon society was deeply committed to the rule of law. But definitely chilly, damp and muddy.

Experimental archaeology: guy builds an Anglo-Saxon house. It gives you an idea what life must have been like for ordinary people after the end of the Roman “occupation”. What have the Romans ever done for us, eh? Well, stone floors might be nice.

Celtic and Anglo-Saxon Christianity goes to the Continent

Christianity had been growing in the British Isles - especially monasticism - for several centuries before the first missionaries began crossing the Channel to continental Europe. As monks and missionaries journeyed from the Isles across the Channel to the heart of Carolingian Europe, their faith and the vibrant, living tradition of Insular monastic art would leave an indelible mark on the continent’s sacred landscape.

Notable Celtic and Anglo-Saxon missionaries who journeyed from the British Isles to continental Europe during the early Carolingian period:

St. Columbanus (543–615): An Irish missionary who founded several monasteries in modern-day France, Switzerland, and Italy, including Luxeuil and Bobbio. Columbanus was known for his strict monastic rule and his writings which had a significant influence on the spread of Irish monasticism and culture in Europe.

St. Gall (c. 550–645): A disciple of St. Columbanus, St. Gall was an Irish missionary who accompanied Columbanus on his travels. He eventually settled in what is now Switzerland, where he founded the Abbey of St. Gall, which became a renowned centre of learning and artistic production after it was enlarged by Charlemagne.

St. Boniface (c. 675–754): An Anglo-Saxon missionary from Wessex, St. Boniface is often called the “Apostle of the Germans” for his work in converting the Germanic tribes and reforming the Frankish Church. His efforts were instrumental in integrating the Church in northern Europe more closely with the Roman papacy.

St. Willibrord (c. 658–739): Another Anglo-Saxon missionary, Willibrord was a leading figure in the Christianisation of the Frisians in the Netherlands and northwestern Germany. He founded the Abbey of Echternach, which became a major centre of missionary activity and a conduit for Insular art and culture.

St. Pirmin (c. 670–753): A Visigoth-born missionary of Anglo-Saxon descent, St. Pirmin was active in the regions of Alsace and Alemannia (southwestern Germany). He founded several monasteries, including Reichenau, which became a key centre for the Carolingian Renaissance and the preservation of Insular artistic traditions.

We could keep going all night and all day tomorrow and into next week diving down every Hiberno-Saxon/Insular rabbit hole, but should probably stop here. We’re pencilled in for September 25th, to return to the Islands to meet Sts. Oswald, Hilda and Cuthbert.

Thanks Hilary for this post. I managed to watch the Kells animation last night. While it is undoubtedly beautiful, quite extraordinary, I was fundamentally disappointed. It’s the book of Kells and indeed Celtic Christianity purged of Christ, replaced instead by the vibe of “hope” and “light”. I found it as much neo-pagan as Christian. A common theme within contemporary Ireland, unfortunately. But yes, the artistic expression is superb.

Wow, that wattle house construction was very impressive. Probably very snug in those days, but a bit too dark and damp for me! The Book of Kells is amazing. I had seen the video while doing a free course about the book through Trinity College some years ago. Amazing. I love how most of New Testament figures have blond curly Celtish hair.