Chora mosque: how to symbolically re-conquer and subjugate Christianity

An artistic treasure of inestimable preciousness under threat?

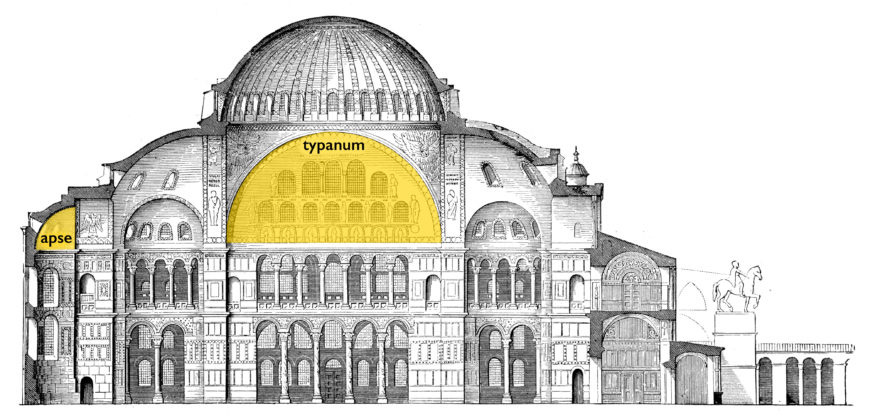

If I asked you what’s the most important repository of Byzantine art in the world, you might say Hagia Sophia in Constantinop… Istanbul.

The mosaics Hagia Sophia have mostly survived the centuries of calamitous wars and Islamic occupation, with many restorations, and are regarded around the world as the most important repository of early and middle Byzantine art in the world, not only for their artistic quality, but for their historic importance.

Likely for this reason, four years ago, Turkish president and would-be Caliph, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan announced that after being a museum and UNESCO world heritage site since the 1930s, the church that had been the centre of the Byzantine Christian world, would be turned back into an active Muslim mosque.

In 2019, when the world was somewhat distracted, UNESCO wrote to the Turkish government expressing “concerns” when it was announced that Hagia Sophia would return to active use as a mosque.

They asked for assurances that no changes would be made to “sites on the heritage list…that would harm the universal values of those sites. According to UNESCO’s statement, any changes must be reported to UNESCO in advance and if necessary, they should also be reviewed by the World Heritage Committee.

Unfortunately, it was precisely this sort of demand from the kāfir community that Erdogan, promoting himself as an Islamic leader opposing the ideological incursions of the dar al-harb, could not politically afford to allow. The re-islamicisation of Hagia Sophia was indeed a signal to the infidel world. Those whose culture, history and geography make it harder to forget the past, Greece and Russia primarily, identified it as a political signal, an attack on their Christian heritage and a step towards increased persecution of Christian populations in Turkey and Islamic countries in general.

If you’d like to see my work learning Byzantine and other traditional forms of Christian sacred art as a painter, or make a direct one-off donation, click on my studio blog:

Hagia Sophia: A Brief History

532-537 CE: Construction completed under Byzantine Emperor Justinian I, serving as the Christian cathedral of Constantinople.

1000 years: Major religious and spiritual centre for the Eastern Church.

1204: Converted to a Latin Catholic church during the Fourth Crusade.

1261: Reclaimed by the Eastern Orthodox Church.

1453: Ottoman conquest of Constantinople, converted to a mosque by Mehmed the Conqueror.

1616: Loses its status as the principal mosque after Sultan Ahmed Mosque construction.

1931: Secularization of the Turkish state, conversion to a museum.

2020: Reverted to a mosque.

After the conquest of Constantinople in 1453, the building was immediately prepared for Islamic use. Christian treasures were removed but the sultan did not allow the destruction of the mosaics. However, since Muslim religion prohibited figurative art, he ordered them to be covered with a thin layer of lime.

Even if we don’t know a lot about it, Hagia Sophia means something known and important to all apostolic Christians.

But what if I started talking about “Chora”?

The Chora

Today we are confronted with another Islamic supremacist political “flex” with the announcement from the Erdogan government that the Chora monastic church, also known as the Kariye Museum, is under threat, with plans to turn it to Islamic use in just a few weeks. Chora will open its gates on February 23 as a mosque for Friday prayers, the Turkish daily reports.

Greek President Katerina Sakellaropoulou called Erdogan’s decision to convert the church to a mosque “an act of symbolic violence dictated by political arrogance.” The President said that it is an act of “cultural insecurity and religious intolerance, which condemns a treasure trove of Christian art and cultural nobility to obscurity.”

The Turkish newspaper Yeni Şafak reports that the long-term restoration of the Chora church has ended.

“The historic mosque, furnished with specially designed red carpets, is scheduled to open for worship on Friday, February 23. On the other hand, it became known that the mosaics and frescoes in the historic mosque were preserved during the restoration and will be open to visitors,”

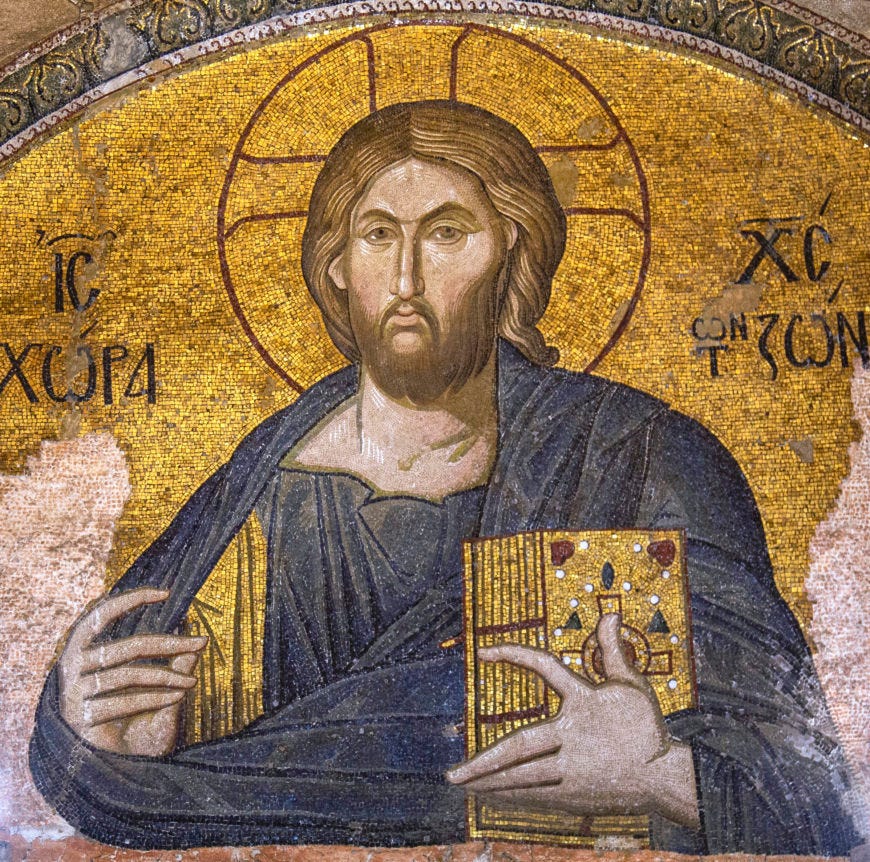

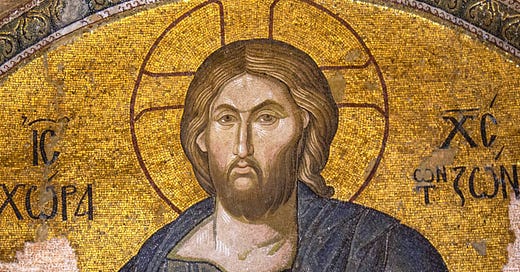

The Chora monastery church, one of the oldest and most important in the Christian world, is the home of the other most important set of Byzantine frescos and mosaics surviving in the world today, dating to the later era of the style.

Chora Monastery Church: A Brief History

4th century CE: Founded as a monastery complex outside Constantinople's walls.

11th-12th centuries: Rebuilt and expanded under Theodore Metochites, a prominent statesman and scholar.

1320s: Adorned with stunning mosaics and frescos depicting biblical scenes and theological concepts. These works are considered masterpieces of Byzantine art.

1453: Ottoman conquest of Constantinople. Church converted into a mosque, some mosaics covered with plaster.

1945: Secularization of Turkey; converted to a museum, revealing and restoring the mosaics and frescos.

2020: Remains a museum until later this month.

From the Chora museum website:

The Turkish word Kariye is derived from the ancient Greek word Chora meaning outside of the city (land). It is known that there was a chapel outside of the city before the 5th century when the city walls were erected…

Chora Church (Chora Kirke) was destroyed during the Latin invasion (1204-1261) and repaired in the reign of Andronikos II (1282-1328) …

The mosaics and frescoes in the Chora are the most beautiful examples dating from the last period of the Byzantine painting (14th century). The characteristic stylistic elements in those mosaics and frescoes are the depth, the movements and plastic values of figures and the elongation of figures.

Anastasis: the “harrowing of hell”

The Chora is the home of one of the most famous and important Byzantine icon frescos in the world, the Anastasis of Chora. This is a Byzantine prototype1 that you see copied around the Christian world in mosaics, frescos and panel icons. Christ has entered hell in triumph, thrown down its gates, literally crushing death under His feet, and grasps Adam and Eve by the wrist and hauls them bodily out of their graves. He then leads a grand procession of figures of the Old Testament out of hell.

Its complex images depict Christ’s descent into Hades2: his victory over Satan, death and darkness; his deliverance of the righteous from Hades; and his victorious resurrection on Easter morning. The Latin Church calls this event the Descent into Hell (Limbo), which represents only the first phase of the tripartite Anastasis that in the east includes the most important aspect; the raising of mankind through Christ’s resurrection.

This specific iconographic prototype, showing Christ conquering Hades and freeing the righteous from Hades, emerged sometime in the later Byzantine period. Earlier portrayals of the Resurrection existed, but they often focused on the empty earthly tomb or Christ's post-resurrection appearance to Mary Magdalene. So it is reasonable to believe that the Christian theology connecting the Anastasis, the Resurrection of Christ and His triumph over death, with the contemplative tradition of prayer dates from about this time.

The Chora Anastasis (14th century) is undeniably significant for its monumental scale, detailed narrative, and intense colours. It represents a pinnacle in the development of the Anastasis iconography, showcasing the refined artistic expressions of the Palaiologan Period (1259 to 1453).

In her book “Hesychasm3 and Art” Dr. Anita Strezova writes about the significance of this icon prototype. “expresses the central principle of Byzantine theology: the ability to acquire knowledge and experience of God through vision.”

It is a depiction primarily of the pure light of God, contrasted with the darkness of death and hell; “In him was life; and the life was the light of men. And the light shineth in darkness; and the darkness comprehended it not.”

The feast of the Transfiguration shares a common theological basis with the Anastasis, and both are a true expression of the divine nature of Christ and manifestation of the phenomenon of the supernatural light of glory. If the Transfiguration fulfills the Theophany on Mount Sinai, the Anastasis anticipates the Parousia. The Anastasis also expresses the well-known Eastern Christian doctrine of theosis4; the mysterious relationship between God and his creatures according to energy or grace. It also affirms the reality of the hypostatic union of two natures in Christ after his death and resurrection, as Christ remains perfect man and perfect God in heaven as well as on earth.

We have icons to teach us and help us to enter into the subtle depths of Christian theology, not merely to tell didactic stories. As such we have icon prototypes that are painted in a very specific way to ensure that these theological truths are conveyed as accurately as possible.

Dr. Strezova writes: “The iconography of the Anastasis was consistent until the 14th century, when the conflict between humanism and hesychasm during the Palaeologan era resulted in the establishment of new artistic trends with new motifs and subjects.”

“Although it is difficult to confirm that mystical movements were directly responsible for these iconographical changes, the fresco of the Anastasis in the Chora church illuminates the hesychast notion of theosis (union by grace).”

Thanks for reading to the bottom. I hope you enjoyed this free public post, an introduction to the great importance of The Chora monastery’s icons in the greater scheme of Christian sacred art, and why it is vital to preserve and protect them.

I would like to take a moment to thank the new paid and free subscribers who have signed up in the last few days.

In the next paid members’ post, we’re going to take a small trip to visit an Umbrian Romanesque church. Later we’ll go deeper into how we look at art, beyond being mere “idolaters” of celebrity paintings. And we’ll talk about how we can learn to integrate thoughtful looking, looking with focused attention, into daily life using drawing. I hope you’ll join us. It’s only $9/month.

We’re going to have to talk more later about the concept of “prototypes” in Christian sacred art. It’s big. Really big. Might be a whole “package” for the Byzantine section of the course.

Not quite the same thing as the hell of eternal damnation. In the Latin Catholic Church we call it “limbo”. In the east it’s called Hades and has a much more Classical Greek implication of a waiting place.

Hesychasm is the contemplative monastic tradition practiced in Eastern Christian churches. Its core aim is to achieve "hēsychia," which translates to "inner stillness" or "quietness." This state of inner peace is sought through uninterrupted prayer, primarily the Jesus Prayer.

Theosis: divinisation, union with God. The ultimate goal is to experience communion with God through a state of pure, contemplative prayer, transcending personal thoughts and entering divine light.

Terrific post. Are you implying that Hagia Sofia murals might have been destroyed after the last conversion to a Mosque? Sad to learn about Chora, and grateful to learn more about those mosaics.

I was in Constantinople this past September and made a pilgrimage to the Hagia Sophia. It’s an incredible structure, despite how it’s been treated by the Mohammedans. Very sad to see its continued profanation, but it was also encouraging to see how the cross, despite their attempts, remains in various places. We couldn’t fully grasp the Theotokos icon in the sanctuary as they’ve covered it with some cloth strips.

Our party did pray some imprecatory psalms while there, with the hope of its restoration to its rightful owners. 🙏

Relatives of mine took a guided tour of the cathedral in Cordova. Their guide mentioned that it was when visiting the same place earlier that Erdogan vowed to make the Hagia Sophia a mosque, in retaliation for Spain having turned the mosque into a cathedral. It seems his march to Islamify churches will continue unabated…