Council to Conclave: The Rise of Papal Supremacy and the Roots of the Divide

Paid reader bonus: How to make an antipope (it's harder than you think)

It’s been over 2,000 years; why does everyone still care so much about the pope?

Quite a lot of us are watching the goings on in Rome right now, all waiting for the moment when the doors of the Sistine Chapel will close behind the cardinals. Then we’ll wait with fascination, and no little dread, for what will happen next. While the faithful pray for a holy successor, many of us are bracing ourselves for more turbulence. But it’s a little surprising, isn’t it? All this attention for one man in white, and an institution that was old when Charlemagne was crowned.

And yet, here’s a fun-fact, for a good bit of early Christian history, the pope was not the central figure he is today. The papacy that we know today, as an institution, was centuries in the making, and was crafted as much by the turbulent politics of the first millennium as any theological ideas.

The image we now have of the papacy - an unbroken line of supreme rulers, each one the Vicar of Christ, the visible head of the Church on earth - is, in many ways, a modern projection, the result of many centuries of development of the papacy’s political as well as ecclesiastical role. In the early centuries of the Church, the bishop of Rome was a respected voice, yes. The pope was often used as the “court of last resort” in many disputed theological and political questions. But obeyed universally? Entrusted with command over the whole Church, with authority over kings and emperors? That’s a much later development.

Given the current state of anxiety and strife over the papacy, it seems like it would be useful to gain some historical context, to deepen our understanding of how the office was seen in the early centuries of Christianity. We’ll look at its relationship with states and emperors and how the very early cracks between east and west started.

How did we get here? Well… it’s complicated.

In today’s post for all/free subscribers, we’ll look at how we got from council to conclave, from a communion of bishops, with patriarchs, to a singular throne in Rome. I hope it will help provide some historical context to examine the long, often twisting and uneven path that led to the rise of papal supremacy in the West. And we’ll take a brief look at the deep divisions it helped provoke. Readers might be surprised at how far back the east-west division of Christianity really reaches. We’ve covered much of this before, but we can put it all together today.

And for paid subscribers, we’ve got a short bonus segment below the fold: “How to Make an Antipope (It’s Harder Than You Think).” If you’ve ever wondered how the Church ended up at times with multiple rival popes - once we had three at the same time - and who gets to decide which one is real, we’ll take a short tour through some of the most dramatic and confusing moments in papal history. It’s a bit chaotic, a bit tragic and maybe strangely reassuring to know our current situation isn’t unique.

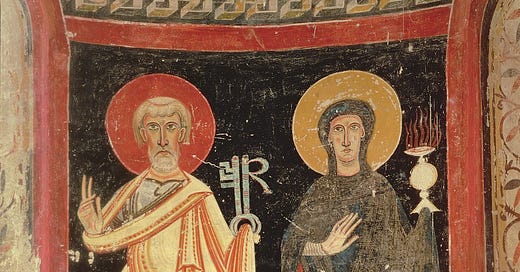

At The Sacred Images Project, we explore Christian life, thought, history, and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. This publication is entirely supported by readers — no ads, pop-ups or distractions — just thoughtful work, funded by your subscriptions.

While The Sacred Images Project has grown into my full-time work, we're now building toward an even richer, multi-layered platform, with plans for e-books, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts and more. Your support helps make this expansion possible.

If you’d like to follow along, you can subscribe for free and receive a weekly article exploring the treasures of Christian history, culture, and sacred art..

Paid subscribers ($9/month) receive a second, in-depth article each week, plus additional exclusive posts featuring in-person explorations, high-resolution downloadable images, behind-the-scenes content, and more.

If you believe in the importance of preserving and deepening our sacred patrimony, I hope you’ll consider becoming a subscriber today.

From the shop: I’m happy to offer this drawing of the Crucified Christ, “Christus Patiens” that I did in the style of the 14th century Umbrian panel crucifixes. It’s printed on the same museum quality 100% cotton, acid-free paper I drew it on.

You can browse the shop here:

If you’d prefer to set up a monthly contribution in an amount of your choice, you can also do that at the studio blog, or make a one-off donation to help keep this work going. If you subscribe through my personal page, I’ll add you as a complimentary subscriber here. And thank you.

Popes and Emperors

A lot of people look at the papacy alone, as an isolated historical edifice. This is probably because we all live now in more or less (ostensibly) independent liberal nation-states, and we can’t easily grasp the concept of Empire, let alone the way Imperium was once meshed together with the Church as a unified ruling body. Separation of Church and state wasn’t even a glimmer of an idea in the 8th century.

In the first millennium of Christian history, the pope was not the head of an independent religious organisation as we think of the “Roman Catholic Church” today. He was a bishop and a patriarch within the Roman Empire, in its eastern Christian form, and was subject to the secular authority of the emperor. Yes, he held special honour due to Rome’s apostolic legacy, but that honour didn’t mean autonomy, still less “supremacy”. The pope’s election had to be confirmed by the emperor’s representative in Italy, the Exarch of Ravenna.

In the early centuries of the Church, under the laws of Justinian I (r. 527–565), authority was shared among five major patriarchates: Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem, a structure known as the Pentarchy. Rome held the first place of honour, due to its size, association with Saints Peter and Paul and its status as the old imperial capital, but it was not seen as a supreme ruler over the others, and was not considered an independent power.

Each patriarch had jurisdiction over a major region of the Christian world and was responsible for safeguarding doctrine, maintaining order, and participating in ecumenical councils. While the bishop of Rome was often appealed to in cases of dispute, the early Church operated on a model of collegiality, not centralised command. Councils, in conjunction with the papacy - but not popes alone - were the ultimate authority in resolving theological crises.

Read more about the last moments of the united Christian empire here:

How Islam broke Christendom: the papacy under siege

That balance changed dramatically after the rapid Islamic conquests of the 7th century. Between 637 and 642, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem all fell under Muslim control. Though the patriarchates continued in diminished form, their influence was severely curtailed and their ability to function as independent centres of Christian life effectively collapsed. Constantinople remained, but became increasingly embroiled in its own political and theological struggles.

This left the bishop of Rome as the only patriarch in the Christian world with real independence and institutional continuity. Cut off from the East and increasingly isolated in a disintegrating western empire, the pope began to assume a more assertive role, still as a spiritual leader, and now also as a political figure, laying the groundwork for a radically new understanding of the papacy’s place in the Church.

In the early 8th century, the papacy was in a precarious and transitional position. Under the authority of the Byzantine emperor, the pope was expected to operate within the imperial system and cooperating with Constantinople. But in practice, imperial influence in Italy was weakening fast. The Exarchate was under pressure from the advancing Lombards, the empire itself was distracted by wars on its eastern frontiers, and theological tensions - especially over the various heresies like Monothelitism and, soon after, Iconoclasm - were straining the bond between Rome and the emperor.

The pope was increasingly left to govern and defend Rome on his own, navigating between hostile Lombard kings and distant, encroaching Muslim armies and raiders from the sea, and unreliable and distracted Byzantine rulers. This growing isolation, combined with doctrinal conflict, set the stage for a dramatic shift in alliances and in the self-understanding of the Roman Church.

The heresy that broke an empire

What pushed things toward open fracture was the sudden eruption of Iconoclasm under Emperor Leo III in 726. When Leo began issuing edicts against the use of sacred images, Pope Gregory II refused to comply. He condemned the emperor’s interference in theological matters and rejected the imperial decrees outright.

Read more about the pope’s refusal of iconoclasm here:

As we’ve discussed, Iconoclasm was more than a theological spat over icons. By the time it was all over, it had caused a major shift in political allegiance in the western, European, half of the empire. The Byzantine emperor no longer looked like a protector of orthodoxy, and worse, he could no longer protect Rome militarily. The old structures were still in place “on paper” but the spiritual and political centre of gravity was shifting. The pope was beginning to act on his own out of sheer necessity.

This would eventually lead to the decisive break, when the pope turned definitively away from Constantinople and crowned a new emperor in the West: Charlemagne. But even before that dramatic moment, the papacy was already learning to walk on its own, and choosing new allies.

The fall final fall of Byzantium in Italy: the end of the Exarchate of Ravenna

The Exarchate of Ravenna had been the main base of Byzantine power in Italy since the late 6th century. The Exarch, based in Ravenna, was the emperor’s representative in the West, functioning as both military governor and civil administrator, and (crucially) as the final authority over the pope’s election and actions.

But by the mid-8th century, Byzantine power in Italy was in sharp decline. The empire was embroiled in constant warfare on its eastern borders (especially with Arab armies), and the iconoclast controversy had alienated the pope and much of the Italian population. Meanwhile, the Lombards, a Germanic people who had been steadily expanding their control of northern and central Italy since their arrival in 568, had grown stronger and more aggressive.

More details about the fall of Byzantine Italy here:

In 751, the Lombards captured Ravenna, ending the Exarchate. The Byzantine governor was ousted, and the last official imperial outpost in the West was lost. For the first time since Caesar Augustus, there was no imperial authority left in Italy.

This was a moment of deep crisis for the papacy. With the exarch gone, the pope was functionally without a protector, surrounded by Lombard forces and unable to rely on military aid from Constantinople. The Byzantine emperor still claimed sovereignty, but could no longer enforce it. The pope had to act independently or risk being overrun.

This is what led Pope Stephen II to do something unprecedented: look north beyond the Alps in 754 to seek help from King Pepin of the Franks, bypassing the emperor entirely. That appeal changed everything, and ultimately led to the crowning of Charlemagne in 800 - creating what could be called a political schism that preceded the ecclesiastical version.

Explore our early discussion about Charlemagne and his Carolingian Renaissance here:

So what does the Church actually claim about the papacy, at the doctrinal level?

Successor of Peter

The pope is the successor of St. Peter, whom Christ appointed as the visible foundation of the Church (Matthew 16:18). As bishop of Rome, where Peter was martyred, he inherits this unique role, not as Christ’s replacement, butHis vicar and a visible sign of unity.

Supreme and Universal Jurisdiction

The pope’s authority is not just honorary. It is real, immediate, and extends to the whole Church. This was clearly defined at the First Vatican Council (1870): he holds “full and supreme power of jurisdiction” in both doctrine and governance.Infallibility (as defined, restricted, not unlimited)

The pope is not personally infallible. Infallibility only applies when he solemnly defines a doctrine of faith or morals ex cathedra, intending to bind the entire Church. This has been used very rarely (e.g., the Immaculate Conception and the Assumption).Servant of the Servants of God

The pope’s office is one of service, not domination. The title “servus servorum Dei,” coined by Gregory the Great, remains the ideal: the pope is meant to be a humble guardian of the faith, not an imperial ruler.

From the forged Donation of Constantine to the real thing under Charlemagne

The so-called “Donation of Constantine” was a forged document, probably composed in the mid-8th century in Rome, that claimed Emperor Constantine had granted the pope sovereignty over Rome, the Western Empire, and various imperial symbols of power. According to the text, Constantine, out of gratitude for being healed of leprosy and converted by Pope Sylvester I, gave the pope the imperial palace, the city of Rome, and authority over “all the provinces, places and cities of Italy and the western regions.” Though a pious fiction, the document expressed what was becoming an increasingly real and strategic aspiration: that the pope held spiritual authority and also temporal sovereignty derived from the earliest Christian emperor.

This forgery mattered precisely because it was motivated by the fact that the actual emperor (the one in Constantinople) was distant, unreliable, and, by the pope’s standards, doctrinally compromised, thanks to iconoclasm. With Constantinople failing to defend Rome or uphold orthodoxy, the Donation provided ideological cover for the pope to assume temporal authority in central Italy that was later formalised by King Pepin’s real donation.

It also laid the conceptual groundwork for what happened on Christmas Day, 800, when Pope Leo III crowned Charlemagne as “Emperor of the Romans.” That moment wasn’t just about power, it was a theological and historical claim: that the pope, not the emperor, was now the one who could confer legitimacy, and not the other way around. The Donation of Constantine gave that claim an imagined precedent rooted in antiquity. It may have been fiction, but it helped to create a new political-religious reality.

A new kind of authority: popes crowning emperors

What happened on Christmas Day, 800, was not just a political stunt; it was a radical reimagining of both imperial power and papal authority. Until that moment, neither popes nor patriarchs had claimed the right to create emperors. The emperor gained cosmic legitimacy, being seen as God’s anointed ruler, rather than being legitimised through military victory, lineage or election. This reframed the new western empire as essentially a divine institution, a part of God’s sovereign plan for mankind.

By crowning Charlemagne, Pope Leo III reversed the traditional hierarchy of powers. For centuries, emperors had installed, confirmed and often dominated popes. The coronation of Charlemagne symbolised a new idea: that the Church, not the Empire, was now the source of political legitimacy. The pope wasn’t just the bishop of Rome anymore. He was the spiritual authority above kings, with the power to bestow or withhold imperial dignity.

This moment planted the seed for centuries of papal claims to authority over secular rulers. Later popes, especially during the Gregorian Reform movement, would build on this precedent, asserting the right to depose kings, arbitrate imperial elections, and intervene in state affairs. None of the ancient patriarchs of the East had ever made such a claim.

So why does everyone still care about the pope?

So, we come back to our original question above: it’s been over 2,000 years since the office was established; why does everyone still care so much about the pope? We can see now that the answer lies not just in theology. We can see that the papacy’s underwent a radical transformation in the 8th century. Cut off from the East, abandoned by the empire, and forced to act independently, the papacy was essentially compelled to redefine itself, no longer only as a bishopric or patriarchate. Now he was empowered as a sovereign spiritual and political authority.

Neither the gravely weakened, theologically divided, and effectively besieged Byzantine emperor, nor the ancient patriarchs, had the power to address this radical change. The structures of the old Christian world, rooted in conciliar governance and imperial oversight, were collapsing.

In his alliance with the Franks, the pope became a kingmaker as well as a protector of doctrine, and crucially the one who could crown an emperor. That shift, unthinkable in all the previous centuries of Christianity, laid the foundation for everything that came after: the rise of the papal monarchy, the centralisation of the Western Church.

What emerged by the end of the 8th century was a new western empire, founded on the authority of a papacy fundamentally politically reimagined, centralised as the axis of authority in the West. What happened next was the establishment and growth of Europe as a Christian empire, that has lasted in one form or another into our own time. Historians still call what we live in “western civilisation” because of what happened that Christmas day in 800.

And that’s why, twelve hundred and 25 years later, all eyes are on Rome during a conclave. The Church and the papacy were reshaped in a moment of profound crisis, and never looked back.

We’ll talk more later about whether that was a good thing.

I hope you’ll consider subscribing to join us below for our bonus section for paid subscribers below the fold, where we’ll talk about what an “antipope” really is and how you go about making one. It’s harder than you think.