Deep Looking, drawing and the road to true prayer

How learning to draw what I saw taught me to pay more attention to God

Here’s a little re-edit and expansion on a couple of posts I wrote on the studio blog some time ago about how I’ve found doing art, drawing iconographically, painting icons and thinking a lot about Christian sacred art, has helped my spiritual life. I wrote these while I was living alone after losing my home to the 2016 Norcia earthquakes and suffering quite a bit from feeling isolated and lost. In the end, through the practice of sacred art and liturgical, monastic style prayer, I found myself pointed back in the right direction.

I’ve fallen off the Divine Office wagon lately - as one does - and it’s starting to seem like time to climb back on.

What exactly is the “pursuit of holiness”?

How do you get to holiness? How do you get from being an ordinary person, full of flaws and the vile residue of sin, to the heights of sanctification, theosis, divination? I think it has to do with something I call “deep looking,” a method of seeing divine reality that can be learned.

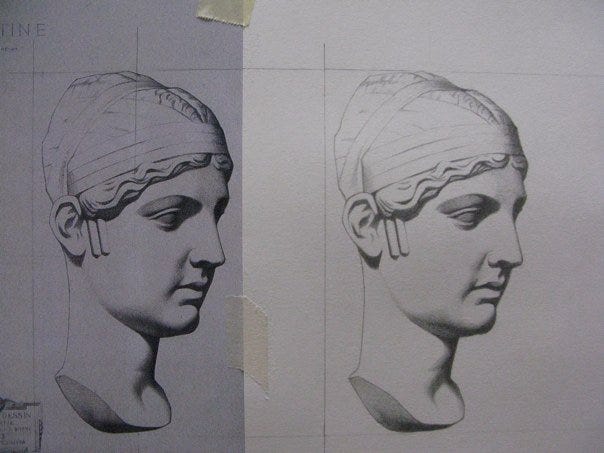

I was surprised when I started my drawing classes back in 2009 that I was perceiving something that I had never suspected existed before; a kind of world of acute observation, sharpened perception, that was like a different reality, a different kind of world. It was something I struggled to put into words, but I knew I was being changed in a deep way by this training. And it gave me a hint that there were whole worlds that could be perceived if we are taught correctly how to perceive it.

Deep Looking; a way of perceiving hidden reality

A few years ago a well known drawing instructor, author and painter, Juliette Aristides, gave a lecture on the connection between the transcendental, Beauty, and our search for meaning in life.

Juliette Aristides, is a leading light in the Atelier movement, working out of the Seattle studio she founded. She teaches the same programme of classical realist academic drawing that I was able to receive in Rome, part of a now-global movement to return to rigorous professional training for painting and sculpture that nearly died out in the 20th century. (I wrote about it here.)

She asks why modern people have such difficulty seeing beauty, or why they think it is an entirely subjective matter; beauty is a kind of mental illusion created by the perceiver and imposed on an otherwise meaningless and chaotic world. “There’s a very big difference between seeing and observing,” she said.

This green button will take you to my studio blog, Hilary White; Sacred Art, where you can see a gallery showing my progress learning how to paint in the traditional Byzantine and Italian Gothic styles. It includes a link to my PayPal where you can make a donation or set up a monthly support to become a patron. Many thanks to those who have already contributed. At the moment, patronages, one-off donations and occasional sales of paintings are my sole source of income. If you’ve enjoyed this site, I hope you’ll consider donating so I can keep doing it.

And that’s the key to how to find both beauty and meaning; learning, consciously, to see, with clarity, attention and open perception. And that’s what the classical training in drawing does; it alters your ability to perceive and grasp the information brought in by your eyes. It hones and sharpens your ability to perceive. And it does it by teaching what Aristides calls “deep looking,” that is, looking with the mind and not just the eyes. This deep looking, she says, is a form of meditation that helps the looker connect with reality in a more profound way.

“Why drawing? The interesting thing about drawing is it's like writing poetry, it's like meditation, it's like deep listening. It helps us think, it helps us slow down, helps us connect to the life that is ours.”

She is not a Catholic, but her point about drawing being "deep looking" is connected in a way she might not have realised with a concept in prayer; that prayer, properly speaking, is looking. And "deep looking" is a good way of describing it.

We moderns aren’t taught anything about drawing, and even less about prayer. If we think about it at all, we think of it as talking. Prayer for most people is just asking God for things. But the old Church Fathers say it’s quite a bit more than that; it’s a kind of alteration of perceptions through long exposure, deep looking.

Drawing in the classical or academic way is really an exercise in training the eye to see accurately. This comes from training in looking, and learning - through a long and sometimes painful process - to discard all that is false, everything, every phantasm that our brain generates to explain or interpret what the eye plainly sees. The process of learning to draw is a mental discipline in learning to see and accept Things As They Are - the Real.

We are not aware of this most of the time, but our ability to perceive is often not well developed. How many times have we said, “Oh, I was looking straight at it but didn’t see it.” You’re lost in thought, not paying attention, so you don’t “see” what you’re looking at. Do you think you could draw a portrait of the face of your mother or spouse - a face you know better than your own - just from memory right now? Probably not.

We don't really remember this in our culture, but seeing accurately - really perceiving - is something you have to learn. And once it’s developed by teaching, the ability to see accurately very quickly gets applied to other areas of information processing. Learning to mentally strip away all the things our minds generate to explain reality teaches us in every way to be more careful and objective observers of life. This is why it used to be considered a necessary part of every child's education.

It's slow. I studied for four years, part time. And as soon as I started I knew I had found something extraordinary; a kind of doorway to a different kind of world. The training changed my brain, permanently. People tell me all the time, “Oh, I can’t draw,” as if it is some magical ability. But in fact they can; they just have to be taught properly. When I started I couldn’t draw, and I've got an ability now that I simply didn't have when I started the training and it's still one that I can turn on and off at will. I've written about this elsewhere so I won't labour it, but this kind of change, the alteration at a deep level of my ability to perceive reality, can't be had without doing this labour of deep looking.

What does "pray without ceasing" mean, and if it's necessary for the pursuit of holiness, how do we do it?

And this is a hint of what pursuit of holiness entails. You can't do it over night. That's why it takes years and years of steady, constant exposure, the removal of all obstacles (which is what distractions and entertainment really are), the purging of faults, and the slow, regular recitation of the Word of God in the Psalms. It has to seep into you so that in the end, the radiance of God permeates your whole self. You, in effect, become the thing you pursue, which is why in the East the process of sanctification is called "divinisation".

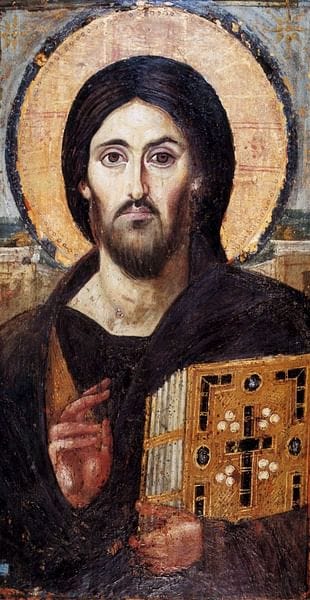

As this Orthodox monk, Fr. Seraphim Aldea, the founder a monastery on the Isle of Mull in the Hebrides said, the core of true prayer is that you sit and look at God, and He looks back at you. This deep looking kind of prayer is what changes you. The tremendous, indescribable power of God cannot help but change you if you allow yourself to be exposed to it.

The Benedictines use a combination of sung prayer, the Divine Office, normally with the meditative cadences of Gregorian Chant, and Lectio Divina, the slow meditative reading of Scripture.

How is it possible to acquire this constant state of prayer? Well, the Desert Fathers recommended the Psalms, which is the meat and potatoes of monastic prayer - or as Br. Ignatius told me once, the Psalms are the meat of the sandwich of the Divine Office. He was referring to those times when you might have to skip out early to do some important work, "Make sure you stick around for the Psalms. That's the part that will feed you."

Chanting the Psalms many times throughout the day is the “deep looking” done by monastics. It helps them to infuse, in a sense, into your thinking during the times of the day when you're not chanting the Psalms - when you’re working. It's a little like having a song stuck in your head that you find yourself humming throughout the day. A deep familiarity, an infusion, with the Psalms that can be gained through chanting them, can radiate their ideas into your own mind. This is the way that your own thoughts can be calmed and quieted and turned into the thought of God.

This is a means of giving you what the Fathers called “the memory of God," a constant "state" of being at prayer. It is a way of replacing the agitated yammering that is the normal condition of mind for many of us, with a sublime condition of constant attention to God and His reality. To live constantly in the presence and awareness of God.

"Flee forgetfulness" to receive the "memory of God" and, as St. Basil says, you will receive "the holy thought of God, stamped into our soul like an in a radical seal, the stamp, by means of a distinct and continual remembrance." St. Basil says it is possible to maintain this condition of remembrance in all circumstances, even during physical labour.

A seal, or stamp, of the "holy thought of God" in your soul. You will, in other words, be changed forever by looking at God all the time.

This is beautiful. Thank you

Excellent post. Thank you!