Who saved Art, and why?

Following is Part II of the pair of articles I wrote for the Remnant back in 2016, the second half of the question, just what the heck happened to art? We asked the question last time, in “Who killed art, and why?” and now we’re going to talk about how it was rescued, astonishingly, by one man.

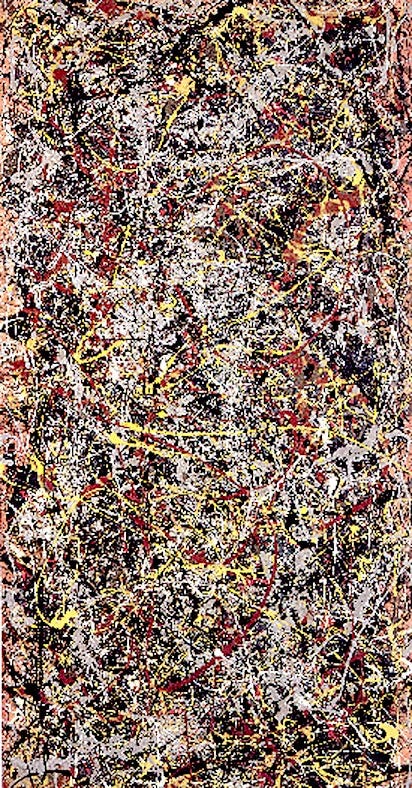

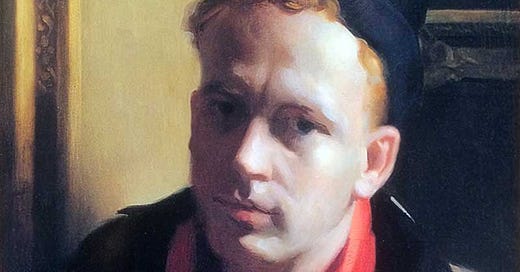

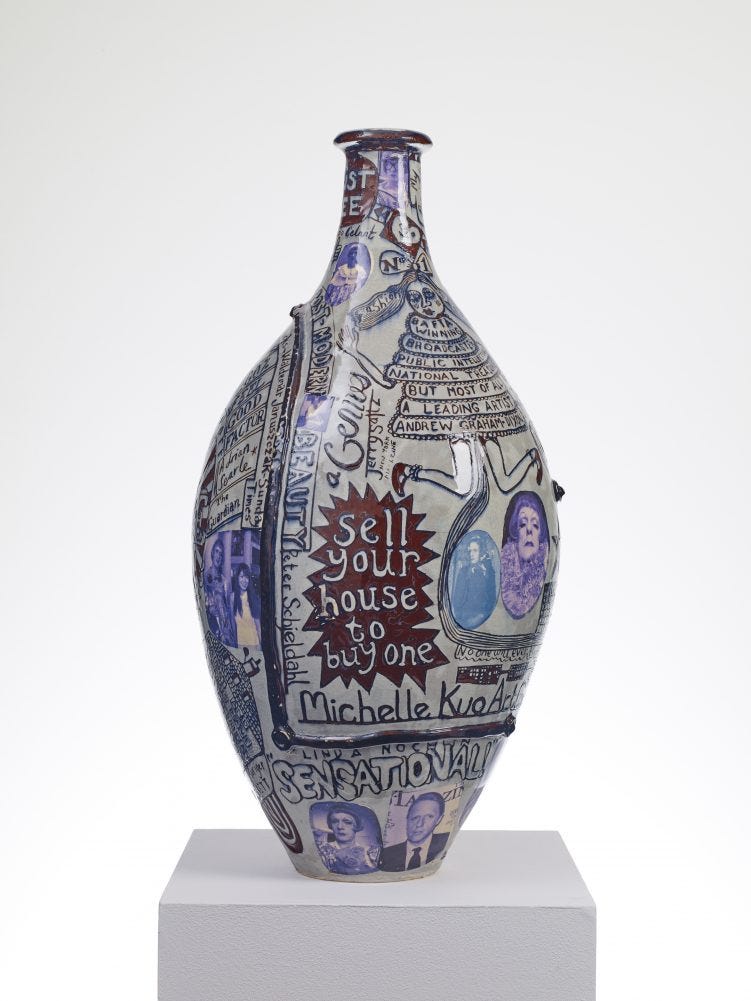

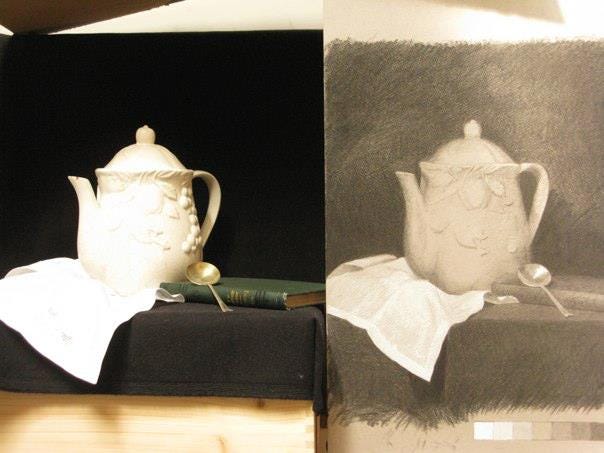

We all know what I’m talking about. How did “great art” go from this:

To this…

“How did ‘art’ deteriorate so abruptly, starting in the early 20th century, from human work channelled through highly developed craft and technical skill to depict a sublime, orderly and beautiful universe to a bizarre, nihilistic celebration of ugliness and anti-rationality?”

“In one sense it was quite abrupt. In 1917, an artist and ideological change agent named Marcel Duchamp placed a porcelain urinal on a pedestal in an exhibition in New York, scrawled the word “fountain” on it and signed it “R. Mutt.” …

“Dadaism” is part of the movement connected to those early political philosophies of revolution that brought the world in the 20th century on a path through mechanised total war, industrialised mass-murder and has finally left us today all standing together, half-mad, on the brink of nuclear annihilation.

The man who saved Art

by Hilary White

for The Remnant, 18 February, 2016

(edited & revised)

The man in the pretty purple frock

In 2003, upon accepting Britain’s most prestigious contemporary arts prize, the ceramics artist Grayson Perry took this moment in the national limelight to chastise the arts establishment for their tardiness in recognising the merit of the work of “transvestite potters” everywhere. The 42 year-old potter accepted the £40,000 Turner Prize dressed as a little girl in a £2500 lavender flower print frock.

He said at the ceremony, to which he was accompanied by his wife Phillipa (a psychotherapist) and daughter Florence, “I think the art world had more trouble coming to terms with me being a potter than my choice of frocks.”1

Poor chap. Obviously a victim of the art establishment’s vindictive stodginess. No doubt to make it up to him, in 2013 he was appointed chancellor of University of the Arts in London and made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in the 2013 Birthday Honours for “services to contemporary art”.

Perry’s works are known for combining classical forms of pottery with photo transfers of scenes of sadomasochistic sex, and themes of emotional child abuse and neglect that he says were reflections of his upbringing by an abusive stepfather and emotionally distant mother. Perry has stated that he uses the medium of pottery to convey his pictorial themes because of its inherent “innocence” and “humility.”

His work is consciously subversive and ideological. He has said, “I want to make something that lives with the eye as a beautiful piece of art, but on closer inspection, a polemic or an ideology will come out of it.”

Recap: How did we get here?

Just under a hundred years later, Grayson Perry is only one figure in a vast and apparently never-exhausted parade of artists eager to carry the Dadaist torch – while raking in the huge financial rewards we now offer the culturally transgressive – into the indefinite future.

Duchamp’s anti-art, described as “the sickest, most paralyzing and most destructive thing that has ever originated from the brain of man,” was intended to shock, to outrage and to offend artistic sensibilities in the public, and finally to completely overturn traditional artistic standards, education and goals among artists and art promoters.

The occasionally cross-dressing and frequently scatological Marcel Duchamp would certainly have recognised in Mr. Perry a kindred spirit and ideological fellow traveller. Duchamp’s nihilist anti-rational political protest movement in art and poetry, had arrived in North America only a few years after it had begun to take root in Europe. Its purpose, according to the stated goals of its leftist-anarchist founders in Zurich during World War I, being to shock, to outrage and to offend artistic sensibilities in the public, and finally to completely overturn traditional artistic standards, education and goals among artists and art promoters.

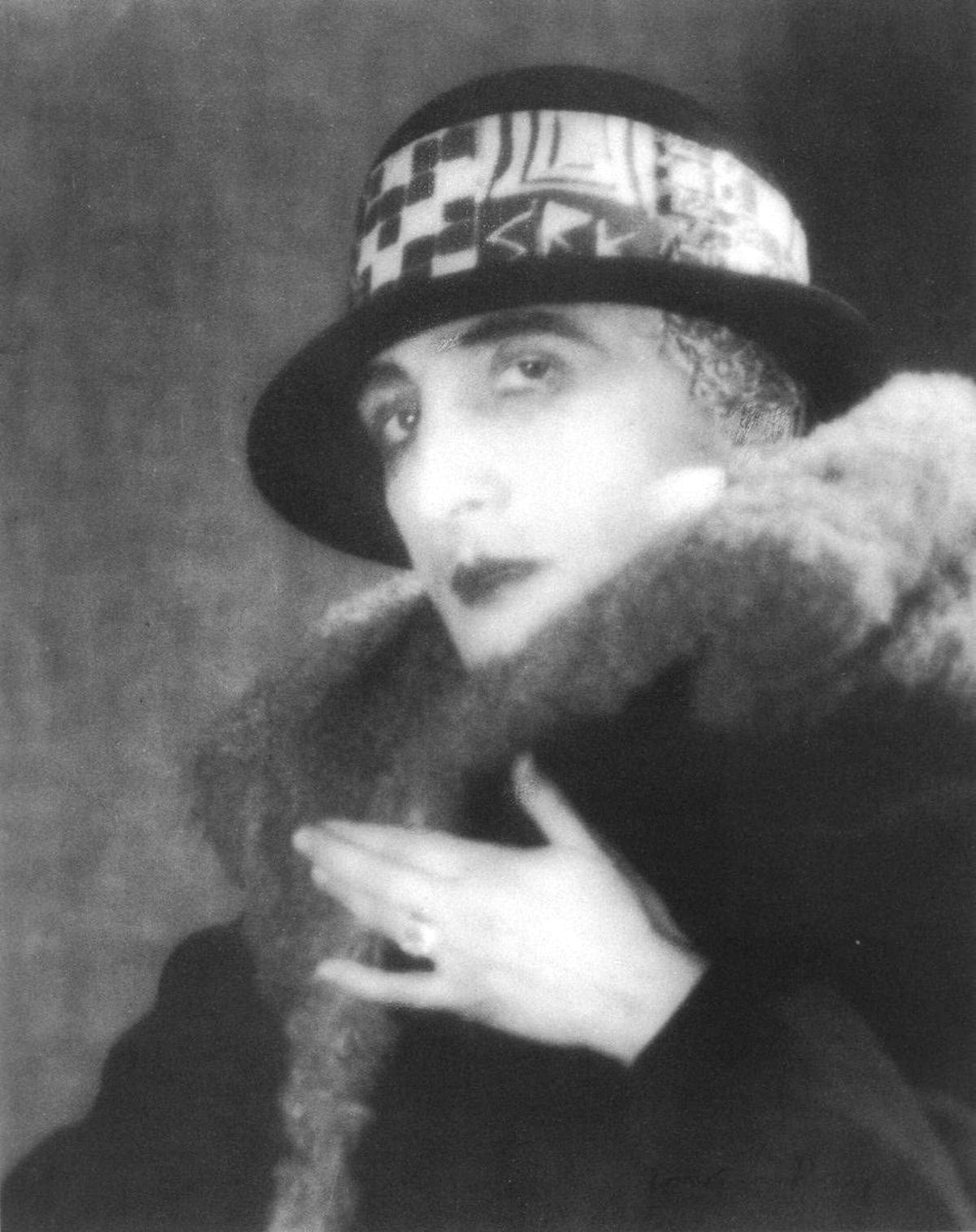

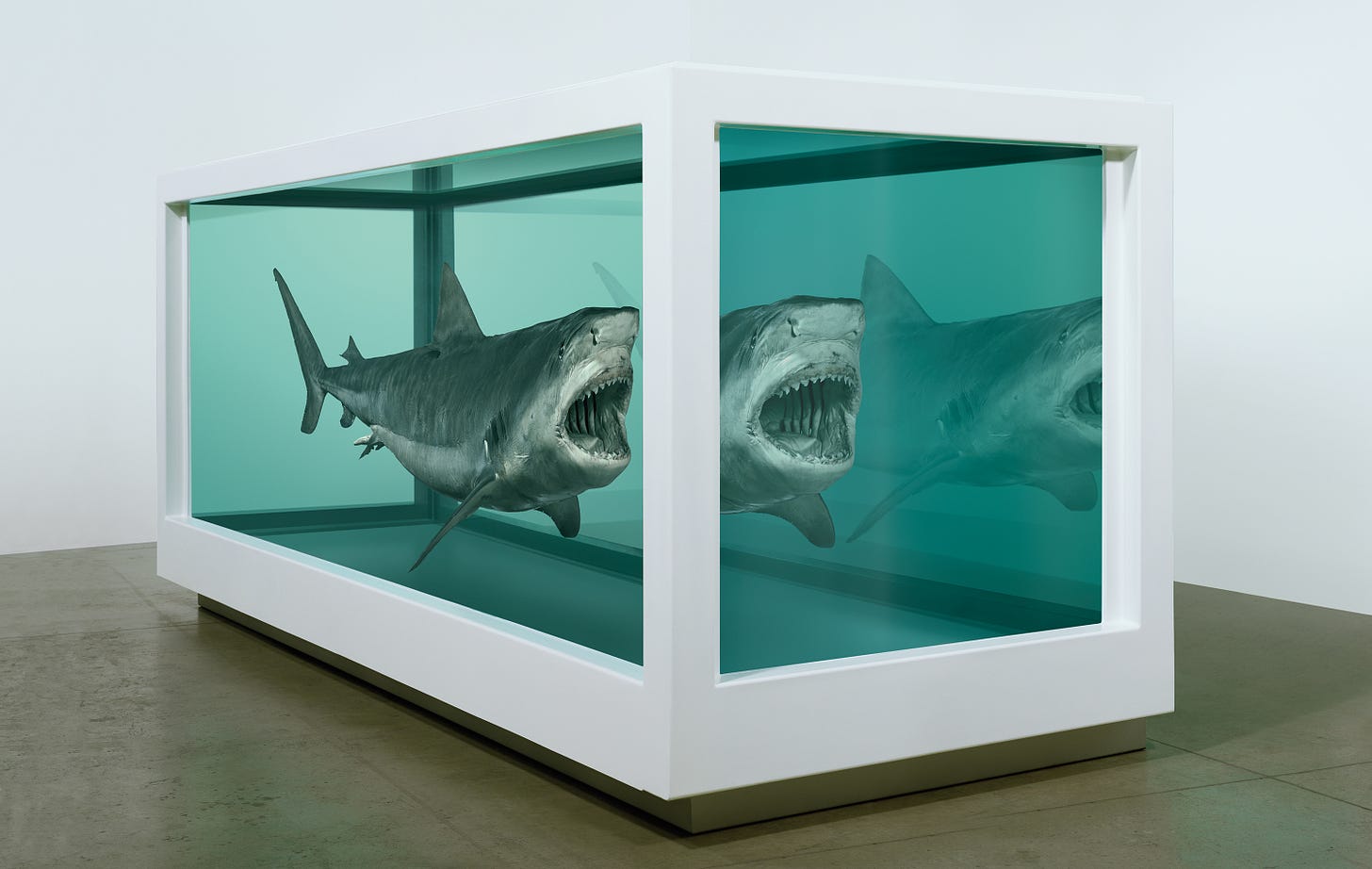

The Turner Prize is perhaps a good metric by which to judge the durability of the Dadaists’ anti-values. Its recent recipients have included Damien Hirst for his “conceptual” work of a dead shark suspended in formaldehyde, and a dirty unmade bed by Tracey Emin, who once bragged in an interview that some of her favourites among her own works were executed while she was blind drunk.

Emin in 2011 took her place of honour as Professor of Drawing at the Royal Academy of Arts; one of the first female professors since the Academy was founded in 1768.

Richard Lack to the rescue: the atelier movement born

“Few living painters who could execute a figure composition [that] would stand favourable comparison with even a second-rank nineteenth-century work…The instructor substitutes flattery for method and gives the student little or no direction. The tiresome dictum that a student’s creativity should not be frustrated by interference from the instructor is usually introduced at this stage.”

As all modernist social revolutionaries know, the key to everything is to get control of the educational institutions. Ensure that not only will the revolutionary concepts be taught in perpetuity, but that counterrevolutionaries will be forever barred from active leadership roles.

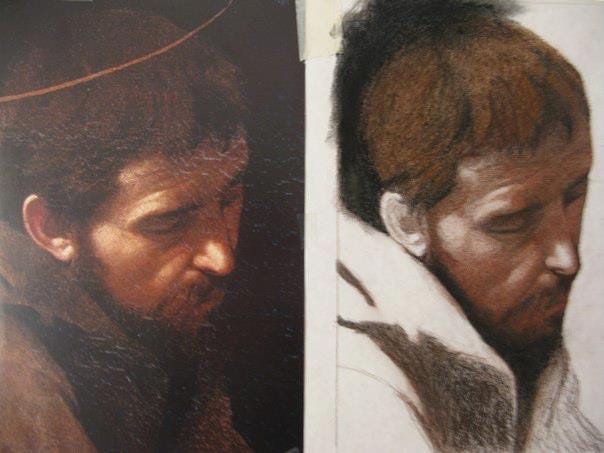

By the 1960s, even while students who dared to express a love for Renaissance masters or a wish to learn accurate observational drawing techniques were being systematically weeded out of art schools, a small group of artists and students were pushing back against this now-industrialized cult of ugliness. A whisper was growing in the crowd, that in the following decades would grow to a roar; “The emperor has no clothes!”

In 1969, an obscure American painter published an essay titled, “On the Training of Painters,” that was perhaps the first time anyone had shown the wherewithal to stand up in the face of the radicals and call them naked shysters2.

Richard Lack, who had been among the last surviving recipients of the ancient system of one-to-one training in classical, academic drawing and painting techniques, wrote that in the world today, there are “few living painters who could execute a figure composition [that] would stand favourable comparison with even a second-rank nineteenth-century work.”

Lack continues:

“Perhaps the only time any strong influence is exerted is when the instructor discourages the student from ‘copying nature’ and working in a ‘realistic’ manner. A student who is foolish enough to persist in these illicit pursuits is gently, and sometimes not so gently, ridiculed to the point where he soon gives up his hapless aims. To stick to his guns under circumstances such as these, he must indeed be a strong personality.”

“Today the older tradition of picture-making is practiced by only a small minority of painters, most of whom are forced to work . . . outside the Art Establishment. If proper training were available to young students, there would be many more.”

History was to prove him prescient.

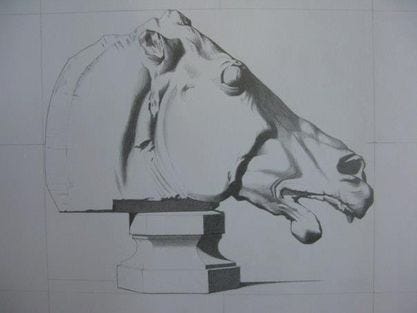

Starting over: the classical realist tradition rescued

The same year he founded the Atelier Lack, a small, non-profit school of drawing and painting in Minneapolis with an apprentice program based on the teaching methods of the 19th-century French ateliers and the Boston impressionists.

Art instruction in universities and mainstream, accredited (ie: government-sponsored) art schools was, and for the most part remains, a disaster with the modernists and their politically motivated ideologies still very firmly in control. Art students who express interest in classical techniques are either shamed and browbeaten into silence or simply kicked out. Invariably, none of them is ever taught to draw.

It has become the common complaint of those who graduate from mainstream institutions, that the main reason the skills are not taught is that the instructors themselves do not possess them. Along with penmanship, Latin and Greek, basic instruction in how to competently render a scene or figure in pencil, a skill that was once a normal part of the schooling of nearly all children, is nowadays looked upon as a kind of magic trick, possible only to those lucky enough to have the magical Harry Potter drawing gene.

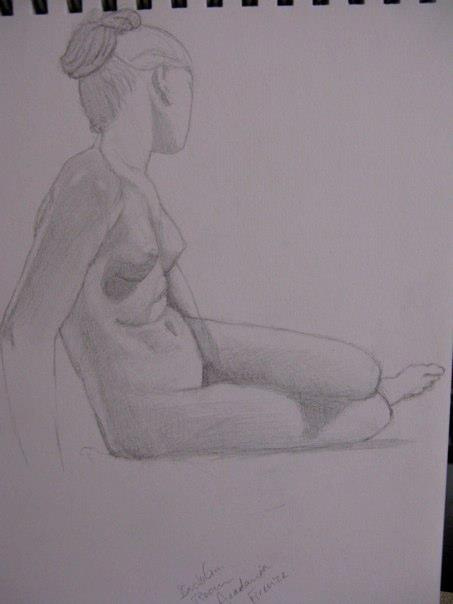

But this assumption has been produced by the nearly universal loss of competent and systematic art instruction. In fact, Juliette Aristides, a Classical Realist painter and instructor who founded the Gage Academy in Seattle, wrote in the introduction to her textbook, “Lessons in Classical Drawing,” that competence in drawing and painting is a skill like any other. “Drawing is as teachable as math, music or writing…The most important thing a student can do is get time-tested information and build on it consecutively, allowing plenty of time for practice.”

In her own study, she says, “I understood first hand that studying art is a lifetime pursuit, endlessly challenging and rewarding. I also learned that drawing is as teachable as math, music or writing. Anyone can draw… The most important thing a student can do is get time-tested information and build on it consecutively, allowing plenty of time for practice.”

Lack was working from a tradition that could be reliably traced back at least to the time of the Italian Renaissance. His instructor in the 1950s had been Boston artist R. H. Ives Gammell (1893–1981) who had studied under William McGregor Paxton (1869–1941) who had studied with 19th-century French artist, Jean-Leon Gerome (1824–1904). This type of instruction had produced some of the greatest figures of western art, names like Leonardo, Raphael and Michelangelo Buonarroti, who had all apprenticed at an early age in what was then understood to be the blue-collar trade of painting.

He opened his school in Minneapolis and began the work of rescuing art from the grip of the modernists, one student at a time. What was taught at the Atelier Lack was the same rigorous technical drawing and painting skills that had for so long been actively suppressed in mainstream programmes. While university art departments continued to emphasize the values of Anti-art, Lack set about training a new generation in the ancient tradition of exacting and painstaking one-to-one instruction in accurate rendering of subjects from life.

The movement goes home: the internet and the revival of art in Europe

In 1985, Lack founded the periodical, Classical Realism Quarterly and in 1988 the American Society of Classical Realism was organized to promote the values of the movement. By this time, Lack had trained a significant group of young realist artists, and the movement had gained ground as the graduates moved around the world founding ateliers of their own.

Today the Classical Realist revival is stronger than ever in the US and has spread to Canada and is finally starting to grow in Europe, particularly with the founding – by two of Lack’s former students – of the Florence Academy of Art in Florence, Italy. The Florence Academy has brought the old/new tradition back to Europe and its graduates have opened schools in Norway, in Barcelona, Madrid, Stockholm, Rome, London and Edinburgh.

Since the advent of the internet, it has become easier than ever to find schools and even to do the full course of study online. [Update 2022] Since the Covid era, many instructors - whose livelihood was threatened by lockdowns and cancellations of whole years of classes - turned to the internet to offer instruction on the new platforms like Patreon, Skillshare and Udemy.

Modernism’s future: none

Dr. Gregory Hedberg, a lecturer and art historian who had watched the collapse of traditional art instruction with growing unease, discovered the Classical and Contemporary Realist revival and ended up as the first director of the New York Academy of Art, a leading school in the movement.

Hedberg writes of another aspect of the revival movement; the failure of the modernists to interest younger artists. Hedberg writes of a recent survey of working artists in the US, among whom “older artists seem almost inevitably to include shock, angst, or politics in their works - an impulse to disturb…”

“On the other hand, a growing majority of American artists who today are under 40 years old seem more intent on creating paintings that are visually beautiful, rather than emotionally disturbing.

“Rather than needing time to mature and ‘develop an edge,’ these young artists are in fact very conscious of what they are doing.”

But the ateliers are expanding, getting new and larger facilities and founding new campuses. Young art students are flooding into classes and the addition of the internet has only accelerated the growth.

I took classes at a small private realist atelier in Rome between 2009 and 2013. It was an exercise in re-learning how to see and observe with painstaking accuracy.

I studied in that little studio – she has since moved to larger and even more beautiful quarters in a historic artists’ section of Rome – for four years.

I struggled and fought and cried and, as all art students do at some point, even stomped out in a frustrated rage once or twice.

And in the end, it changed my brain forever. My ability to perceive reality has become more acute, perception of the physical world has changed in a way that is almost impossible to describe. I carried on with classes and practice at home all while working a full time job and even during cancer treatments. There’s nothing like concentrated mental-but-non-verbal work in a formal class setting to calm and focus the mind, and to teach one the difference between reality and our fears.

Thanks for reading to the end. I keep saying I hope to be more regular with these posts, and it remains a goal. But writing is infrequent because it is slow; a whole working day that is not spent painting to do a piece like this with lots of background reading and image searching and organising of thoughts. If you would like to see some of my “real” work, my painting, you can click on my Ko-Fi page, Hilary White; Sacred Art, here, where you can also drop a few coins in the tip jar if you enjoyed this. You can also follow me at Hilary White: Sacred Art on Facebook and you can see a little hint of the Old Hilary White being cranky on Twitter too. Many thanks to all who have contributed to make it possible to keep working - the “struggling artist” thing doesn’t last forever, but it is a struggle for a while. And welcome to all who have recently joined in the conversation here at my Substack. Stay tuned.

I wouldn’t waste too much energy on outrage. Most of these kinds of shenanigans in the art world are really a form of marketing that turns a mediocre potter into a world-renowned “artist,” mostly by selling the schtick. The actual pots are more or less beside the point. It’s mostly done, quite literally, for attention, in the same way rock musicians of the 1970s wore stage makeup and outlandish costumes to sell otherwise-uninteresting music.

When I wrote this piece for the Remnant in 2016, I didn’t know that Pietro Annigoni had got ahead of Lack, with his manifesto against the Modernists and avante garde, by more than 20 years in Italy.

Miss White-

This gives me hope. Thank you. For some reason, music was able to hold out longer. When I went to music school in the late Eighties, the curriculum was centered on Bach. This wasn't a restoration but a continuation. I have no idea the state of things now.

I do have to wonder whether this same old/new restoration and renovation is happening in other areas. I hope so. But that classical painting schools are growing is very good news.

I hope you are well. -Jack