Who killed art and why?

Dadaism: "the sickest, most paralyzing and most destructive thing that has ever originated from the brain of man"

Everyone seems to have enjoyed reading in our post the other day about Pietro Annigoni and his “Manifesto of Painters of Reality”. I think it strikes a chord with people who are effectively being gaslighted by elites: “You aren’t clever enough to understand why you have to like our rubbish art, peasant!”

To this bullying, we say, “No, actually you are as equipped as anyone to know rubbish when you see it and you get to call it that.” The emperor is not only stark-nekkid, he’s a raving loon.

I’m not the biggest fan of Annigoni’s painting but I have a huge appreciation for his courage and determination to give two fingers up to those shysters and to keep doing what he was doing.

Painting reality, he said, was to be a “moral” exercise that “should be filled with the same faith in man and his destiny, that had made the greatness of art in times past.”

In that post, I mentioned that a few years ago1 I wrote a series of articles for The Remnant2 about what happened to art in the 20th century, how did it turn so bad? And why does it seem like the destruction in every area of our civilisation; art, music, politics, religion, is all of a piece?

Because it is. It all came out of the same philosophical and political revolutions of the 19th century that led directly to the catastrophes of the 20th and 21st. I guess we shouldn’t have been surprised, since both its artistic and religious manifestations come with the same smell.

To understand why Annigoni and others were so outraged, so furious against the “avante garde” in art, one must look closely at what that movement was, where it came from and especially what it wanted.

I said I would repost3 this two-part series, so here we go…

What happened to art and when?

In a video the contemporary realist artist Robert Florczak talks about the trends of the last hundred years of modern art. What he describes is a deliberate and calculated drive to change the goals of art from the pursuit of the profound, inspiring and beautiful, to our current mania for the “silly, the pointless or the just purely offensive.”

An “installation” of a dirty, unmade bed; a “dress” made of slabs of rotting meat; a trio of tins of the artist’s faeces; a porcelain urinal titled, “Fountain”… a rock ... All are actual examples of this descent into nihilistic meaninglessness that has been made the standard fare in contemporary “art”. All of this, moreover, is rejected by the general public – who simply no longer go to art galleries – and all lauded by the art world’s elite.

But how did we get here? In one sense it was quite abrupt. In 1917, an artist and ideological change agent named Marcel Duchamp placed a porcelain urinal on a pedestal in an exhibition in New York, scrawled the word “fountain” on it and signed it “R. Mutt.” This “work” was at first rejected by the Society of Independent Artists who were running an exhibition of new works. After they were forced to accept it (Duchamp had had himself placed on the board) the Society tried to hide the piece at the exhibition, giving the opening for Duchamp’s ideological followers to stir up a controversy.

This publicity brought out the fashionable intellectuals defending it, thus launching the entire industry of modern art criticism whose role every day since then has been to praise every new invisible suit the latest Emperor of Art cares to don.

“Fountain” was reproduced several times by Duchamp in the ‘60s, and one of those copies still sits in pride of place at the Tate gallery in London. This object is regarded by art historians to be the turning point in 20th century art that ultimately rejected all the traditional canons of artistic excellence.

“Duchamp was by far the most successful of the artistic atheistic-leftist subversives. By 1913 he had coined the term ‘anti-art’…”

The occasionally cross-dressing Duchamp, perhaps ironically, had himself received the classical academic education in drawing and painting that he was to have a major hand in destroying. (He was later to denounce what he called “retinal art”.) But of course, Duchamp didn’t just come up with the idea one morning for “Fountain”.

Philosophical threads: “Dada” and Deconstructionism

It is always instructive to trace the philosophical lineage of such moments in cultural history and when one does, it becomes clear that these deeply atheistic and anti-traditional cultural revolutions came from the same sources and spread from there in concentric circles into the visual arts, literature, (in the person of the Bloomsbury Group in London) architecture, (“Le Corbusier”) and music (Erik Satie, et al).

Although he was not the first, Duchamp was by far the most successful of the artistic atheistic-leftist subversives. By 1913 he had coined the term “anti-art” for what he wanted, and was a moving force behind the movement later called Dadaism that was briefly trendy in Switzerland during WWI and then was spread throughout the western world.

Dada, explicitly intended as an ideological protest movement, was the origin of the idea that art must reject beauty and meaning, and that its primary goal was to shock and offend.

In 1916 Dadaism came onto the European scene at a trendy Zurich salon4 called the Cabaret Voltaire, founded by a group of German, Hungarian and Romanian Bolshevists and anarchists connected to the earlier avant-garde artistic movements. This “advance guard” of the left had fled to neutral Switzerland during the convulsions of WWI. Many of them stayed to found the post-war intellectual - or “anti-intellectual” - movements of the later 20th century.

They were rebelling against what they called “rigidity” and devotion to reality in traditional Academic painting. And in poetry and literature the aim was to break the connection between words and meaning.

Dadaism is described as an “anti-rational” or “anti-art” movement, associated with early Bolshevism, that proposes “the meaning of meaninglessness” in visual arts and poetry as a way of breaking down “bourgeois” artistic and cultural assumptions.

Later, this idea was to be taken up by the philosopher Jacques Derrida (b.1930) and turned into “deconstructionism” through which “western” ideas of logic and reason are subverted and eventually destroyed in academic philosophy.

Deconstructionism – that had its equivalent movement in painting and sculpture – has itself become a plague in secular academic philosophy and literary criticism. Both the small artistic circle of the Dadaists and the later massive swelling of philosophical deconstructionism owe their allegiance to Hegel, Freud, Heidegger and Sartre and the entire pantheon of modernist philosophical destructors.

“How does one achieve eternal bliss? By saying dada. How does one become famous? By saying dada. With a noble gesture and delicate propriety. Till one goes crazy. Till one loses consciousness. How can one get rid of everything that smacks of journalism, worms, everything nice and right, blinkered, moralistic, europeanised, enervated?”

The Dada Manifesto, Hugo Ball, Zurich, 1916

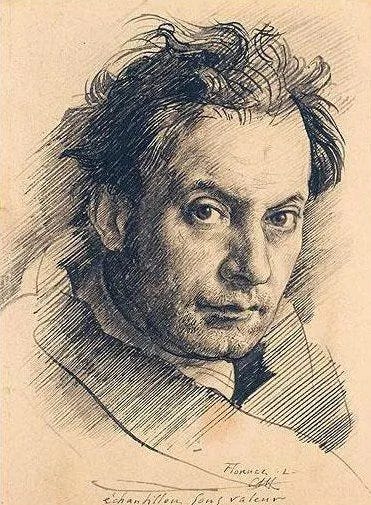

The Dada Manifesto gives an idea of the level of intellectual rigor and competence of the founders of the various movements in modern art. It was written in 1916 by the Cabaret Voltaire’s founder, the poet and failed actor, Hugo Ball (1886-1927). The name, Dada, Ball claimed, was chosen at random from a French-German dictionary and meant anything or nothing as the user chose.

“I shall be reading poems that are meant to dispense with conventional language, no less, and to have done with it. Dada Johann Fuchsgang Goethe. Dada Stendhal. Dada Dalai Lama, Buddha, Bible, and Nietzsche. Dada m’dada. Dada mhm dada da.”

“It’s a question of connections, and of loosening them up a bit to start with. I don’t want words that other people have invented. All the words are other people’s inventions. I want my own stuff, my own rhythm, and vowels and consonants too, matching the rhythm and all my own. If this pulsation is seven yards long, I want words for it that are seven yards long…”

Clearly, the content was beside the point.

Dada and Proto-Communism

Ball, who had been raised a devout Catholic, had been a young disciple of Mikhail Bakunin, the Russian revolutionary anarchist, Hegelian and rival of Karl Marx in the International Workingmen’s Association, the movement sometimes called the First International, the umbrella group of radicals, socialists and anarchists that was later to resolve into Soviet Communism.

Like many of the young ideologues of the late 19th and early 20th century, Ball later grew out of his radicalism and reverted to his earlier Catholic Faith living to the end of his short life in obscurity. But the damage was done, and the Dadaist followers he had gathered in Zurich took their “anti-rational” ideology of meaninglessness like a virus into the wide world of culture.

After escaping Zurich and being carried to Berlin and eventually to most of the rest of Western Europe’s cultural centres, Dadaism had served its purpose and fell out of favour. It was replaced with an apparently endless parade of various successive “schools” and “movements,” that students of Fine Arts must now memorize for their exams: Cubism, Modernism, Fauvism, Expressionism, Futurism and all the way to Andy Warhol’s “Pop-Art” soup tins and Tracey Emin’s postmodernist unmade bed.

Dadaism: “We began by shocking common sense, public opinion, education, institutions, museums, good taste, in short, the whole prevailing order.”

It was about politics, not art: “Everything had to be demolished.”

Its explicit nihilism – a fashionable sentiment after WWI – was expressed grandly by an academic as “a phenomenon bursting forth in the midst of the postwar economic and moral crisis, a saviour, a monster, which would lay waste to everything in its path... a systematic work of destruction and demoralization... In the end it became nothing but an act of sacrilege.”

The critique against it at the time was as ardent. A contemporary reviewer in American Art News described it as “the sickest, most paralyzing and most destructive thing that has ever originated from the brain of man.”

Dadaism – and its descendants in art trends – is normally described, by those whose narrative it helped to shape, as a “reaction to the horrors of World War I,” an assertion that doubtless remains a popular justification in undergraduate essays to our time. In reality, however, and like all such ploys that manipulate popular sentiment, the movement’s opposition to the war was opportunistic.

Its self-admitted purpose was not artistic at all but philosophical and political; its purpose was to take over the art and literature scenes and to push out and anathematize traditionalist opposition. The Dadaists were forthright about their goal. It was not to change art, but to demolish ideas and ultimately an entire culture.

“Dada is the groundwork to abstract art and sound poetry, a starting point for performance art, a prelude to postmodernism, an influence on pop art, a celebration of antiart to be later embraced for anarcho-political uses in the 1960s and the movement that lay the foundation for Surrealism,” said the foreword of a 2007 book of Dadaist poetry.

Hugo Ball expressed it, “For us, art is not an end in itself ... but it is an opportunity for the true perception and criticism of the times we live in.” Dada, in other words, was a coup d’état of deliberate cultural destruction, and one that we are still living with.

One of its originators, the Romanian Marcel Janco, said, “We had lost confidence in our culture. Everything had to be demolished. We would begin again after the tabula rasa. At the Cabaret Voltaire we began by shocking common sense, public opinion, education, institutions, museums, good taste, in short, the whole prevailing order.”

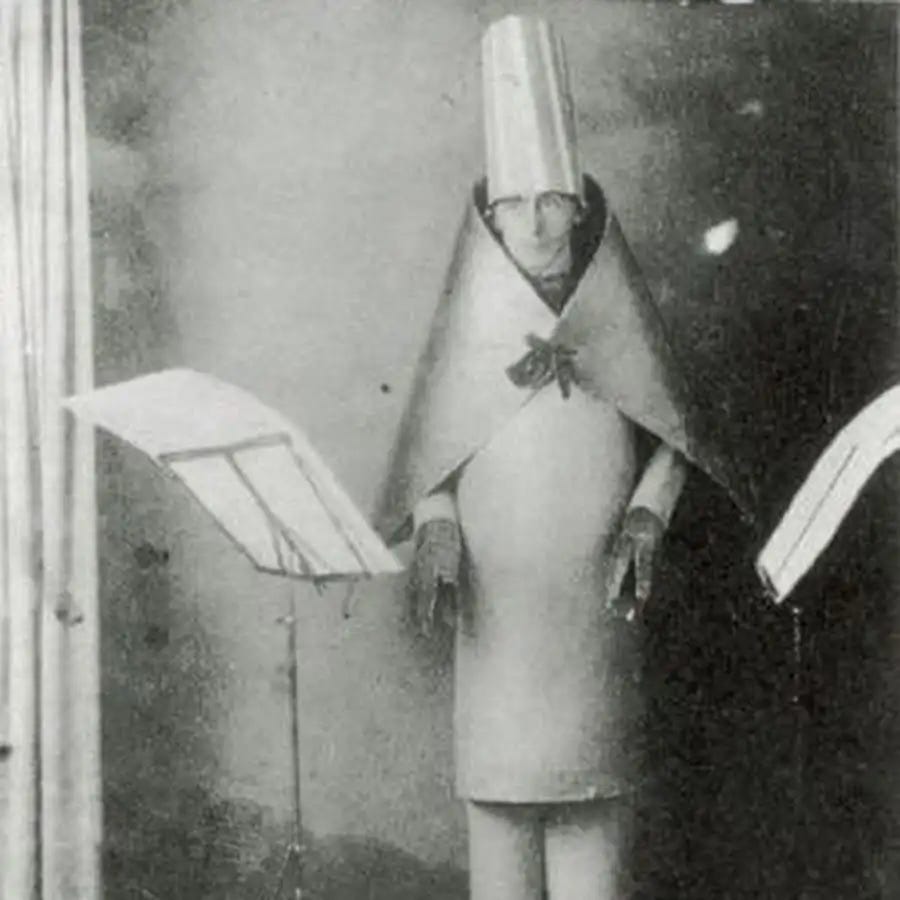

By 1920 in Germany Dada had already expressed itself in explicitly anti-Catholic terms. The Dadaist group in Cologne held an exhibition that year in a pub that included a woman dressed in a first Communion dress reading obscene poetry.

The Spread: Dada and the destruction of the world

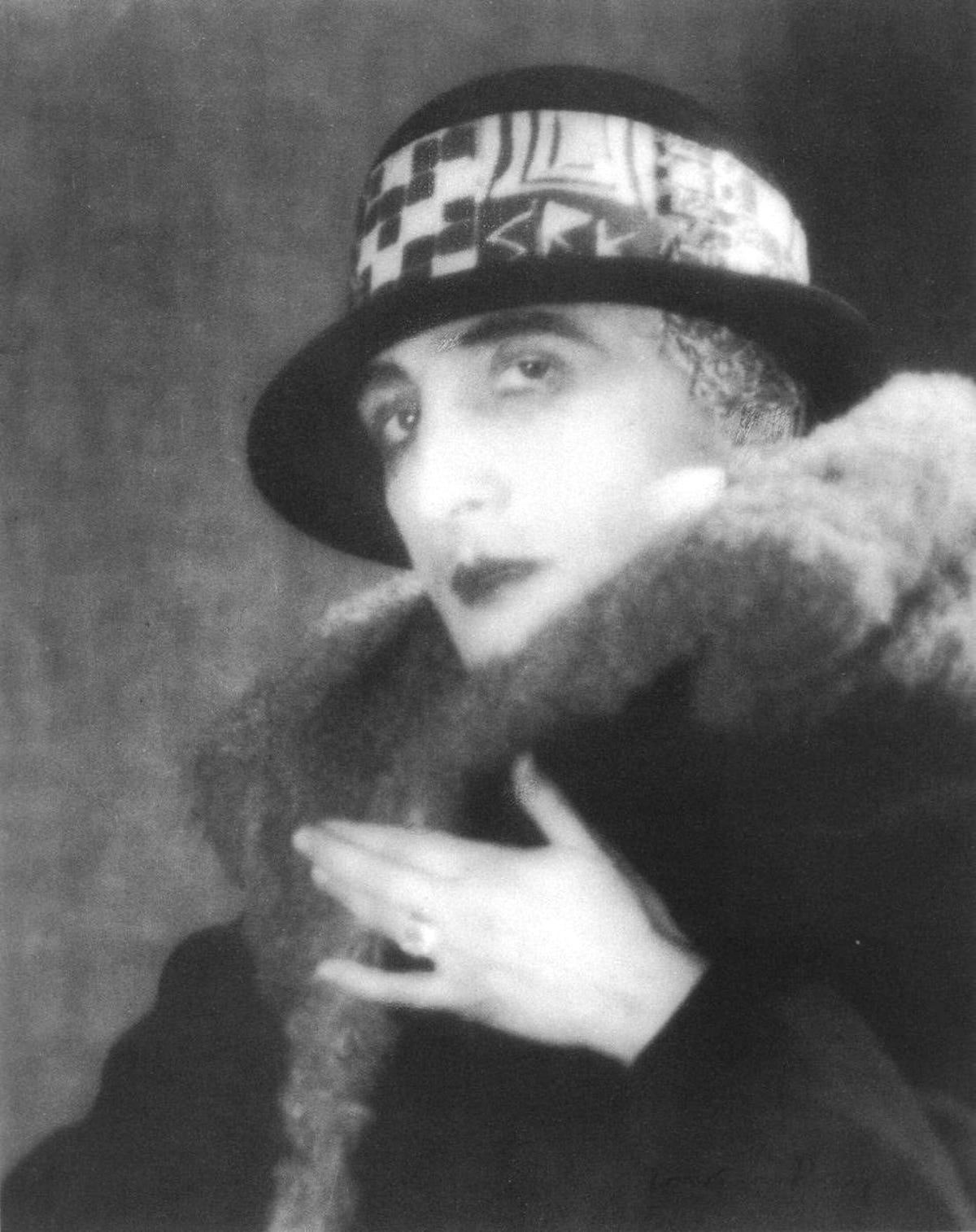

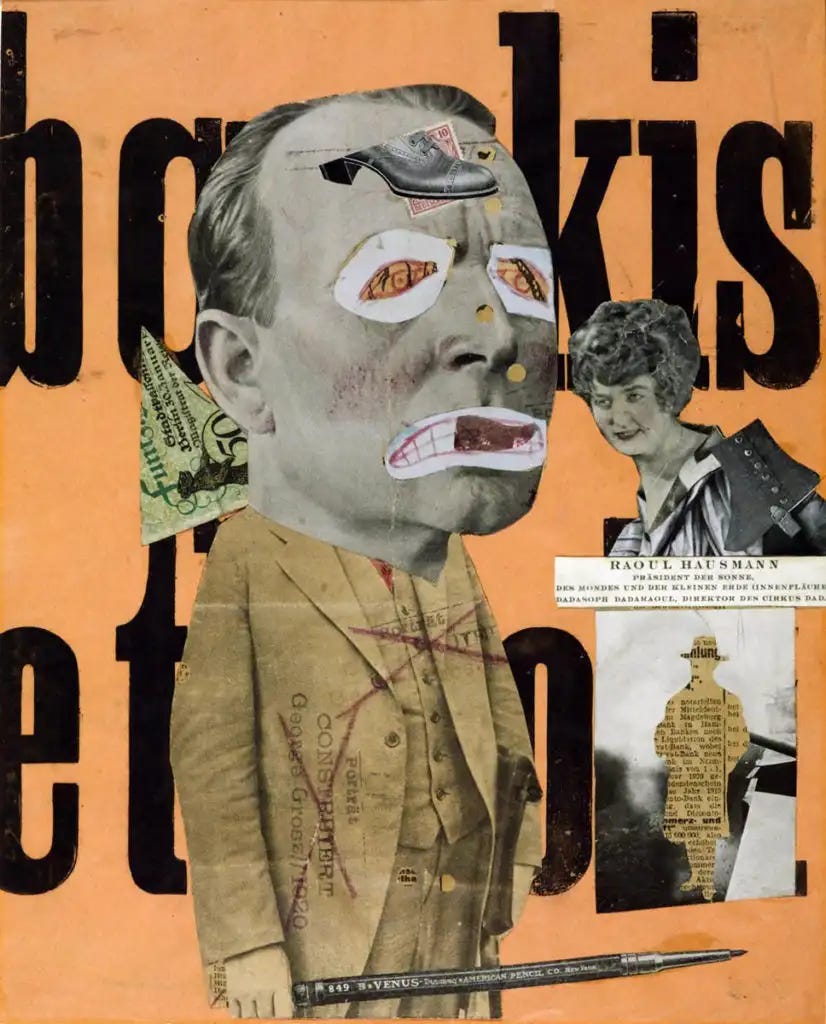

Duchamp was not the only ideological go-getter of the Zurich group, whose ideas were spread throughout the art world by a concentrated campaign. The Romanian Jewish modernist “performance artist” “Tristan Tzara,” – the pseudonym of Samy Rosenstock – emerged as the movement’s European leader, writing another, more comprehensible manifesto in 1917, and bombarding French and Italian artists and writers with letters promoting his ideology (the movement failed in Italy).

At the end of the war, the enthusiastic young Dadaists, their anti-rational manifestos in hand, re-dispersed to their native countries to begin the work of promoting it throughout western cultural circles.

The movement grew and by 1920 in Germany had already expressed itself in explicitly anti-Catholic terms. The Dadaist group in Cologne held an exhibition that year in a pub that included a woman dressed in a first Communion dress reading obscene poetry. It was closed down by police on obscenity grounds, but the scandal generated by the stunt had made its mark among the intellectuals. (The charges were dropped.)

Dadaism as a specific movement, of course, died off as it gave space for the succession of anti-traditional, anti-rational, anti-meaning art movements up to our own time. Its influence can be felt in nearly all areas of visual, plastic arts as well as music, television, film, even comic books, hair styles, clothing, interior design and our most popular styles of political protest.

And meaninglessness is big, big, BIG business.

The art world has never recovered from this coup d’état, and art students who want to learn the classical aesthetics, drawing, painting and sculpture skills – and who aren’t interested in philosophical or political indoctrination – had best give academic fine arts departments a wide berth. But the longing for beauty, as for goodness and truth, is worked into the human psyche in such a way as to be impossible to entirely eradicate.

~

Next: Part 2

Reality to the rescue: Richard Lack’s resistance and the Classical Realism revival

Thanks for reading to the bottom. I hope this has helped you understand what happened to our culture and world a little better. If you enjoyed it, why not click to subscribe?

You can also follow me - and donate to help - as I develop my painting work on my Ko-Fi page. You can follow my Facebook page here. And of course, I’m still shaking my fist at those damn kids to get off my lawn, on Twitter. If you would like to drop a few coins in the Paypal tip jar, I’d be most grateful.

February, 2016, to be exact. I’ve done some editing of the original piece.

For those readers who aren’t familiar, The Remnant newspaper is the most venerable of the US publications focused on the movement within Catholicism to restore the Traditional liturgy, the Mass as it was said from the 16th century to 1965, and holds that the changes made since the Second Vatican Council have been a catastrophic disaster.

This is an edited version. The original appeared in the Remnant’s print edition.

Cabaret Voltaire is preserved as a cafe and museum for the anti-art and anti-philosophy movements it spawned.

I just read Nihilism by Fr. Seraphim Rose and recommend it! So much I can see in a new light now, that you have also touched upon here.

Thank you Hilary, very informative. So am I right to conclude: Bolshevism was the revolution that wanted to destroy traditional politics, economics and society whilst its offspring Dadaism proudly sought to destroy culture, art and literature?

Whilst Bolshevism has been discredited as it proved to have real and disastrous consequences for everyone, the influence of Dadaism has lived on, maybe as it really only exists in the rareified atmosphere of the cultural elite, thus not impacting the daily life. Add to this, I suppose, that there is only so much a critic can write about a realist landscape or portrait (and if you can't write much, who willl pay you and how will you distinguish yourself) whereas with an abstract piece there is no end to what a critic can write as no one can prove them wrong or tell them they aren't qualified to comment or don't know what they are talking about. So abstract art is hept alive as it is a bottomless brunch for art crtics who couldn't draw a triangle themselves but can make a living writing tosh about meaningless art.

The Emperor really is wearing no clothes!