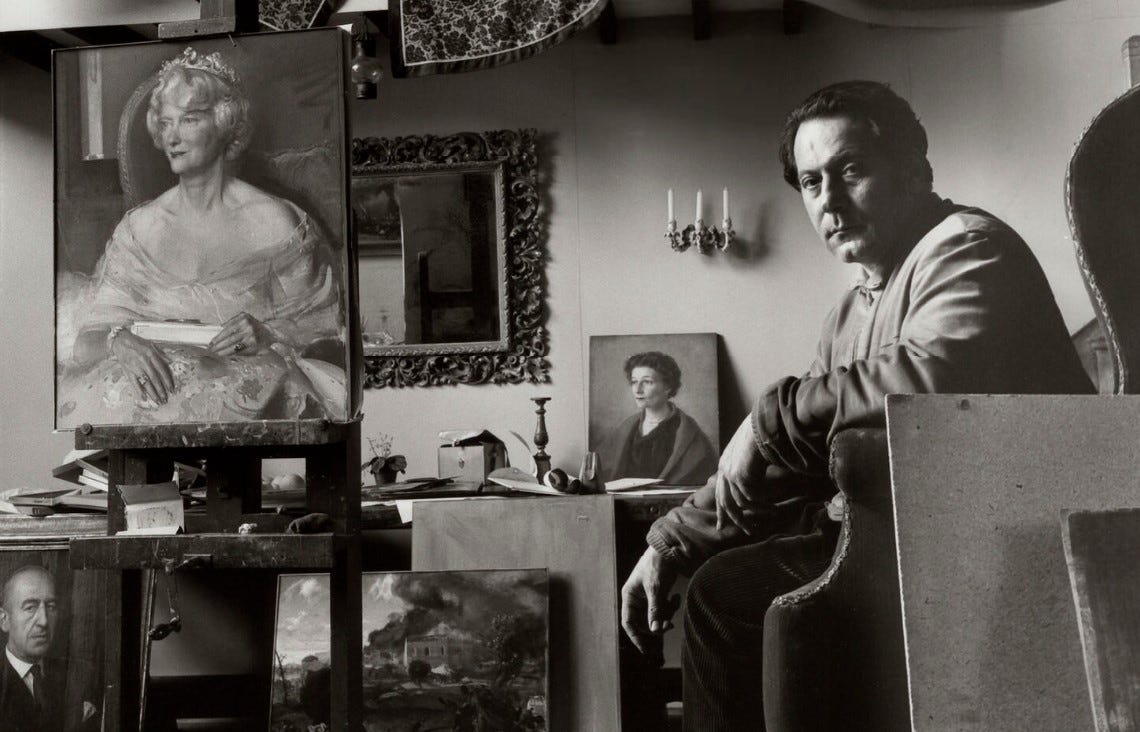

The painter and the queen spoke French to each other: Annigoni, despite having spent some time in England, still did not speak English well. At the time, he was forty-four, she was twenty-eight…

About this famous portrait, Annigoni wrote in his diaries: “I got up feverish this morning, and down in spirits. Invasion of photographers and journalists. Incredible banality of the questions. Everyone is impressed that the queen will come to pose in my studio…This portrait will be a difficult battle, and may God send me a good one.

A few days later: “Today, at Buckingham Palace, first meeting with the Queen. Intense, invincible emotion that lasts. I will not forget this day.”

“As a model, the Queen does not facilitate my task. She doesn't feel the pose, nor does she seem to care. And she talks a lot. On the other hand, she is kind, simple, and she never appears distant… The entire royal family - Queen, Queen Mother, Princess Margaret, Prince Philip and the children [Prince Charles and Princess Anne] - came to see the portrait. The mother is somewhat scrutinizing, full of charm, freshness, and surrounded by an emanation of deep sensuality. Many praises that I would say [were] sincere.”

Valentino Bellucci wrote that the painter wanted to “symbolize, through the sunny image of a splendid young woman who has just ascended the throne, all the hopes and expectations of a new era in English history after suffering and trauma of the Second World War.”

This post is free in full for all subscribers.

The Sacred Images Project is a reader-supported publication where we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art.

You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week. For $9/month you get a weekly in-depth article on this great sacred patrimony, plus extras like downloads, photos, videos and podcasts (in the works), as well as voiceovers of the articles, so you can cut back on screen time.

Today’s featured shop item is the note book with the Hans Memling St. Michael the Archangel on the cover, which you can order here:

If you’d like to see more of my painting and drawing work, and maybe order a print or other item you can find it here:

If you’d like to set up a monthly patronage for an amount of your choice, you can do that here. If you sign up for more than $9/month, you get a complimentary paid subscription to the Sacred Images Project.

The Other Art World

The other day, under a Facebook post from a friend praising a certain painter for what my friend thought his surpassing skill at still life, I commented:

“Since the start of the revival of training in classical academic skills in the 1980s, there are a great many painters out there doing contemporary realism to an extremely high standard (higher even than this), and it's a great pity that they get so little attention from the general public, who stumble across them from time to time.

There's a whole movement that is gaining ground only slowly because of the professional art world's continuing obsession with the gargantuan pile of horse manure (often literal) that the big name (government funded) galleries persist in foisting onto the public. The result being that classical realist painters can't get recognition except by accident, and the public continues to be disillusioned and demoralised.

“Honestly, as good as this might seem to a person unaccustomed to looking at good painting, it's really only in the middle range.”

The fact that the artistic counterrevolution has been going on since the 1940s and is still mostly unknown to the general public will tell you how much damage, how much demoralisation, has already been accomplished. The same ideological forces, that first put a porcelain urinal on a plinth and called it art a hundred years ago, maintain their grip today on “mainstream” cultural reportage.

The Modernists own art, and you aren’t allowed to know what they won’t tell you. A great many people have just written off art as hopelessly lost behind cultural enemy lines. Which is why they often react with exaggerated astonishment - and gushing praise - at seeing mere competence at rendering an image of a fruit bowl.

A few years ago, for the Remnant, I wrote a series of articles on where that kind of “Modern Art” came from, titled “The man who saved art,” demonstrating that the destruction of art grew out of the same philosophical diseases that resulted in so much destruction within the Church. But much more to the point, that series was about how the whole multi-billion-dollar, global private joke was being resisted and brilliantly undermined.

We all know what “modern art” is about:

“An ‘installation’ of a dirty1, unmade bed; a ‘dress’ made of slabs of rotting meat; a trio of tins of the artist’s faeces; a porcelain urinal titled, ‘Fountain’… a rock ... All are actual examples of this descent into nihilistic meaninglessness that has been made the standard fare in contemporary ‘art’”

How did it happen? In the briefest possible nutshell, the world of professional culture-mongers, the institutions that buy it and publications that talk about it, were taken in a bloodless coup d'etat while the world was looking the other way, during the first world war.

It started with an unpleasant little man named Marcel Duchamp.

Subversion is still all the rage in a certain set.

“Fountain” was reproduced several times by Duchamp in the ‘60s, and one of those copies still sits in pride of place at the Tate gallery in London. This object is regarded by art historians to be the turning point in 20th century art that ultimately rejected all the traditional canons of artistic excellence. After this point, such “avante garde” pieces started to become at first forcibly accepted by mainstream galleries and art promoters, to eventually become compulsory, almost entirely eclipsing traditional art and instruction. Duchamp is still hailed by art critics as one of the three most important figures of 20th century art, with Picasso and Matisse, who brought us all that still plagues the art scene – particularly “conceptual art” that artistic branch of philosophical Nominalism that insists that any object is art if the “artist” says it is.

But in the late 1960s, in the face of the growing and spreading lawlessness in the art world, one man in the US decided to risk ridicule of the professional scoffers and push back.

In 1969, an obscure American painter published an essay titled, “On the Training of Painters,” that was perhaps the first time anyone had the wherewithal to stand up in the face of the radicals and call them naked shysters.

Richard Lack, who had been the last surviving recipient of the ancient system of one-to-one training in classical, academic drawing and painting techniques, wrote, that in the world today, there are “few living painters who could execute a figure composition [that] would stand favourable comparison with even a second-rank nineteenth-century work.”

But I should have said that it was the last man in the English-speaking world. The pushback in Italy had begun 20 years before.

Annigoni’s Defiance: transcendence

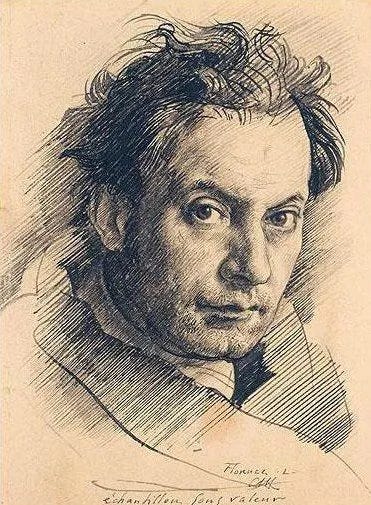

Famous for his portraits - and called the “painter of beautiful women - Pietro Annigoni (1910 - 1988) was a traditional Christian religious believer as well as a vocal opponent of contemporary social and cultural trends in art. Born in Milan, he grew up in Florence attending the best possible schools. Nevetheless, even in the 1920s, he had to spend hours in the national library studying Leonardo’s drawings to teach himself classical techniques. Before World War II he had already met with some success, showing a devotion to “realism,” in his first exhibition in 1932.

At the peak of his career in the late 1940s and 50s he was a world-famous portraitist with commissions to paint royalty, US presidents and dignitaries of all sorts. His works are kept in the National Portrait Gallery in London and the Vatican Museums.

But by his own account the painting that meant the most to him were his religious works, like this series of frescoes in the shrine church, the Sanctuary of the Madonna del Buon Consiglio in Ponte Buggianese. His final period was mainly devoted to sacred art.

In his diary, Annigoni wrote of the above painting: “In the evening, the sunset from Mount Carmel. Towards the sea, for a few moments, two incandescent clouds (one, probably, of smoke) meet and draw an immense cross of fire in the sky.”

Against the erasure of memory

As Annigoni’s fame grew, he found himself positioned, with his devotion to classical technique, subjects and styles, as the leader of a counter-revolutionary movement opposed to the trends in the professional art world. Annigoni and his colleagues were painting, one art historian writes, “against everything that had happened from post-impressionism onwards, against the avant-gardes, against the École de Paris.”

Worse even than the erasure of traditional technique and ideals in the professional art world was the spread of the Modernist ideologies into the universities and prestigious art schools around the world. Over the last 100 years, the ideology has not only made it unfashionable to show, sell and buy traditional art, but nearly impossible to learn how to make it.

One of Annigoni’s students, the American Canadian2, Michael John Angel, the founder of one of the leading new private schools of contemporary realist drawing and painting in Florence, said it was Annnigoni who taught him that “the collapse in standards of finished artworks derives from the collapse of training in technical ability in major art schools and universities.”

Since the early 20th century, art schools consider the pursuit of excellence in craft to be hopelessly obsolete, outdated, and even philosophically offensive. These schools, he says, “are populated entirely by an assemblage of people holding meaningless credentials often from top universities that have bestowed upon them virtually none of the skills or knowledge needed to transmit the essential disciplines of drawing and painting.”

Finally, the disdain and ostracism of students and teachers interested in the traditional ways resulted in the near erasure even of its memory in mainstream art schools. A student approaching an instructor in university now asking to learn to draw like Leonardo is not only risking ridicule, and even expulsion, but is wasting his time; the teachers no longer have the skills to teach.

Annigoni’s Manifesto

Seeing the way it was going, in 1947 Annigoni published a letter accusing the established “avante garde” professional art world of perpetrating a gigantic fraud, the work of a “decaying society” that is “sterile” and an “expression of an age of false progress”.

The “Manifesto of Painters of Reality” said:

We are neither interested nor moved by the so-called “abstract” or “pure” painting, procreated by a decaying society, which is empty of any human contents and has retreated into itself, in the vain hope of finding a substance in itself.

We disavow all contemporary painting from post-impressionism till today, regarding it as the expression of an age of false progress and a reflection of the dangerous threat that looms over mankind. On the contrary we reaffirm those spiritual and moral values without which painting would become the most fruitless exercise.

Painting reality, he said, was to be a “moral” exercise that “should be filled with the same faith in man and his destiny, that had made the greatness of art in times past.”

“Each one of us has spontaneously addressed himself to reality, the first and eternal source of painting, confident to find his own expression in it.”

Instead of attempting to foment yet another revolution in art, the manifesto called for realist painters to “simply keep on with our mission of true painting” to be “understood by many, not just a few ‘sophisticated ones’.”

One of the best experiences of my own atelier training in Rome was a master class by this chap, Jordan Sokol.

Saved by a thread: the ateliers and the Classical Realist Revival

From a handful of men defying the establishment a movement was finally born and grew. Fred Ross, the Founder and Chairman of the Art Renewal Center, wrote that by 1980 there were only seven private ateliers - schools where a student undertook an intensive apprenticeship in the craft of painting under a master artist - in the whole world. And all of them had been started by students either of Annigoni or Ives Gammel3

To this day, the atelier movement of Classical (or Contemporary) Realism has spread all over the world, with private atelier classes in traditional craft techniques of drawing and painting, those used in professional studios for centuries until 1917. From that precarious seven, by 2016, the number had grown to over 100, training thousands of students to high professional standards.

It is significant that Annigoni’s determination to “simply keep on” doing “true painting” resulted in a movement and not another violent revolution. A handful of students labouring painstakingly over years of in-person instruction, dedicated to learning and developing highly rarefied skills, are usually spending too many silent hours standing in studios to have time to waste fomenting ideological rebellions. Most atelier students are indeed refugees from these schools of radical-but-mainstream ideologies, having either been ostracised as heretics for their love of beauty and craft, or disillusioned by the emptiness and disdainful scorn inherent to the rhetoric itself.

No, the Classical Realist revival is a true underground movement that grew up through the force of its truth under pressure from every direction. It is propagated by individuals deciding to devote themselves - often for life - to something greater than themselves, to a lifetime of learning and honing of skills, widening of knowledge and deepening of Annigoni’s “spiritual and moral” artistic values.

Since the urinal incident in New York, many are growing weary of Modernia’s endless parade of degrading, anti-rational, anti-human and often extremely silly insistences. We are bullied and shouted at and used as unwilling ideological test subjects on every front for an increasingly unhinged elite class, whose loathing for us becomes more manifest by the day.

But as the demands of the culture wreckers become more bizarre, more voices are being heard opposing the systematic dismantling of our civilisational norms. There are now enough people being pushed out of nearly every institution, both brick-and-mortar and virtual, that the solution is starting to become obvious: start your own. Believe the evidence of your eyes; the emperor isn’t wearing a damn thing. Stay determined to simply keep doing the thing you know is the true thing.

Over the next few days, I’ll be reposting that series of articles from the Remnant, with the kind permission of the original publisher.

Many thanks to alert reader, Peter, for the correction on this. Also, Yay for our team!

R. H. Ives Gammell. 1893 -1981. The American academic painter, writer and teacher who taught Richard Lack and also wrote against the Modernist movement.

Great article. The exact same thing happened in music schools and conservatoires where radicalised professors encourage all kinds of atonal rot that the public does not want to hear, and yet the radicals control all the prime positions so act as gate keepers.

Re modern art, I subscribe to a very witty quarterly periodical called The Jackdaw which keeps a very close eye on trends in modern art and offers some trenchant comments. Well worth supporting.

Great piece, I spent most of my life assuming I didn't care for the visual arts, when in reality it was the art being pushed by bad actors.