Ecce Agnus Dei: 13th century Umbrian panel crucifixes

The Franciscan answer to the Catharist heresy: Christ is truly fully Man and God

When you want to get off the beaten tourist trail in Italy, come to Umbria. We have, among many other under-sung treasures, one of the most captivating art forms anywhere, in the churches and museums of every town; the 13th century - “Duecento” - panel crucifixes of Umbria and central Italy.

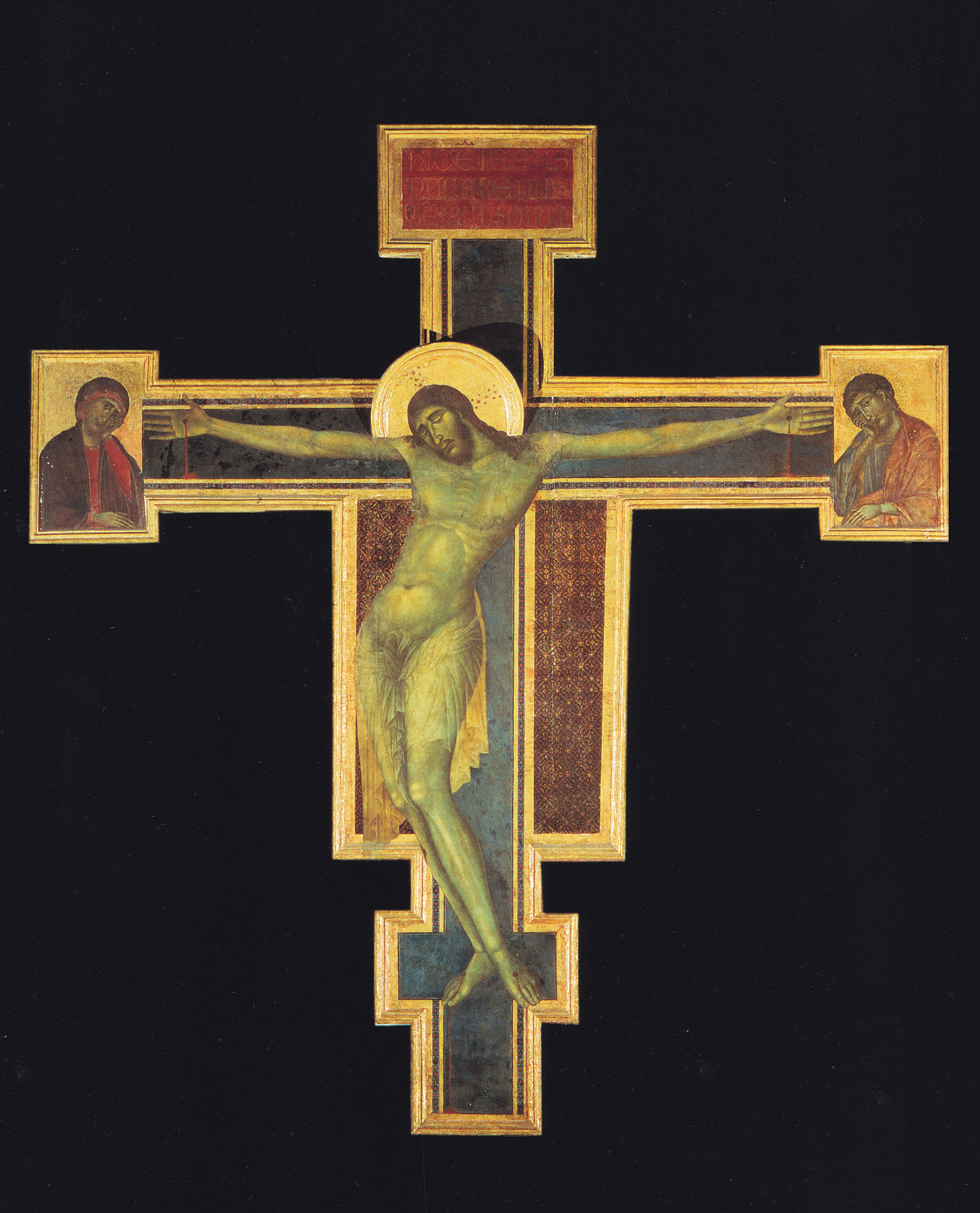

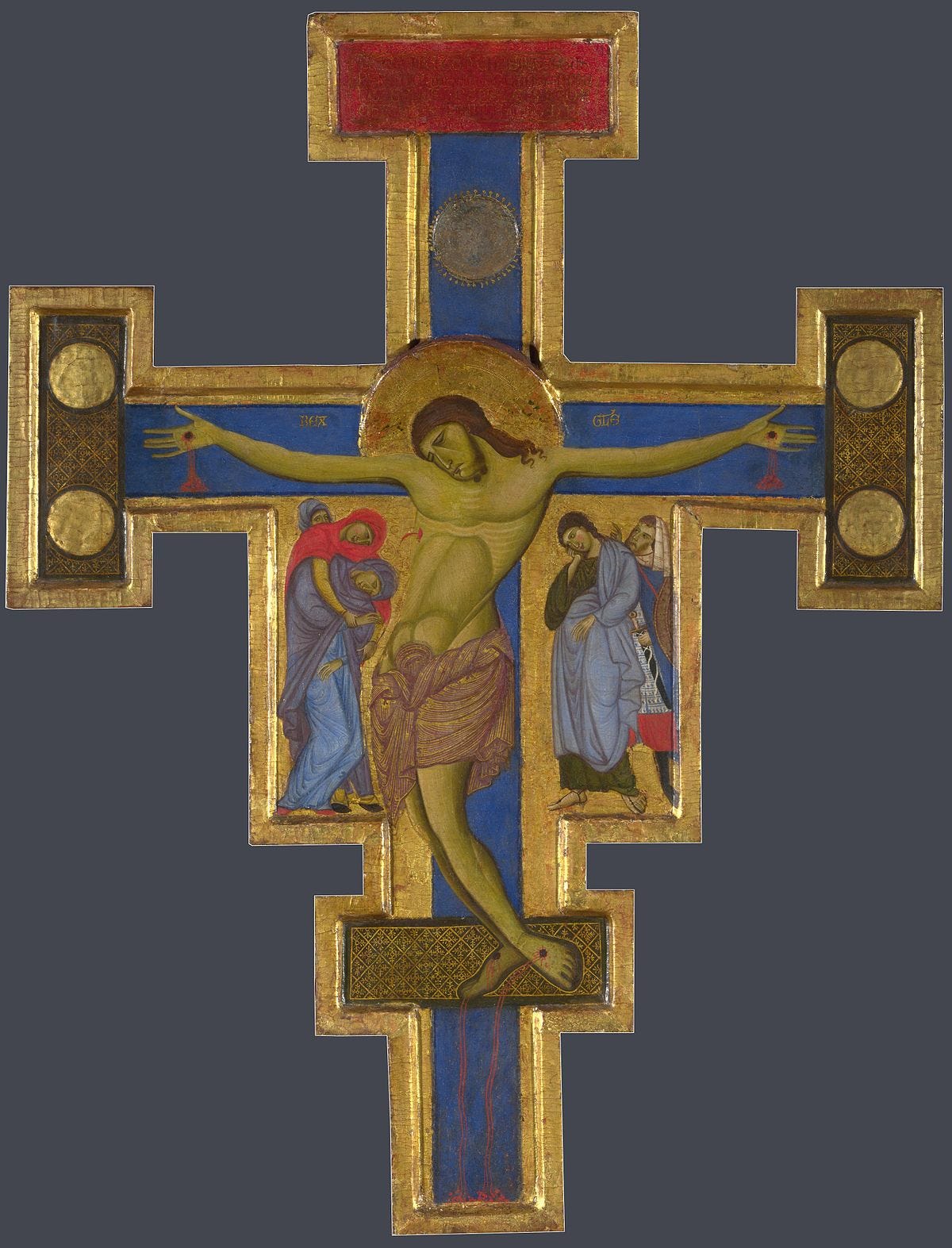

I’ve been captivated by these magnificent things since I came to live in Umbria where they are a common sight in the older churches. This one, by Cimabue, is considered the very pinnacle (and tail-end) of the genre.

This post has been de-paywalled, so is free in full for everyone.

The Sacred Images Project is a reader-supported publication where we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art.

You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week. For $9/month you get a weekly in-depth article on this great sacred patrimony, plus extras like downloads, photos, videos and podcasts (in the works), as well as voiceovers of the articles, so you can cut back on screen time.

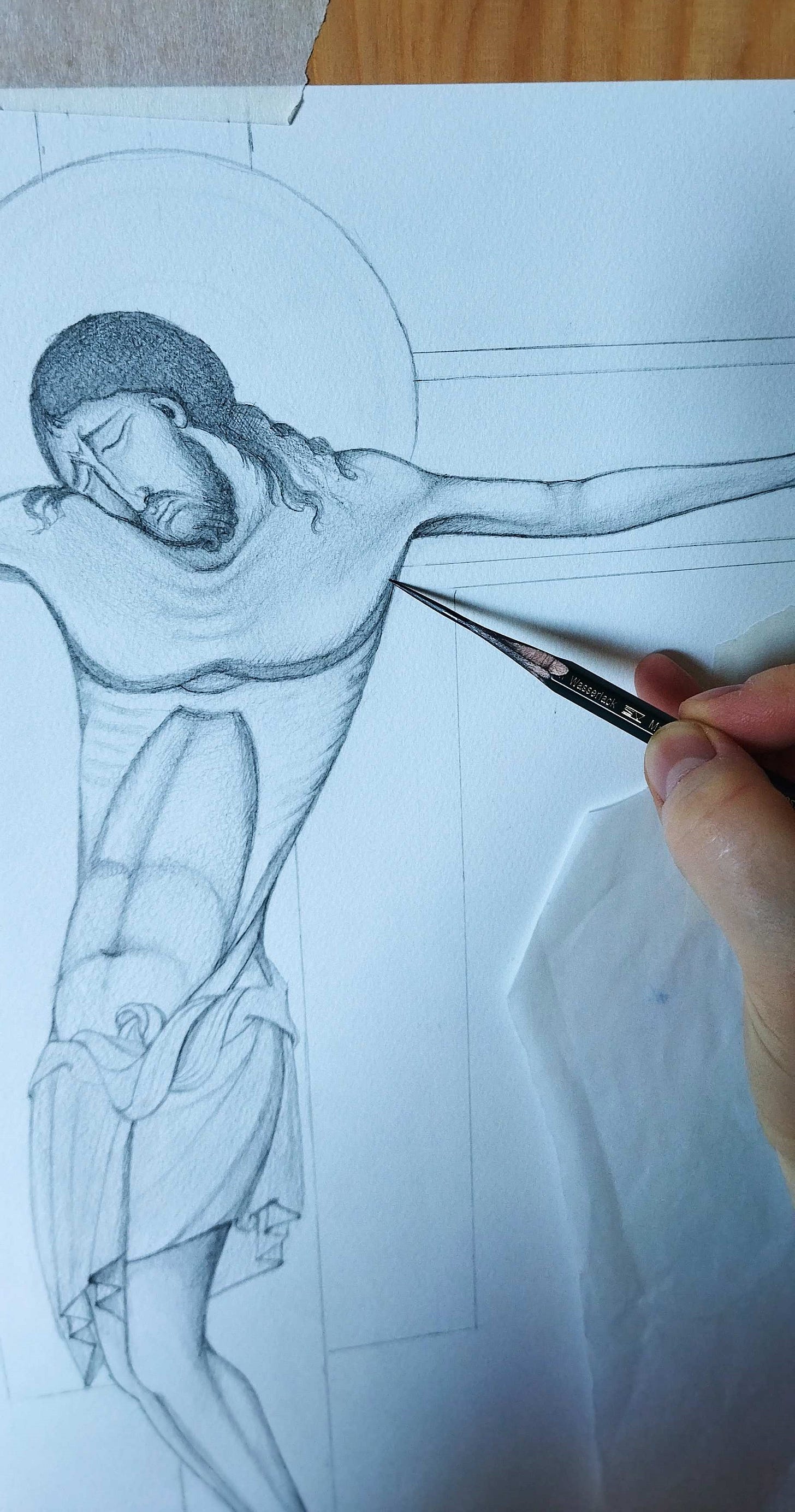

Today’s featured shop item is the drawing I did of a crucified Christ in the style of the Umbrian panel crucifixes, titled, Christus Patiens, which you can order here:

If you’d like to see more of my painting and drawing work, and maybe order a print or other item you can find it here:

If you’d like to set up a monthly patronage for an amount of your choice, you can do that here. If you sign up for more than $9/month, you get a complimentary paid subscription to the Sacred Images Project.

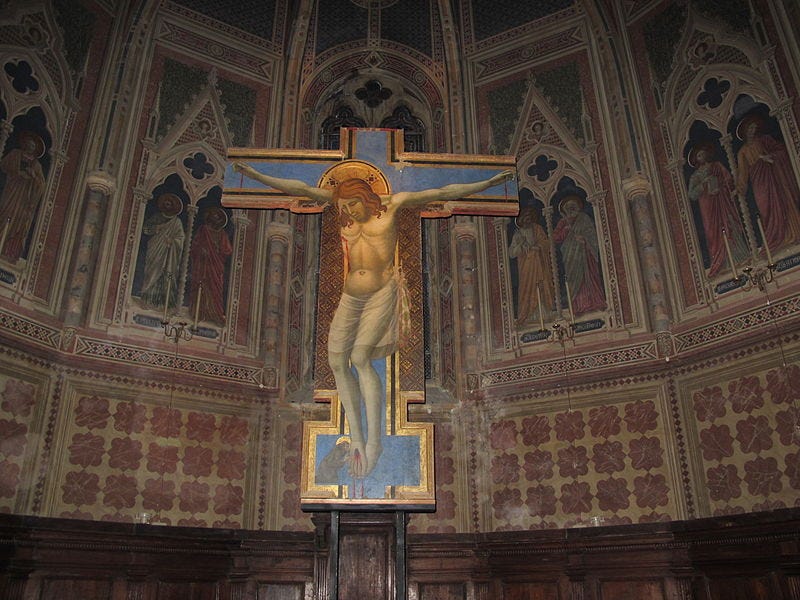

This one, by Giotto, hangs above the sanctuary in the church of Sant’Andrea in Spello, a little medieval town one train stop before Assisi (starting from Rome). The first time I saw this arresting work was during a pilgrimage Mass. I’d had no idea it was there, just hanging above the altar where it had been for hundreds of years. And this is the joy of Umbria; it’s not Disneyfied, not a tourist museum; the art painted for the churches is still in the churches it was created for.

But simpler, older and more homely versions of this genre of crucifix are scattered all over central Italy.

This week I started a preparatory drawing in this style, with a mind to make it available for prints and as the basis of a painting. In the process I’ve learned there’s a lot to this style and its significance for the spiritual life, for the development of medieval mystical theology, and even the historic place of “orthodox” sacred art in combatting error and heresy.

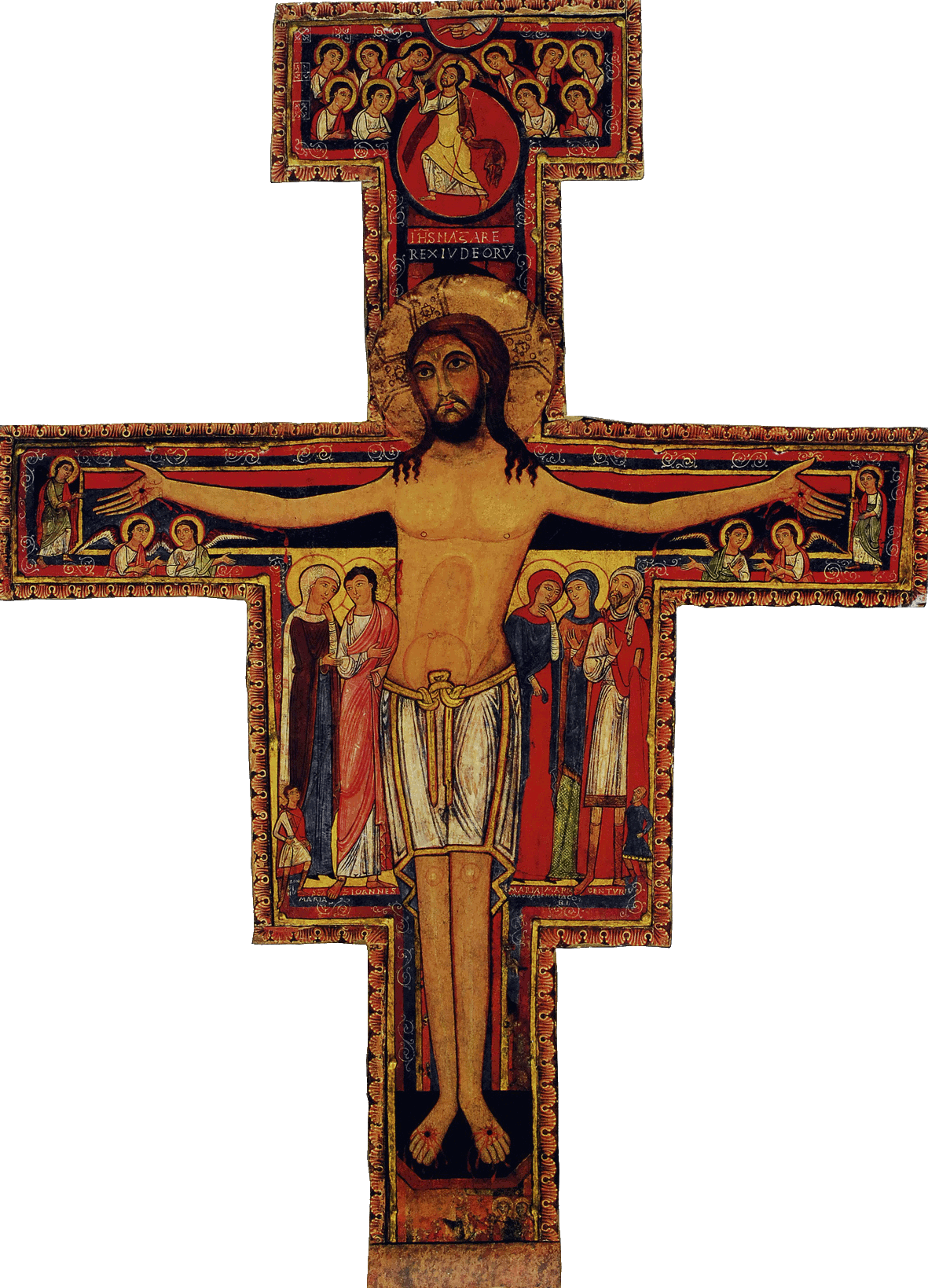

An early 12th c. panel icon that is a crucifix: the cross of San Damiano

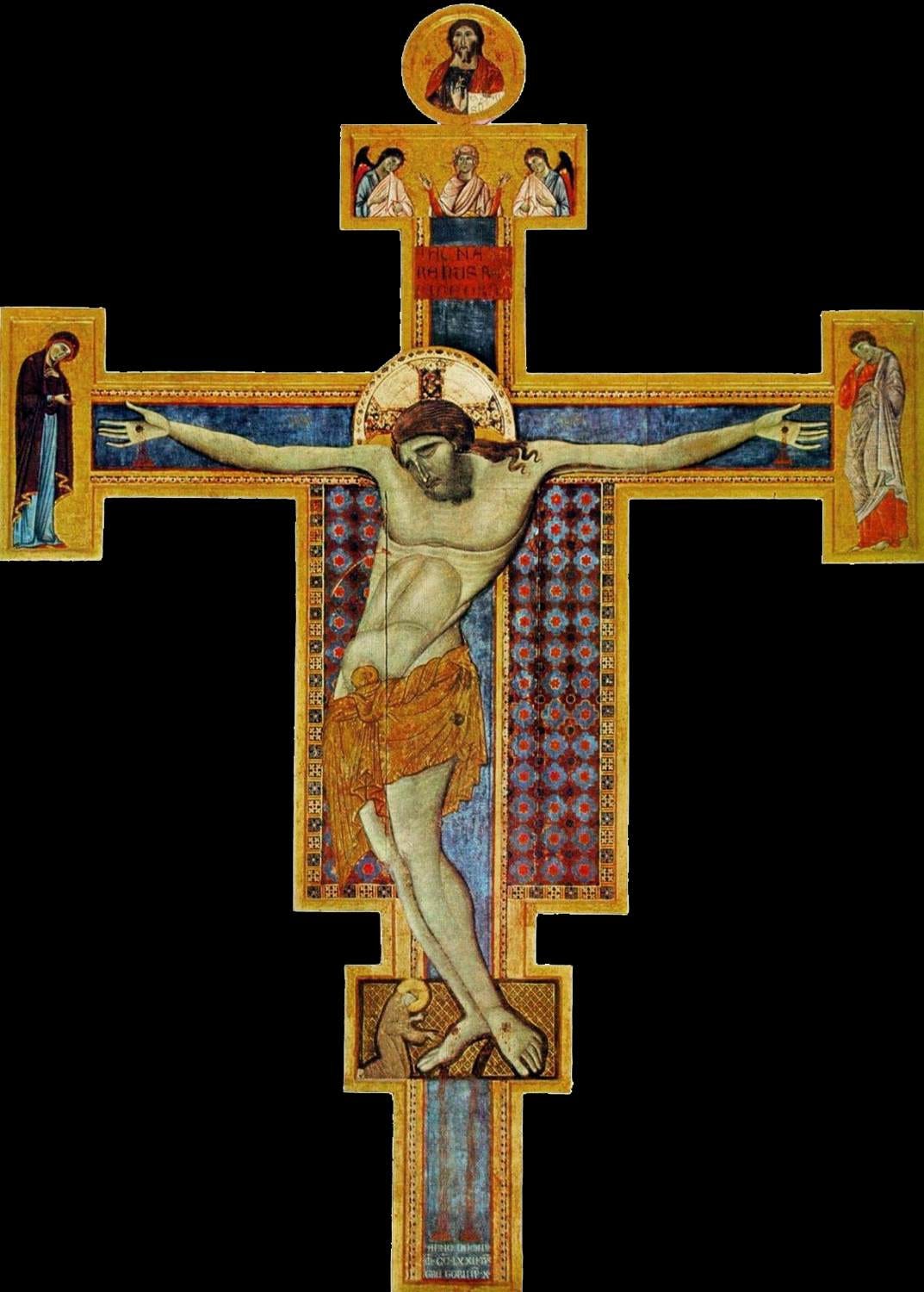

Of course, everyone recognises the famous San Damiano Crucifix, so closely associated with St. Francis of Assisi.

Apart from its miraculous history, the San Damiano Cross is one of the best ways to introduce the artistic category of “Italo-Byzantine”. It’s a fusion of Byzantine (Greek) and Western European (Gothic/French) styles, with stylised, linear, symbolic figures arranged symmetrically on a flat plane, without a “realistic” depth of background. The paintings were intended not as depictions of events and persons as they would have appeared to the eye in history (“naturalism”) but symbolically, like words and phrases in a visual language that tells a particular story, already familiar to the viewer.

Painted by an unknown artist in the early 12th century - probably 1100 - it was taken in 1257 to the Basilica of St. Clare in Assisi where it remains today, suspended from the vaulted ceiling of a side chapel. 2.6 meters (8.5 feet) tall and 1.7 meters (5.6 feet) wide, it’s typical of the style for its size. The stiffness of the figure of Christ marks it as an early example of the genre, more strictly Byzantine than Italo.

As is typical of this style, it is a kind of tableau of the scene of the crucifixion; the Blessed Virgin and St. John the Beloved Apostle mourn the passion at the foot of the cross. On the other side are are Mary Magdalene, Mary of Cleopas and the centurion (carrying the sign), the one who in the Gospel according to Mark proclaims: This is truly the Son of God and who had asked Christ to heal his servant (who can be seen at his feet). On the lower left is Longinus with his spear, halo-less here but venerated as a saint in the East. Above Christ’s head He is depicted again ascending into heaven surrounded by angels. Above Him we glimpse the hand in a posture of blessing that is the traditional way of depicting God the Father in Byzantine iconography.

At the same time, while it emphasises Christ’s humanity in His crucifixion, depicting His wounds and blood, this is not a broken, defeated man, but the Logos who is alive after His passion, strong and upright, standing firmly on both wounded feet; He is both crucified and risen. This is the suffering human Christ at the same time as God, triumphing over sin and suffering and death itself.

In the later period, the panel crucifix has become a place of profound emotional interaction with the mystery of the death of Christ and His redemption. The figures are rounded and lifelike, the blood pouring from the wounds splashes like spilled wine against the inner edge of the frame. Christ is depicted as fully fleshy, corporally human in every way. And now, as already dead, eyes closed.

The graceful linearity of the figures - that long beautiful S-curve that was highly typical of the 12th century development - and expressiveness resembles a dance. This is the genius of medieval Latin iconography, to produce a work depicting the grief of death and human vulnerability as a redeemed reality in the sacrifice of Christ, beautiful in its terrible, unflinching confrontation with suffering.

The Virgin swoons from her mystical participation in the agonising death, supported in the very moment of a faint by Mary of Cleopas. John the Beloved Apostle is lost in grief, while the centurion gestures toward the dead Christ in a shocking moment of personal revelation: Truly this man was the son of God.

At the same time, it is a more obviously beautified object, as a crucifix, than the earlier style, a more intense, poignant composition with fewer figures, pinpointing the exact moment of the death of God, the vibrant, jewel-like colours of the semi-precious mineral pigments (the ultra-expensive ultramarine from Afghanistan) and a great deal of gold. This is no longer merely a narrative of the life of Christ, but the singular pivot of human history, the moment when the angels wept and Satan triumphed, only to find himself defeated utterly.

Here is the literal, physical blood of Christ - the sacrificial Lamb of God - poured out for all humanity. Fully God and fully man.

Umbrian panel crucifixes and the spirituality of redeemed suffering in Christ

These icons were in the line of a movement that started in the 12th century of showing the physical and real suffering and death of Christ on the cross that led to the naturalistic depictions of the crucifixion we’re familiar with today. The intention is to generate an emotional response of pity, empathy, sorrow and repentance in the viewer. And this is part of a greater spiritual movement that was later to be popularised by the new mendicant orders, Franciscans and Dominicans, who emphasized the importance of Christ's human and physical suffering and our own ability to “enter into” and participate in it through our affections. Of course, the creation of sacred art is a key component of this kind of evangelisation.

As such, the Umbrian panel crucifixes represent one of the most important examples of how Christian sacred art is not merely decoration, but a potent form of visual theology as important as verbal preaching. They speak to us from a time when the human person was not thought to be a collection of disparate, compartmentalised aspects: intellect, emotion and physicality formed an inseparable whole.

Iconography is also not strictly didactic. Icons can teach or at least support and supplementing the teaching of doctrine. But their significance is more about creating an emotional, non-intellectual, bond between the viewer and the person or scene depicted. Christians see the crucifixion of Christ in these works, depicted in its bloody reality, but in a style of great beauty and flowing, linear, geometrical symmetry - indicating that all this, even grief and suffering, are part of the greater plan of the benevolent God. They are urged to contemplate His sacred humanity and the concrete reality and efficaciousness of His sacrifice for the redemption of sins.

The Umbrian crucifixes and the Cathar heresy

As such, the artistic development of these paintings over the following 200 years would be part of a larger and permanent change in the way Christians thought about Christ, their ideas of having a genuine affective relationship with a real person, who knew pain and understood them at a visceral level. The Italo-Byzantine and Duecento panel paintings showing Christ in agony only intensified as more natural looking figures were created.

And this movement, in both spirituality and art, is thought by some scholars as a response to the materialist ideas of the Cathar heresy1 that was spreading in Northern Italy and southern France at the time. In the early 12th century the idea that Christ was just a man and His death was of no redemptive significance, were growing.

The Cathars adopted the ancient Manichaean dualistic ideas of two gods; an evil god who created material reality and a good god who created spiritual beings like angels and human souls. The soul was entrapped in the material body and had to be released by a process of spiritual purification and ultimately death. Catharism rejected Catholic sacraments and authority, including the Bible, and its popularity ultimately threatened the political and economic stability of Europe.

Of course this all meant that the Cathars also rejected the redemptive value of the crucifixion, holding that Jesus was just a human being, perhaps inspired by the Holy Ghost, and that the only way to be “saved” was to free the soul from the evil material world.

These crucifixes are an artistic representation of the underlying meaning, beauty and depth of Christian theology of the redemption from sin effected by Christ’s voluntary death on the cross. As these ancient errors grow once again, and the materialism that spawned them crushes souls again, a renewal of the meditation of the crucifixion with these beautiful images could be a part of the solution.

Also called the Albigensian heresy, Catharism is a resurgence of the Manichaean ideas that date to Imperial times. In his youth, St. Augustine of Hippo, 354-430, was attracted by the Manichaean sect. And in our own time ideas central to the Catharist ideology are prominent once again… Bad ideas never seem to die.

Thanks for this, most informative; I knew nothing about these portrayals of the crucifixion.

These images deeply move me, especially the one with "The Master of The Blue Crucifix." Thank you so much for sharing these for our contemplation.

I find it curious that none of these images display the crown of thorns. Is there a theological reason for this or was it just too much blood for the time?