Friday Goodie Bag for Sept 27: Narrative Realism & What "The Chosen" Can Offer the Imagination

Below the fold: "Missa Pro Defunctis" - the traditional Catholic funeral rite takes life and death seriously

We are not angels: what naturalistic art can help us do

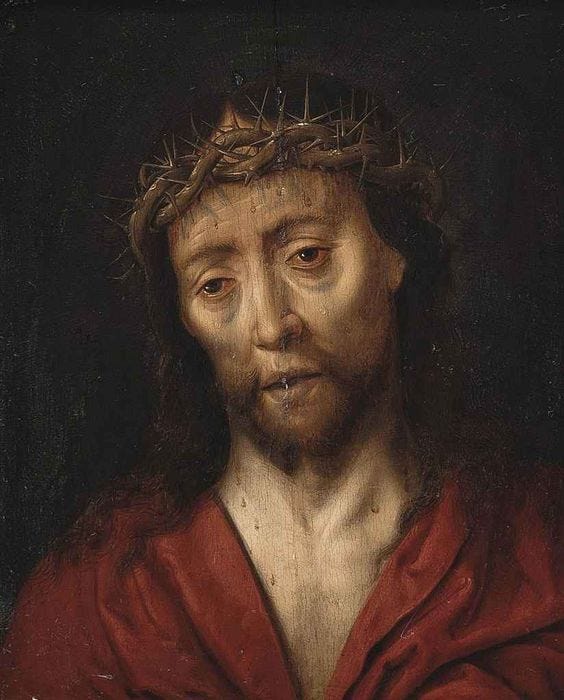

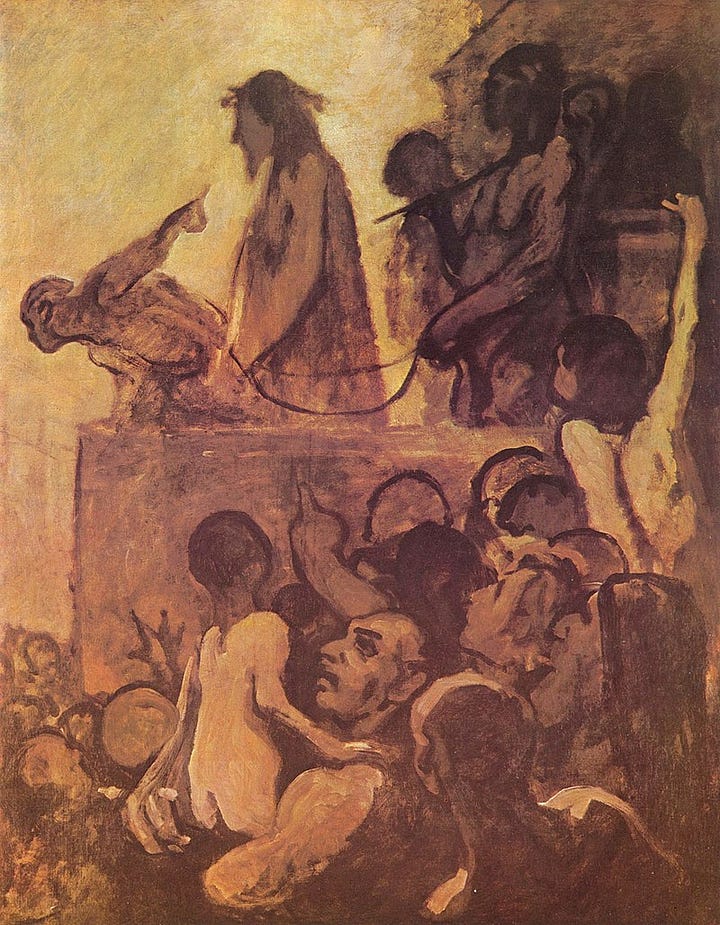

A major thesis of this site has been that narrative realism in Christian art is radically different in purpose from the ancient canons of Byzantine art and the Romanesque and Gothic styles that developed from it. I’ve critiqued the shift towards visual realism (what the Byzantines call illusionistic naturalism) that began in the Renaissance as a significant departure not only in style but in intention, and theological meaning.

I’ve argued that such works are not, in the ancient sense, “sacred art” at all, but rather illustrations shaped by contemporary aesthetics and philosophies. These images depict what the artist or patron imagined biblical events or people might have looked like, but they depart from the deeper spiritual functions of authentic sacred or liturgical art.

However, I want to acknowledge that narrative realism does have its value, particularly in its ability to make sacred history imaginatively accessible and emotionally engaging. By depicting the events of salvation history in a visual language more relatable to a given time and place, these works offer a kind of immediacy that can draw in the viewer. They allow us to connect with Christ’s life, the saints, and biblical stories in ways that feel more tangible and emotionally resonant.

In Thomistic teaching, the soul has distinct natural faculties, including the imagination, the emotions (or passions), and the intellect. The imagination forms mental images, (called “phantasms”1) which assist us in contemplating divine truths, though it is not a direct conduit to the divine.

The emotions are movements of the soul in response to stimuli, and while they can incline us toward or away from God, they need to be properly ordered by reason and grace. The intellect, Thomas teaches, is the highest faculty, through which we grasp the highest truths about God and creation. Yet the imagination and emotions support the intellect by providing material for reflection and stirring devotion.

From this Thomistic framework, we can understand the value of naturalistic narrative art in Christian contexts. Its purpose is different from sacred icons, which are themselves sanctified objects, serving as spiritual conduits to bring the heavenly realm into the space and sanctify it. Narrative realism works within the order of nature, engaging the imagination and emotions like a type of psychological or emotional medicine or nutrition.

Properly used, narrative “historical” art operates within the natural realm, making the humanity of Christ and the saints more visible and encouraging us to identify with them. I still believe strongly that it has no place above a Christian altar. But it can be used in a more personal, devotional way, to stir our emotions, draw images on the screen of the imagination, connecting us in imagination and intellect to the biblical past, making it more “real.”

Narrative realism serves as a reminder, resonating with our human need for connection. We are not angels - we need help and nourishment for our natural faculties that art like this provides.

The Passion of the Christ: (Australian) Mel Gibson’s traditional Catholic “high” Christological theology was strongly in evidence in this film, still considered by many a work of theological value. It is well known that Gibson used paintings by Caravaggio as inspiration for his cinematography.

The Chosen and other cinematic depictions of the life of Christ

Let’s take a modern example: the television series The Chosen which has taken the online Christian world by storm, and remains controversial for Catholics and Orthodox. While it has its flaws, particularly its low Christology - unsurprising given it’s produced by Protestants (and possibly Mormons? not sure…) - I believe it and similar cinematic offerings can provide something valuable if the viewer is properly prepared.

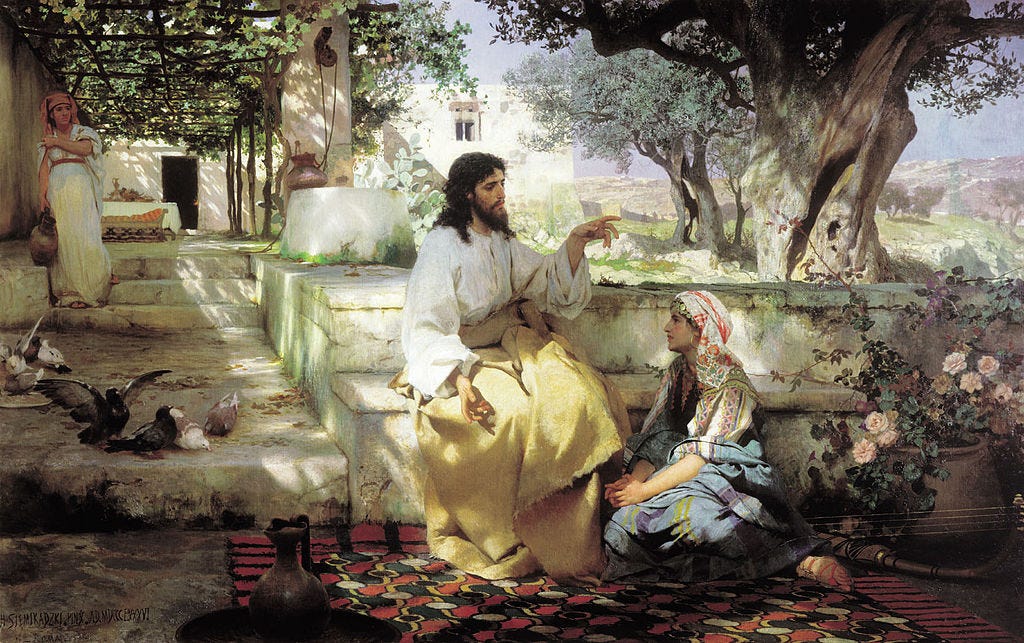

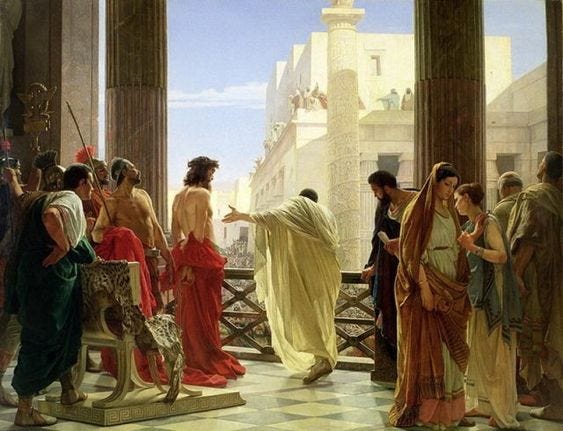

Again, although less deliberate and studied, the high Catholic Christology comes through in the 1977 film, Jesus of Nazareth by (the Italian) Franco Zeffirelli. Indeed, the presence of God is decidedly no place for the likes of me! In contrast to the Gibson film, this film’s visual style looks like the painting above by the 19th century Polish painter Henryk Semiradzki, brought to life.

Despite its theological and narrative limitations2, The Chosen provides a narrative framework for the imagination. The creators themselves often emphasize that their goal is to encourage viewers, who might feel an emotional or psychological connection to Jesus through the show, to pick up the Bible and grow closer to the real Christ in prayer. While the series doesn’t attempt to present the theological depth or spiritual mystery that sacred art or liturgy might, it does engage the imagination and emotions in a way that can serve as a first step towards deeper reflection.

Where the showrunner Dallas Jenkins often misses the mark is more in tone - the chummy, folksy, jokey tone is frequently out of place - and style than anything more serious. I know many people object to it more on cultural grounds - it’s certainly VERy American, and is clearly aimed at modern, middle class American audiences, especially in its use of modern American idiomatic dialogue.

Many of us feel disconnected from Scripture, and for us it gives familiar biblical stories a certain immediacy and liveliness that could, on a human level, encourage viewers to engage with Christ personally - which is the essence and the main purpose of prayer, after all. In this sense, like narrative “realist” art, it functions within the natural realm, offering an emotional bridge to the sacred and opening the door to possible further spiritual exploration.

Comparing these two scenes, where Jesus explains the real nature of the Kingdom of Heaven to Nicodemus - a man who wanted to believe - gives a pretty good idea of what I mean. The main differences lie in style, tone and diction, more than theology.

And of course, it can’t have hurt that Zeffirelli had access to one of the greatest 20th century actors to play Nicodemus, Sir Lawrence Olivier.

For those of us who suffer from our typical modern anxieties - overthinking, over-rationalizing, online data input overload, too much argument and constant mental noise - something like The Chosen can offer a welcome reprieve. It engages the imagination and emotions in a more direct, human way, allowing us to step out of the chaos and connect with the simplicity of the Gospel narrative. In a world filled with intellectual distractions and endless debates, this kind of storytelling can cut through the noise, giving us a moment of emotional clarity and a chance to focus on Christ in a more personal, relatable context. It’s not a substitute for direct spiritual engagement, but it can be a step towards that goal, not through argument but through story.

The Sacred Images Project is a reader-supported publication where we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. It’s my full time job, but it’s still not bringing a full time income, so I can’t yet provide all the things I want to and am planning for. You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week.

For $9/month you also get the second half of the weekly Friday Goodie Bag post, plus a weekly paywalled in-depth article on this great sacred patrimony, plus our Benedictine Book Club in the Substack Chat. There are also occasional extras like downloadable exclusive high resolution printable images, ebooks, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts.

If you would prefer to set up a recurring donation in an amount of your choice, or make a one-off contribution, you can do that at my studio blog.

This helps me a lot because the patronages through the studio blog are not subject to the 10% Substack fee. This is the site where I post photos of my own work as it develops. I have a shop there where some of my drawings and paintings are available for sale as prints, as well as some other items.

Please enjoy a browse around.

I hope you will consider taking out a paid subscription. Below the fold today we are going to examine the differences not only in style and aesthetics, but in theology, between the traditional Catholic funeral rites and those imposed on the Church since the 1960s.

Readers will remember that last week’s Friday post was cut short by the announcement of the death of a dear friend, Giancarlo Ciccia. I attended his funeral yesterday, and would like to explain to readers who might not be familiar the great value, the transporting and transcendent reality of the traditional Catholic funeral rites.

I thank everyone who prayed for my friend and for all he left behind. His loss is a great shock and will take a long time to recover from. Requiescat in Pace.

Join us below: