God bursts into the world of death; Holy Saturday in the iconographic tradition

Anastasis and Transfiguration

Let’s take just a few minutes today for a brief look at one of the most important iconographic prototypes, one that we have all seen many times but perhaps haven’t yet looked at with close attention.

On Holy Saturday, the Church falls silent. The tabernacle is empty, the altar is bare. There is no Mass. No chant. No light. In the eyes of the world, death is the close of the drama of the maddening and disruptive preacher from Galilee. His followers are nowhere to be seen, the stone is rolled over the tomb and the seal is upon it, and Roman soldiers guard it from tampering.

We wait. This strangest of all days is the still point of the world. It feels to us like nothing is happening. But the dark place of the dead is no longer dark and not silent. It is being shaken to its foundations by the triumphant shout of God Himself.

But in the Christian East, Holy Saturday is not marked by stillness, but by immense movement, cosmic and decisive, but unseen in this world.

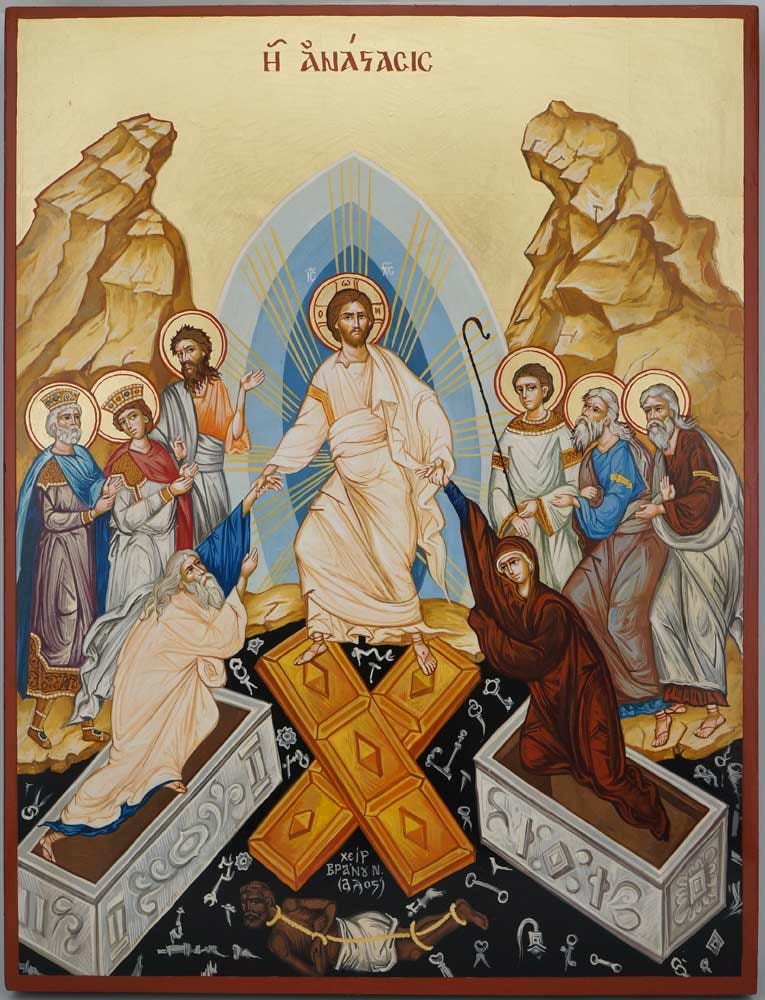

Today we turn briefly to the Anastasis, (ἀνάστασις) the icon of the Resurrection that depicts the scene we call in the west the Harrowing of Hell. It does not show the body of the dead Christ lying in the tomb. It shows what He was doing in that moment; breaking open and flinging wide the dreadful gates of the underworld, the land of the dead, trampling them down, and crushing the defeated devil under His feet.

At the Sacred Images Project we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. The publication is supported by subscriptions, so apart from plugging my shop, there is no advertising or pop-ups. It’s my full time job, and while it’s now providing me with a full time income, we are now looking at growing this into a multi-layered, multi-media project, so I can’t yet provide all the things I want to and am planning for.

You can subscribe for free to get one a week.

For $9/month you also get a second, weekly paywalled in-depth article tracing the history and meaning of our great sacred patrimony. For paid subscribers there are also extra posts with in-person explorations, exclusive photos and videos and materials like downloadable exclusive high resolution printable images. In the works are ebooks, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts.

The Anastasis, literally “a rising up” or “standing up again in Greek. It is the icon that shows us what happened beyond the view of living men after the Crucifixion. Christ has descended not as a lifeless corpse but as a radiant figure, full of divine power, bursting with the Uncreated Light, reaching down into death itself to rescue Adam, Eve and all the righteous held captive since the beginning of time. In this image, Holy Saturday is not a pause. It is an explosion.

The Anastasis is one of the most commonly repeated of all iconographic prototypes in the Eastern tradition. It is not merely a depiction of an event but a visual proclamation of victory, a theological image so central that it appears again and again in apses, narthexes, chapels and manuscripts across centuries and empires.

This is the Church’s icon showing the fulness of meaning of the Resurrection; it does not show the empty tomb or the astonished women at dawn. It shows His triumph over death at the very moment of it, His breaking down of the gates. In the eastern forms He is not just raising Adam and Eve but hauls them out of the tomb by force, gripping them by the wrist.

This is why, in the iconographic cycle, the Anastasis appears where the Western eye expects to see Easter morning. It is not the moment of return to this world, but shows us the greater mystery beneath it; the descent that makes Resurrection possible.

And that descent, so often rendered with dynamic, almost violent energy, finds a surprising visual and theological echo in the icon of the Transfiguration.

Jesus took with him Peter, James and John the brother of James, and led them up a high mountain by themselves. There he was transfigured before them. His face shone like the sun, and his clothes became as white as the light.

Matthew 17: 1-2

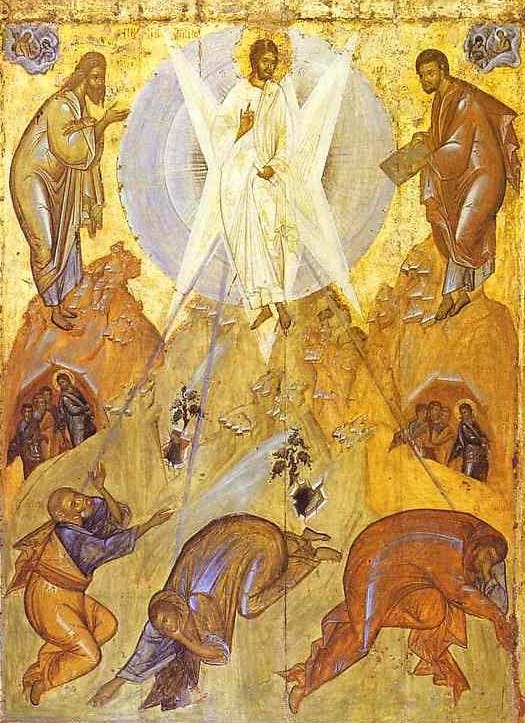

On Mount Tabor, Christ reveals His divine nature to the apostles. He stands in blinding radiance, like the sun at midday, wrapped in dazzling white, as the uncreated light explodes forth from His person. Moses and Elijah appear in the midst of that glory, with Moses, the lawgiver, standing for the Law (Torah), the foundation of the Old Covenant and Elijah, the prophet taken up to heaven in a chariot of fire, standing for the Prophets, who called Israel back to fidelity. Together, they represent the entire Old Testament, testifying to Christ as its fulfilment.

The Transfiguration is the foretaste of the glory, the reality that will be shown in Christ’s resurrected form, revealed only for a moment and only to the eyes of the three chosen disciples before His long descent into suffering and death. It is not a change in Christ, but a revelation of who He already is - a pulling back of the veil for only a moment.

While he was still speaking, a bright cloud covered them, and a voice from the cloud said, “This is my Son, whom I love; with him I am well pleased. Listen to him!”

When the disciples heard this, they fell facedown to the ground, terrified.

The disciples fall to the ground in fear, not because Christ becomes something else, but because they are given a glimpse of the divine glory hidden in His humanity. The icon of the Transfiguration is not a narrative image, but a vision, it does not seek to explain, only to show.

The visual echoes between these two icons are profound. In each, Christ is at the centre, surrounded by figures that watch, wait, or witness. In each, something lies beneath His feet that speaks of danger overcome: the black abyss of death, or the perilous, barren mountain top. In each, light descends into shadow and changes it.

As they were coming down the mountain, Jesus instructed them, “Don’t tell anyone what you have seen, until the Son of Man has been raised from the dead.”

On Holy Saturday, the Church waits. But the icons show us that this waiting is not passive. Beneath the silence of the liturgy, something has already begun. Death has been breached and vanquished. Creation is being remade. The one who once descended into the waters of the Jordan - a symbol of death - and who was transfigured like the midday sun on Tabor, has now descended into the tomb, not to remain there, but to bring the dead with Him into eternal life.

Buona Pasqua a tutti - to all my readers, supporters, and friends, may the light of the Resurrection shine into every corner of your lives. Thank you for walking through these days with me.

I"ve always been at a loss in understanding icons so this was enlightening and eye opening. The video was most helpful, also. Western art has always told stories to me because I understand it's symbology and vocabulary. I see where I need to work on learning more about the vocabulary and symbols used in icons. Thank you for educating me today--as you do so many days!

Christ is risen!