Goodie Bag for Friday Oct. 4: The Secret Power of Paper (I promise, it's not boring)

Below the fold: a walk through Old St. Peter's and New St. Paul's Outside the Walls, in Rome

The other day in the comments someone mentioned that, even though they’d heard it mentioned forever, they’d never really known or thought about what parchment is in medieval book making. It got me thinking a little; what really was the effect of the paper book printing industry on our culture?

It’s easy to take paper for granted in our age of endless reams of cheap, mass-produced sheets. But there was a time when paper was a high end luxury item, a precious resource used only for the most important documents and works of art. The town of Fabriano in Le Marche, in central Italy, was at the heart of Europe’s paper production, and even today, it still holds an important place in the history of this humble, almost unnoticeable, yet epoch-making material.

It might sound a bit of a technical side track, but the development of paper making as an industry, for use in the new mechanical printing techniques, represents a crucial moment in our history. The printing press gets all the attention, especially when talking about its influence on development of early modern period1 politics, technology and learning in 16th century Europe, but it’s funny how the question never seems to arise; what were they printing on? Because it wasn’t parchment.

Then I started thinking about how the switch from parchment and hand made books to paper and printed books altered something much more fundamental about western Christian culture than just the rapid dissemination of information and ideas. It altered our perception of how we move through time. It was the first stage in the speeding up of the world.

What’s parchment?

Most of the videos about the incredibly laborious process of making parchment make the same mistake, calling it “an old kind of paper”. This is because 500 years later, we have almost forgotten that there ever was anything else to write on. But parchment isn’t paper, because “paper” doesn’t just mean “something flat that you write on.”2 Paper refers to the stuff you get when you create a writing surface using the pulp of vegetable fibres, like wood or cotton, papyrus or bamboo.

Parchment is something else.

And it’s kind of gross if I’m being honest. Imagine going through all this, and of course, raising the animals that provide the raw materials, in sufficient volume to support the publishing industry of the 17th or 18th century.

Paper and Permanence: From Fabriano to the Printing Press

The watercolourists among us will know the brand name of artists’ paper, Fabriano, but they might not be aware that it is actually the name of the town that was the heart of Europe’s paper making industry through the middle ages. Fabriano’s paper production dates to the 13th century when the technique of creating vegetable fibre pulp and collecting it in a frame to become paper, was brought from Asia to Europe - like so many other luxury goods - along the Silk Road3.

Despite paper’s eventual widespread use, in the 13th century, it was still very much a luxury item. Paper was easier and cheaper to produce than parchment or vellum, but it wasn’t yet something used for everyday writing.

Parchment remained the preferred material for any document or book that needed to last, particularly in religious and legal contexts, because it was far more durable.

But for the sheer volume that was to be required for the printing press, paper was the only possibility. And it was from this small, now-obscure, town that paper-making techniques were refined for European uses, and spread across the continent.

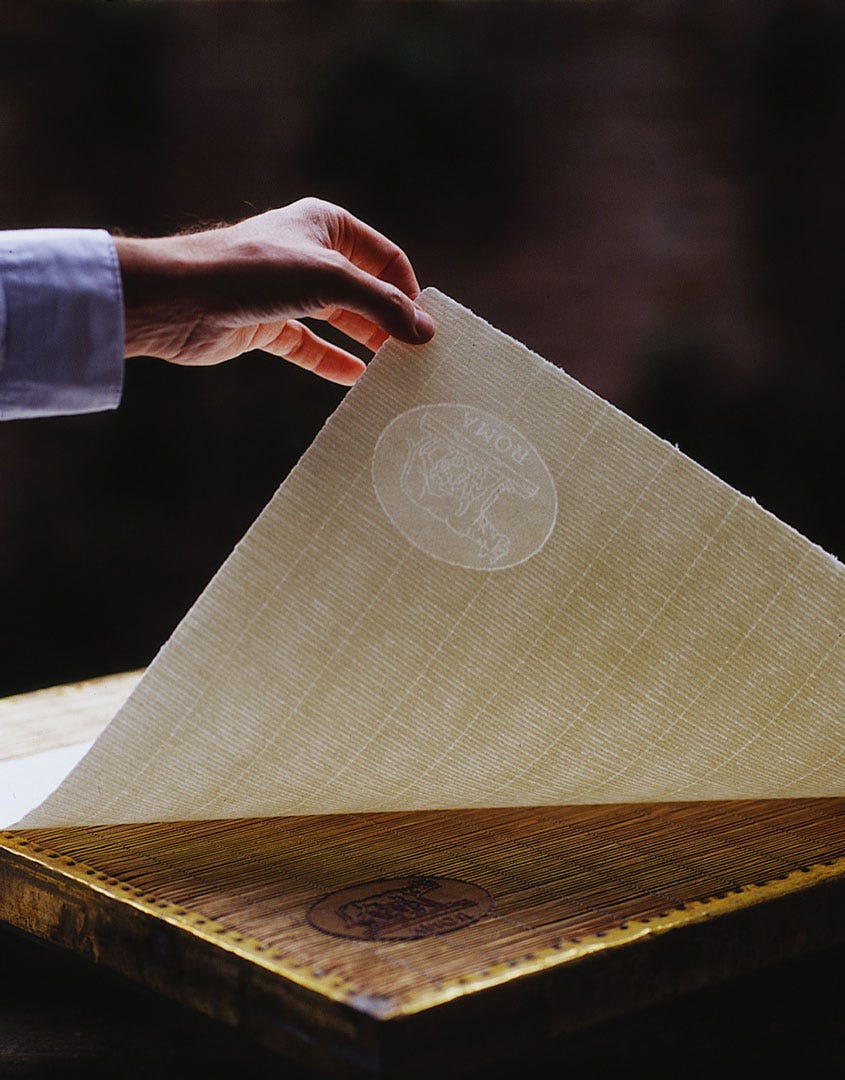

Fabriano lays claim to the invention of several techniques that made paper easier to produce and more marketable, including the watermark. The industry that developed there still thrives today, and it’s not uncommon to find handmade paper of the highest professional artist-grade, produced there in much the same way as it was centuries ago.

Artists tend to be paper-nerds, and I am probably inordinately excited by the plan to go to Fabriano to visit the paper museum.

And I really do want to go there to buy some more paper, and to check out one of Europe’s last fully functioning water-powered medieval hammer mills. This was used to pound the cotton rags into a fine pulp. It was this piece of technology, not the printing press, that started us on the road to industrialisation and fast manufacturing. Before the hammer mill was used to pound cotton rags to pulp, the process was slow and labour intensive. The mill made the final product more available and cheaper.

I buy handmade paper from Fabriano myself - beautiful, thick velvety sheets made from cotton fibre. (Who’d have wood pulp?) Vito is a true craftsman who makes his paper using traditional methods. He comes to the medieval festival in Narni each summer, setting up a stall where I’m always eager to purchase a few sheets for my own work.

His watercolour paper - sized using the traditional animal-skin gelatine - is a joy to use, with a texture and durability that reminds me of how, in a world where paper was rare, the material itself became part of the artistry. It always feels like an event, an important part of my professional life, when Vito comes to town for the festa market.

The Chinese weren’t the only ancient people who invented paper.

When I was a kid, I watched a documentary about ancient Egypt, and was fascinated by the fact that the Egyptians invented a unique kind of paper made from papyrus, a reed that grew abundantly along the banks of the Nile. Papyrus scrolls and documents are remarkably durable, and many survive to our day in museums and archival libraries.

The Printing Press and the Paper Revolution

Despite Fabriano’s innovations, paper didn’t become a staple of everyday life until the invention of the printing press in the 15th century. But without paper, the printing press would never have got off the ground; parchment was simply too expensive and slow to produce in the quantities needed for mass printing.

The printing press transformed paper into an economically viable product, and of course, created immense demand. And the combination of these technologies allowed books and pamphlets to be produced quickly and in previously unimaginable numbers.

Paper became the material that fuelled the total revolution that would lead to the modern world; the spread of knowledge, political and philosophical ideas (not to mention heresies), and finally revolutions that changed the world forever. Martin Luther’s 95 Theses wasn’t read only by the few gathering around the church door that day. His ideas were endlessly reproduced in paper pamphlets that were easy to distribute far and wide.

The Loss of Permanence: Paper and the Modern World

But this shift also changed how we think about time and permanence. Before paper and the printing press, books were painstakingly made by hand, the combined efforts of many highly specialised craftsmen. It hardly mattered how long they would take to make; books were intended to last for centuries, and of course many of them did. Books were as much works of art, and often as important to Christian culture as icons.

The long hours spent creating a manuscript reflected the idea that its content was meant to endure for ages. Men of the medieval world thought about the future with a serene and supremely unhurried, un-anxious mind; they thought about time itself in a way that we have difficulty articulating now in our speeded up, factory-time, anxiety-riddled world of constant instability, permanent change.

With the advent of paper and the printing press came a massive cultural shift in the way we think and perceive the world, and time within it. Books could be printed quickly on cheap paper, and the ideas in them could spread just as rapidly. They were no longer seen as cultural artifacts meant to last a thousand years; they became something closer to entertainment, a way to pass the time with the latest Bright Ideas spread around like popcorn in a theatre.

The very speed of their creation and dissemination often meant the ideas in them were no longer seen as eternal or indeed even meaningful - all ideas, all philosophies, all ways of thinking about life were now subject to change that was as rapid as the press could work; and burnt out as quickly as a summer grass fire.

Paper’s inherent fragility and impermanence was a perfect medium for the impermanence and ultimately the chronic and exhausting philosophical and material instability of the modern world.

Maybe we should take a lesson from Japan - Wabi-Sabi and painting on paper

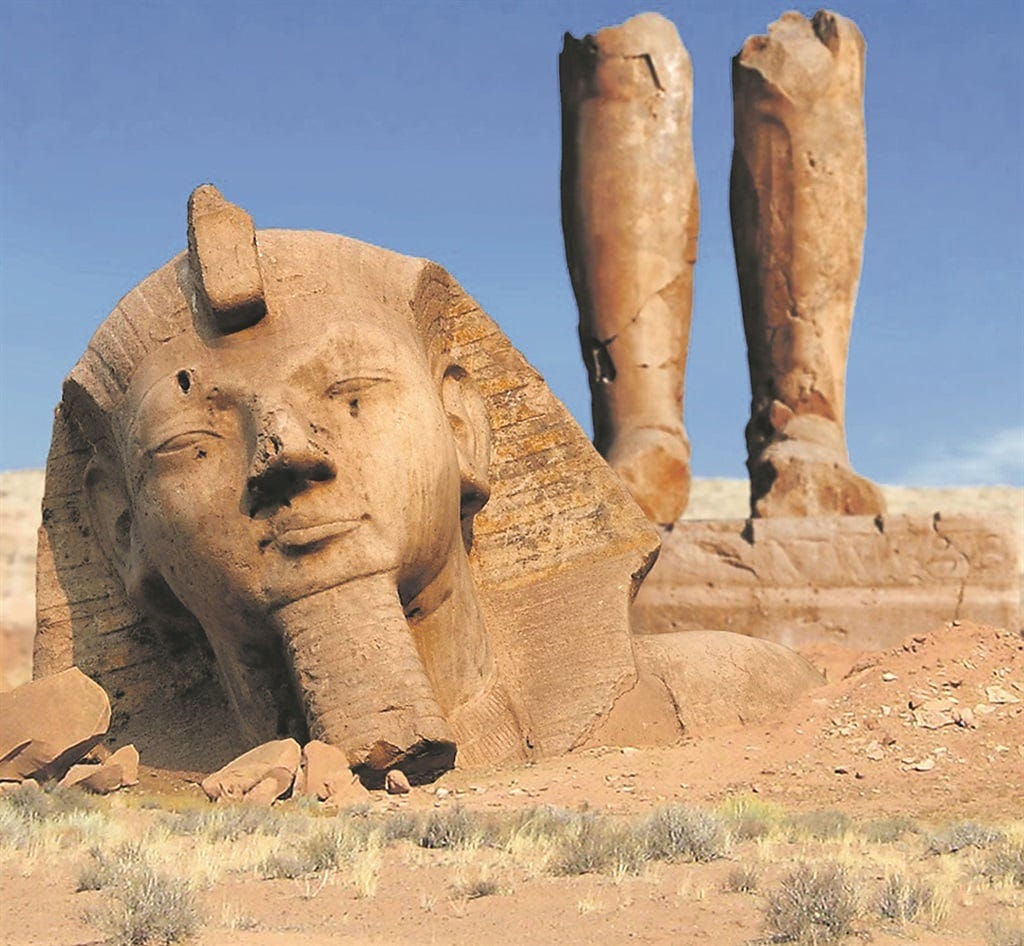

We who inherited our cultures from the ancient Near East are obsessed with trying to create permanence and lastingness in this life, leaving behind pyramids and ziggurats, stone temples and the ruins of massive cities wherever we went. And how does that invariably work out?

“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone / stand in the desert / Near them, on the sand / Half sunk a shattered visage lies … Nothing beside remains./ Round the decay / of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare / the lone and level sands stretch far away.”

St. Benedict in his Rule exhorted the monk to “keep death daily before his eyes,” to be aware constantly of the impermanence of this life and fix his attention on the next. His great abbey of Monte Cassino was destroyed by invading Lombards scarcely 30 years after his death; it has been destroyed and rebuilt a total of 4 times, the most recent in the 20th century. Monastics know all about the impermanence of this life, and at the same time they are masters of the long-term planning - planning for the ages - that seems to be a lost mental characteristic almost everywhere else.

How to acquire this excellent balance?

Our western aspirations to grand material permanence contrast sharply with the way paper was, and still is, used for art in Japan. There, paper has always been an essential medium for art, but they do not share our desperate focus on permanence - something they understand, in their shaking country, is simply not a part of life in this world.

Japanese painting is done mainly on paper (silk panels are also sometimes used) instead of more lasting materials like the gessoed wood panels used in the European middle ages, embracing the impermanence and changeability of the material world. Japanese artists have long used paper in ways that celebrate its fragility, creating works of art that are meant to reflect the ephemeralness of life itself.

Chen Yiching is a Taiwanese painter in the Japanese “Nihonga” style who works in Paris.

She’s speaking in French, but click the subtitles and choose your language for automatic translation.

The Sacred Images Project is a reader-supported publication where we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. It’s my full time job, but it’s still not bringing a full time income, so I can’t yet provide all the things I want to and am planning for. You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week.

For $9/month you also get the second half of the weekly Friday Goodie Bag post, plus a weekly paywalled in-depth article on this great sacred patrimony. There are also occasional extras like downloadable exclusive high resolution printable images, ebooks, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts.

If you would prefer to set up a recurring donation in an amount of your choice, or make a one-off contribution, you can do that at my studio blog.

This helps me a lot because the patronages through the studio blog are not subject to the 10% Substack fee. This is the site where I post photos of my own work as it develops. I have a shop there where some of my drawings and paintings are available for sale as prints, as well as some other items.

Please enjoy a browse around.

In the paid section of today’s post I have a set of photos from a friend who recently made a pilgrimage to the great Roman Basilica of St. Paul’s Outside the Walls, that was destroyed by a terrible fire in the early 19th century, and rebuilt.

I would like to compare it with some fascinating old paintings and some recent computer animations reconstructing Old St. Peter’s Basilica, the church built by Constantine and replaced by the current Baroque basilica. St. Paul’s and Old St. Peter’s were two of the great Imperial-era Christian basilicas, of which only 5 survive into our time.

Subscribe to join us: