Goodie Bag Sept 20: Carolingian or What? quiz answers and a look at some monastic success stories

And a prayer request

Quiz answers!

From all the way back to September 7th - “Carolingian, or what?”

Again, everyone did really well, especially considering that this is a new topic, and frankly Carolingian can be a little hard to nail down, stylistically. The secret is to look for very lively illustrative style for the figures, plenty of Roman stuff (swirly acanthus leaves) and strong elements that look like they come from Ireland, “Celtic” knotwork and interlacing. If you’ve got all three: that’s Carolingian.

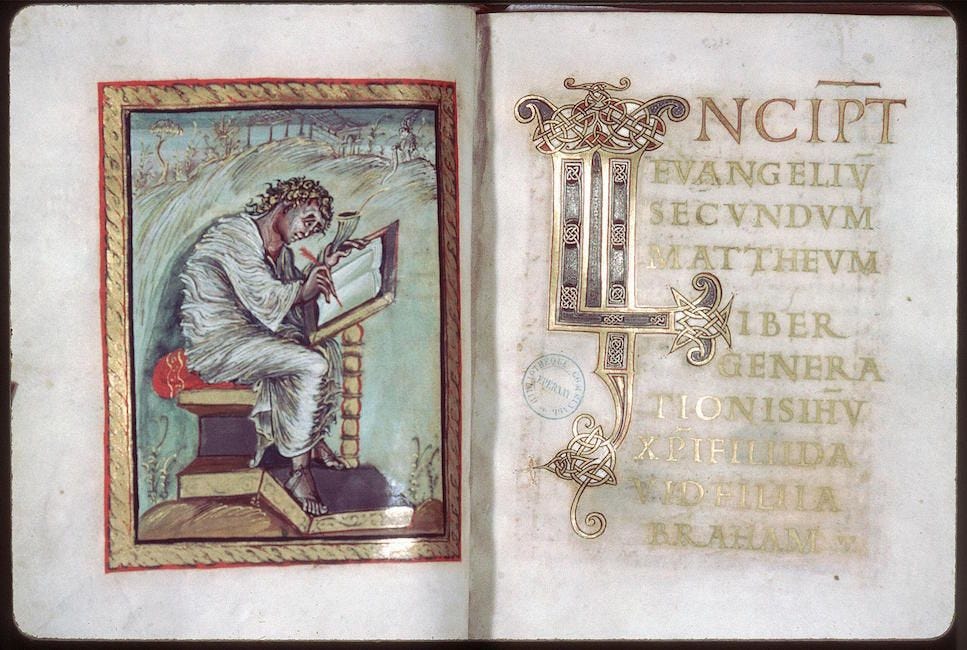

Ebbo Gospels

Ebbo Gospels: a Carolingian illuminated manuscript, created around 816-835 AD at the Abbey of Hautvillers under the direction of Archbishop Ebbo of Reims. It stands out for its dynamic, expressive style, which merges traditional classical motifs with vibrant, energetic lines that are reminiscent of Celtic and Insular art. The figures in the Ebbo Gospels are often shown with exaggerated, almost frenetic expressions and movements, giving the scenes a sense of urgency and emotional depth uncommon in earlier Carolingian works.

The Celtic influence can be seen in the intricate and mathematically precise interlacing patterns in the “Incipit” capital, as well as the use of bright, vivid colours and swirling forms, drawing on the legacy of earlier Irish and Anglo-Saxon manuscript traditions. This blend of styles of the Ebbo Gospels reflects the cosmopolitan reach of the Carolingian Renaissance.

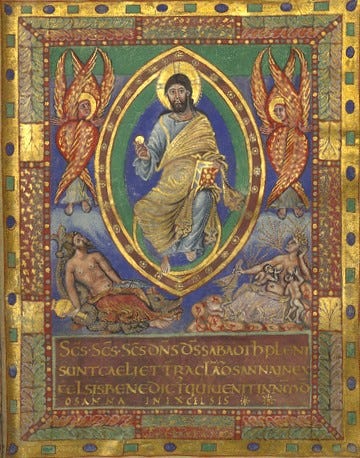

Codex Aureum of St. Emmeram

The Codex Aureum of St. Emmeram, created in 870 AD at the court of Charles the Bald, is one of the most lavish and opulent manuscripts of the Carolingian period. Commissioned for presentation to the Abbey of St. Emmeram in Regensburg, the codex is notable for its extensive use of gold leaf and gold ink, richly coloured illuminations, and the exquisite refinement of its miniature art.

The manuscript exemplifies the Carolingian revival of classical artistic traditions, with figures that exhibit a calm, regal dignity - using Byzantine both stylistic canons and Roman realism - and an emphasis on symmetry and order. However, Celtic and Insular artistic elements subtly appear in the intricate and lavish decorative borders, geometric patterns, and stylized animal motifs. These details show how the Carolingian art, while deeply inspired by Roman models, also absorbed the distinctive visual language of the northern European Christian world, creating a sophisticated synthesis of artistic styles.

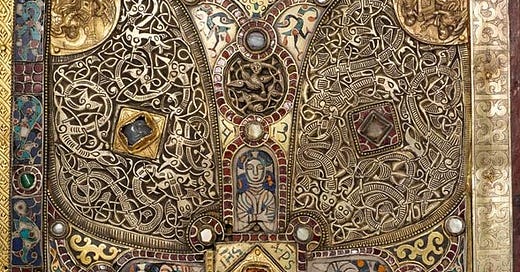

Lindau Gospels

The back cover of the Lindau Gospels is an extraordinary example of Carolingian metalwork. Made of gold, silver, and studded with jewels, the back cover is adorned with intricate repoussé work—where figures and patterns are raised from the metal surface. It’s really easy to see how half of you guessed that this is Hiberno-Saxon or Insular/Irish, and the historians posit that it was indeed made on the islands or by an imported Insular metalworker.

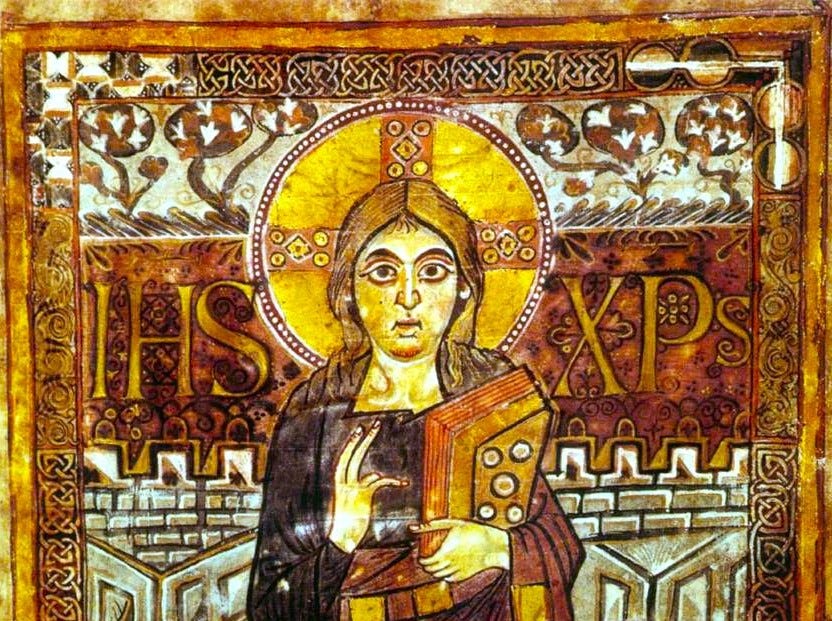

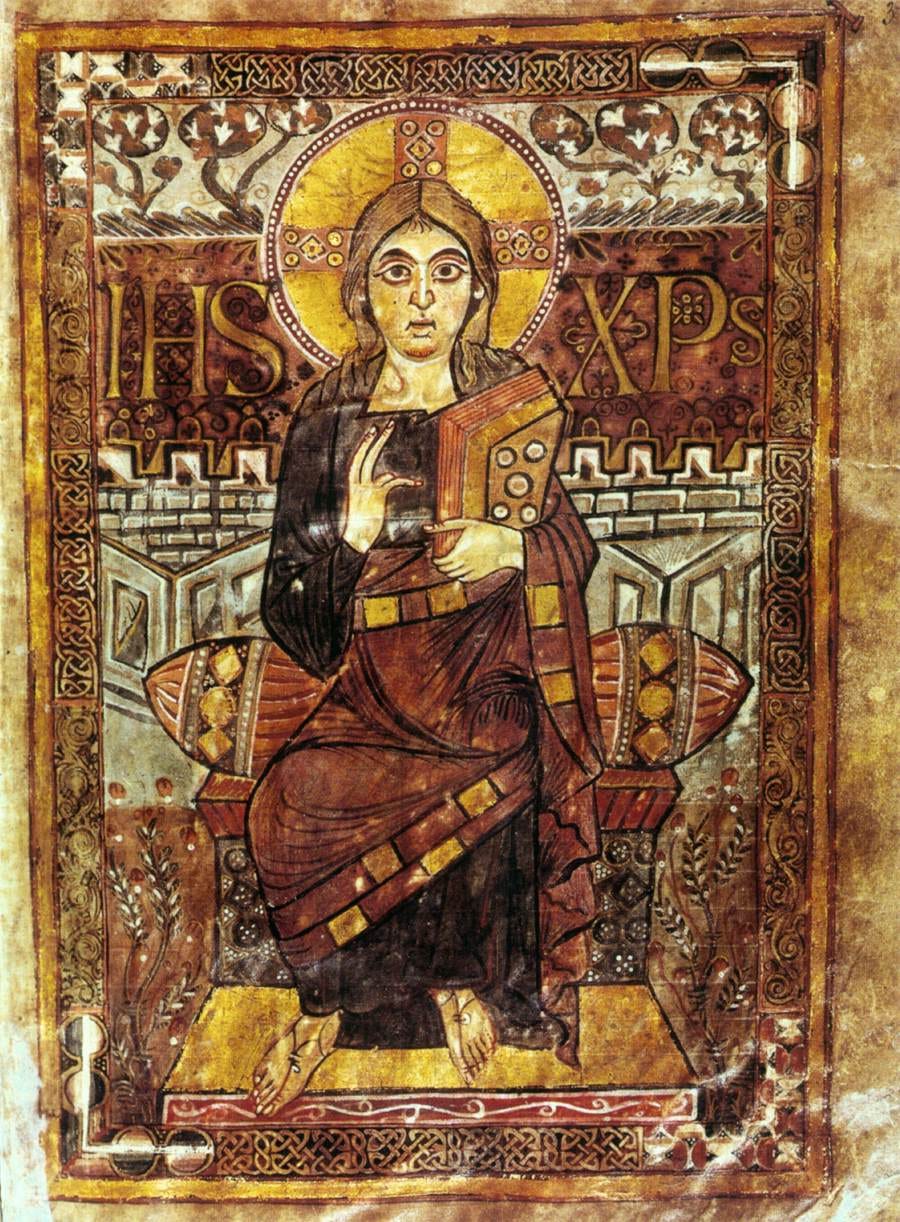

Godescalc Evangelistary

Commissioned by Charlemagne himself, and completed in 783 AD, this manuscript is one of the earliest and most important of the Carolingian Renaissance. Created by the scribe Godescalc, it represents a return to classical artistic forms while also reflecting early medieval Christian symbolism and western European decorative styles. The illuminations feature vivid colours, intricate geometric patterns, and ornate the framing typical of the style. Classical influences are evident in the depiction of human figures, which are stylized yet exhibit a sense of proportion and grace, reminiscent of late Roman art. Intricate interlace patterns and highly decorative borders, echo the Celtic and Insular manuscript traditions.

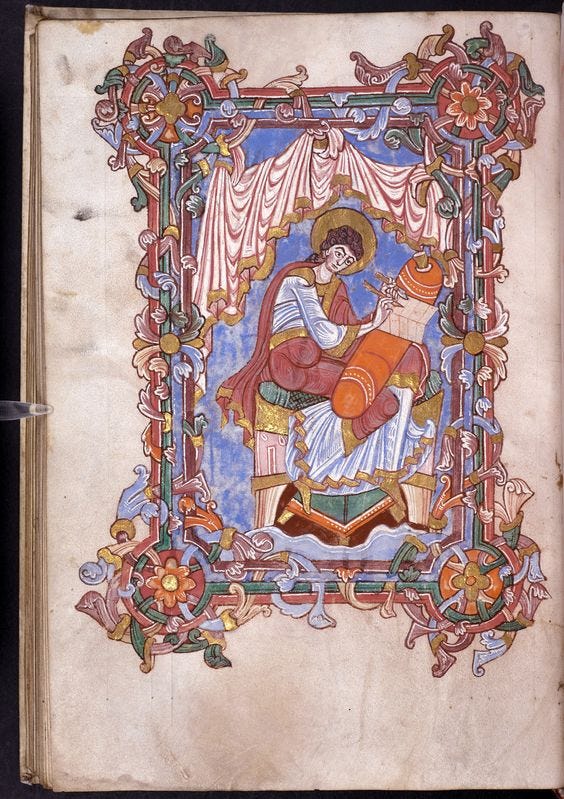

St. Luke portrait page; Preaux Gospels

Unlike earlier Carolingian examples, which used the figural proportions of classical naturalism, the Préaux Gospels embraces the bold, stylized swirling style typical of Romanesque art. The figures are less concerned with realism and more focused on symbolic representation, with elongated bodies, exaggerated facial expressions, and sharp, angular “damp fold” drapery.

The illuminators used bright, contrasting colours - deep reds, golds, and blues - to create a sense of otherworldly brilliance, often outlined with thick black or dark lines that give the compositions a graphic, almost mosaic-like quality. The imagery is dense and tightly arranged, with figures and decorative elements often filling every available space, leaving little room for an illusion of spatial depth. The decorative borders feature intricate patterns and motifs, though now adapted to the more rigid, formalized aesthetic of the Romanesque period.

Bonus Round: Santa Pudenziana

You’ll remember back in February when we visited the lovely little Romanesque church in Lugnano in Teverina and talked about the features of early Christian church architecture. The structure over the main altar - that the Italians call a baldachino - is properly called a “ciborium”.

I’ll admit to having a little fun with the other options, only one of which wasn’t made up. It turns out that Greek is fun to play around with.

The Sacred Images Project is a reader-supported publication where we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. It’s my full time job, but it’s still not bringing a full time income, so I can’t yet provide all the things I want to and am planning for. You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week.

For $9/month you also get the second half of the weekly Friday Goodie Bag post, plus a weekly paywalled in-depth article on this great sacred patrimony, plus our Benedictine Book Club in the Substack Chat. There are also occasional extras like downloadable exclusive high resolution printable images, ebooks, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts.

If you would prefer to set up a recurring donation in an amount of your choice, or make a one-off contribution, you can do that at my studio blog.

This helps me a lot because the patronages through the studio blog are not subject to the 10% Substack fee. This is the site where I post photos of my own work as it develops. I have a shop there where some of my drawings and paintings are available for sale as prints, as well as some other items.

Please enjoy a browse around.

The “vocation crisis” is a myth: one western and two eastern monasteries

We’ve all heard it by now: the Western Church has been confronted with an unprecedented “vocations crisis,” the number of men and women entering the priesthood and religious life has plummeted. It’s become old hat; I’m sure I don’t need to post the graphs. We all know what it looks like: a little guy with a blue pencil starts in 1900 and climbs an impossibly steep mountain until he hits a precipitous cliff exactly in 1965, and then falls right off. And this is in every category you can name, except perhaps, “numbers of Catholics who have given up going to Mass every week.” The news is almost uniformly dismal, and that goes double for women’s religious life that seems to be shutting down from sheer lack of interest.

Since we are nearing the end, the causes get talked about less and less often, but it’s notable that even now almost no one is willing to admit to having made bad choices. The collapse is usually attributed to a variety of external social factors - rising secularism, the morally deadening effect of the modern culture of comfort-and-convenience... “Young people just can’t commit…” At this late stage, there seems little point in going over it.

In contrast to this trend, however, some communities have experienced a remarkable revival, a contrast hardly anyone in the institution of the western Church is willing to talk about. But it remains irrefutable - and infuriating in many corners - that orders that have retained the traditional Christian purposes of religious life - prayer, sacrifice, devotion to the traditional liturgy and the communal life - are not only surviving but flourishing. These communities, crucially, have largely resisted the lure of political and ideological fads, embracing and focusing on the ancient tenets of monasticism. These are are attracting comparative armies of young - and often not so young - women seeking a deeper spiritual life and a return to the roots of Christian devotion.

The Benedictine Abbey of Gower has had so many vocations that they've opened not one, but two daughter houses. This little abbey in rural Missouri has grown so fast their biggest problem was needing more room, and now they’ve expanded their reach across the Atlantic, opening a new community in England. It’s a remarkable achievement, and a sure sign that their traditional way of life is striking a chord not only in America but internationally. The message is clear—when religious life stays true to its roots, it can flourish even in the most unexpected places.

St. Elizabeth’s convent, Minsk

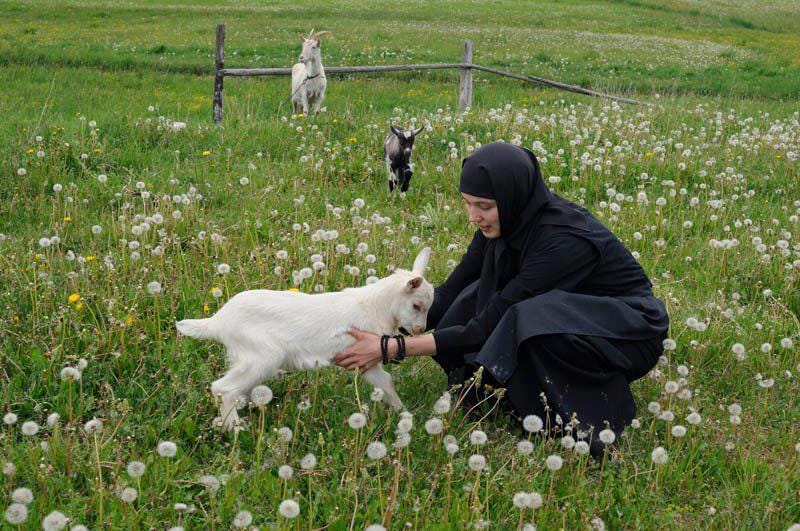

But it's not just happening in places like Missouri. In the East, St. Elizabeth’s Orthodox Convent near Minsk has been quietly experiencing its own boom. Founded in 1999, the convent started with just a handful of sisters and a mission to serve the most vulnerable in their community.

These stories are incredibly moving of the people the sisters care for, former prisoners, drug addicts, alcoholics and homeless, men and women who had no other place to go in the world.

They have two “rehabilitation” farms, one for men and one for women, run an orphanage for mentally disabled children and an animal sanctuary.

This is where the rescued and rehabilitated horses and dogs are put to work helping children with autism and developmental problems.

The horse work is done by a hermit nun who came to the convent with nowhere else to go after overcoming drug addiction and being diagnosed with a terminal illness.

They have an icon workshop but the pressure of orders became so great they expanded it into a school of iconography to train more painters.

They have herbal, ceramics, metalwork workshops and a wax works where they make candles, from wax that comes from bees kept at the men’s farm.

In only two decades they’ve grown into a thriving spiritual and charitable hub, with over a hundred nuns and over 800 associates, including a large contingent of lay sisters1.

Like Gower2, St. Elizabeth’s has stuck to the ancient rhythms of monastic life—prayer, work, and service. They've held onto their traditional liturgical practices and resisted the distractions of modern ideological trends. And people have noticed. Not only have they drawn in more vocations, but they've also become a crucial part of the local community, providing spiritual and material support. It’s another clear case of a traditional order, rooted in its founding purpose, flourishing in the face of an otherwise dismal trend.

Orthodox vs. Western monasticism

In Orthodox and Byzantine Catholic monastic life, there’s a key difference from the West—there aren’t distinct “orders” like the Benedictines, Dominicans, or Franciscans. Instead, eastern monasticism is unified under the same basic rule for all monks and nuns, with a focus on personal asceticism, prayer, and communal living.

While each monastery may have its own local customs, they all share the same foundational practices, such as the strict adherence to the liturgical cycle. Eastern monastic life is more about continuity across regions and over time, emphasizing a single, cohesive path to spiritual growth based on the work of the early Church Fathers.

Gradac in Serbia

The community of Orthodox nuns at the ancient Gradac Monastery in Serbia is a more recent revival of monastic life. Gradac, founded in the 13th century by Queen Helen of Anjou, was a flourishing spiritual centre in medieval Serbia before facing centuries of neglect and decay. The monastery, like many others in the region, suffered during the Ottoman era and was largely ruined and abandoned for a long time.

In recent years, however, the monastery has been restored, and a new community of a dozen Orthodox nuns has taken residence. These nuns have committed themselves to restoring not only the physical monastery but also its spiritual life, reviving ancient monastic traditions, engaging in regular liturgical services and supporting themselves by painting icons.

The community has become a small but vibrant hub of monastic life, drawing on the deep spiritual roots of the region while attracting pilgrims and visitors who come to experience the monastery’s peaceful environment. Though still small, the community at Gradac reflects a broader trend of renewed interest in traditional monasticism within the Orthodox world, especially in historical sites like this one.

The nuns at Gradac Monastery have gained recognition for their beautiful and meticulous iconography work, which is deeply rooted in the traditional methods of Orthodox icon painting. Like many Orthodox monastic communities, the sisters at Gradac embrace iconography as not merely an art form but a sacred craft that combines prayer and technical skill.

In an interview with AFP in 2011, the superior told the story. When she was Jasna Topolski, already a famous artist who had graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Belgrade, she arrived at this 13th-century monastery. Today, she is Efimija, the mother superior.

"(As an artist) I thought that art would allow me to find the truth, to resolve the mystery of death, but I had found no answer," the 46-year-old told AFP. “I started looking elsewhere and realised that the church could provide me with the complete answer" to the big questions about life.

She was soon followed by several other young women, fellow fine arts students who were equally torn between religion and art.

"Some among them were considering joining the order but were not sure how their artistic sensibility could adjust to monastic life. So when they saw me here, they decided to try. They liked it, so they stayed," Efimija said.

That's what happened to Sister Magdalina, Mother Efimija's closest aide in Gradac. In the convent workshop, she teaches other nuns the art of icon painting.

"The more we paint, the more they (icons) seem to be elusive ...We can never say 'I mastered the technique of painting icons'," Sister Magdalina said.

"I believe that great artists are all believers, even though they are not aware of that sometimes. I don't believe that we can reach such (artistic) depth if there is no (divine) light within ourselves," she added.

Please pray for my friend

I’m going to have to stop here today, without a separate paid section. I’m afraid I’ve had a bit of a shock today and am going to break protocol a bit and ask for prayers. This afternoon I had news that a very dear friend has died.

I’d known him since our Toronto days at the Oratory when he very ill-advisedly agreed to tutor me in Latin. I never made much progress in the language, but we became fast friends. He moved to Rome and a few years later with considerable encouragement from him I moved over too.

Please pray for my friend Giancarlo Ciccia, who passed away after a prolonged illness.

Here is a little obituary by our mutual friend Gregory diPippo at New Liturgical Movement.

Of your charity, please pray for the repose of a friend, Mr Giancarlo Ciccia, who passed away in Rome earlier today as the result of a long-term illness. For many years, he served as one of the masters of ceremonies and sacristans at Santissima Trinità dei Pellegrini, the FSSP parish in Rome; the reputation which that church has long enjoyed for the superb quality of its liturgies is due in no small measure to his constant hard work and diligence. He was very much involved in the revival of the church’s confraternity, whose members helped greatly with taking care of him during his illness; he was also an extremely talented Latin scholar, and had taught Latin at the Dominican university in Rome, the Angelicum.

Closer to our oblates or tertiaries, they are women who are associated with the community and receive spiritual direction, but live outside the monastery. Some are single and some married. They are given a modified religious habit to wear over their street clothes when they are engaging in their various ministries.

In the Benedictine world it’s normal to refer to a particular house by it’s place name, rather than its formal name. Gower, Clear Creek, Le Barroux, Norcia, etc.

Thank you for sharing the encouraging bits about the traditional monasteries. I will pray for your friend.

Our prayers and our condolences at the passing of your friend and our mutual acquaintance, John Carlo. RIP.