How to Reboot Monastic Life and save Christendom

Towering Figures of the Early Middle Ages: St. Odo of Cluny

We’re rejoining our “Towering Figures of the Early Middle Ages” series today, and once again I’ve discovered that I completely underestimated how fascinating and critically important this moment of history really is. I had imagined I could sweep three of the great Cluniac abbots into a single post; silly me. You can’t skip lightly past a figure like Odo of Cluny with a set of biographical bullet points, given the momentous changes he helped set in motion.

Odo’s great edifice was spiritual not physical

Looking closely at his life has become an unexpectedly absorbing study in how a Christian society can pull itself out of a “dark age” by returning to foundational Christian principles, by going back to an earlier point of divergence, correcting course and restarting. And all this feels far more immediately relevant to our own increasingly chaotic times than I had anticipated. In Odo of Cluny, we find someone who, across a distance of more than a thousand years, offers guidance for how renewal might look again.

Coming after this, we’ll begin tracing the extraordinarily far-reaching effects that the Cluniac reform would have under Odo’s successors in every aspect of European cultural life. What began as a fragile effort to recover the true Benedictine life in a small group of obscure monasteries in France, grew with extraordinary speed into an colossal cultural, political and artistic engine of renewal across Christian Europe. Under Mayeul and Odilo, Cluny drew hundreds of monasteries into its reforming orbit, including venerable houses like Farfa, Subiaco and even Monte Cassino itself. These ended up forming a kind of pan-European spiritual commonwealth anchored in the purpose of monastic life: pursuit of union with God under St. Benedict’s Rule, using the vehicle of the reverent chanting of the Divine Office, the Opus Dei.

This reform was not only moral and liturgical: the unity the Cluniac reform ignited an artistic and architectural awakening as well. As Cluniac monastic life stabilised and expanded, the desire to express the splendour of the western liturgy in stone, sculpture, fresco and illumination took hold, launching the Romanesque style that would soon transform Europe’s visual imagination.

Finally we will arrive at the giantest monastic giant of them all, St. Hugh of Cluny, under whom this movement reached its astonishing height. Abbot Hugh oversaw the construction of Cluny III, the colossal monastic basilica whose staggering scale made it the largest church in European Christendom for nearly five centuries, until the re-building of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome in the 16th century. At its height, Cluny was home to an astounding 10,000 monks.

Odo is not famous for having built a church, but for re-creating Benedictine monastic life itself, understanding that no grand edifice of stone could ever be an accomplishment without the life of devotion lived within its walls. His concern was creating the foundation that had to come before any stone was laid: the restoration of the Divine Office to its proper centrality, the reordering of time around prayer, the renewal of discipline, charity and communal purpose. Cluny would one day rise into one of the most impressive physical sacred complexes in Europe, but the possibility of such splendour was born of Odo’s insistence that monks must become monks again; the Rule must be lived in its fullness before anything lasting could be built upon it.

But we’re not there yet.

Last time, we talked a little about the dismal political and ecclesiastical situation in Western Europe at the moment of the founding of Cluny by Duke William of Aquitaine, the early 10th century.

It might seem strange that we could relate to the difficulties of the early 10th century from such a great distance in time. But looking closer, we might find it has a general ring of familiarity to us today in our disturbing, apparently epoch-ending times.

By 900 AD, the Carolingian order that had generated hope for renewal and stability a hundred years before had completely unravelled. Europe was surrounded by threats and the countryside was carved into petty fiefdoms held by men who called themselves lords but behaved like raiders.

Little relief was offered from bishops who were entangled in the same political battles and who often held their sees as hereditary property. Monasteries were overseen by absent superiors chosen externally for political connections, and routinely stripped of land, treasure and even monks when a warlord needed provisions. The core principle of Benedictine life, stability and the focus on prayer, had ceased to be the default.

We’ve discussed how William’s foundation charter of 910, backed by the papacy, was a structural revolt against the disintegration of European Christian civilisation, a re-anchoring of principles that had been overwhelmed by apparently insoluble circumstances. The decision to remove Cluny from all secular and episcopal control and make it accountable only to the Pope was unprecedented, and an astonishingly prescient move for long-term renewal. Cluny could not be financially milked or handed down as a family asset, nor commandeered by a passing army, nor bent to the political expedience of local nobility.

It was in this unique historical pocket of opportunity we find St. Odo the Abbot who understood that a monastery released from feudal interference could still decay from within, and set about building its spiritual foundations. Crucially, Odo insisted that the daily recitation of the Divine Office must be the heart of the community, the absolute centre and purpose around which everything else revolved. Cluny was to revive the concept that the Rule of St. Benedict must be taken in its entirety as a daily map for reconstructing the monastic life.

In today’s post for all subscribers, we’ll carry on our “Towering Figures” series with a look at how the remarkable Abbot Odo carried Cluny from its fragile beginnings to the start of its pan-European spiritual influence, opening the way for it to become a Benedictine empire-within-an-empire. It was this spiritual renewal that laid the intellectual and liturgical foundations for the great flourishing of Christian art in medieval Europe.

If you’ve been reading along and finding this work worthwhile, I hope you’ll consider taking out a paid subscription. The Sacred Images Project now forms the heart of the Ars Sacra Cultural Association, and paid subscriptions are what allow me to keep researching, writing, and producing the in-depth studies, and even in-person investigations.

The Sacred Images Project offers two posts a week — one free and one for paid subscribers — each exploring the rich history, theology, and beauty of Christian sacred art from the 4th to the early 15th century.

A paid subscription is only $9/month and unlocks:

- An in-depth, paywalled article every week

- Full access to the complete archives

- Joining the discussion in the comments

- High‑resolution images and other downloadable materials.

If you’d prefer to set up a monthly donation in an amount of your choice, or make a one-off donation to the work, you can do that at the studio blog here:

If you set up a recurring monthly donation above $9/month, I will manually add you to the complimentary subscription list here for a year, which means you’ll have all the benefits of a paid subscription.

I hope you’ll enjoy a browse in The Gilded Corner Market, our online shop that provides a way to bring the world of sacred art into your daily life. Most readers live far from the frescos and illuminated manuscripts we explore here, so the shop offers a curated selection of prints, gifts and small objects inspired by the artworks we study together.

There’s still plenty of time for orders to arrive for Christmas.

Like these tree ornaments:

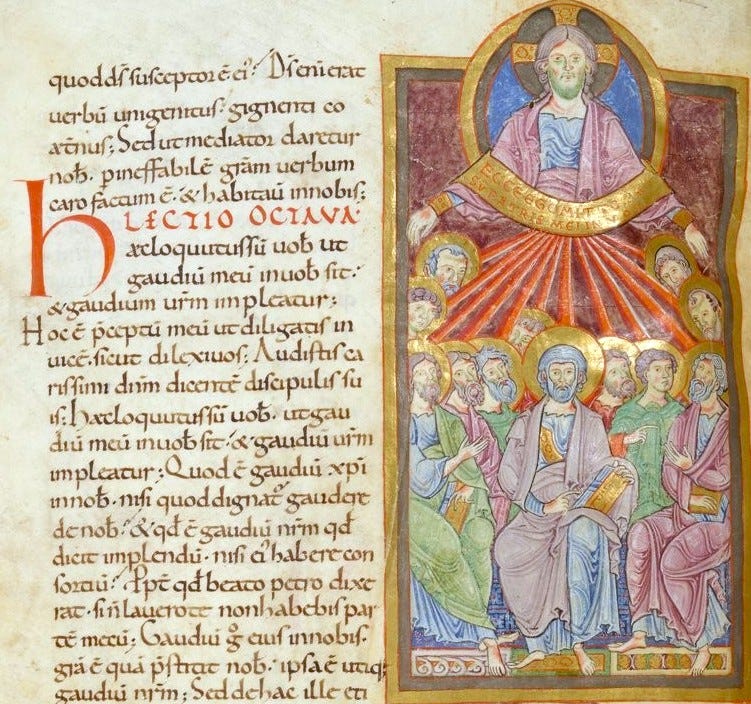

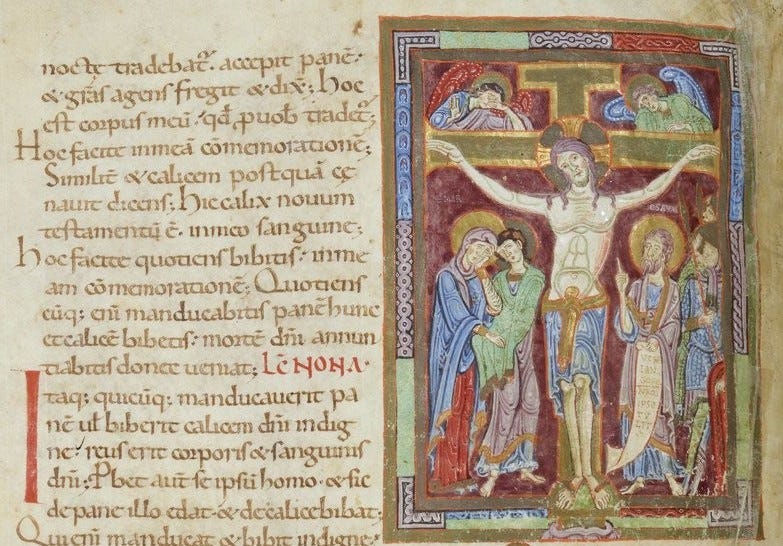

Aside: why aren’t there any early Clunaic manuscripts?

Well, there are, but frankly, very few of them are much to look at. Almost no illustrated manuscripts survive from early Cluny (10th–11th century), so we must use contemporary Burgundian and German monastic art to represent the visual world of Odo’s era.

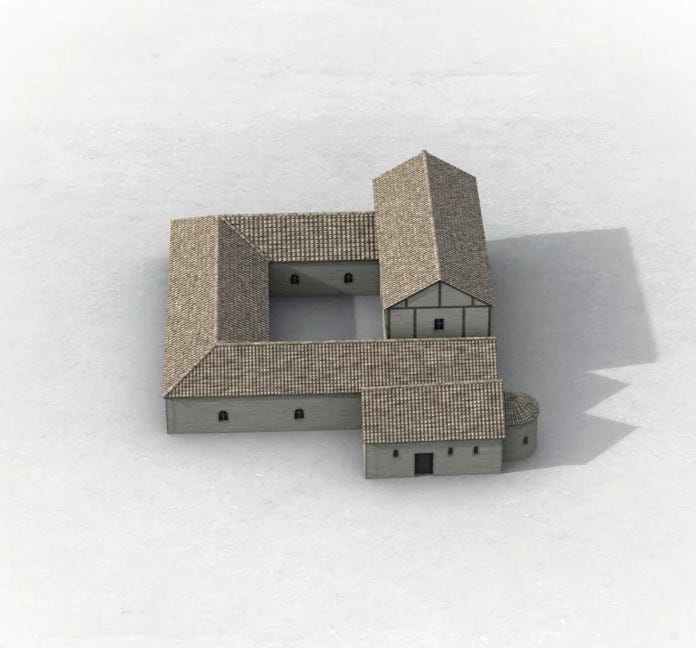

It’s been difficult in writing these sections to find images from the actual monasteries of the period, simply because almost nothing physical survives from Cluny’s first century. The early monks lived with a kind of austere practicality: their books were functional tools for praying the Office, not luxury objects meant to impress posterity, and the first church was small, plain, and built for use rather than display. Most of the manuscripts from Odo’s time were copied on modest parchment, read and used to bits and replaced when worn, or absorbed into later liturgical books.

It’s not that brilliant illumination wasn’t a thing in the early 10th century, it’s that Cluny in 927 - Cluny I - was small, obscure and poor, not a big, rich royal abbey endowed with treasures or imperial favour - like a scriptorium staffed with trained professional illuminators. It began as a modest, almost precarious foundation, a small community tucked into the Burgundian countryside with little more than a clear rule of life and the protection of its extraordinary charter.

And no one will be surprised to hear that whatever little still existed by the eighteenth century was largely swept away in the devastation of the French Revolution’s spiritual pogroms. Cluny’s library, archives and much of its stonework were destroyed or scattered. So when we try to visualise the world of Odo and his monks, we often have to rely on contemporary monastic centres elsewhere - like Reichenau Abbey - that were shaped by the same spiritual and cultural currents, even if the original Cluniac artefacts themselves have vanished.

Who was Odo?

St. Odo (c. 879–942) was the second abbot of Cluny and the figure who developed William of Aquitaine’s legal experiment into a genuine monastic reform. Born near Tours he was educated in the fading Carolingian intellectual tradition. As a noble child, Odo had been raised in royal courts, having served as a page under Duke William with whom he enjoyed a relationship for the rest of his career.

He later received the classical medieval secondary education in letters: literature, the Church Fathers, music and poetry at the famous church school of St. Martin of Tours, one of Europe’s great pilgrimage centres, where he was eventually tonsured as a canon. While at this great centre of learning, Odo was shocked by the delicacy and lack of spiritual seriousness of the canons and monks of Tours. When he returned at the end of his theology course, he adopted a rigorous ascetic lifestyle after deeply studying the Rule of St. Benedict.

After three years of a solitary ascetic practice at Tours, he renounced his canonry and decamped to Beaume, receiving the Benedictine habit from Abbot Berno.

What was going on at Beaume?

Beaume, a model for and precursor to Cluny, is thought to have been founded originally by Saint Columbanus, which would place its foundation in the late sixth century. It had a long history of trouble and disruption from secular powers, very much of the kind Duke William’s charter was intended to avoid for Cluny.

It seems Beaume was to be a test of the later Cluniac experiment. The turmoil it suffered meant it had had to be re-founded at least twice, the second time by Berno about 890. Pope Formosus appointed Berno as abbot and took Beaume’s land and incomes out of the hands of local bishops and secular princes and placed the monastery directly under the jurisdiction of the Holy See. Notably, the pope guaranteed the right of the community to elect its own abbot.

Odo’s reputation for learning combined with his great personal asceticism and an uncompromising commitment to the Rule of St Benedict, preceded him - and it helped that he arrived at Beaume (about 909) with a treasure of 100 books. Berno promptly made him master of the abbey school. He is thought to have been at the centre of the creation of the Cluny experiment; “Odo the deacon” is one of the signatures on Duke William’s original charter.

The start of the Cluny experiment

Upon Berno’s death in 927, three of the six monasteries under his authority, including Cluny, went to Odo who made the Divine Office the immovable centre of community life. Under his leadership, Cluny became known for disciplined common life, solemn liturgy and a seriousness of purpose rare in tenth century monastic life.

Cluny at this time would have been the Le Barroux of its age; a community that grew from obscurity to stand out as a vivid anomaly against the prevailing landscape of dreary religious decline. Where most monasteries were shrinking, compromised, or collapsing under lay control, Cluny appeared almost shockingly faithful, disciplined and liturgically alive. Its monks kept the full Divine Office and the monastic church was in constant use for the liturgy, when many places had reduced it to the bare minimum.

And as we have seen with our contemporary monastic reforms - Le Barroux, Clear Creek, Fontgombault and most recently Norcia - this discipline and faithfulness proved irresistibly attractive to new vocations and lay patrons alike. Under Abbot Odo, lay donations of land came to an average of 5 per year, mostly coming from donors living in the neighbourhood of the monastery.

Upon becoming abbot, Odo also set about a lifelong campaign to popes and kings for privileges and guarantees to protect the provisions of Duke William’s charter. One of these guarantees was a charter from Pope John XI1 in 940 that allowed Cluny to receive any monk of any other monastery,2 because most of the others have “swerved from their purpose,” falling into laxity, worldliness, or the grip of lay control.

The reforming reputation of Cluny grew to the point where Odo was asked to take over the governance of several existing monasteries. He his list of monastic “conquests” is impressive: Romainmôtier, Aurillac, Fleury, Sarlat, Tulle, Saint-Allyre of Clermont, Saint-Pierre-le-Vif, St. Paul Major (Rome), St. Elias in Nepi, Farfa, St. Mary on the Aventine, Montecassino, and Saint-Julien of Tours3.

With his saintly reputation, Odo also exercised wide influence in politics where Kings and nobles sought him as a mediator of disputes. He made peace between Alberic II of Rome4, and Hugh of Italy5 during their struggle for rulership of the papal city. In thanks for help resolving the situation in Rome, Alberic granted Odo control over several monasteries in Rome.

At the time of Odo’s death in 942, the community had expanded well beyond its original handful of monks, its observance of the Rule was renowned across the kingdom, and a growing number of monasteries and priories - some reformed directly by Odo, others voluntarily seeking Cluny’s protection - were looking to it as a model of stability and authentic Benedictine life. It was not yet the vast “monastic empire” of later centuries, but the essential foundations had been laid: a credible spiritual authority, a network of houses drawn into its orbit, and the legal freedoms that made its extraordinary future possible.

The glories of high medieval Cluny were still far in the future, but Odo had laid the necessary spiritual groundwork. Without his clarity and intensity, Cluny would never have become the spiritual powerhouse that was to shape medieval Europe.

John XI was the son of the notorious Marozia from her adulterous affair with Pope Sergius III, and reigned at the centre of what would later be called the “Saeculum Obscurum,” the period considered the absolute rock-bottom of morals and discipline for the western Church and the papacy. We introduced it here:

Poaching monks from other monasteries has always been frowned on in monastic culture, and still is today, so this extremely unusual permission hints at the seriousness of the situation.

Source: Encyclopaedia Britannica St. Odo of Cluny.

Son of Marozia and her lawful husband, Alberic Theophylact of Spoleto.

Marozia’s second husband for whom she had tried to overthrow her own son. After Alberic won supremacy, he sensibly locked up his mother for the rest of her life.

Beautiful post. I don’t know what the function is called, but I would love to be able to click and zoom embedded images to see detail more closely. Keep up the great work!

This is super; thank you Hillary!

Can you recommend any further reading?