We live in a time when artistic “originality” is elevated to a kind of moral requirement. We’re taught from childhood that “copying is bad”. Terms like “derivative” are always used in a pejorative sense by art critics.

But in Christian sacred art, since the 6th century, the goal was to communicate very specific truths of the Faith, which means our obsession with originality and novelty would have been rejected by our spiritual ancestors. Using established visual representations ensured that everyone, regardless of literacy, language or cultural background, could understand the scene or figure depicted.

In the next few public posts, we’re going to explore the concept of iconographic prototypes, and how iconography has influenced culture and history and why it’s got renewed crucial importance today.

The Sacred Images Project: Early Christian Art and Culture is a reader-supported publication, which means there’s no annoying ads, but also no advert revenue to keep the lights on and the kitties fed. There are lots of plans afoot, and paid posts are going to be getting more in depth as we go along, but it’s a full time job to create this content. So, I hope if you’ve found some value in this work, you’ll consider a free or paid subscription.

What are iconographic prototypes?

No, you don't need to make up your own personal visual language. The Church has done that for you.

For centuries, humanity has relied on visual symbols as well as verbal language to communicate complex ideas and stories. When we talk about something, a movie star or a famous building, being “iconic” we are unconsciously using this ancient concept. This is because art is a kind of language; it always carries a message that can be “read” by the viewer. To convey a deliberate and specific message, that will be understood by everyone the same way, the works have to use a set of symbols - words, phrases and meanings - that everyone knows.

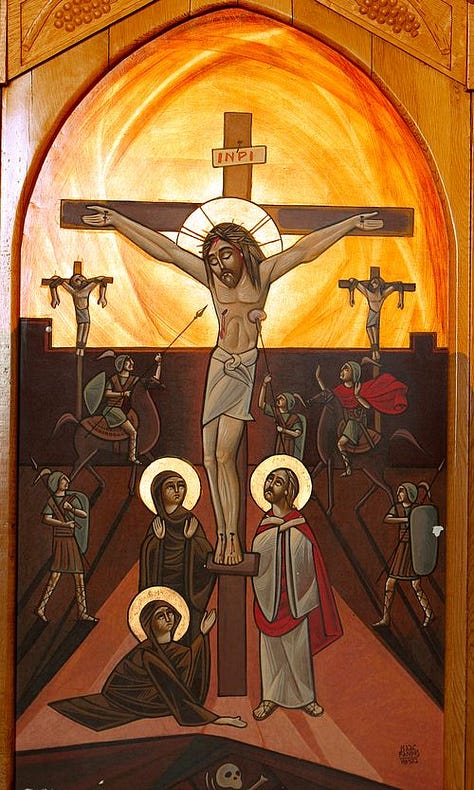

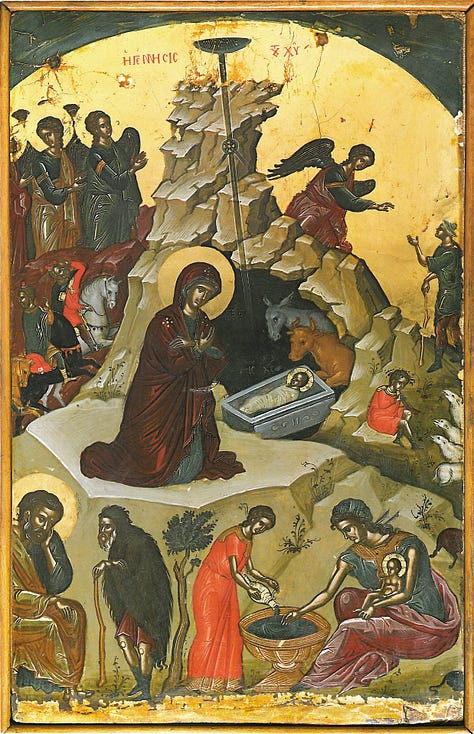

In Christian sacred art, the language is called “prototypes”. You instantly recognise the iconographic language even if you don’t know you know. This is one of the main ways the stories - and their theological meanings - of Christianity have been sunk into and diffused throughout our many cultures and have created the pan-Christian culture that we used to call Christendom.

This visual language is known by nearly everyone living in what we now call “western” countries, whether they are Christian believers or not. And if you are in any way a practicing Christian, you probably recognise all these images, at least in a general way, instantly.

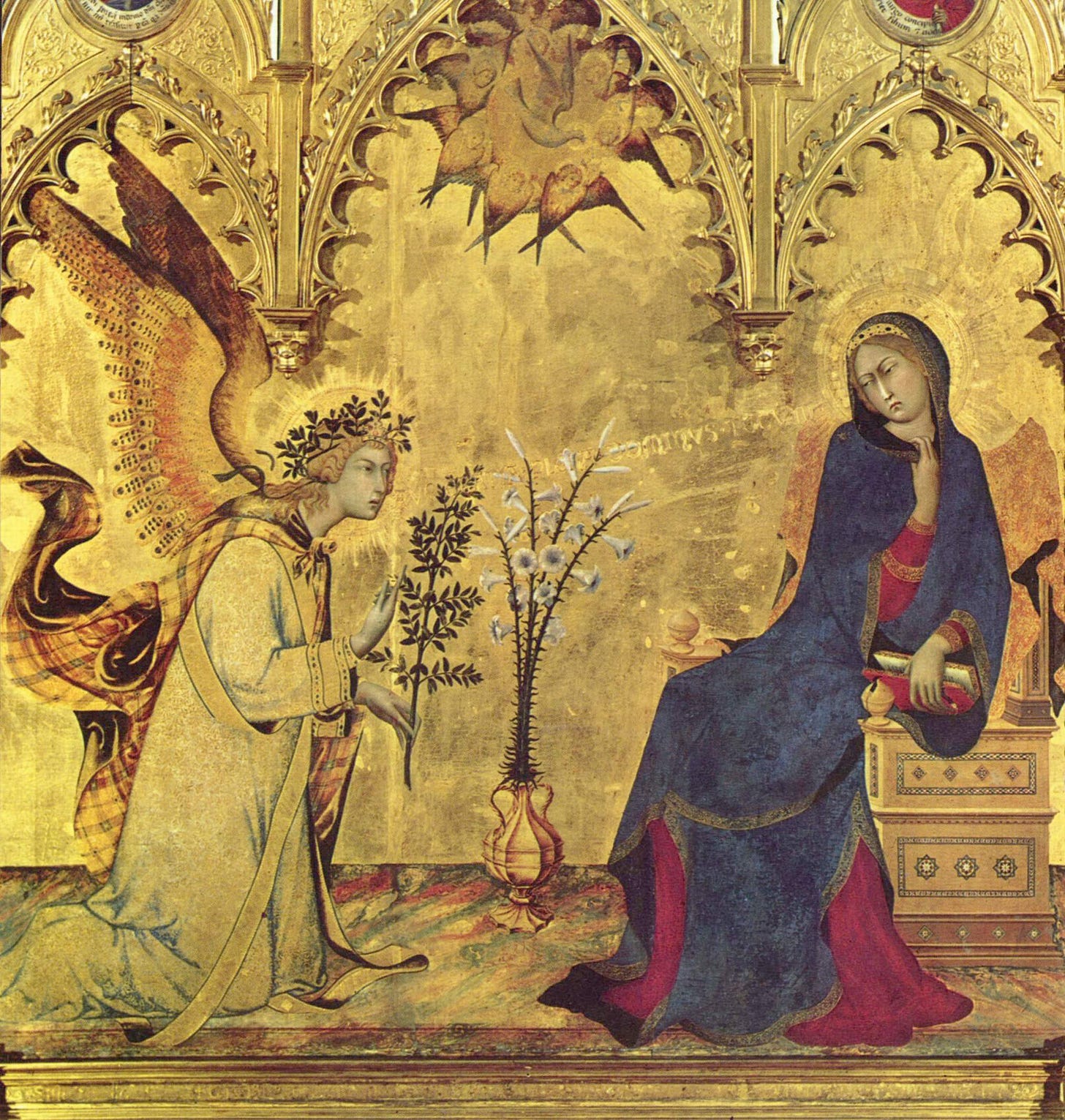

So, you know what I’m talking about when I say I’m painting “an Annunciation” as a commission. The Annunciation is one example of a “prototype”; a set of images that not only describe a historical event, but what it means theologically.

Fun Googling: learn to recognise four or five more iconographic prototypes that are used and instantly recognisable in both the Eastern and Western Church. Can you think of any that are normally found only on one side or the other? (hint: the Sacred Heart? Our Lady of Fatima? Have you heard of “the Protecting Veil”?)

We know it means the image of the moment when the Virgin Mary was told by the archangel Gabriel that she would bear the Son of God. But crucially, it was when she symbolically undid the sin of Eve who refused obedience to God in the Garden of Eden. By saying “fiat mihi” - let it be done unto me - Mary corrected the original fault, and this allowed the next stage of salvation history to go forward.

Iconographic prototypes are established visual representations that depict biblical figures, saints, theological concepts, and narratives. They are a kind of visual language, allowing artists to communicate complex theological and historical ideas to viewers, regardless of literacy or cultural background.

The prototypes can be quite complex, incorporating many individual figures and symbols. And these symbols are standardised so we know what each of the elements in this painting represents. Even when the image shows a moment in earthly history, a Biblical story that happened to real people, there are always symbols that form, so to speak, the individual “words” of the story so we know we are not hearing a mere story, but a greater theological reality. Because there’s always more to a story than just what happened.

Obviously we understand this instinctively. We know there wasn’t really a white pigeon fluttering about inside the house that day. We know without thinking about it that these are symbolic images.

The Virgin probably likes lilies, but the presence of a vase of them isn’t meant to be a simple representation of what she might have had in the house at the time. Iconographically-based sacred art, as I’ve said elsewhere, doesn’t follow the modern standard of representational art; it’s not supposed to be a snapshot by a time traveller.

We also know that angels don’t have wings and the Virgin didn’t live in a Gothic palace. What do these elements of the image symbolise?

How it started: 8th century iconoclasm and what happened next

In the east the concept of iconographic prototypes is still well understood and consciously followed by iconographers. The concept was formally codified after the 1st Iconoclastic crisis by the Second Council of Nicaea in 787.

Iconoclasm in a ridiculously small nutshell: would you die for an icon?

Iconoclasts, including emperors Leo III and Leo V the Armenian, under the growing influence of Islamic and Jewish thinkers, argued against the veneration of icons. They cited biblical passages prohibiting the worship of graven images and feared that venerating icons could lead to idolatry. They accused the veneration of icons of being a distraction from true piety and a source of corruption.

Iconodules, primarily theologians and monastic communities, defended the use of icons. They argued that icons served as a bridge, helping worshippers connect with the spiritual realm. They emphasized that veneration was directed towards the person or event depicted, not the physical object itself, and served as a form of honouring and remembering sacred figures.

This heated debate led to two distinct periods of iconoclasm, marked by the destruction of religious imagery and persecution of those who disagreed with the ruling ideology.

Since the iconoclastic position was held by the civil authorities and was supported among the leadership of the Church, Iconodules often suffered persecution. Though the idea would baffle a modern Christian, many suffered torture and even martyrdom for their defence of religious images, as well as exile and imprisonment. Loss of clerical position, public denunciation and shaming and confiscation of property and all the powers of the state was leveraged against the use of icons.

How did it end?

1Political shifts: The death of Emperor Theophilus, a fervent iconoclast, in 842 marked a crucial turning point. His widow, Empress Irene, who held the reins of power as regent for their young son, recognizing the widespread public dissatisfaction with iconoclasm, she took action.

The Second Council of Nicaea (787)2: Emperor Constantine VI3 convened the Second Council of Nicaea. This council officially condemned iconoclasm and reinstated the veneration of icons within the Church as well as intercessory prayer to saints, with which veneration of icons was intimately connected. The council established guidelines for the creation and use of icons, attempting to strike a balance between honouring religious imagery and preventing idolatry.

Public support for icons: Throughout the iconoclastic periods, popular resistance and devotion to icons persisted among the general public. Monks, nuns, and ordinary citizens often defied the official edicts, engaging in acts of hidden veneration, public protests and even martyrdom. This unwavering public support for icons served as a constant source of pressure on iconoclast emperors and churchmen.

The role of theologians: Individuals like Theodore the Studite and Stephen the Younger actively opposed iconoclasm throughout their lives. Their writings, debates, and acts of defiance kept the issue alive and inspired others to resist. Additionally, the theological arguments put forth by John of Damascus and other earlier defenders of icons provided a strong intellectual foundation, based on Scripture and Tradition, for the eventual restoration of icon veneration.

Fun Googling: Look up the names John of Damascus, Theodore the Studite, Germanus of Constantinople, and Empress Irene and learn more about their many years of struggle against oppression of the Faith by the State and even parts of the Church. NB: one Patriarch of Constantinople was an iconoclast and used that position to suppress the use of icons.

Nicaea II: icons are equal to Scripture

It will sound pretty shocking to modern Latin (western) Catholic ears, but one of the great ecumenical councils, the last of the “undivided Church,” said that icons are equal to Scripture in conveying the Christian Faith.

And they said it pretty plainly:

If anyone does not confess that Christ our God can be represented in His humanity, let him be anathema.

If anyone does not accept representation in art of evangelical scenes, let him be anathema.

If anyone does not salute such representations as standing for the Lord and His saints, let him be anathema.

If anyone rejects any written or unwritten tradition of the Church, let him be anathema.

… “written or unwritten tradition of the Church”…

What was the significance of this opening salvo of anathemas? It established that visual representations are not only legitimate but required. These images must be “saluted” as “standing for the Lord and His saints”. And most importantly that they constitute the “unwritten tradition of the Church”. That is, on a level equal to Scripture and its formal interpretation.

That, in fact, icons are an integral part of the deposit of what we might call in archaic English “holy writ”. This naturally meant that the creation of icons had to be as careful as the translation and copying of Scripture.

So, obviously it’s going to be very important to make sure that icons are created in a particular way, according to particular standards, to make sure that error or even heresy doesn’t enter the Church through them.

That’s enough for now. In Part II we’ll look more closely at what Nicaea said and how that was followed and developed into the various iconographic prototypes and how different styles developed throughout the Christian world and across the centuries.

Bonus round: St. John of Damascus talks some plain common sense

We do still have some of the exact words of some of the people who lived through this crisis and defended the Faith, and they’re surprisingly relevant and comprehensible to us today.

St. John of Damascus (c. 676—749)

Defence Against Those Who Oppose Holy Images

We have outgrown superstitious error, and know God in truth, worshipping him alone, enjoying the fullness of his knowledge. We are no longer children but adults. We receive our habit of mind from God, and know what may be depicted and what may not. The Scripture says, “You have not seen his face.” [Ex. 33;20] How wise the Law is! How could one depict the invisible? How picture the inconceivable? How could one express to the limitless, the immeasurable, the invisible? How give infinity a shape? How paint immortality? How put mystery in one place?

But when you think of God, who is a pure spirit, becoming man for your sake, then you can clothe him in a human form. When the invisible becomes visible to the eye, you may then draw his form. When he who is a pure spirit, immeasurable in the boundlessness of his own nature, existing as God, takes on the form of a servant and a body of flesh, then you may draw his likeness, and show it to anyone who is willing to contemplate it. Depict his coming down, his virgin birth, his baptism in the Jordan, his transfiguration on Mt Tabor, his all-powerful sufferings, his death and miracles, the proofs of his deity, the deeds he performed in the flesh through divine power, his saving Cross, his grave, his resurrection and his ascent into heaven. Give to it all the endurance of engraving and colour. Have no fear or anxiety; not all veneration is the same.

Thanks for reading to the end. I hope you enjoyed this exploration of the history and meaning of our great shared artistic patrimony.

If you’d like to help me continue this work, I hope you’ll consider taking out a paid subscription. It’s just $9/month. Since starting this work in earnest in November last year, it has blossomed into a full time job and the more I do it the more excited I get about it.

Unfortunately, it isn’t yet at the level with subscriptions of full time pay. I want to continue to explore this fascinating aspect of our faith, but I need your help.

If you’d prefer to be a patron with a monthly donation or make a one-time donation, you can click on my studio blog, Hilary White; Sacred Art. Everyone who sets up a recurring donation of $9/month or more will receive a complimentary subscription here.

Many thanks to those who have already signed up and are coming along.

Those currently suffering under similar circumstances current in our own time should take note that it was not a change of pope, the issuance of a document or any other single act that ended the 60 years of persecution and suppression of this key aspect of the Christian faith.

The Council alone, although it was definitive and issued clear anathemas, was not enough to resolve the crisis. And it flared up again decades later. Another really significant point about Nicaea II was that the pope wasn’t there. It wasn’t called by a pope, but by an Emperor. Pope Adrian I (772-795 AD) was invited to participate in the council by the emperor Constantine VI and Empress Irene. The pope sent delegates, an abbot and an archbishop. The decrees of the council were issued before they received papal approval. Relations between the Eastern and Western Churches were strained at this time and the influence of Empress Irene in the iconoclastic problem was one of the issues that started the cracks between the Eastern and Western Church that led to the Great Schism.

Officially it was Constantine VI, but since he was a boy of seven in reality it was his mother and regent Irene, an iconodule, who was the force behind the defeat of iconoclasm.

Excellent! Thank you. Looking forward to more.

Very enlightening. Thank you!