A visual shout of triumph: the first Roman Imperial Christian mosaics

The Mausoleum of Constantina1, (Santa Costanza) was built in the 4th century for the daughter of the emperor Constantine the Great who died in 354. It holds some of the earliest mosaics created with specific and overt Christian themes, made possible by Constantina’s father’s decree legalising the faith throughout the empire, the Edict of Milan, in 313.

It still stands today as one of the most important examples of the dawn of public Christian sacred art that emerged from the secrecy of the times of persecution with a fully developed theological language.

The transition of Christianity in the 4th to 6th centuries from a persecuted minority faith, practiced in hiding, to the dominant religion of the Roman Empire at the peak of its power, transformed not only the spiritual landscape but also the artistic one.

Mosaics, an art form long favoured by the Romans for its durability and splendour, became a medium for expressing the glory of the Christian faith. In this transitional period, the cities of Rome and Ravenna stood as the principal centres of this transformation in the Western Empire, producing some of the most remarkable examples of early Christian mosaic art.

They vividly reflect the blending of Roman artistic traditions with emerging Christian iconographic meaning, that is, theological meaning. The grape harvest scenes, for instance, intertwine pagan Bacchic imagery with Eucharistic symbolism, transforming familiar motifs into theological expressions.

This building represents the precise moment when Christian art began to confidently assert itself within the imperial and cultural fabric of the Roman world.

At the Sacred Images Project we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. The publication is supported by subscriptions, so apart from plugging my shop, there is no advertising or pop-ups. It’s my full time job, but it’s still not bringing a full time income, so I can’t yet provide all the things I want to and am planning for.

You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week.

For $9/month you also get the second half of the third post, plus a weekly paywalled in-depth article on our great sacred patrimony. There are also occasional extras like downloadable exclusive high resolution printable images, ebooks, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts.

Rome: The Birthplace of Christian Mosaics

As the heart of the empire, at least at first. Constantine moved the government of the empire to Byzantium in 330, not even a full 20 years after the Edict of Milan. Of course, it took a long time for Rome’s prominence as a cultural centre to start to decline, and Constantinople’s to rise, but the emperor took a lot of talent with him.

Still, as the heart of the empire, and the natural centre of the Western Empire, Rome remained a natural starting point for the development of Christian mosaics. Rome was a starting point for the development of Christian mosaic art form. Though relatively few mosaics from before the 5th century survive, even in restored form, what we do have tell us a story of Christianity already firmly confident about the rightness of its claims, and well versed in theological nuance with a fully developed visual theological vocabulary, even as it stepped out of the shadows.

Mosaics such as these depict a faith that had grown in sanctity and doctrinal confidence while still in the depths of brutal state persecution, and had come forth ready to assert its place in the public and imperial sphere.

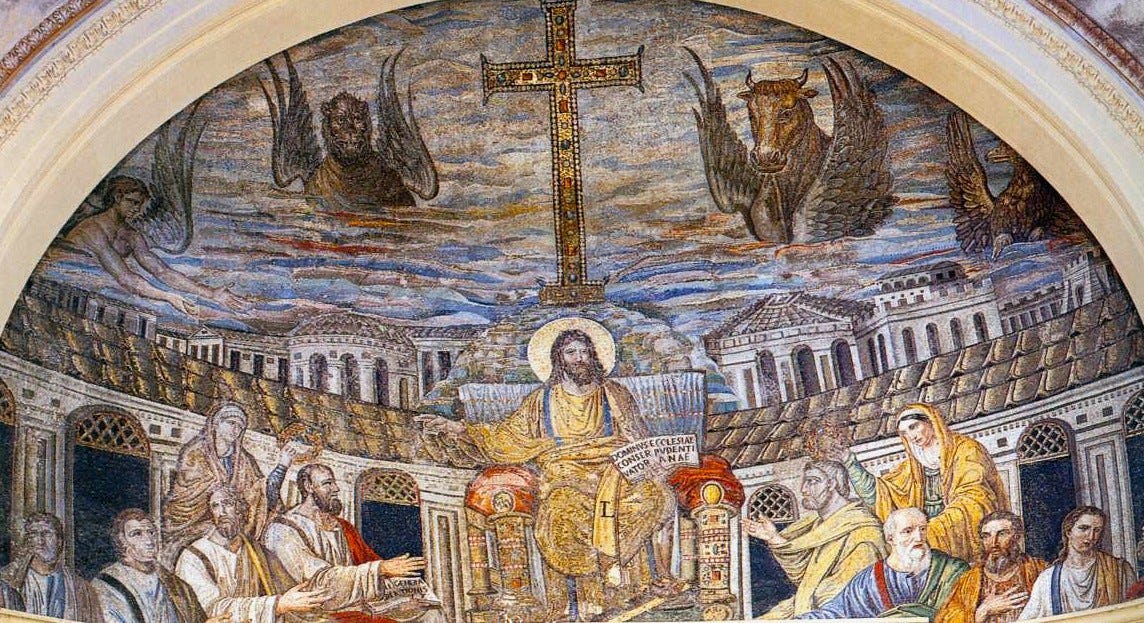

In works like those of Santa Pudenziana, Christ is portrayed with imperial authority, robed in gold, attended by angelic beings, the “Tetramorphs2” symbolising the four Gospel writers, and surrounded by apostles clad in Roman togas of the senatorial class, as if to claim the visual language of the empire for the kingdom of heaven.

Why do so few of the earliest works survive? It takes a great deal of effort to keep such works in good condition and the mosaics that we have from the early centuries have been restored countless times over the centuries. Weathering, natural disasters, and simple aging have taken their toll. Many mosaics were also lost during renovations or were intentionally destroyed as tastes and religious practices changed.

Early Christian mosaics often reused existing Roman materials and spaces, making them vulnerable to later renovations or destruction during medieval and Baroque periods. The transitional nature of the 4th century is shown by the scarcity of these works, that we know were created but have since been lost. In this early moment when Christianity was emerging from persecution, churches were often modest compared to the grander imperial projects of the 5th century.

The earliest surviving examples, such as those in the Basilica of Santa Pudenziana (c. 390), and the triumphal arch of Santa Maria Maggiore (5th century), reflect a transitional period in which classical styles and techniques were adapted to Christian themes. These were dedicated to the Church’s mission of this time to assert its place within the Roman imperial tradition while simultaneously celebrating the uniqueness of Christian revelation.

Ravenna: The Jewel of Byzantine Italy

Mausoleum of Galla Placidia

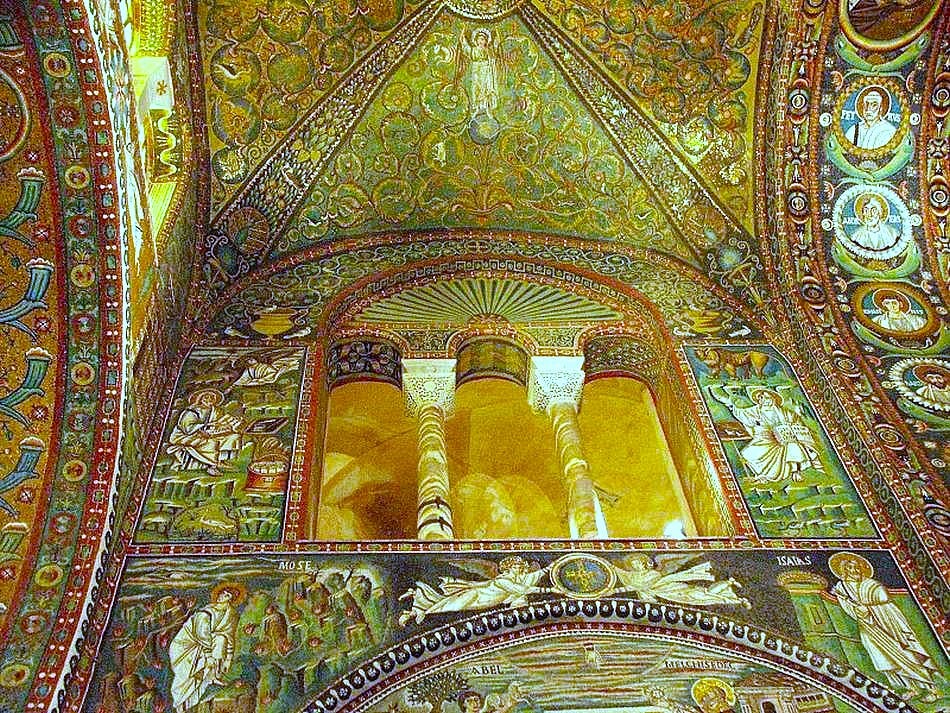

Ravenna rose to prominence as the capital of the Western Roman Empire in 402 and later as a key centre of Byzantine influence in Italy. This dual identity is vividly reflected in its mosaics, which combine Roman naturalism with the more symbolic and hierarchical style of Byzantine art. Ravenna is, of course, probably most famous for achieving the pinnacle of grandeur of the mosaic art, and it is still known today as the “capital” of the form in the west.

The mosaics of the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia (c. 425) represent an early milestone. Their rich colours, celestial themes, and detailed craftsmanship exemplify a shift towards a more otherworldly aesthetic.

The figure of Christ as the Good Shepherd, dressed in imperial gold and purple, marks a departure from the humble pastoral imagery of earlier centuries, emphasizing his dual role as shepherd and sovereign.

San Vitale

In the 6th century, during the reign of Emperor Justinian, Ravenna reached its artistic zenith. The mosaics of San Vitale (completed in 547) and Sant’Apollinare Nuovo encapsulate the Byzantine vision of a cosmos ordered by divine rule.

In San Vitale, the famous panels of Justinian and Theodora, surrounded by their retinues, blur the lines between imperial authority and sacred ritual, portraying the emperor and empress as Christ’s representatives on earth.

Spectacular, must-see, 360 degree panorama of San Vitale available on Google Maps here.

Artistic and Theological Innovations

The mosaics of Rome and Ravenna share several defining characteristics:

The Use of Gold Backgrounds: By the 5th century, gold became a dominant feature, symbolizing the unchanging light of heaven and lending a sense of divine transcendence to the scenes.

Hierarchical Composition: Figures are often arranged to reflect their spiritual importance, with Christ or the Virgin Mary prominently centred and elevated, often depicted larger than the other human figures.

Integration of Symbolism: From the cross-shaped nimbus around Christ’s head to the abundant use of lambs, doves, and vines, the iconography communicates theological truths in a visual language accessible to all believers.

Fully developed symbolism and Prototypes: Not only were biblical scenes and their theological importance understood and depicted by the artists, fully developed multi-figure iconographic prototypes that continued to be used unchanged through the Christian centuries came out of the catacombs.

Constantina, born in c. 320, was the eldest daughter of Constantine I. She is credited with the construction, in 342, of the first basilica dedicated to Saint Agnes, to which her mausoleum was attached. Only parts of the walls of the original Basilica of St. Agnes remain, but the mausoleum is in good condition. She was venerated as a saint in Rome since the 7th century.

Tetramorphs: the symbolic representations of the four Evangelists, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John through the imagery of four creatures: Matthew is pictured as a man, Mark as a lion, Luke as an ox, and John as an eagle. This representation is derived from prophetic visions in Ezekiel and Revelation. The word tetramorph comes from a Greek word meaning “of four shapes.”

The mosaics in Ravenna are among my absolute favourites. Thank you for this wonderful post!

I think it’s so powerful to reflect on how mosaic art was used for flooring for centuries. People in ancient times cared so much about their homes and the very floor that their guests tread on that they were willing to decorate it with such incredible detail and craftsmanship. It blows my mind, having created mosaics myself, how so much painstaking effort went into floors, remote corners, and hardly-visible apses for that matter…a type of respect for architecture and its power that is in many ways lost today.