Island Kings and Mystic Saints at the Dawn of English Christianity

Bringing the light to the barbarous English

It was a time of tribal warfare between petty kings, when swords clashed in the misty fields of Northumbria, and men fought for kingdoms that could vanish in a heartbeat. It is the beginning of the 6th century and Roman legions had long since abandoned Britain, leaving behind crumbling walls and fading memories of empire and the Pax Romana.

In the chaos that followed, the pagan gods again took hold of the people, their shrines standing tall over the scattered tribes of Saxons and Angles. But something new was stirring in the north; a light, fragile at first, but bright enough to pierce the gloom. It was the Gospel, carried by men who had no armies, only the Faith.

You may have heard the name, The Venerable Bede, and the Penguin Classics edition of his book might be on the shelf, but did you know it reads like a mystical fantasy adventure novel, to rival Tolkien? I had a copy of Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People for years before picking it up, and now it’s a permanent favourite. It’s nothing at all as I expected: it’s really a collection of short stories, filled with visions and visitations of angels, miraculous battles, and holy men communing with nature in ways that seem almost magical. I’m seriously surprised no one has ever made a high-budged CGI effects movie series about it.

And yet, it does have a clear narrative framework, that tells the story of a land where kings raise wooden crosses before battle, saints are warmed by otters, and ravens deliver gifts as tokens of repentance for mischievousness. This is no dry history, it’s a vivid, almost otherworldly journey into the very soul of early medieval Britain.

In today’s post for all subscribers, we’ll go back to the misty early days of English Christianity, a time when saints and kings walked the same paths, forging a new spiritual and political landscape in the cold and windy wilds of Britain. Through the lives of holy figures like St. Hilda, St. Oswald, St. Aidan, and St. Cuthbert, we’ll explore how faith took root in a land once dominated by paganism and violence, and how these remarkable individuals shaped the course of Christian history.

The Sacred Images Project is a reader-supported publication where we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. It’s my full time job, but it’s still not bringing a full time income. You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week.

For $9/month you also get the second half of the weekly Goodie Bag post, plus a weekly paywalled in-depth article on this great sacred patrimony, plus our Benedictine Book Club in the Substack Chat. There are also occasional extras like downloadable exclusive high resolution printable images, ebooks, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts.

If you would prefer to set up a recurring patronage in an amount of your choice, or make a one-off contribution, you can do that at my studio blog. Anyone who signs up for a patronage of $9/month or more will, of course, receive a complimentary subscription to the paid sections of The Sacred Images Project.

This helps me a lot because the patronages through the studio blog are not subject to the 10% Substack fee:

This is the site where I post photos of my own work as it develops. I have a shop there where some of my drawings and paintings are available for sale as prints, as well as some other items.

Today we take a slightly different approach - more novelistic - as we dive into the story of the earliest days of the English Church, where miracles, humility, and devotion transformed an island and its people forever.

The light that almost went out

The little flickering flame of Christianity had first been brought to Britain with the Romans - excavations along Hadrian’s Wall have uncovered early Christian symbols like the Chi-Rho carved into stones or found in personal items that would have belonged to Roman military men. At Vindolanda, one of the major forts along the wall, archaeologists have found several items that could suggest early Christian practices among Roman soldiers and local inhabitants.

Patricius, a Romanized Briton, was born and raised in Britain in the 5th century, likely in modern-day Wales or western England, which had a Christian presence from the time of the Roman occupation. He was kidnapped as a young man and taken to Ireland as a slave. But after escaping and returning home, he later felt the call from God to return to Ireland as a missionary. He is, of course, known to history as St. Patrick.

I’m happy to offer this little present for all our subscribers today, a page from the the Peterborough Psalter and Bestiary, a French Gothic manuscript of about 1400, held by the library of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. This downloadable PDF can be printed in high definition and framed, or used for making into an art project. It can be made into a colouring page for youngsters by tracing. I’ve included a black and white version to make this easier.

But with the fall of Rome, that little flaming seed was nearly lost. For two centuries, the faith survived only in pockets, scattered and fragile, barely more than a whisper amid the rising of the old pagan rites and tribal warfare for control of what the Romans left behind.

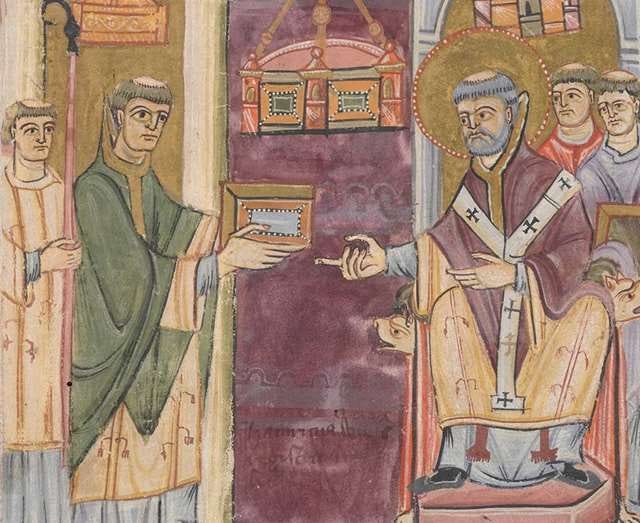

That is, until the arrival of a man named Augustine, sent by Pope Gregory the Great in 597 AD to the pagan shores of the Kingdom of Kent. Augustine, weary from his long journey, stood at the gates of King Æthelberht’s court, carrying a message that had been silent in the land for too long.

It wasn’t an easy mission, both the pope and Augustine knew, and he quailed a little. As they journeyed through Gaul, they heard terrifying stories about the barbaric nature of the Anglo-Saxons, their violent customs, and their unfamiliar language.

Frightened by these reports, Augustine and his group became anxious about continuing their mission. Augustine was so concerned that he returned to Gaul to seek Pope Gregory's permission to abandon the mission and turn back. However, Gregory responded with firm encouragement. In a letter, he urged Augustine to press on, reassuring him that the mission was divinely inspired and that God would protect and guide them.

With renewed determination, Augustine resumed the journey to Britain, where he eventually arrived in Kent and successfully converted King Æthelberht and many of his subjects, establishing Christianity in the region.

In the years that followed, Augustine established a Christian foothold in Kent in the south. But Kent was just the beginning. The northern realms - wilder, fiercer, and more untamed - were waiting for their moment. And that moment would come through a prince in exile, a wooden cross, and a battle under the watchful eyes of heaven.

Oswald and the Cross of Heavenfield

Far to the north, in the wild kingdom of Northumbria, a young prince named Oswald was preparing for war. He had been driven into exile after the death of his father, King Æthelfrith, by the pagan warlord Penda of Mercia. Exile had taken Oswald to the rocky, windswept island of Iona, where monks in simple robes spent their time in prayer, work and silence. Among them, Oswald learned about a different kind of king, one who died on a cross, not with sword in hand, but with open arms. And so, baptized in those cold northern waters, Oswald became a Christian.

When the time came for him to return to Northumbria and reclaim his throne, Oswald knew he could not do it alone. But he believed in something more powerful than armies. On the night before battle, his enemies camped nearby, waiting for the dawn when they would attack. Oswald knelt on the earth and planted a simple wooden cross into the soil. His men gathered around, and they prayed. "Let us all kneel," he said, “and together ask the true and living God, Almighty, to defend us from the haughty enemy.”

The next morning, in 634 AD, with the cross at his back, Oswald’s men surged forward and triumphed over the larger pagan army. The Battle of Heavenfield was won, and Oswald’s victory was seen as nothing less than a sign of divine favour. Northumbria was his, and now it would be Christ’s kingdom as well.

But Oswald knew that bringing Christianity to his people required more than royal decree. He needed someone who could walk among them, someone who understood the heart of the northern folk. His search led him to Aidan, a monk of great holiness, living on the island of Iona. When Oswald asked him to come, Aidan did not hesitate.

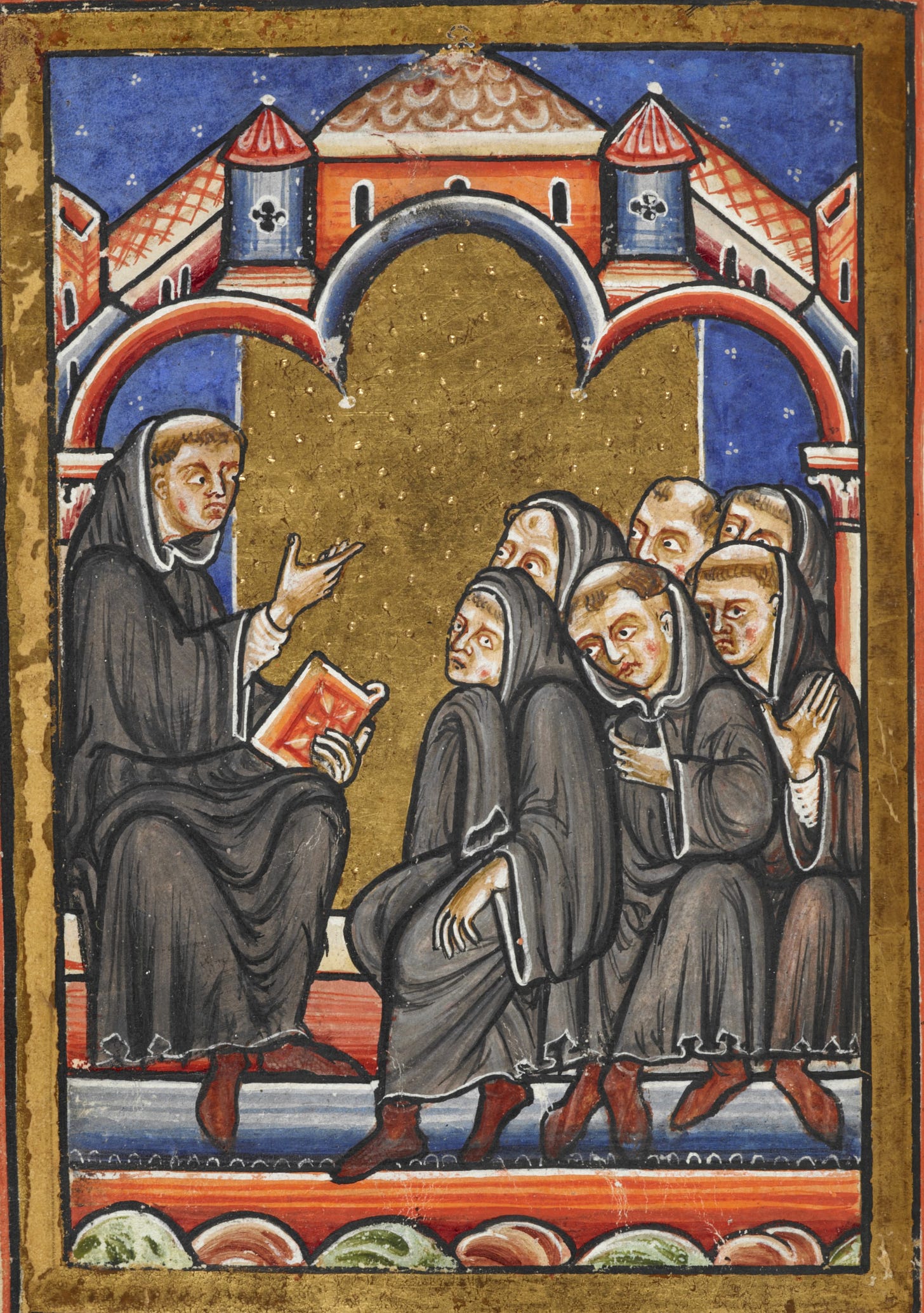

Aidan travelled to Northumbria, where he established the monastic community on the small island of Lindisfarne. From this base, Aidan and his fellow monks began their tireless work of evangelizing the region, walking from village to village, preaching, and baptizing. Their efforts, supported by Oswald, would transform Northumbria into a stronghold of Christianity in Britain.

At the site of Oswald’s death at the Battle of Maserfield (now believed to be Oswestry), where he was killed by Penda of Mercia, the ground where the king’s body fell became known for miraculous healings. People would take earth from the spot and mix it with water to drink, believing it had the power to heal illnesses. One such miracle involved a paralyzed girl who was healed when her family brought her to the site of the battle.

Aidan and Lindisfarne: A Monastic Beacon

The wind howled over the rocky shores of Lindisfarne, a tiny island just off the Northumbrian coast. It was a harsh place, lashed by the sea, but it suited Aidan perfectly. In 635 AD, he founded a monastery there, making it the spiritual heart of Northumbria. From this rugged outpost, Aidan began his mission. But unlike most, he did not ride a horse to reach the far-flung villages. No, Aidan walked. Barefoot.

Through rain and mist, Aidan went from village to village, teaching the Gospel in simple words, offering his cloak to those who had none, and sharing his food with the hungry. He was a man of deep humility, and his example spoke louder than any sermon. Even King Oswald, who offered him horses and riches, marvelled at the monk’s simplicity. Aidan preferred to walk the same paths as the people he served, his feet carrying him along dirt roads and across fields, where he would speak to shepherds and farmers about Christ.

Over time, Lindisfarne became more than a monastery. It became a beacon of faith, a place where monks would come to learn and to pray. Aidan’s example would inspire others to follow in his footsteps, men like Cedd and Chad, who would carry the Gospel to other corners of England.

Cuthbert: The Solitary Shepherd

Years later, another figure would rise from the quiet hills and rugged cliffs of Northumbria. His name was Cuthbert, (c. 634 to 687) a shepherd boy whose life would become one of legend. Cuthbert had always been a solitary soul, drawn to the lonely places where only the wind and the sea could be heard. One night, as he watched over his sheep, he saw a vision, a light in the sky, and angels carrying the soul of Aidan to heaven. The sight shook him to his core, and he knew that his life would never be the same.

Cuthbert entered the monastic life, first at Melrose Abbey and later at Lindisfarne. His days were spent in prayer and work, but it was his nights that would become famous. Every evening, Cuthbert would walk down to the shore, where he would wade into the icy waters of the North Sea. There, standing chest-deep in the freezing tide, he would pray for hours, his eyes fixed on the stars. When he finally returned to shore, it was said that otters would come to him, warming his feet and drying him with their fur.

Ravens, too, were drawn to him. One day, Cuthbert found them stealing straw from the roof of the house of the monastery’s servants. He scolded the birds and banished them from the island. To everyone’s amazement, they returned with a gift - a lump of pig fat, enough to waterproof the brothers’ boots for a season - which they humbly offered to him as an apology. Cuthbert forgave the naughty birds and they were allowed back.

Though Cuthbert loved the people, he longed for solitude. In his later years, he retreated to Inner Farne, a tiny island where he could be alone with God. Yet even there, pilgrims sought him out, and Cuthbert, ever gentle, would come to the shore to greet them.

After his death, Cuthbert’s body was found to be incorrupt, and his tomb became a place of pilgrimage. Durham Cathedral would later rise over his remains, but the stories of the holy man who loved both people and animals alike would live on.

The Story of the Angelic Guest

Cuthbert was serving as the guest-master at Ripon Abbey, a role that required him to care for any visitors to the monastery. One cold night, a stranger arrived at the monastery, appearing poor and weary from his travels. Cuthbert welcomed him warmly, offering food and shelter despite the harsh conditions outside. The monk treated the guest with great kindness, attending to all his needs.

After ensuring that the visitor was comfortable and well-fed, Cuthbert left him for the night, only to return the next morning to check on him. However, when he entered the guest house, he found that the visitor had vanished. No one had seen him leave, and there were no signs of his departure. Cuthbert soon realized that the stranger must have been an angel in disguise, sent by God to test his hospitality and kindness.

According to the account, Cuthbert believed that this mysterious visitor was a divine messenger, and the incident reaffirmed his dedication to serving others with humility and love, seeing Christ in every person he encountered.

The Story of the Mysterious Rider

While Cuthbert was traveling on foot, heading to a distant part of Northumbria to preach and care for the faithful, he became exhausted and hungry. The journey was long, and the harsh landscape of the North was unforgiving. As the day wore on, Cuthbert found himself alone and struggling to continue.

At this moment, a mysterious rider appeared, mounted on a splendid horse, and approached him. The rider was richly dressed, and his horse was well-kept, a stark contrast to the wild surroundings. The rider greeted Cuthbert warmly and offered him food and drink. Cuthbert, grateful but cautious, accepted the provisions, though he was perplexed by the sudden appearance of such a fine figure in the desolate wilderness.

After sharing the meal, the rider blessed Cuthbert and departed as suddenly as he had appeared, disappearing into the distance. Cuthbert believed that this strange rider was no ordinary traveller, but rather an angel or a heavenly messenger sent to aid him in his moment of need. The provisions sustained Cuthbert for the rest of his journey, allowing him to reach his destination and continue his ministry.

The Synod of Whitby: A Church United

While monks like Aidan and Cuthbert laboured for the faith, tensions were rising. The Christian traditions of the Celtic Church—rooted in places like Iona and Lindisfarne—did not always align with the Roman customs that had spread southward from Canterbury. The date of Easter and the style of monastic tonsures might seem minor to modern minds, but in the 7th century, these differences threatened the unity of the English Church.

In 664 AD, St. Hilda, the wise and formidable abbess of Whitby Abbey, called for a great council. The Synod of Whitby brought together leaders from both the Roman and Celtic traditions to settle the disputes that had divided the church. Hilda herself was sympathetic to the Celtic ways, but after much debate, the decision was made to follow the Roman customs.

This moment, though tense, was a turning point for English Christianity. It ensured that the English Church would be united with the broader Christian world, and it brought peace between the Roman and Celtic traditions. Under Hilda’s guidance, Whitby became not just a centre of spiritual power but also of learning, producing saints, bishops, and even the first known English poet, Caedmon.

The Legacy of the Saints

By the time Bede put quill to parchment in the early 8th century, the story of the English Church had already been shaped by the lives of countless saints, kings, and monks. Oswald, Aidan, and Cuthbert, and Hilda, had transformed a once-pagan land into one where the cross stood tall. Their stories, woven into the landscape of hills and abbeys, would endure for centuries.

It was a time when miracles walked hand in hand with men, when ravens brought gifts to saints and kings knelt before crosses. The early English saints carried the Gospel into a land of darkness, bringing light that would not fade. Their legacy reminds us that faith is not just the work of the strong, but of the humble, the gentle, and those who walk barefoot across fields, speaking softly of Christ.

I cannot recommend Bede strongly enough, and we have quite a lot of his writing. You can find him and stories of other saints and kings of this time in Penguin Classics.

I made a wonderful visit to Lindisfarne last year. There's a convenient bus from the charming border town of Berwick upon Tweed for those without a car.

Also not to be missed are the remains of the double abbey of Monkwearmouth (now part of Sunderland) and Jarrow (a suburb of Newcastle today). Both surviving churches are mighty impressive with significant parts extant from Bede's day, and at Jarrow there's a superb museum dedicated to Bede and his times as well as a reproduction monastic farm.

Both are reachable by Newcastle Metro and bus.

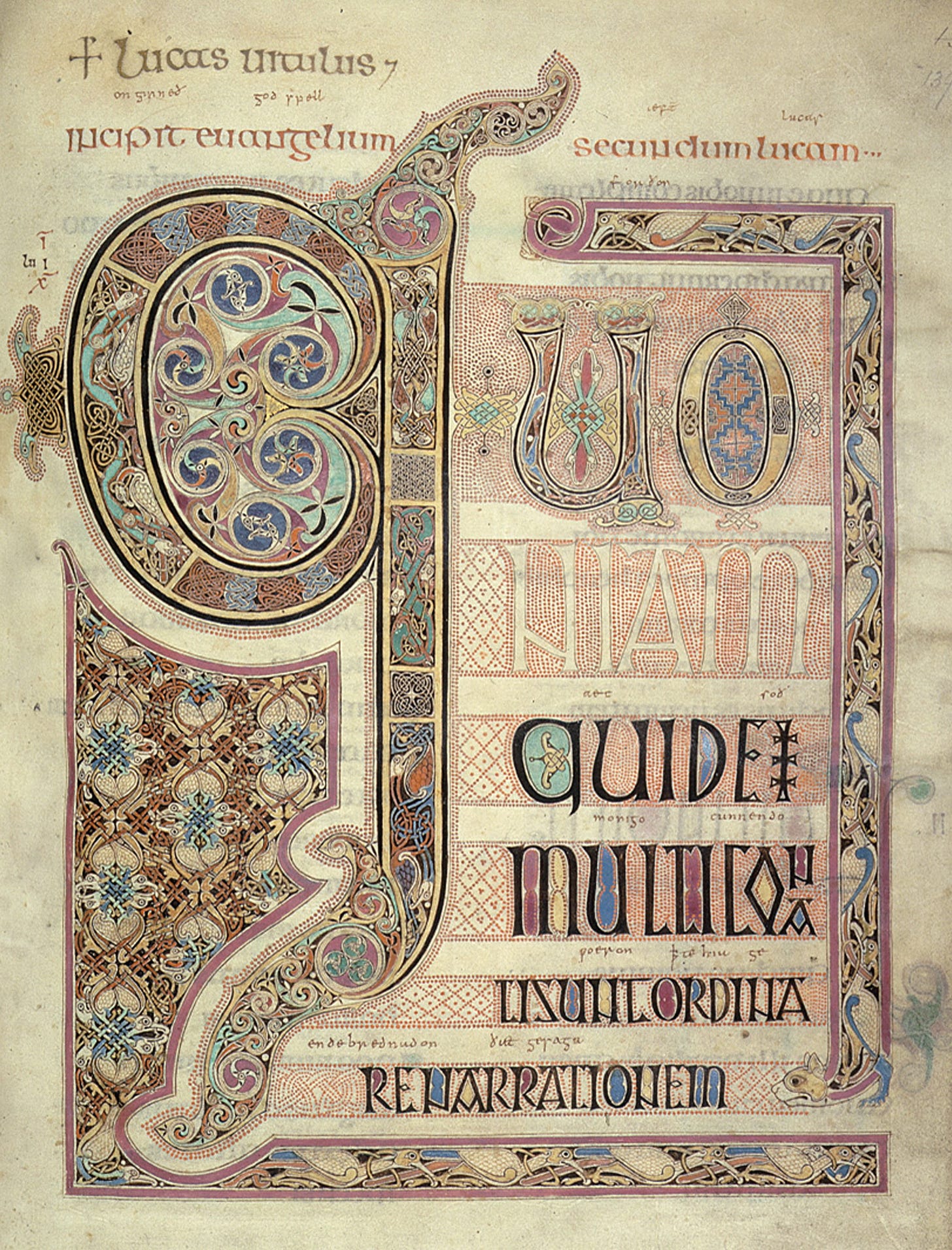

You can have all of our airports, electricity, surgeries, life expectancy, central heating, indoor plumbing, automobiles and right down the list -- all of it combined pales badly in comparison to one page of such an illumnated manuscript.

Those people made the paper, the ink, the pens and recorded their souls on those images. We are blessed indeed that such wonders still exist. And we should be a bit embarrassed to point to our progress.