Know your sacred art terms: what are "the Canons"?

Hint: they're the framework of the universe

Iconography, the mathematics of human beings and the nature of reality

In my early 20s I decided to sign up for some “adult upgrading” courses put on by the city of Vancouver to get myself up to speed in Math. I didn’t hold out much hope that I would succeed since I’d always had a terrible time with maths in school. This was partly because my mother, whose undergraduate degree was in mathematics and marine biology, expected me to pick it up as easily and in the same way she did. The resulting home rows, that went on throughout my school years, were so terrible that it damaged our relationship for the rest of her life. So, to say math was fraught and a touchy subject for me … well…

So imagine my surprise when, after I’d been away from home for several years, I took to it like a duck to water - a duck whose ducklinghood experience had been so traumatic he hated the sight of water… so, rather a surprised duck. I zoomed ahead of the other students in my first class, and took extra work home. Then I signed up for more, especially as much geometry as I could. I’d never studied anything quite so satisfying.

I will never forget the moment, in the middle of graphing some Euclidian problem, when I realised that mathematics, especially geometry, was like a map of the invisible “stuff” that the universe, that reality itself, was made of. And I really wanted to know how I could get in on that.

When we start talking about “the canons” keep this idea in your mind; they are part of that mathematical map of reality.

The Sacred Images Project is a reader-supported publication where we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. It’s my full time job, but it’s still not bringing a full time income, so I can’t yet provide all the things I want to and am planning for. You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week.

For $9/month you also get the second half of the weekly Goodie Bag post, plus a weekly paywalled in-depth article on this great sacred patrimony, plus our Benedictine Book Club in the Substack Chat. There are also occasional extras like downloadable exclusive high resolution printable images, ebooks, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts.

If you would prefer to set up a recurring donation in an amount of your choice, or make a one-off contribution, you can do that at my studio blog. Of course, anyone setting up a monthly patronage for US $9/month or more will get a complimentary subscription to the paid section here.

This helps me a lot because the patronages through the studio blog are not subject to the 10% Substack fee:

This is the site where I post photos of my own work as it develops. I have a shop there where some of my drawings and paintings are available for sale as prints, as well as some other items.

I thought I’d feature a little gift item from my shop, a blank notebook printed on the cover with that incredible scene of the Last Judgment with St. Michael weighing the souls of those who rise from the grave. The painting is by the great Gothic Flemish painter, Hans Memling.

Drawing reality; what are “the Canons”?

People ask me quite regularly how they can begin to learn iconography. I usually recommend these instructional drawing vids from a South African iconographer, Julia Hayes. Hers were the first iconography tutorial series I paid money to sign up for, and I still support her and use her material from Patreon.

Another online instructor I recommend is Antonis Kosmadakis, a Cretan Greek iconographer who also does very good straightforward videos giving the details of how it’s done. Both have Patreon and pages on Facebook as well, and I’ve found they readily respond to questions.

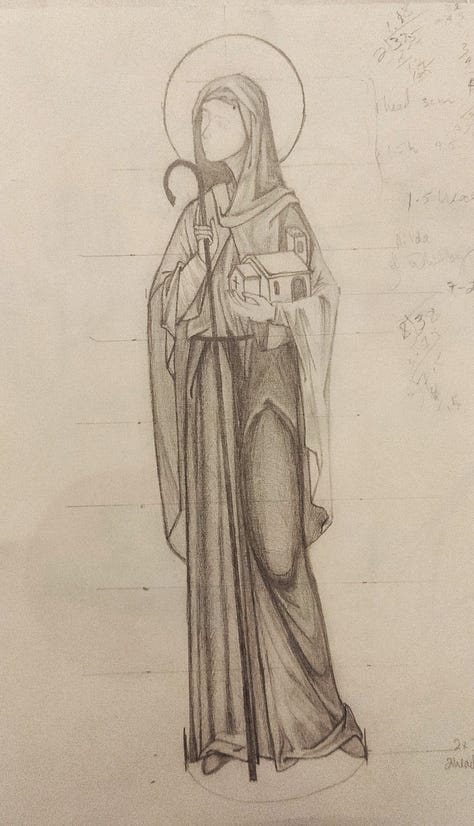

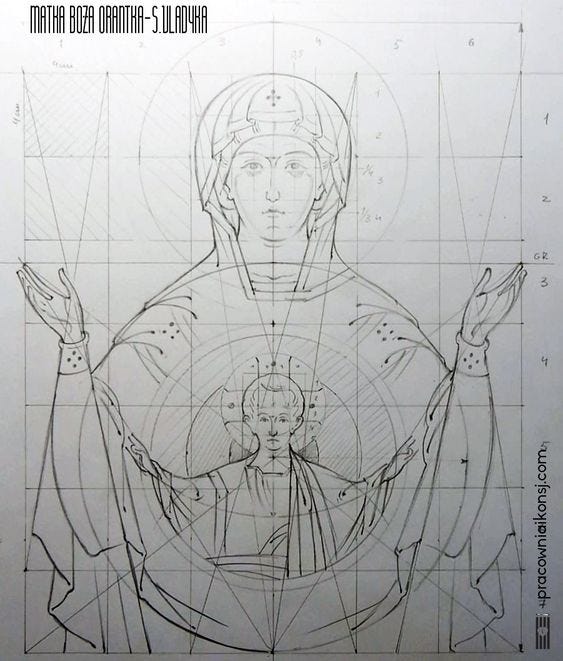

Both these iconographers teach the classical style, including how to draw according to the Byzantine (Greek) canons.

How is it possible to have a mathematical formula for drawing people? Well, here’s one of those little secrets of the universe you hear about: we may not all be the same, but we’re all kind of the same.

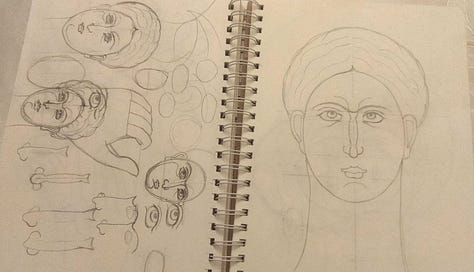

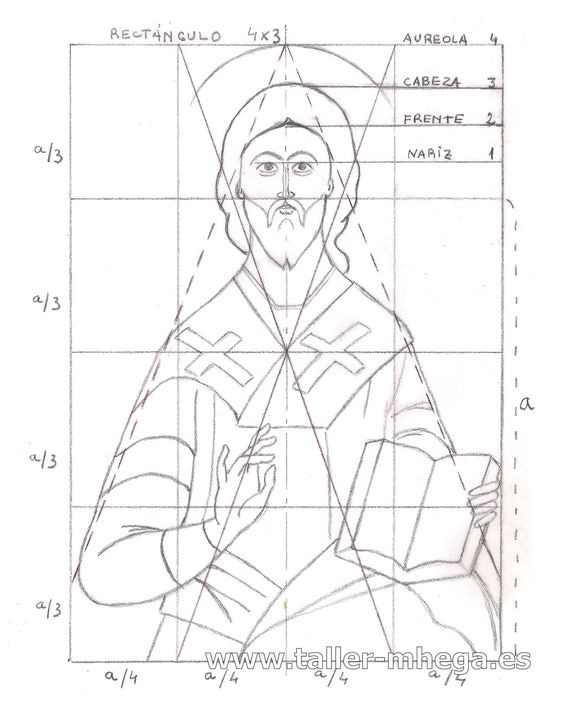

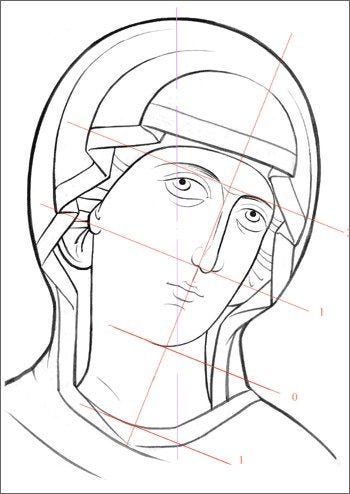

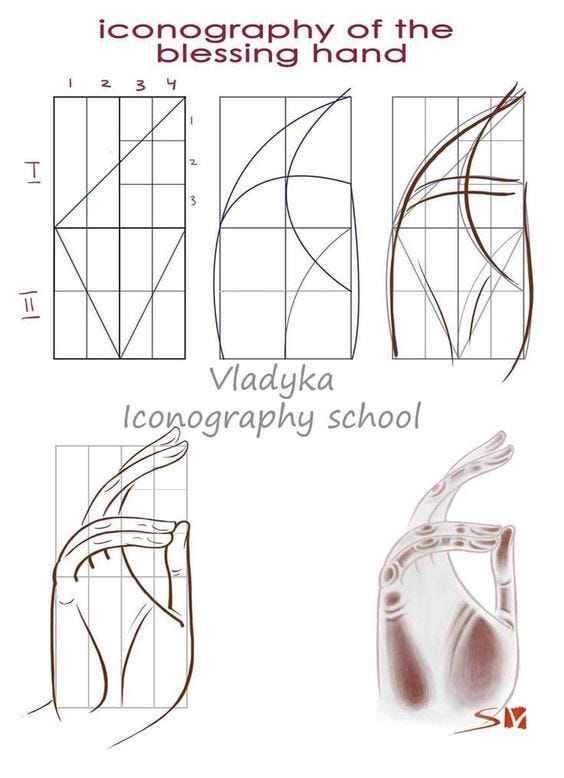

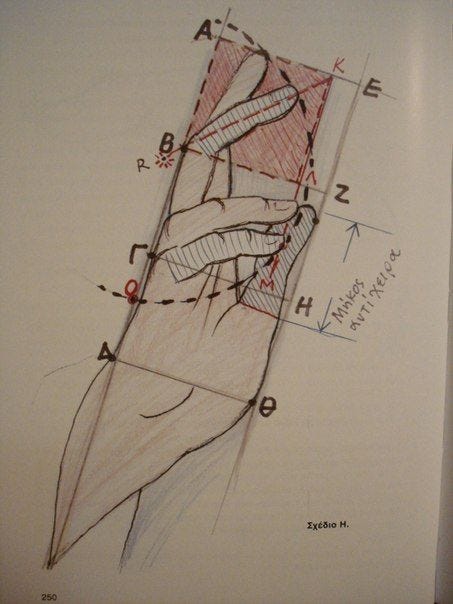

This was how I started, after doing 4 years of observational drawing training in the old European Academic model; by learning the “canons” which are the foundation of Byzantine, iconographic painting. My sketchbook is full of bad drawings of Byzantine faces, eyes, noses, hands and feet, maps of the figure according to the canons.

If you want to learn to draw icons properly the method isn't really difficult to get down, because it's so systematised. It takes a long time to really perfect the whole art of creating a painted icon in the traditional method, but the basic framework of the drawing isn't difficult to learn. It’s a formula. After you’ve got it in your head, it’s just a matter of practice.

How is it possible to have a mathematical formula for drawing people? Well, here’s one of those little secrets of the universe you hear about: we may not all be the same, but we’re all kind of the same.

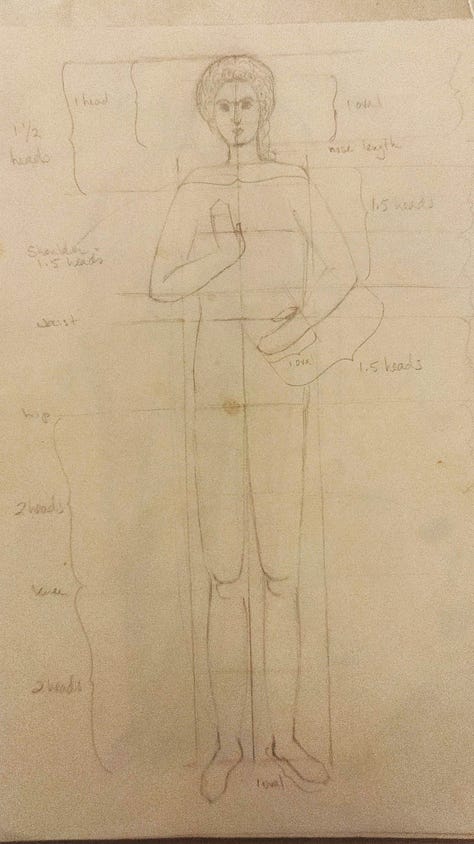

When we talk about a “canon” what we mean is a “rule,” a system for approaching a goal to produce a standard result1. So a proportional canon for drawing the human figure tells us that it is possible to create a “map” of humans that more or less fits everyone - the ideal or standard human figure.

You’re about seven heads high - or so

You’ve probably seen those drawings of the “ideal” human figure being 7 or 8 “heads” tall…2

The idea that there is an “ideal” or perfect set of proportions for a human was written about by Greeks, and the concept of “proportionality” became enshrined in western art through its use by Greek sculptors and their Roman imitators. The basic gist is that every measured length of the human form is related somehow to all the other ones. We are indeed, “fearfully and wonderfully made…” according to a clear set of design parameters.3

This idea doesn’t come from ancient Greece, it was just written down in Greek for the first time - we think - by Polykleitos, so the Greeks have claimed it. But really it’s one of those very ancient bits of human knowledge the origin of which is lost to history. You can see it being used in nearly all public art since we started doing civilisation, including Egypt and old Babylon4. Artists figured out and wrote down systems of canonical proportions in India, China and Japan. Because humans are all more or less the same everywhere.

And the “seven heads high” part is just the beginning. By the time we had got as far as Byzantine sacred art, we’d got a pretty reliable map of nearly every detail of the human form and we knew how every bit related in size to every other bit. And that is one of the main reasons Byzantine icons all look more or less the same, and are not “naturalistic” in the sense we often prize today, but mathematically perfect, ideal.

And in “classical” Byzantine iconography, we have a formula or standard canon for every feature.

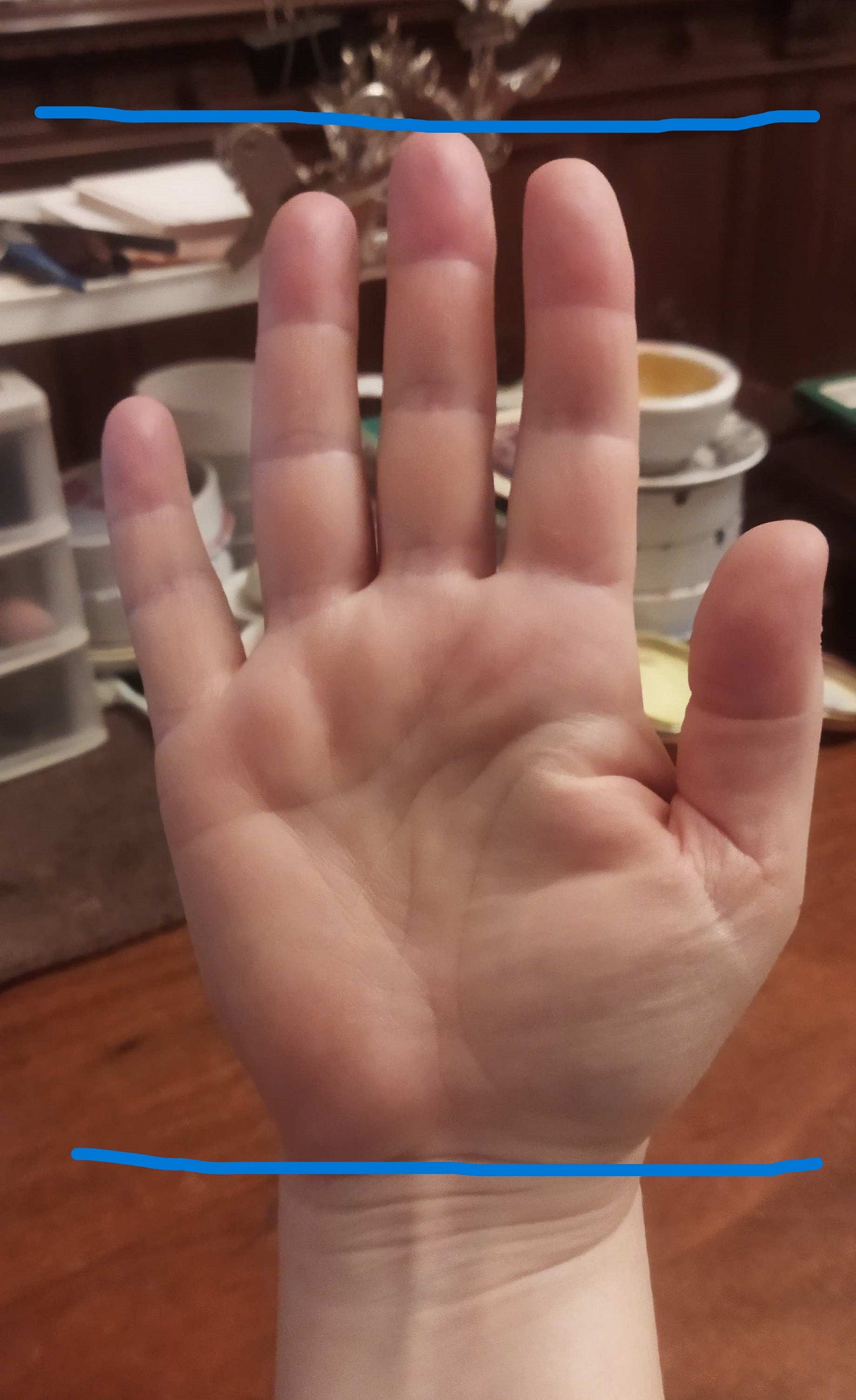

I learned when studying this that every measurement of a Byzantine icon is based on the length of the nose. The face is three noses from the bottom of the chin to the hairline, and one more to the top of the head when the head is facing forward. Then you have both the length of the face and the length of the head, the length of the hand, the distance from the elbow to wrist… all based on the same starting measurement. Your middle finger is about the same length as the tip of your nose to the point between your eyebrows. That is the same as the length of your palm - so the hand without the wrist is about two middle-fingers (or noses) long. The length of your arm from the tip of your middle finger to the point of the elbow is three hand-lengths5.

There are different canons depending on the style of iconography, but the basic rule remains no matter what style you’re learning. Everything is measured with minute care; the width of the nostrils, the distance between the pupils, the length of the mouth, the distance between the top lip and the bottom of the nose, the length of the fingers in relation to the hand, the width of hips and shoulders, the length of the neck… And all are interrelated, so the finished figure “makes sense” and coheres visually.

Of course, we Moderns have been trained all our lives to value "originality" and use "formulaic" as a negative criticism, but in Byzantine art the whole value system is very different. While it's NOT true that all Byzz icons must look identical - there is certainly room for individuality and artistry within the framework - the images do have to be recognisable.

Iconography is about Christian prayer, a desire to connect in real life to the real heavenly person. The image has to be identifiable by everyone who looks at it as that particular person being addressed in prayer, and never mistaken for someone else. And that is why, as I’ve talked about before, we use the canons and don’t do “individuality” in the faces, and we certainly don’t ever use live models; this isn’t portraiture in the modern sense of a “photographic” or naturalistic likeness. It’s hagiography.

We’re all built pretty much the same

You can try it right now: place the bottom edge of the heel of your hand on your chin. The point of your middle finger should almost be at your hairline. Since everyone is different, and no one perfectly fits the ideal canonical proportions, your finger might be a little longer or shorter, or your chin lower in relation to your hairline, but it’s going to be more or less there. I have somewhat stubby fingers and quite a pointy chin, so I have to do a bit of stretching.

These proportional measurements are so reliable that you can actually construct a pretty plausible looking figure drawing entirely without a model. Just make sure all the measurements are proportional. Art students used to be taught this skill as a normal part of their course.

This is the other method of figure drawing, the one I didn’t study in my atelier course, but is still used as a normal part of the academic drawing curriculum at many private ateliers in the revival. In the contemporary fine art and illustration worlds, these techniques are called “constructivist” drawing and “comparative measuring.”

The advantage of it is immediately obvious; you can draw straight out of your head, no need for models or reference photos. And if you’ve already learned observational drawing techniques, you’re an unstoppable drawing-machine, a superhero with powers people will think are magical.

But it only works because humans really are all built according to a standard mathematical model. There are a number of different canons that will give you slightly different styles of figure drawing. The Greek canon, the one used most often by the Byzantine painters, is 7 or 8 heads. Others give six or six and a half. But the principle remains the same; humans are mappable6.

.

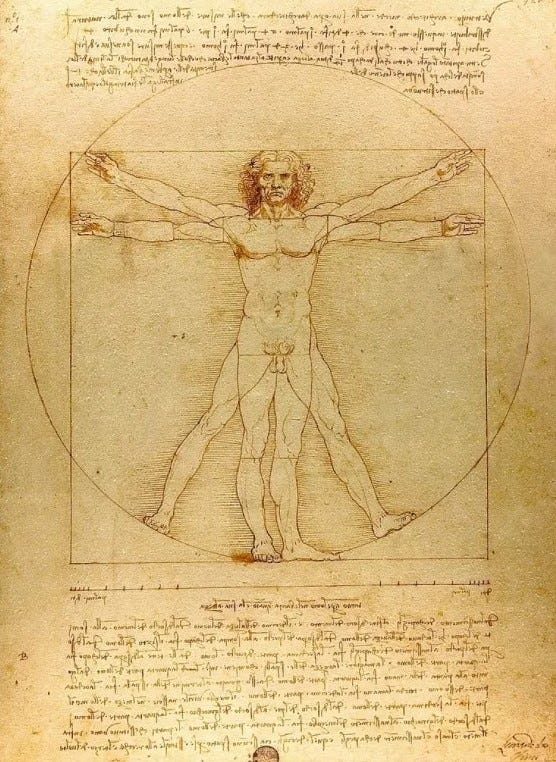

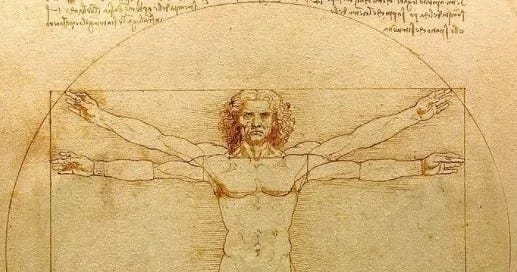

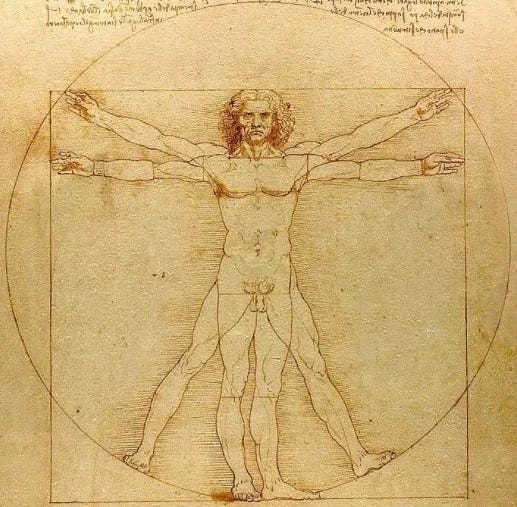

Leonardo’s Canon

Let’s take another look at good old Vitruvian man, with Leonardo’s own commentary - the translation of the handwritten text that goes with the drawing - and see if it makes some sense. He didn’t bother himself over noses but took everything from the internal proportionality of the figure based on its full height.

We’ll put it in point form so it’s easier to figure out. See if you can follow along:

The length of the outspread arms is equal to the height of a man.

From the hairline to the bottom of the chin is one-tenth of the height of a man.

From below the chin to the top of the head is one-eighth of the height of a man7.

From above the chest [centre of the collarbone] to the top of the head is one-sixth of the height of a man.

From above the chest to the hairline is one-seventh of the height of a man.

The maximum width of the shoulders is a quarter of the height of a man.

From the breasts to the top of the head is a quarter of the height of a man.

The distance from the elbow to the tip of the hand is a quarter of the height of a man.

The distance from the elbow to the armpit is one-eighth of the height of a man.

The length of the hand is one-tenth of the height of a man.

The hip line is at half the height of a man;

The foot is one-seventh of the height of a man.

From below the foot to below the knee is a quarter of the height of a man.

From below the knee to the hip line is a quarter of the height of a man.

The distances from below the chin to the nose and the eyebrows and the hairline are equal to the ears and to one-third of the face.

The universe makes sense

It’s a pity that children are not taught this basic method of drawing. It’s not really difficult, and the basics could be taught to quite young children very easily. As a methodology it's useful to do these exercises to improve any kind of drawing, to train the eye to analyse any subject from a structural viewpoint - how is the thing you're looking at constructed? What does it look like broken down to its "skeleton" of lines, shapes, angles, shadows and highlights, its compositional framework?

You can apply this principle, of breaking down a subject into its basic shapes and forms, not only to iconographic drawing, but to drawing anything. Even if you can only draw stick figures now, you can get to the stage of doodling icons really fast, and it's incredibly satisfying and relaxing as a hobby.

One of the things that it might do if it were taught, would be to provide a bulwark against certain nonsensical, anti-human trends in philosophy - and their concomitant lovecraftian social fads. It is one of the deep foundational ideas of the old Christian social order; there’s a system, handed to us ultimately from God, that you can learn, for everything in life. The rule of life for monks - the Rule of St. Benedict - tells you how to become a saint. The rule of drawing figures tells you how to depict a human.

All these canons of existence are really only descriptive; they’re derived from observation and the application of universal principles that actually work. Because the universe is constructed with minute care and attention to detail. It all makes sense.

These are for adults; child proportions are a different set of measurements.

Yes, it’s definitely related to Plato and his “forms”. But we don’t need to get into that now.

Whence quite a lot of “Greek” knowledge came.

I know what you’re doing right now. It’s easier with callipers.

Things get really wacky and cosmological when you start connecting the human proportions to the Golden Section, but we’ll save that for later.

Eight heads, same as the classical canon.

Fascinating. I have toyed with copying icons and realised there were principles here at work but to have it elucidated so clearly is marvellous, thank you.

Music--or the overtone series on which most music is based--is also all about ratios. Though interestingly, Western Music is literally out of tune with the overtone series, i.e., with nature. It's *close enough* but if you hear a in-tune major 3rd, for example, vs. one on a piano, the difference is striking. The Western tuning system is a compromise--we trade being in tune for being able to easily modulate to any key. It may be going too far to say that this is a Faustian bargain, but heck, I'll say it anyway.

For those interested in hearing it, here is a minute video of music phenom Jacob Collier demonstrating the difference.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XwRSS7jeo5s

More to the point, a lovely article. Thank you.