Romanesque art: not messing about

At the Sacred Images Project we talk about Christian life, thought, history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of sacred art. The publication is supported by subscriptions, so apart from plugging my shop, there is no advertising or pop-ups. It’s my full time job, and while it’s now providing me with a full time income, we are now looking at growing this into a multi-layered, multi-media project, so I can’t yet provide all the things I want to and am planning for.

You can subscribe for free to get one a week.

For $9/month you also get a second, weekly paywalled in-depth article tracing the history and meaning of our great sacred patrimony. For paid subscribers there are also extra posts with in-person explorations, exclusive photos and videos and materials like downloadable exclusive high resolution printable images. In the works are ebooks, mini-courses, videos and eventually podcasts.

From the shop: This is a little egg tempera painting I did based on a 14th century fresco in one of Narni’s medieval churches. The original is sold, but you can have a high quality art print either on a wood panel, or museum quality paper.

I think it would make an elegant addition to a prayer corner or mantel.

You can order one, and lots of other nice things, at the shop, here:

I was scrolling idly around Pinterest yesterday looking for medieval manuscript miniatures, and thinking about what I was going to do for my next large-scale drawing, and came across this: one of my favourite things, the Nazareth Crusader Capitals…

These beautifully carved, swirling and lively figures almost dancing around these stone capitals were created to adorn the Crusaders’ Basilica of the Annunciation in Nazareth. Only five survive, carved in the late 12th century in local white limestone, and are regarded as one of the greatest treasures of Romanesque art.

We’ll get back to these…

And I remembered that I’ve been meaning for some time to do a post on Romanesque art in general.

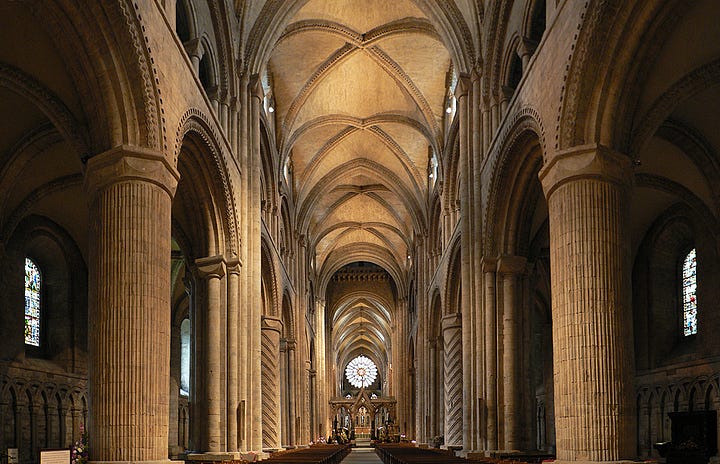

Part 1: Architecture - “THICC” and built to last

You might have heard the term Romanesque in passing. Academic art historians tend to give it pretty short shrift: it’s mostly relegated to one of their dismissive categories, a “transitional period,” between Byzantine and Gothic. Romanesque - a term coined by 19th century French art historians1 is so called because, especially in architecture, it was a conscious revival of some old Roman Imperial ideas, particularly round arches, barrel vaults and monumental stone construction.

It emerged in the late 10th century and lasted until the 12th century. The conquest of Anglo-Saxon England by William Duke of Normandy was the start of an architectural flowering of English Romanesque that would come to be known as Norman.

When William overthrew the Saxon kingdoms and duchies of the island, he wanted everyone to know he was there to stay. He set about a brutal programme of subjugation of his newly conquered people, including building a large number of castles and stone churches and monasteries according to continental trends. Such large scale, monumental, stone construction was rare in England before 1066, and had not been at the centre of English life since the exit of the Roman Legions in the early 5th century.

Very little even of traces and memories of England’s Saxon architecture remains; but everyone knows what William did and quite a lot of his material works and those of his successors are still in use.

In England the best and most enduring examples of Romanesque Norman architecture is mostly in the churches and cathedrals (many of which are ecclesiastically only cathedrals - seats of bishops - because they were so-designated after the Dissolution of the Monasteries for the apostatising Church of England).

It was the first pan-European style since the fall of the Roman Empire, and is characterized by its use of semi-circular arches, thick walls, and massive forms.

Here’s a quick little bullet point list of things to look for in Romanesque architecture:

Semi-circular arches: Romanesque arches are rounded, rather than pointed like Gothic arches. This type of arch is stronger and more stable, making it ideal for supporting the weight of large buildings.

Thick walls: Romanesque buildings often have thick walls, which provide support and insulation. The walls may also be decorated with arcades, columns, and other architectural elements.

Massive forms: Romanesque buildings are often large and imposing, with a sense of solidity and strength.

Solid geometric decorative forms: Repeating geometric motifs. Zig-zag, chevrons, carved cables. Animal and plants stylised into geometric forms.

What’s the message? “I’m here to stay, Saxon peasant. Better get used to it.” This was the start of what can properly be called the English Middle Ages.

Part 2: Painting - geometric and heavily stylised, bold colours and generally in-your-face

More tomorrow…

I wanted to take a moment to thank those who have ordered prints of my work, cards and Christmas ornaments from my online shop since I launched just a few days ago. You can find my own work as well as items made from original medieval images, part of my “Hilary’s Sources” line. I hope those who ordered will enjoy the things they bought for many years.

If you’d like to take a look at my work, follow my studio blog or make a one-off or even monthly contribution, click here:

If you’d like to see what’s on offer at the shop:

The story goes that French historian and archaeologist, Charles de Gerville, wrote a letter to his colleague, August Le Prévost, using the term romane to describe the architecture spanning from the 400s to 1200s. He didn’t think much of it, calling it “debased Roman architecture” comparing it to the Romance languages that were “degenerated Latin language”.

Thanks. Romanesque is my favorite.