In this post for free subscribers we’ll start to take a look at the medieval book, manuscripts, that were often richly illustrated and cost more than your house.

The world of manuscript art is a fascinating blend of devotion, artistry, craftsmanship and scholarship that flourished across medieval Europe from the Carolingian Renaissance to the invention of the printing press, between the 6th and 16th centuries. These manuscripts are not just texts; they are vibrant visual masterpieces that provide a window into the medieval mind and its intricate interplay of faith, culture, and artistic expression.

This post is free to all subscribers and readers.

The Sacred Images Project looks at art history and culture through the lens of the first 1200 years of Christian sacred art.

If you would like to accompany us into a deep dive into these spiritually and culturally enriching issues, to grow in familiarity with these inestimably precious treasures, I hope you’ll consider taking out a paid membership, so I can continue doing the work and expanding it.

This is my full time work, but it is not yet generating a full time income. I rely upon subscriptions and patronages from readers like yourself to pay bills and keep body and soul together.

You can subscribe for free to get one and a half posts a week. For $9/month you also get a weekly in-depth article on this great sacred patrimony, plus extras like downloadable high res images, photos, videos and podcasts (in the works), as well as voiceovers of the articles, so you can cut back on screen time.

We are significantly further ahead in the effort to raise the percentage of paid to free subscribers than we were a month ago, from barely 2% to just over 4.2%, but this is still well below the standard on Substack for a sustainable 5-10%.

The other way you can help support the work is by signing up for a patronage through my studio site, where you can choose for yourself the amount you contribute. Anyone contributing $9/month or more there will (obviously) receive a complimentary paid membership here.

You can also take a scroll around my online shop where you can purchase prints of my drawings and paintings and other items.

Like this St. Michael the Archangel notebook, printed with an image from Hans Memling’s great Last Judgment painting.

And now, back to our show…

I don’t know if anyone has done a lot of hand sewing of clothes, but I used to and am kind of getting into it again lately. If you have, or have done any other painstaking and exacting handcraft, you will know how time slows down while you’re doing it and your brain calms and you achieve a kind of mentally suspended state. And it sort of just makes sense that if you’re doing this dress by hand anyway, you might as well go the whole way and do hand bound button holes or a little embroidery around the cuffs - the extra time it will take to make it extra nice seems irrelevant.

I think if you do this sort of work, you can get a glimpse of the kind of mindset that went into making an illuminated manuscript. It had to be as good as they could possibly make it, and the time involved, so important to us moderns, just wasn’t a factor. Factory time hadn’t even been imagined yet, and the time a book took to create, intended as it was for all the ages, didn’t matter.

Manu scriptus: ‘written by hand’

Creating a medieval manuscript was a slow, painstaking and labour-intensive process that required the combined efforts of many skilled craftsmen. The finished object was intended to last and was often commissioned to contain beautiful artwork intended to transport the reader beyond this material world. So it had to be good.

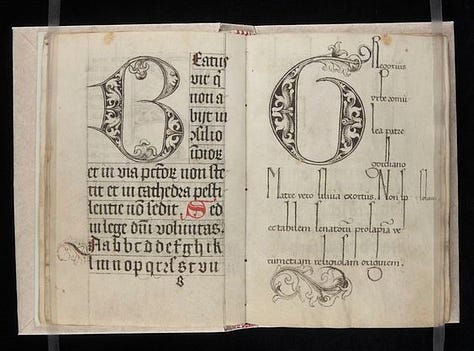

Preparing parchment, treated skins of animals like calves, sheep, or goats, involved cleaning, stretching and scraping the skins to achieve a smooth, durable writing surface. When the parchment was ready, each page was measured and cut to size. Scribes would carefully plan the layout of the text, often using a lead point to rule lines as guides for writing.

Scribes made their own materials, including pens made from goose feathers, which they trimmed to a fine sharp edge to create a consistent line. They prepared their own ink from natural sources such as oak galls, and wrote in a steady, measured hand to avoid mistakes. Errors were difficult to correct - you scraped away a layer of the parchment with a penknife - so perfection was paramount, requiring hours of focused work for even a single page of text.

In the case of an expensive commissioned book like the Gospels or the Psalms or other liturgical books, the next step was to turn the book into a work of art. Using finely ground pigments mixed with binders like egg white or gum Arabic, they created the illustrations that have become so renowned and treasured down to our own time.

What kind of books?

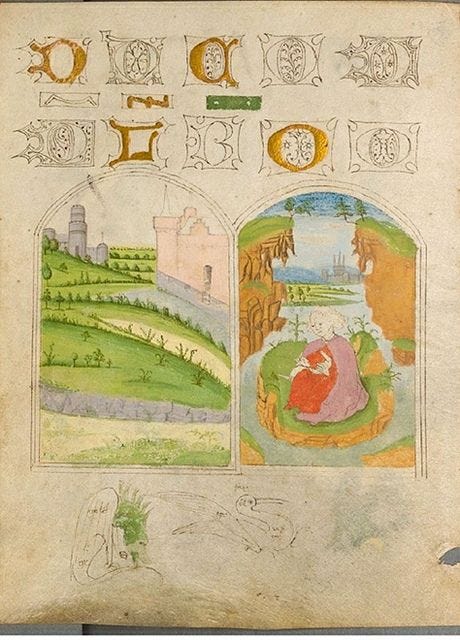

Books of hours, a book of daily devotions, prayers and psalms, to help people practice their spiritual lives at home, are probably the most common type of richly illuminated manuscripts that have survived. They were produced from the earliest times until the end of the manuscript period with the invention of the printing press and even beyond. The “hours” refers to the so-called canonical hours - Matins, Lauds, Prime, Terce, Sext, None, Vespers and Compline - which mark the fixed time of prayers during the day in a monastery and which came to mark the passage of the days throughout the Christian world.

In traditional monastic life certain sets of Psalms, biblical readings and commentaries by Fathers and Doctors of the Church are prescribed for recitation or chanting at each of the Hours, in a great cycle throughout the liturgical year, and the monks’ breviaries kept track of it all.1 A book of hours is a version of the breviary suited to devout laity, often noblewomen and the wives of gentry, who could afford them. And many survive particularly because they were treasured objects that cost a great deal to commission, with rich illustrations and gold leaf decoration.

Other kinds of books produced by medieval scribes included, of course, Bibles and liturgical books, missals, breviaries and sacramentaries. Also common were commentaries on Scripture and other theological works and the lives of saints.

But it wasn’t all religion then any more than it is now and there was demand for secular subjects. Book manufacturers produced surviving works by Greek and Roman philosophers, historians, and playwrights, translations and compilations of scientific and philosophical knowledge from the ancient world and Islamic scholars. Laws, chronicles, and historical accounts and even poetry and entertainment.

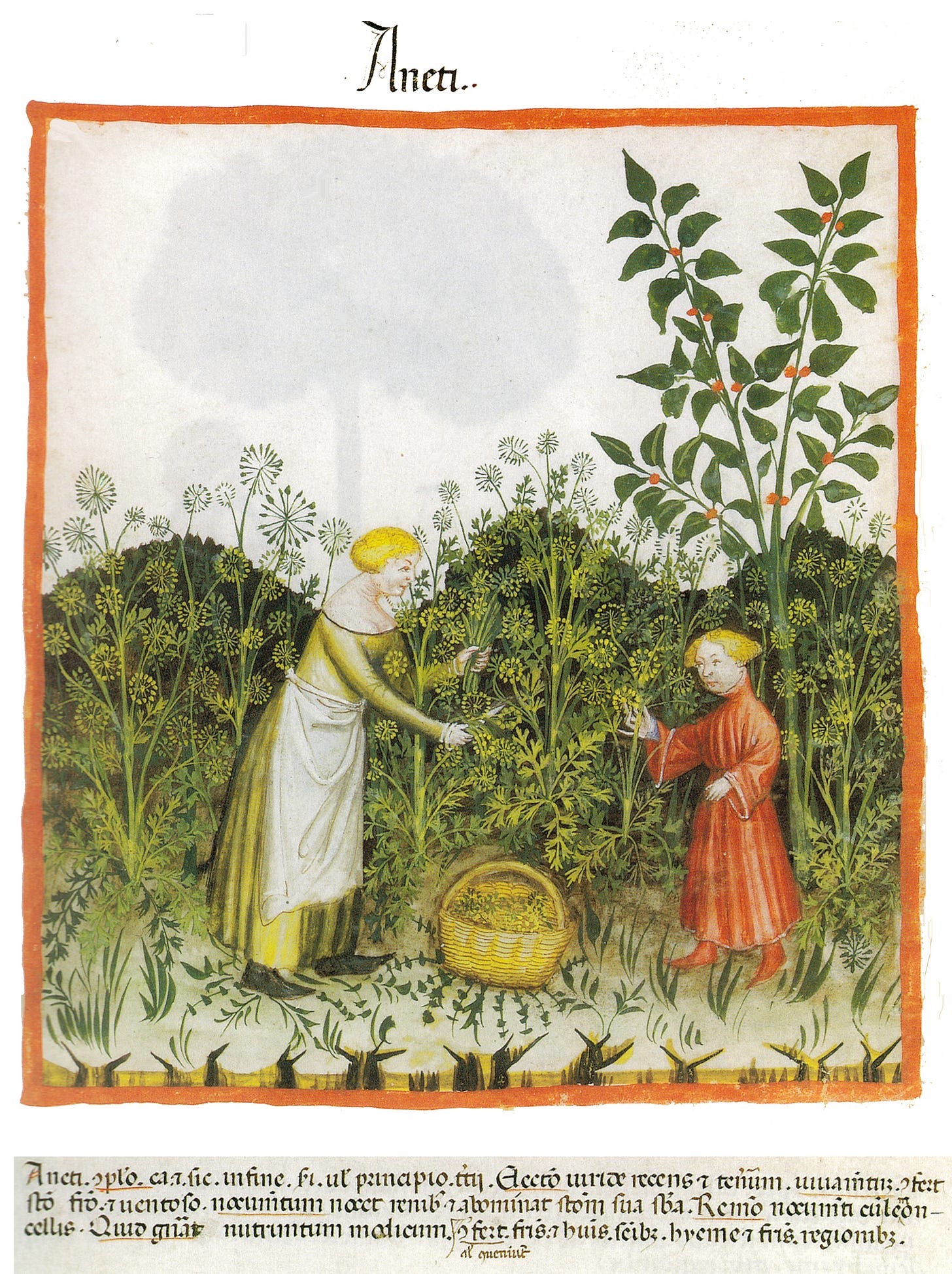

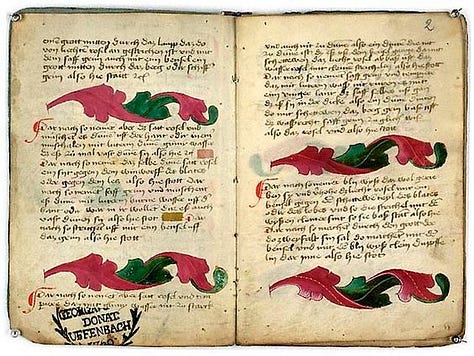

As universities grew in prominence, scribes produced scholarly works on all subjects studied and even lecture note compiled by university students. For everyday use, scribes might copy herbals, books on medicinal plants and their uses, cookbooks and guides on gardening, health and wellbeing and even guides for new housewives on household and estate managing.

Not only monks

While we have a rather romantic idea of monastic scribes, as urbanisation increased and literacy became more generally common (due largely to monastic schools) book manufacturing was to become increasingly undertaken by lay businesses. Very often a particularly beautiful manuscript that survives comes to us “from the workshop” of a particular scribe. This is true especially in later times, as education spread beyond monasteries and into universities and cities, and the demand for books grew. Monasteries alone couldn't keep up.

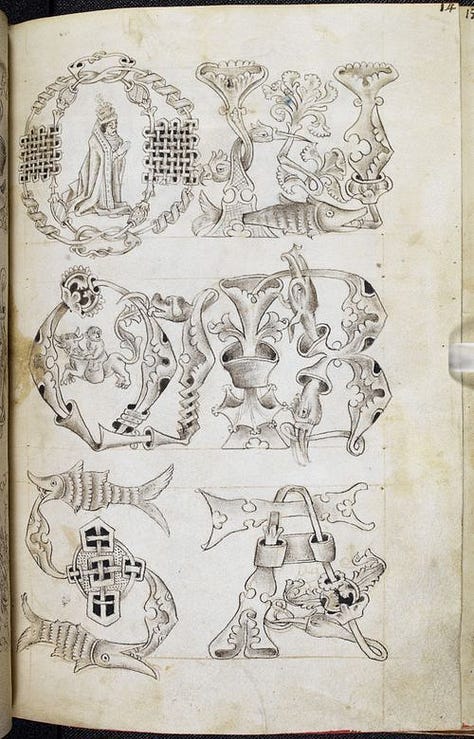

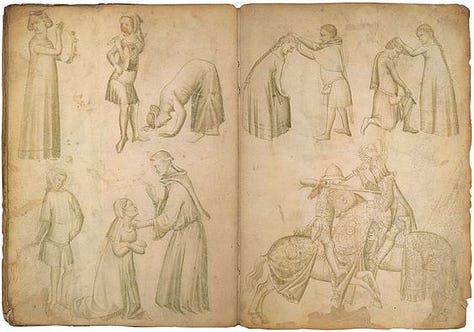

In these workshops a few highly skilled scribes and their apprentices would work on parchment produced in another shop and bought in bulk. Illuminators would often work from model books of sketches or illustrations that sometimes became copied and standardised across national boundaries.

With the growth of towns and cities, a new class of wealthy patrons emerged – merchants, nobles, and even some educated professionals – who could afford to commission books. The rise of universities created a need for a wider variety of secular texts, like legal documents, scientific treatises, and classical works. Lay businesses were more flexible in meeting these specific needs compared to monasteries with their focus on religious texts.

OK, let’s look at the art.

The art of the Christian islands

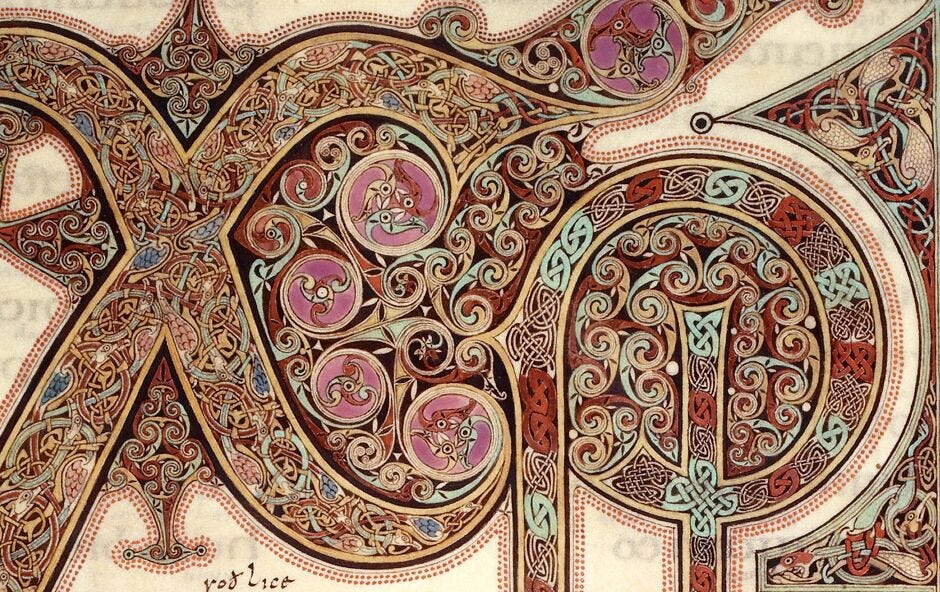

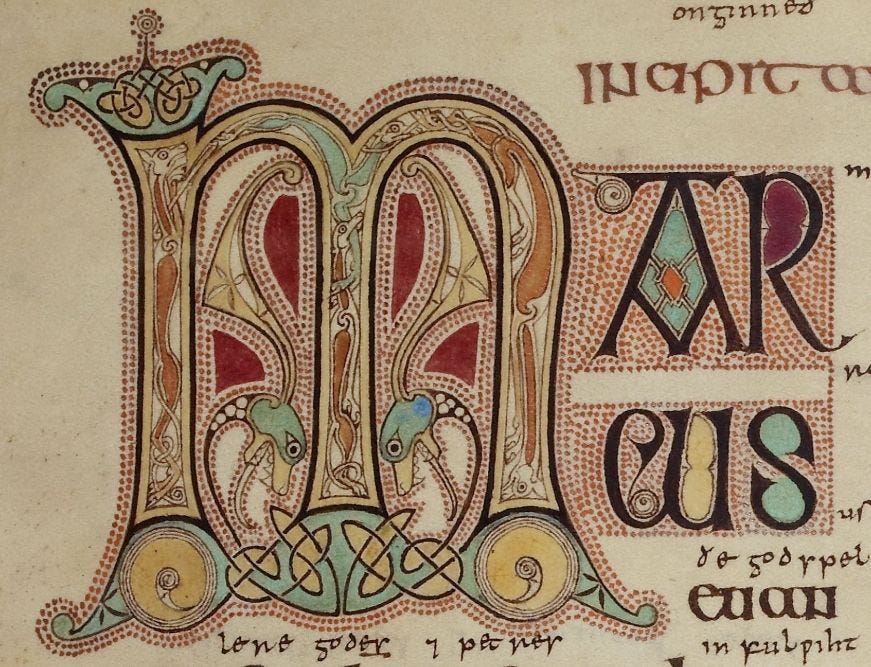

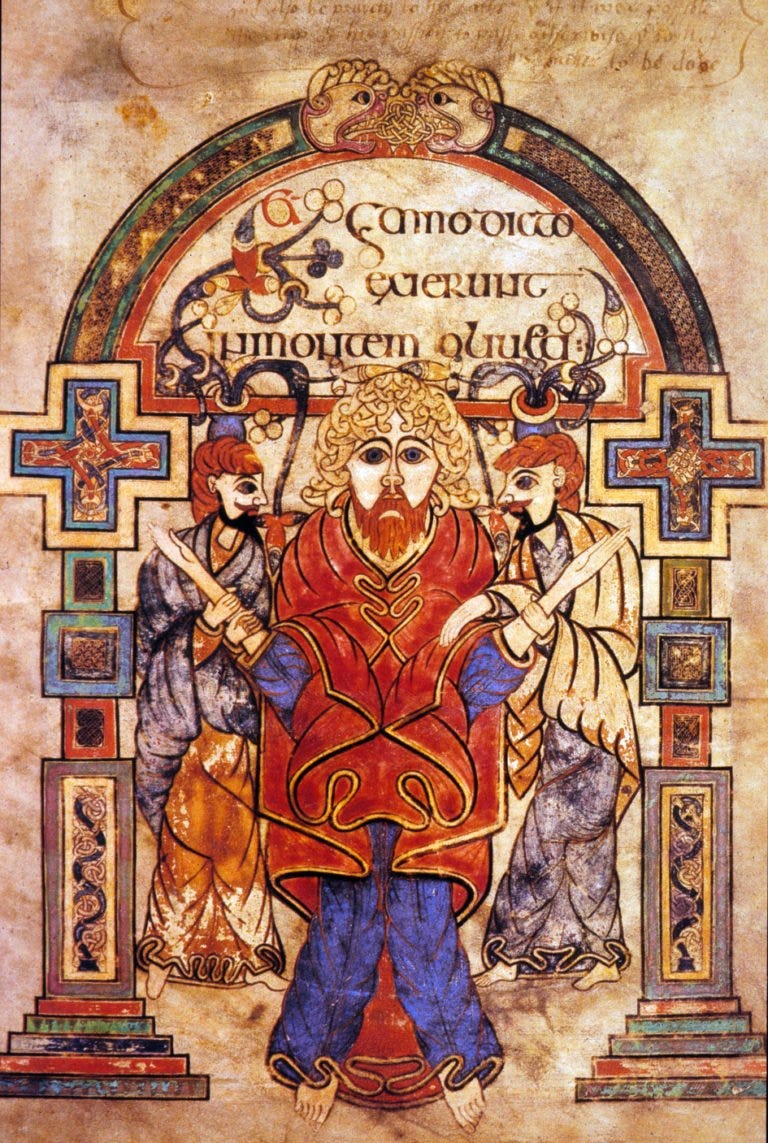

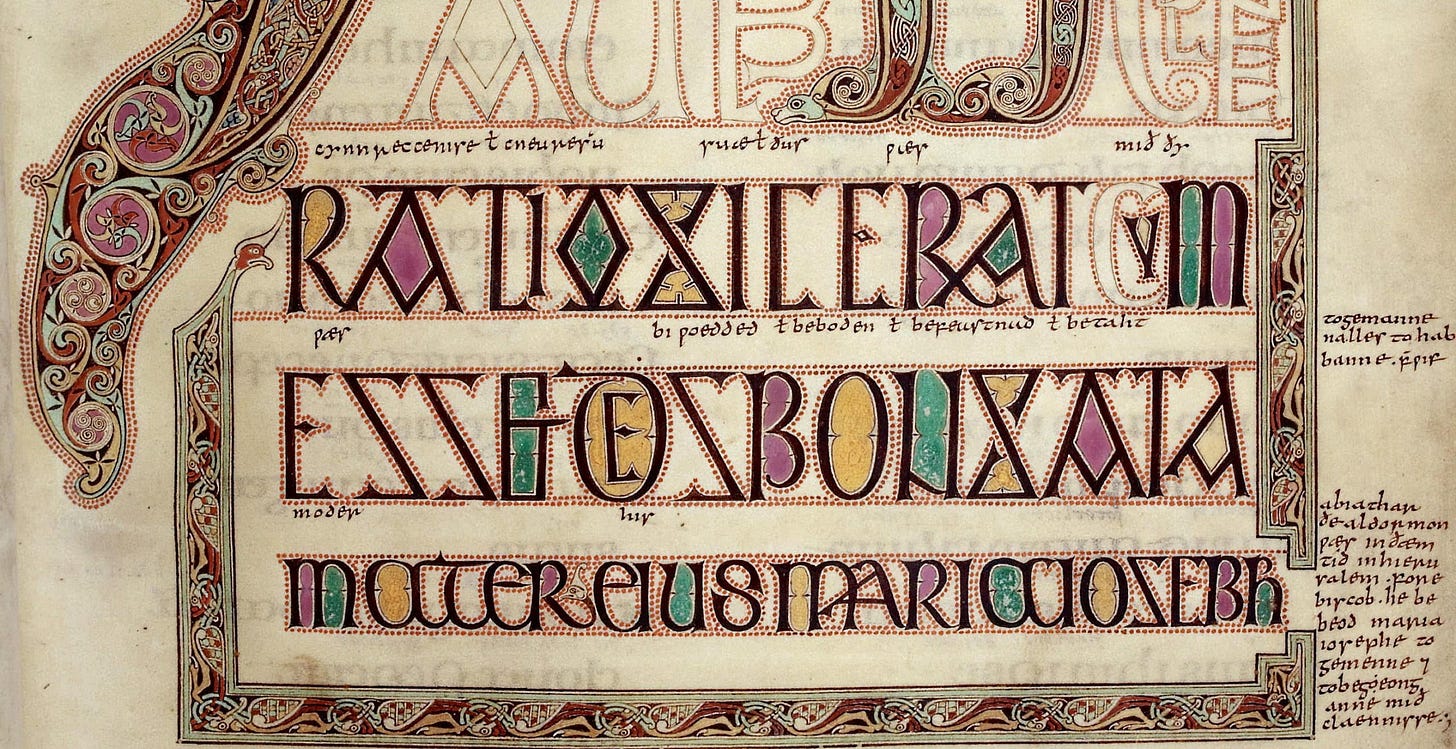

The story of manuscript art begins with the Hiberno-Insular tradition, flourishing in the British Isles from the 6th to the 9th centuries. This period produced masterpieces such as the Book of Kells and the Lindisfarne Gospels, renowned for their vibrant interlace patterns, zoomorphic designs, and intricate initials.

Hiberno-Insular manuscript art emerged from a blend of early Mediterranean (Carolingian) styles and native Celtic artistic elements, creating a new visual language. The emphasis was much more on decoration than illustration of narratives.

The most characteristic element was interlace, a complex web of mathematically derived interwoven lines, knots and spirals. These were incorporated highly stylised zoomorphic figures: animals, real and fantastical. These manuscripts are also known for their rich and often contrasting colours, adding vibrancy to the intricate decorations.

Human and animal figures were often depicted as completely stylized and abstract with little trace of anything naturalistic. The focus was on creating a sense of rhythm and movement within the decorative scheme.

Lindsisfarne Gospels:

It’s remarkable that such incredible works were created at a time of devastating invasions and huge political and social upheavals as a post-Roman Britain contended with the long-term political, social and economic after effects of the imperial retreat. Monks would have read from this book during the Mass and Divine Office at their Lindisfarne Priory on Holy Island. This is the monastic community that held the shrine of the great St. Cuthbert who died in 687.

It was illustrated in the 8th century on the Holy Isle by the monastic scriptorium there, led by a Northumbrian monk who was very likely later the bishop Eadfrith. It is made up of two-hundred and fifty-nine leaves and includes full-page portraits of each of the four evangelists, as was to become normal in Gospel manuscripts. It features the famous, highly ornamental “cross-carpet” pages; cross set against a background of intricate ornamentation.

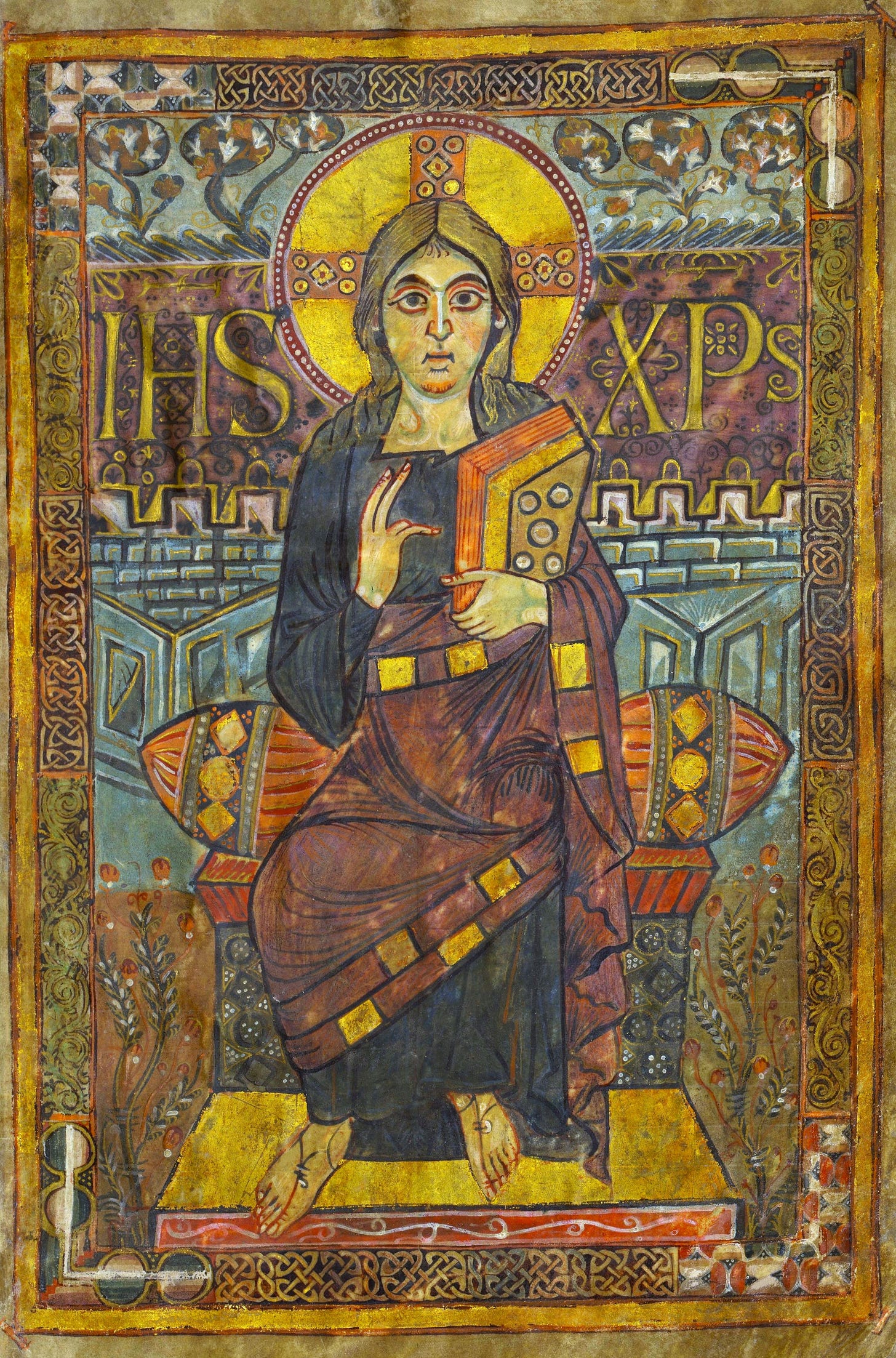

Carolingian: where it all started

As we transition to the Carolingian Renaissance in the 8th and 9th centuries on the continent, we witness an attempt at a revival of the social, political and cultural order of classical antiquity under Charlemagne, the first western emperor after Constantine removed to Byzantium. Carolingian manuscripts show a sophisticated blend of classical Roman styles and Christian iconography.

Monasteries, often founded under imperial charters by Charlemagne, became centres of cultural revival, where monks dedicated themselves to copying and illuminating texts with a renewed vigour. This era laid the groundwork for subsequent developments in manuscript art, emphasizing both the continuation of classical traditions and the introduction of innovative artistic expressions.2

The Godescalc Evangelistary is a masterpiece of the Carolingian Renaissance. Commissioned by Charlemagne himself, it is one of the earliest examples of Carolingian art. It was created in the court school at Charlemagne’s capital of Aachen. An evangelistary contains the readings from the Gospels used in the Mass throughout the liturgical year.

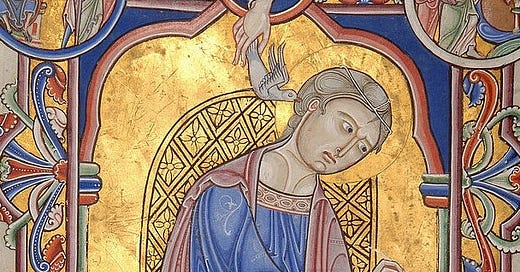

The manuscript is notable for its lavish illuminations, in a blend of classical Roman/Byzantine elements, such as acanthus leaves and realistic human figures, combined with intricate interlace patterns and vibrant colours characteristic of Insular art.

Romanesque

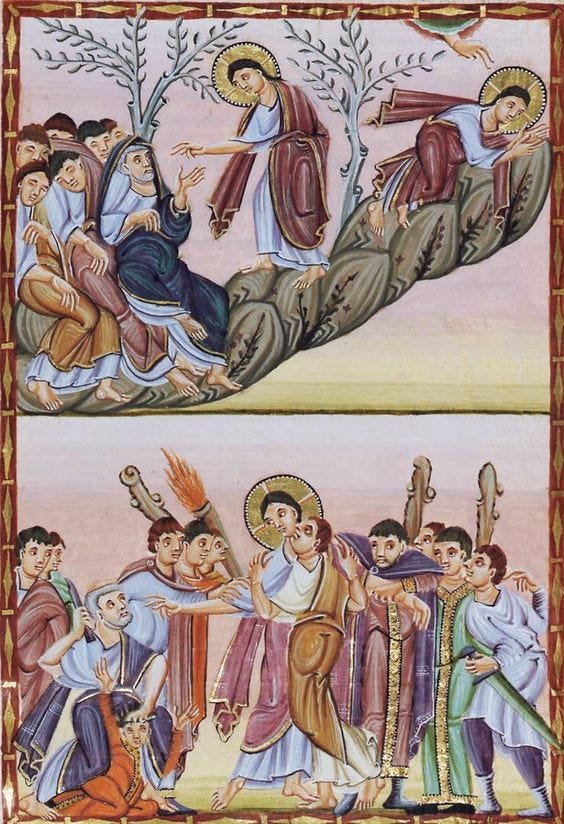

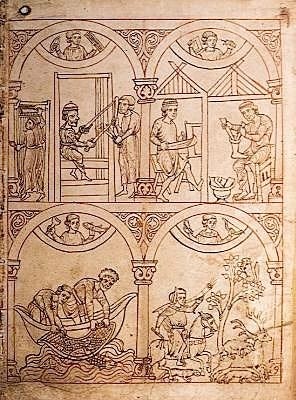

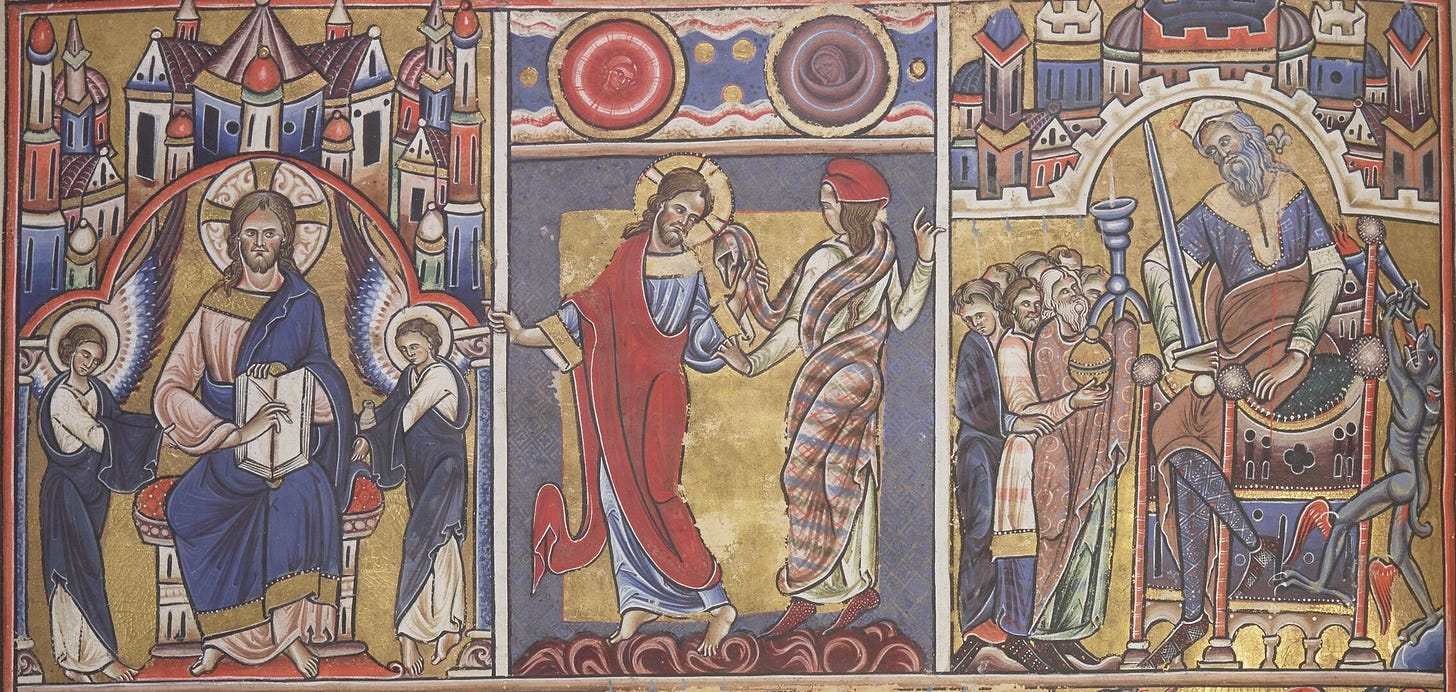

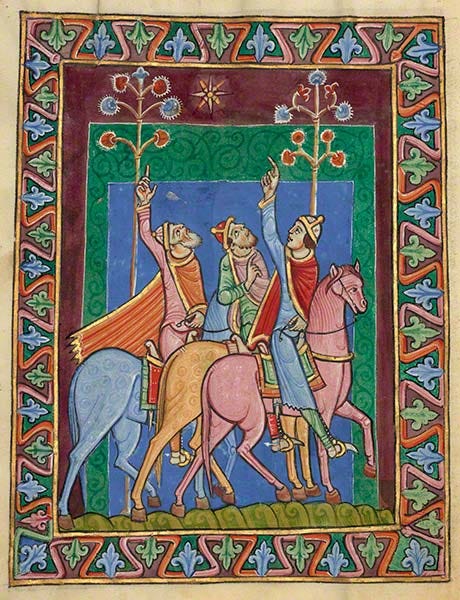

As we’ve discussed, the Romanesque period from the 11th to 13th centuries introduced bold, colourful manuscripts with strong outlines, exuberant patterns and highly stylised zoomorphic and human figures.

Romanesque painting: Heaven in the room with you

This is not Christianity safely away over there, up above the altar. It’s not God up there and far away and not very relevant. This is the entire heavenly court, all of Salvation History crowded into the room with you and looking straight at you. These aren’t images in a movie to be gazed at “reverently” from a safe distance; this is “full immersion” Christianity at its height.

The manuscripts of the Romanesque often incorporated architectural elements and intricate, detailed linear patterns, emphasising storytelling through vivid illustrations. There is still a stylistic connection with the Byzantine, but this is a definitively western form.

The perspective is flat, with little or no landscapes, but not “reversed” as in the Byzantine style. The colours are not graded, but painted in solid blocks outlined by linear patterns outlining the forms. The forms of the body and drapery are shown as reduced to geometric simplification. All the elements are stylised and symbolic rather than representationally natural.

The St. Albans Psalter is an exemplary work from this period. Created in St. Albans Abbey, England, sometime between 1123 and 1143.

It is considered one of the most significant examples of English Romanesque book production, with over 40 full-page miniatures and richly decorated initials.

We’re going to have to stop there and pick up where we left off, the Gothic, next week.

One of the fun-facts of monastic life in the middle ages was that a new monk was taught to recite the entire Psalter - all 150 Psalms - from memory, as his initial training, often when he was still very young. Constant daily repetition of the Psalms and prayers of the Breviary through the annual liturgical cycle is considered to be the main means of sanctification in monastic life. When you think of a monk as “praying always” it is because of this; his mind is filled every hour of every day with the words of the Psalms, as you and I might have a song “stuck in our head”. And this was the meat of his mental life that led to his elevation through the stages of contemplative prayer.

The Carolingian revival is so important to the rest of European artistic history we’re going to have to dedicate a whole series of posts to it soon.

Thank you for condensing and compiling all these landmark pieces into one post! Very helpful to artists like myself. Thank you!🙏

Wonderful look at the manuscripts. I cannot imagine the hours involved. It is very interesting to see how the common thematic elements of eastern iconography played out and were reinterpreted in different ways. I have a small King James Gospel book from the 1980s that has many different illuminations on colored plates. I don't often use it in my devotions, but it is lovely to bring out at times - your essays help understand the different illumination types used throughout. I'll have to pull it out again tonight and revisit it.

Minor correction: "As we transition to the Carolingian Renaissance in the 8th and 9th centuries on the continent, we witness an attempt at a revival of the social, political and cultural order of classical antiquity under Charlemagne, the first western emperor after Constantine removed to Byzantium. "

There were a number of strictly western emperors after Constantine until the last was deposed in 476 (and a few who ruled a unified empire). Charlemagne may have stylized himself as the western emperor reinstated, but the Frankish empire was really very much a new creation with no political or dynastic connection to its namesake.